Stafford Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

51St Annual Meeting March 25-29, 2021 Virtual Conference

51st Annual Meeting March 25-29, 2021 Virtual Conference 1 MAAC Officers and Executive Board PRESIDENT PRESIDENT-ELECT Bernard Means Lauren McMillan Virtual Curation Laboratory and University of Mary Washington School of World Studies Virginia Commonwealth University 1301 College Avenue 313 Shafer Street Fredericksburg, VA 22401 Richmond, VA 23284 [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Dr. Elizabeth Moore, RPA John Mullen State Archaeologist Virginia Department of Historic Resources Thunderbird Archeology, WSSI 2801 Kensington Avenue 5300 Wellington Branch Drive, Suite 100 Richmond, VA 23221 Gainesville, VA 20155 [email protected] [email protected] RECORDING SECRETARY BOARD MEMBER AT LARGE Brian Crane David Mudge Montgomery County Planning Department 8787 Georgia Ave 2021 Old York Road Silver Spring, MD 20910 Burlington, NJ 08016 [email protected] [email protected] BOARD MEMBER AT LARGE/ JOURNAL EDITOR STUDENT COMMITTEE CHAIR Katie Boyle Roger Moeller University of Maryland, College Park Archaeological Services 1554 Crest View Ave PO Box 386 Hagerstown, MD 21740 Bethlehem, CT 06751 [email protected] [email protected] 2 2020 MAAC Student Sponsors The Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference and its Executive Board express their deep appreciation to the following individuals and organizations that generously have supported the undergraduate and graduate students presenting papers at the conference, including those participating in the student paper competition. In -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Vol

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 96, NO. 4, PL. 1 tiutniiimniimwiuiiii Trade Beads Found at Leedstown, Natural Size SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 96. NUMBER 4 INDIAN SITES BELOW THE FALLS OF THE RAPPAHANNOCK, VIRGINIA (With 21 Plates) BY DAVID I. BUSHNELL, JR. (Publication 3441) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SEPTEMBER 15, 1937 ^t)t Boxb (jBaliimore (prttfe DAI.TIMORE. MD., C. S. A. CONTENTS Page Introduction I Discovery of the Rappahannock 2 Acts relating to the Indians passed by the General Assembly during the second half of the seventeenth century 4 Movement of tribes indicated by names on the Augustine Herrman map, 1673 10 Sites of ancient settlements 15 Pissaseck 16 Pottery 21 Soapstone 25 Cache of trade beads 27 Discovery of the beads 30 Kerahocak 35 Nandtanghtacund 36 Portobago Village, 1686 39 Material from site of Nandtanghtacund 42 Pottery 43 Soapstone 50 Above Port Tobago Bay 51 Left bank of the Rappahannock above Port Tobago Bay 52 At mouth of Millbank Creek 55 Checopissowa 56 Taliaferro Mount 57 " Doogs Indian " 58 Opposite the mouth of Hough Creek 60 Cuttatawomen 60 Sockbeck 62 Conclusions suggested by certain specimens 63 . ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES Page 1. Trade beads found at Leedstown (Frontispiece) 2. North over the Rappahannock showing Leedstown and the site of Pissaseck 18 3. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 18 4. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 18 5. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 18 6. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 26 7. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 26 8. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 26 9. I. Specimens from site of Pissaseck. -

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process Within Canada.” Please Read This Form Carefully, and Feel Free to Ask Questions You Might Have

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process within Canada A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Interdisciplinary Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Leo J. Omani © Leo J. Omani, copyright March, 2010. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of the thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis was completed. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain is not to be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis, in whole or part should be addressed to: Graduate Chair, Interdisciplinary Committee Interdisciplinary Studies Program College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan Room C180 Administration Building 105 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A2 i ABSTRACT This ethnographic dissertation study contains a total of six chapters. -

History of Virginia

14 Facts & Photos Profiles of Virginia History of Virginia For thousands of years before the arrival of the English, vari- other native peoples to form the powerful confederacy that con- ous societies of indigenous peoples inhabited the portion of the trolled the area that is now West Virginia until the Shawnee New World later designated by the English as “Virginia.” Ar- Wars (1811-1813). By only 1646, very few Powhatans re- chaeological and historical research by anthropologist Helen C. mained and were policed harshly by the English, no longer Rountree and others has established 3,000 years of settlement even allowed to choose their own leaders. They were organized in much of the Tidewater. Even so, a historical marker dedi- into the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes. They eventually cated in 2015 states that recent archaeological work at dissolved altogether and merged into Colonial society. Pocahontas Island has revealed prehistoric habitation dating to about 6500 BCE. The Piscataway were pushed north on the Potomac River early in their history, coming to be cut off from the rest of their peo- Native Americans ple. While some stayed, others chose to migrate west. Their movements are generally unrecorded in the historical record, As of the 16th Century, what is now the state of Virginia was but they reappear at Fort Detroit in modern-day Michigan by occupied by three main culture groups: the Iroquoian, the East- the end of the 18th century. These Piscataways are said to have ern Siouan and the Algonquian. The tip of the Delmarva Penin- moved to Canada and probably merged with the Mississaugas, sula south of the Indian River was controlled by the who had broken away from the Anishinaabeg and migrated Algonquian Nanticoke. -

Download Download

The Southern Algonquians and Their Neighbours DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba INTRODUCTION At least fifty named Indian groups are known to have lived in the area south of the Mason-Dixon line and north of the Creek and the other Muskogean tribes. The exact number and the specific names vary from one source to another, but all agree that there were many different tribes in Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas during the colonial period. Most also agree that these fifty or more tribes all spoke languages that can be assigned to just three language families: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan. In the case of a few favoured groups there is little room for debate. It is certain that the Powhatan spoke an Algonquian language, that the Tuscarora and Cherokee are Iroquoians, and that the Catawba speak a Siouan language. In other cases the linguistic material cannot be positively linked to one particular political group. There are several vocabularies of an Algonquian language that are labelled Nanticoke, but Ives Goddard (1978:73) has pointed out that Murray collected his "Nanticoke" vocabulary at the Choptank village on the Eastern Shore, and Heckeweld- er's vocabularies were collected from refugees living in Ontario. Should the language be called Nanticoke, Choptank, or something else? And if it is Nanticoke, did the Choptank speak the same language, a different dialect, a different Algonquian language, or some completely unrelated language? The basic problem, of course, is the lack of reliable linguistic data from most of this region. But there are additional complications. It is known that some Indians were bilingual or multilingual (cf. -

The Power of the Appalachian Trail: Reimagining the Nature

THE POWER OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL: REIMAGINING THE NATURE NARRATIVE THROUGH AUTOHISTORIA-TEORÍA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MULTICULTURAL WOMEN’S AND GENDER STUDIES COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY PAMELA WHITE WOLSEY, B.A., M.A. DENTON, TEXAS MAY 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Pamela White Wolsey DEDICATION For Earle ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Mom, Dad, Tina, Maxine, and Reba, your unconditional love and continued support does not go unnoticed, and I am so fortunate to have each of you in my life. To Medeski, Edie, and VL, as well as the rhodies, mountain chickens, and wood thrush, thank you for sharing your spirit and teaching me the joys of interspecies relationships. I cannot express enough gratitude to my committee and committee chair, AnaLouise Keating, for her guidance and inspiration. You made a profound impact on my personal and professional growth. My heartfelt appreciation is for my husband and hiking companion, Josh. Thank you for the tears, beers, and encouragement both on and off the trail. The AT and the dissertation were both incredible journeys, and I look forward to our next adventure together. iii ABSTRACT PAMELA WHITE WOLSEY THE POWER OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL: REIMAGINING THE NATURE NARRATIVE THROUGH AUTOHISTORIA-TEORÍA MAY 2020 This study situates the Appalachian Trail (AT) as a powerful place connecting multiple communities with varying identities, abilities, and personalities, a place where we can consider our radical interconnectedness in a way that moves beyond wilderness ideology and settler colonialism through the construction of an inclusive narrative about experiences in nature. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

Looking Forward by Looking Back

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY / WINTER 2021 LOOKING FORWARD BY LOOKING BACK CONTENTS / WINTER 2021 12 / ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Who we are, how we got here, and how we find the path forward 16 / NATIVE LANDS CONTENTS / WINTER 2021 Indigenous American lands along the A.T. 24 / THE A.T. AND RACE 06 / CONTRIBUTORS Reckoning with the past opens the door to an equitable future 08 / PRESIDENT’S LETTER 10 / LETTERS 26 / PREPARING FOR 52 / VOICES OF DEDICATION THE TRAIL 46 / TRAIL STORIES Unfiltered determination sets the tone for a beautiful adventure A close call with Mother Nature 30 / HEADING TOWARD 48 / INDIGENOUS TRUE NORTH The American chestnut tree Finding an authentic path to justice 54 / PARTING THOUGHT Home and the rhythm of nature 34 / WE WERE THERE, TOO Pioneering A.T. Women ON THE COVER Appalachian Trail near Mount Rogers, 38 / CHANGING OUTDOOR Virginia — which intersects with the Native American territory lands of the Moneton Nation. REPRESENTATION The A.T. runs through 22 Native Nations’ traditional & NARRATIVES territories and holds an abundant amount of Building a relationship with the outdoors Indigenous history. Photo by Jeffrey Stoner Above: Rocky Fork Creek along the A.T. corridor in 42 / TRAIL AS MUSE Lamar Alexander Rocky Fork State Park, Tennessee/ Appalachian Trail impressions North Carolina intersects with the Native American territory lands of the S’atsoyaha Nation. Photo by Jerry Greer THE MAGAZINE OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL CONSERVANCY / WINTER 2021 ATC EXECUTIVE LEADERSHIP MISSION Sandra Marra / President & CEO The Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to protect, manage, and Nicole Prorock / Chief Financial Officer advocate for the Appalachian Shalin Desai / Vice President of Advancement National Scenic Trail. -

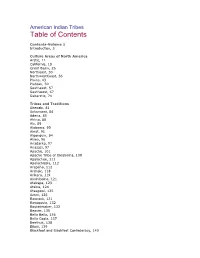

Table of Contents

American Indian Tribes Table of Contents Contents-Volume 1 Introduction, 3 Culture Areas of North America Arctic, 11 California, 19 Great Basin, 26 Northeast, 30 NorthwestCoast, 36 Plains, 43 Plateau, 50 Southeast, 57 Southwest, 67 Subarctic, 74 Tribes and Traditions Abenaki, 81 Achumawi, 84 Adena, 85 Ahtna, 88 Ais, 89 Alabama, 90 Aleut, 91 Algonquin, 94 Alsea, 96 Anadarko, 97 Anasazi, 97 Apache, 101 Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 108 Apalachee, 111 Apalachicola, 112 Arapaho, 112 Archaic, 118 Arikara, 119 Assiniboine, 121 Atakapa, 123 Atsina, 124 Atsugewi, 125 Aztec, 126 Bannock, 131 Bayogoula, 132 Basketmaker, 132 Beaver, 135 Bella Bella, 136 Bella Coola, 137 Beothuk, 138 Biloxi, 139 Blackfoot and Blackfeet Confederacy, 140 Caddo tribal group, 146 Cahuilla, 153 Calusa, 155 CapeFear, 156 Carib, 156 Carrier, 158 Catawba, 159 Cayuga, 160 Cayuse, 161 Chasta Costa, 163 Chehalis, 164 Chemakum, 165 Cheraw, 165 Cherokee, 166 Cheyenne, 175 Chiaha, 180 Chichimec, 181 Chickasaw, 182 Chilcotin, 185 Chinook, 186 Chipewyan, 187 Chitimacha, 188 Choctaw, 190 Chumash, 193 Clallam, 194 Clatskanie, 195 Clovis, 195 CoastYuki, 196 Cocopa, 197 Coeurd'Alene, 198 Columbia, 200 Colville, 201 Comanche, 201 Comox, 206 Coos, 206 Copalis, 208 Costanoan, 208 Coushatta, 209 Cowichan, 210 Cowlitz, 211 Cree, 212 Creek, 216 Crow, 222 Cupeño, 230 Desert culture, 230 Diegueño, 231 Dogrib, 233 Dorset, 234 Duwamish, 235 Erie, 236 Esselen, 236 Fernandeño, 238 Flathead, 239 Folsom, 242 Fox, 243 Fremont, 251 Gabrielino, 252 Gitksan, 253 Gosiute, 254 Guale, 255 Haisla, 256 Han, 256 -

Paleoindian Period Archaeology of Georgia

University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology Series Report No. 28 Georgia Archaeological Research Design Paper No.6 PALEOINDIAN PERIOD ARCHAEOLOGY OF GEORGIA By David G. Anderson National Park Service, Interagency Archaeological Services Division R. Jerald Ledbetter Southeastern Archeological Services and Lisa O'Steen Watkinsville October, 1990 I I I I i I, ...------------------------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES ..................................................................................................... .iii TABLES ....................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. v I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Organization of this Plan ........................................................... 1 Environmental Conditions During the PaleoIndian Period .................................... 3 Chronological Considerations ..................................................................... 6 II. PREVIOUS PALEOINDIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN GEORGIA. ......... 10 Introduction ........................................................................................ 10 Initial PaleoIndian Research in Georgia ........................................................ 10 The Early Flint Industry at Macon .......................................................... l0 Early Efforts With Private Collections -

Siouan Tribes of the Ohio Valley

Siouan Tribes of the Ohio Valley: “Where did all those Indians come from?” Robert L. Rankin Professor Emeritus of Linguistics The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66044 The fake General Custer quotation actually poses an interesting general question: How can we know the locations and movements of Native Peoples in pre- and proto-historic times? There are several kinds of evidence: 1. Evidence from the oral traditions of the people themselves. 2. Evidence from archaeology, relating primarily to material culture. 3. Evidence from molecular genetics. 4. Evidence from linguistics. The concept of FAMILY OF LANGUAGES • Two or more languages that evolved from a single language in the past. 1. Latin evolved into the modern Romance languages: French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian, etc. 2. Ancient Germanic (unwritten) evolved into modern English, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, etc. Illustration of a language family with words from Germanic • English: HOUND HOUSE FOOT GREEN TWO SNOW EAR • Dutch: hond huis voet groen twee sneeuw oor • German: Hund Haus Fuss Grün Zwei Schnee Ohr • Danish: hund hus fod grøn to sne øre • Swedish: hund hus fot grön tvo snö öra • Norweg.: hund hus fot grønn to snø øre • Gothic: hus snaiws auso • Here, the clear correspondences among these very basic concepts and accompanying grammar signal a single common origin for all of these different languages, namely the original language of the Germanic tribes. Similar data for the Siouan language family. • DOG or • HORSE HOUSE FOOT TWO THREE FOUR -

A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina 1882-1975

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1976 A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina 1882-1975 Jerry D. Lee Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Lee, Jerry D., "A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina 1882-1975" (1976). Theses and Dissertations. 4871. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 44 A STUDY OF THE theinfluenceINFLUENCE OF THE MORMON CHURCH ON THE CATAWBA INDIANS OF SOUTH CAROLINA 1882 1975 A thesis presented to the department of history brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jerryterry D lee december 1976 this thesis by terry D lee is accepted in its present form by the department of history of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of master of arts ted T wardwand comcitteemittee chairman r eugeeugenfeeugence E campbell ommiaeommiadcommitcommiliteeCommilC tciteelteee member 0 4 ralphvwitebcwiB smith committee member A 2.2 76 L dandag ted J weamerwegmerwagmer