The Monacan Indian Nation in the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

51St Annual Meeting March 25-29, 2021 Virtual Conference

51st Annual Meeting March 25-29, 2021 Virtual Conference 1 MAAC Officers and Executive Board PRESIDENT PRESIDENT-ELECT Bernard Means Lauren McMillan Virtual Curation Laboratory and University of Mary Washington School of World Studies Virginia Commonwealth University 1301 College Avenue 313 Shafer Street Fredericksburg, VA 22401 Richmond, VA 23284 [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Dr. Elizabeth Moore, RPA John Mullen State Archaeologist Virginia Department of Historic Resources Thunderbird Archeology, WSSI 2801 Kensington Avenue 5300 Wellington Branch Drive, Suite 100 Richmond, VA 23221 Gainesville, VA 20155 [email protected] [email protected] RECORDING SECRETARY BOARD MEMBER AT LARGE Brian Crane David Mudge Montgomery County Planning Department 8787 Georgia Ave 2021 Old York Road Silver Spring, MD 20910 Burlington, NJ 08016 [email protected] [email protected] BOARD MEMBER AT LARGE/ JOURNAL EDITOR STUDENT COMMITTEE CHAIR Katie Boyle Roger Moeller University of Maryland, College Park Archaeological Services 1554 Crest View Ave PO Box 386 Hagerstown, MD 21740 Bethlehem, CT 06751 [email protected] [email protected] 2 2020 MAAC Student Sponsors The Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference and its Executive Board express their deep appreciation to the following individuals and organizations that generously have supported the undergraduate and graduate students presenting papers at the conference, including those participating in the student paper competition. In -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Vol

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 96, NO. 4, PL. 1 tiutniiimniimwiuiiii Trade Beads Found at Leedstown, Natural Size SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 96. NUMBER 4 INDIAN SITES BELOW THE FALLS OF THE RAPPAHANNOCK, VIRGINIA (With 21 Plates) BY DAVID I. BUSHNELL, JR. (Publication 3441) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SEPTEMBER 15, 1937 ^t)t Boxb (jBaliimore (prttfe DAI.TIMORE. MD., C. S. A. CONTENTS Page Introduction I Discovery of the Rappahannock 2 Acts relating to the Indians passed by the General Assembly during the second half of the seventeenth century 4 Movement of tribes indicated by names on the Augustine Herrman map, 1673 10 Sites of ancient settlements 15 Pissaseck 16 Pottery 21 Soapstone 25 Cache of trade beads 27 Discovery of the beads 30 Kerahocak 35 Nandtanghtacund 36 Portobago Village, 1686 39 Material from site of Nandtanghtacund 42 Pottery 43 Soapstone 50 Above Port Tobago Bay 51 Left bank of the Rappahannock above Port Tobago Bay 52 At mouth of Millbank Creek 55 Checopissowa 56 Taliaferro Mount 57 " Doogs Indian " 58 Opposite the mouth of Hough Creek 60 Cuttatawomen 60 Sockbeck 62 Conclusions suggested by certain specimens 63 . ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES Page 1. Trade beads found at Leedstown (Frontispiece) 2. North over the Rappahannock showing Leedstown and the site of Pissaseck 18 3. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 18 4. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 18 5. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 18 6. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 26 7. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 26 8. Specimens from site of Pissaseck 26 9. I. Specimens from site of Pissaseck. -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

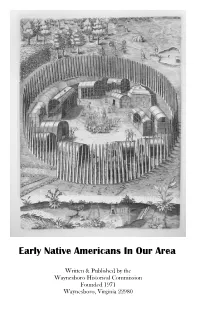

Native Americans in Our Area

Early Native Americans In Our Area Written & Published by the Waynesboro Historical Commission Founded 1971 Waynesboro, Virginia 22980 Dedication The Historic Commission of Waynesboro dedicates this publication to the earliest settlers of the North American Continent and in particular Virginia and our immediate region. Their relentless push through an unmarked environment exemplifies the quest of the human spirit to reach the horizon and make it its own. Until relatively recently, a history of America would devote a slight section to the Indian tribes discovered by the colonists who landed on the North American continent. The subsequent text would detail the claiming of the land, the creation of towns and villages, and the conquering of the forces that would halt the relentless move to the West. That view of history has been challenged by the work of archeologists who have used the advances in science and the skills of excavation to reveal a past that had been forgotten or deliberatively ignored. This publication seeks to present a concise chronicle of the prehistory of our country and our region with attention to one of the forgotten and marginalized civilizations, the Monacans who existed and prospered in Central Virginia and the areas immediate to Waynesboro. Migration to North America Well before the Romans, the Greeks, or the Egyptians created the culture we call Western Civilization, an ethnic group known as the “First People” began its colonization of the North American continent. There are a number of theories of how the original settlers came to the continent. Some thought they were the “Lost Tribes” of the Old Testament. -

Southern Indian Studies

Southern Indian Studies Volume 40 1991 Southern Indian Studies Published by The North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. 109 East Jones Street Raleigh, NC 27601-2807 Mark A. Mathis, Editor Officers of the Archaeological Society of North Carolina President: J. Kirby Ward, 101 Stourbridge Circle, Cary, NC 27511 Vice President: Richard Terrell, Rt. 5, Box 261, Trinity, NC 27370. Secretary: Vin Steponaitis, Research Laboratories of Anthropology, CB 3120, Alumni Building, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599. Treasurer: E. William Conen, 804 Kingswood Dr., Cary, NC 27513 Editor: Mark A. Mathis, Office of State Archaeology, 109 East Jones St., Raleigh, NC 27601-2807. At-Large Members: Stephen R. Claggett, Office of State Archaeology, 109 East Jones St., Raleigh, NC 27601-2807. R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., Research Laboratories of Anthropology, CB 3120, Alumni Building, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599. Robert Graham, 2140 Graham-Hopedale Rd., Burlington, NC 27215. Loretta Lautzenheiser, 310 Baker St., Tarboro, NC 27886. William D. Moxley, Jr., 2307 Hodges Rd., Kinston, NC 28501. Jack Sheridan, 15 Friar Tuck Lane, Sherwood Forest, Brevard, NC 28712. Information for Subscribers Southern Indian Studies is published once a year in October. Subscription is by membership in the North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. Annual dues are $10.00 for regular members, $25.00 for sustaining members, $5.00 for students, $15.00 for families, $150.00 for life members, $250.00 for corporate members, and $25.00 for institutional subscribers. Members also receive two issues of the North Carolina Archaeological Society Newsletter. Membership requests, dues, subscriptions, changes of address, and back issue orders should be directed to the Secretary. -

Ription E^ /£S -R ^ P2001.2/L-L#1875 James Surrett: "A Half Breed Cherokee Who Inhabits the Mountains of Bland County, Va

U. k'. Lh^oo^ Vhc^) s * ^ Cat! / Objectid / Objname Description E^ /£s -r ^ P2001.2/l-l#1875 James Surrett: "A half breed Cherokee who inhabits the mountains of Bland County, Va. Postcard -Photographs P2001.2/l-l#1876 M. M. Sutherland house Print, Photographic P2001.2/l-l#1876neg M. M. Sutherland house Negative, Film P2001.2/M#1877 Claude Swecker house, 4th St. and Withers Rd., WythevUle, Va. Print, Photographic P2001.2/l-l#1878 Claude Swecker house, 4th St. and Withers Rd., Wytheville, Va. Print, Photographic P2001.2/l-l#1879 Dr. James E. Tarter and family members standing beside carriage; copy of original owned by James E. Crockett. Print, Photographic r P2001.2/l-l#1879neg Dr. James E. Tarter and family members standing beside carriage; copy of original owned by James E. Crockett. Negative, Film P2001.2/l-l#1880 Dr. James E. Tarter and family members standing beside carriage; copy of original owned by James E. Crockett. Print, Photographic P2001.2/l-l#1881neg James E. Tarter Negative, Film P2001.2/I-1#1882 Dr. James E. Tarter house, 4th St., Wytheville, Va. Print, Photographic P2001.2/l-l#1883 Dr. James E. Tarter house, 4th St. and Washington St., Wytheville, Va. Print, Photographic Page 247 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description P2001.2/l-l#1884 Dr. James E. Tarter house, 4th St., and Washington St., Wytheville, Va. Print, Photographic P2001.2/l-l#1885neg Tarter house. Stony Fork; negative of original photograph in F. B. Kegley Photograph Collection #985 Negative, Film P2001.2/l-l#1886neg Tarter house. -

U Ni Ted States Departmen T of the Interior

Uni ted States Departmen t of the Interior BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS WASHINGTON, D.C. 20245 • IN REPLY REFER TO; MAR 281984. Tribal Government ;)ervices-F A MEMORANDUM To: A!:sistant Secretary - Indian Affairs From: DE!Puty Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs (Operations) Subject: Rc!cornmendation and Summary of Evidence for Proposed Finding Against FE!deral Acknowledgment of the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc. Pursuant to 25 CFR 83. Recom mendatiol We recommend thut the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc • (hereinafter "UGN") not be acknowledged as an Indian tribe entitled to a government to-government ]'elationship with the United States. We further recommend that a letter of the proposecl dc:!termination be forwarded to the ULN and other interested parties, • and that a notiC!e of the proposed finding that they do not exist as an Indian tribe be published in th4~ P,ederal Register. General Conclusions The ULN is a recently formed organization which did not exist prior to 1976. The organization WHS c!onceived, incorporated and promoted by one individual for personal interests and ,Ud not evolve from a tribal entity which existed on a substantially continuous bash from historical times until the present. The ULN has no relation to the Lumbees of the Robeson County area in North Carolina (hereinafter "Lumbees") historically soci.ally, genealogically, politically or organizationally. The use of the name "Lumbee" by Ule lILN appears to be an effort on the part of the founder, Malcolm L. Webber (aka Chief Thunderbird), to establish credibility in the minds of recruits and outside organiz Ilticlns. -

Clarify Occaneechi Band of Saponi Nation

HOUSE BILL 600: Clarify Occaneechi Band of Saponi Nation. 2021-2022 General Assembly Committee: House Rules, Calendar, and Operations of the Date: May 11, 2021 House Introduced by: Reps. Graham, Riddell, Hurtado Prepared by: Brad Krehely Analysis of: First Edition Staff Attorney OVERVIEW: House Bill 600 would amend the State recognition of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation of North Carolina. CURRENT LAW: Chapter 71A of the General Statutes provides for the recognition of Indian Tribes by the State of North Carolina. BILL ANALYSIS: House Bill 600 would amend the statutory State recognition of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation of North Carolina (G.S. 71A-7.2) to provide that the Tribe shall continue to enjoy all their rights, privileges, and immunities as an American Indian Tribe with a recognized tribal governing body carrying out and exercising substantial governmental duties and powers similar to the State, being recognized as eligible for the special programs and services provided by the United States to Indians because of their status as Indians. EFFECTIVE DATE: The act would be effective when the bill becomes law. BACKGROUND: The language in House Bill 600 is consistent with the language that was added to G.S. 71A-5 for the Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe of North Carolina in S.L. 2006-111 and in G.S. 71A-3 for the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina in S.L. 2019-162. *Billy R. Godwin, Staff Attorney for the Legislative Analysis Division, contributed substantially to the drafting of this summary. Legislative Analysis Jeffrey Hudson Division Director H600-SMRN-63(e1)-v-2 919-733-2578 This bill analysis was prepared by the nonpartisan legislative staff for the use of legislators in their deliberations and does not constitute an official statement of legislative intent. -

Alexander Brown and the Renaissance of Virginia History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1947 Alexander Brown and the Renaissance of Virginia History Marvin E. Harvey College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Harvey, Marvin E., "Alexander Brown and the Renaissance of Virginia History" (1947). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624471. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-hqgz-7d58 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' u s s m tm nmm M B m HMAISSMSE OF fIMllfXA HISTORY Marrlfi E* garygy &3tbaiite$ in partial ftalfil&mt •of the Baqttiremaats of The College _ of William end liary for the degree of Haotor of Aria *W Table of Contents Chapter 1. Prefatory* * *.., * * * * *,......... Chapter II. toeestry and Early I*if e... *.. Chapter III. The Middle Tears I* Basisess Mfe#.».«**«»«**• £* Mterary life............ Chapter IP. The Apex and the Decline.. T Akemxider Brown and the Bmi&immm a£ SirglMa History Chapter X Prefatory Sot until tfeo second half of Use nineteenth, century, said then primarily m a result of the Influence of the Civil War, m m there a place in the curriculum of toe nationto public schools -

Campus Environment Presidential Ad Hoc Committee Final Report November 6, 2019

Campus Environment Presidential Ad Hoc Committee Final Report November 6, 2019 Prepared for: Troy Paino President University of Mary Washington Prepared by: The Campus Environment Presidential Ad Hoc Committee Associate Professor Michael Spencer, Chair Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. 11 Campus History: ......................................................................................................................................... 16 Results and Analysis ................................................................................................................................... 27 Quantitative Assessment ....................................................................................................................... 27 Qualitative Assessment: ........................................................................................................................ 31 Emil Schnellock’s Murals: ..................................................................................................................