Proposed Finding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piedmont District Clubs by Counties

Piedmont District of Virginia Federation of Garden Clubs Below is a list of member Garden Clubs by county or city. Location is listed by mailing address of club president. This is not necessarily representative of all club members nor necessarily where the club holds its meeting. However, this is a good approximation. Check clubs listed in neighboring counties and cities as well. If you are interested in contacting a club please send us an email from the ‘Contact’ page and someone will be in contact with you. Thank you! Clubs by Counties Amelia -Clay Spring GC Middlesex -Amelia County GC -Hanover Herb Guild -John Mitchell GC Arlington -Hanover Towne GC -Rock Spring GC -Newfound River GC New Kent Brunswick -Old Ivy GC -Hanover Towne GC Caroline -Pamunkey River GC Charles City -West Hanover GC Northumberland -Chesapeake Bay GC Chesterfield Henrico -Kilmarnock -Bon Air GC -Crown Grant GC -Rappahannock GC -Chester GC -Ginter Park GC -Crestwood Farms GC -Green Acres GC Nottoway -Glebe Point GC -Highland Springs GC -Crewe -Greenfield GC -Hillard Park GC -Midlothian GC -Northam GC Powhatan -Oxford GC - Richmond Designers’ -Powhatan - Richmond Designers’ Guild* Guild* -River Road GC Prince William -Salisbury GC -Roslyn Hills GC -Manassas GC -Stonehenge GC -Sleepy Hollow GC -Woodland Pond GC -Thomas Jefferson GC Prince George -Windsordale GC Richmond County Cumberland -Wyndham GC Southampton -Cartersville GC Spotsylvania Dinwiddie James City -Chancellor GC Essex King and Queen -Sunlight GC Fairfax King George Fluvanna King William Stafford -Fluvanna GC Lancaster Surry Goochland Louisa -Surry GC Greensville -Lake Anna GC Sussex -Sunlight GC Westmoreland Hanover Lunenburg -Westmoreland GC -Canterbury GC Page 1 of 2 *Members of Richmond Designers’ Guild are members of other garden clubs and are from all areas. -

Westmoreland Davis Memorabilia SC 0036

Collection SC 0036 Westmoreland Davis Memorabilia 1917 Table of Contents User Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Container List Stephanie Adams Hunter 22 May 2008 Thomas Balch Library 208 W. Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 USER INFORMATION VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 6 items COLLECTION DATES: 1917 PROVENANCE: Franklin T. Payne, Middleburg, VA. ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: Collection open for research. USE RESTRICTIONS: No physical characteristics affect use of this material. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from Thomas Balch Library. CITE AS: Westmoreland Davis Memorabilia (SC 0036), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None. OTHER FINDING AIDS: None TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: Westmoreland Davis Political Collection (SC 0020), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. ACCESSION NUMBERS: 2008.0070 NOTES: None 2 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Westmoreland Davis was born at sea, 21 August 1859, to Annie Morriss (ca. 1835-25 Jan 1921) and Thomas Gordon Davis (1828-1860). Thomas Davis managed five plantations in Mississippi, including two inherited by his wife, and spent much of his time traveling. Annie Davis spent most of her time at his family home in Stateburg, SC. Shortly after Westmoreland Davis’ birth, his father, brother and sister died in quick succession. He and his mother moved to Richmond, VA to live with her uncle Richard Morriss (ca. 1822-1867). After the end of the Civil War the Davis’s were reduced to penury by the mismanagement of their plantations and legal obstacles to monies from bonds purchased by her father, Christopher Staats Morriss (1797-1850). Davis entered Virginia Military Institute as a scholarship student in 1873 at the age of 14. -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

M N Gazette of the College of William & Mary in Virginia Volume V

M N GAZETTE OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM & MARY IN VIRGINIA VOLUME V. WILLIAMSBURG, VA., TUESDAY, AUGUST 31, 1937 NO. 1 CHARLES P. McCURDY SELECTED FOR d Attend ]) COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES BRING ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE SECRETARY | Homecoming I MANY TO WILLIAMSBURG IN JUNE Was Prominent in the Affairs of Da Washington, D. C. W.&M. OLDEST LIVING ALUMNUS I y \ WHITTINGTON APPOINTED Said to Be One of Largest Alumni Club. Groups to Return to William OBSERVES 83RD BITHDAY d SATURDAY, 5 and Mary Campus. Announcement of the appointment § NOVEMBER 13 ? NYA HOMEMAKING HEAD of Charles Post McCurdy, Jr., to the John Peyton Little, oldest living al- The four days of commencement ac- tivities and festivities, June 4-7, were post of Executive Secretary of the Al- umnus of the College was 83 on Aug- Announcement has been made by umni Association, has been made by ust 11th and celebrated his birthday Football participated in and greatly enjoyed by Dr. Walter S. Newman, State NYA one of the largest, if not the largest, President Sidney B. Hall. McCurdy, by a trip through part of a twenty-five William and Mary director, of the appointment of Ruby thousand acre tract of timber land. alumni groups that has ever returned prominent in the affairs of the Wash- VS. Whittington, B. S. '34, of Woodlawn, ington Alumni Club, -was a member of Still very active in the lumber busi- to this ancient and honorable campus. Va. to the position of supervisor of The program opened on Friday the Board of Managers of the Asso- ness, Mr. -

Transportation Where Are We Headed?

The magazine of the VOL. 49 NO. 9 NOV. 2014 Virginia Municipal League Transportation Where are we headed? Inside: VML Annual Conference photo highlights The magazine of the Virginia Municipal League VOL. 49 NO. 9 NOVEMBER 2014 About the cover Virginia’s future economic success will be tied inextricably to its ability to build a modern transportation network capable of moving more people and more goods efficiently. In this issue, Virginia Town & City takes a look at three evolving aspects of transportation in the state. Departments Discovering Virginia ............... 2 People ......................................... 3 News & Notes ........................... 5 Professional Directory ......... 28 Features Transportation funding: Former governor urges renewed Two steps forward, one step back, investment in aviation but now what? A former Virginia governor responsible for an unprecedented Less than two years ago following a decade of bickering, the state investment in transportation nearly 30 years ago warns General Assembly passed legislation designed to adequately that without a renewed commitment to aviation, Virginia and fund transportation in Virginia for the foreseeable future. the nation will cede a crucial economic advantage to other That bipartisan solution, however, already is showing signs parts of the world. By Gerald L. Baliles of stress. By Neal Menkes Page 15 Page 9 Thank-you Roanoke: Transit: The future may be VML Annual Conference riding on it The 2014 Virginia Municipal League Fifty years after passage of the landmark Annual Conference in Roanoke was a Urban Mass Transit Act of 1964, transit success thanks to the efforts of the host is playing a crucial role in building not city and an abundance of informative only vibrant 21st century communities, speakers, sponsors and exhibitors. -

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts: Its Founding, 1930-1936

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts: its Founding, 1930-1936 Elizabeth Geesey Holmes College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Holmes, Elizabeth Geesey, "The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts: its Founding, 1930-1936" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625838. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-xr1t-4536 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS ITS FOUNDING, 1930-1936 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Elizabeth Geesey Holmes 1993 Copyright © 1993 by Elizabeth Geesey Holmes APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Approved, August 1993 Richard B . Sherman Philip j /j) FunigielJ^o• ^ Douglas Smith Colonial WilvLiamsburg Foundation DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband, Jim, my sister, Kate, and my parents, Ron and Jean Geesey. Without their love, support and encouragement I could not have completed this project and degree. -

Ss.Ff=?H= Lils Virginia Provision of the Act Is of with the Editor and First Y.-Ar in for a Two Proofreader Which Lend It Some Will Say

call of patriotism, nor would there Ijo if other professional athletes adopted a similar SONGS AND jRirfimonilCim^-Pi^pntrl) course, as they usually do. Tall or short, SAWS the professional athlete is apt to set so high hmTwth' I NOW YOU GIT TO WORK! a MrthlSit'" a store on his well-devoloped body that lie Take Chincr. One of the Day's Beat Cartoons. Of course, ~ SK1 TUB TIMES, Founded 1S8S will uot endanger it out of the lino of busi- you cannot always make .E ¦""""" A THB DISPATCH, Founded 1S30 ness, and not one or ruore of play Just as you'd like to. infrequently For oft, when sliding safe to base, PW°alyi.Ma TSVMry his organs are so hypertrophied that he A cruel fate will spike you. would collapse in the early stages of a hard But yet a man that scoots for home, Pabltohrd etfrr ilty In the year by Thr Tlmrn- Whene'er luck Dtiyalrk Publishing Company, Inc. Address nit campaign. seems to beckon, roaiRtialralloni to Whether tall or men make the Although lie's tagged before he scores, War News Years TKK TIMES-DISPATCH, short better Is bettor off. 1 reckon. Fifty Ago Ilmea-Dlapatch Hulldlnc, 10 South Tenth Street. soldiers is, the authorities say. a purely Than (!. rom the Richmond Dec. Richmond* Vn. he who lingers on tho bng, Dispatch, 21, 18»}<4.) academic question. The nverage Scotch Afraid of risks or chances. Highlander is long in the limb, and is spokeu ! Such dubs as he will ne'er be wooed Tho rumor on the streets yesterday that tho TELEPHONE. -

Blue Catfish in Virginia Historical Perspective & Importance To

Blue Catfish in Virginia Historical Perspective & Importance to Recreational Fishing David K. Whitehurst [email protected] Blue Catfish Introductions to James River & Rappahannock River 1973 - 1977 N James River Tidal James River Watershed Rappahannock River Tidal Rappahannock Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Blue Catfish Introduced to Mattaponi River in 1985 Blue CatfishFollowed ( Ictalurus by Colonization furcatus ) Introductions of the Pamunkey York River River System Mattaponi River 1985 Pamunkey River ???? N James River Tidal James River Watershed Rappahannock River Tidal Rappahannock Watershed York River Tidal York Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Blue Catfish Established in Potomac River – Date ? Blue Catfish ( Ictalurus furcatus ) Introductions EstablishedConfirmed in in Potomac Piankatank River (SinceRiver ????)– 2002 Recently Discovered in Piankatank River N Piankatank / Dragon Swamp Tidal Potomac - Virginia James River Tidal James River Watershed Rappahannock River Tidal Rappahannock Watershed York River Tidal York Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Blue Catfish Now Occur in all Major Virginia Blue Catfish ( Ictalurus furcatus ) Tributaries of Chesapeake Bay All of Virginia’s Major Tidal River Systems of Chesapeake Bay Drainage 2003 N Piankatank / Dragon Swamp Tidal Potomac - Virginia Tidal James River Watershed Tidal Rappahannock Watershed Tidal York Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Stocking in Virginia – Provide recreational and food value to anglers – Traditional Fisheries Management => Stocking – Other species introduced to Virginia tidal rivers: – Channel Catfish, – Largemouth Bass, – Smallmouth Bass, – Common carp, …. Blue catfish aside, as of mid-1990’s freshwater fish community in Virginia tidal waters dominated by introduced species. Blue Catfish Introductions Widespread Important Recreational Fisheries • Key factors determining this “success” – Strong recruitment and good survival leading to very high abundance – Trophy fishery dependant on rapid growth and good survival > 90 lb. -

2016-2017 Course Catalog

2016-2017 Course Catalog 2016-2017 MERCYHURST NORTH EAST ACADEMIC COURSE CATALOG Office of Admissions 16 West Division Street• North East, PA 16428 (814)725-6100 • (814)725-6144 [email protected] This catalog represents the most accurate information on Mercyhurst North East available at the time of printing. The University reserves the right to make alterations in its programs, regulations, fees, and other policies as warranted. Mercyhurst University Vision Statement Mercyhurst University seeks to be a leading higher education intuition that integrates excellence in the liberal arts, professional and career-path programs, and service to regional and world communities. Mission Statement Consistent with its Catholic identity and Mercy heritage, Mercyhurst University educates women and men in a culture where faith and reason flourish together, where beauty and power of the liberal arts combine with an appreciation for the dignity of work and a commitment to serving others. Confident in the strength of its student-faculty bonds, the university community is inspired by the image of students whose choices, in life and work, will enable them to realize the human and spiritual values embedded in everyday realities and to exercise leadership in service toward a just world. Core Values We are… Socially Merciful, Mercy restores human dignity, expands our social relations, and empowers us to reach out in compassion to others. Globally responsible, Globalization challenges us to learn how to steward the resources of the Earth wisely and to act in solidarity with its diverse peoples. Compassionately hospitable, Mercy hospitality begins with self-acceptance, welcomes peoples of different faith, ethnic, and cultural traditions, and thus builds communities that transcend mere tolerance. -

York River Water Budget

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1-29-2009 York River Water Budget Carl Hershner Virginia Institute of Marine Science Molly Mitchell Virginia Institute of Marine Science Donna Marie Bilkovic Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie D. Herman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Hershner, C., Mitchell, M., Bilkovic, D. M., Herman, J. D., & Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. (2009) York River Water Budget. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V56S39 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YORK RIVER WATER BUDGET REPORT By the Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science January 29, 2009 Authors: Carl Hershner Molly Roggero Donna Bilkovic Julie Herman Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 3 Methods of determining instream flow requirement ....................................................................... 4 Hydrological methods..................................................................................................................... -

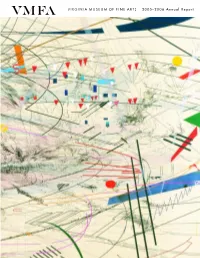

VMFA Annual Report 2005-2006

2005–2006 Annual Report Mission Statement Table of Contents VMFA is a state-supported, Officers and Directors . 2 Forewords . 4 privately endowed Acquisition Highlights educational institution Julie Mehretu . 8 Uma-Mahesvara. 10 created for the benefit Gustave Moreau. 12 of the citizens of the Victor Horta . 14 William Wetmore Story . 16 Commonwealth of Gifts and Purchases . 18 Virginia. Its purpose is Exhibitions . 22 to collect, preserve, The Permanent Collection. 24 The Public-Private Partnership. 32 exhibit, and interpret art, Educational Programs and Community Outreach. 36 to encourage the study Attendance: At the Museum and Around the State . 44 of the arts, and thus to Behind the Scenes at VMFA. 45 The Campaign for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts . 48 enrich the lives of all. Honor Roll of Contributors. 60 Volunteer and Support Groups . 72 Advisory Groups . 72 Financial Statements. 73 Staff . 74 Credits . 76 Cover: Stadia III (detail), 2004, by Julie Mehretu (American, born Ethopia Publication of this report, which covers the fiscal year July 1, 2005, to June 30, 1970), ink and acrylic on canvas, 107 inches high by 140 inches wide (Museum 2006, was funded by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Foundation. Purchase, The National Endowment for the Arts Fund for American Art, and Web site: www.vmfa.museum partial gift of Jeanne Greenberg Rohalyn, 2006.1; see Acquisition Highlights). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia 23221-2466 USA Right: Buffalo Mask, African (Mama Culture, Nigeria), 19th–20th century, © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Foundation. All rights reserved. wood and pigment, 171/4 inches high by 137/8 inches wide by 14 3/4 inches Printed in the United States of America. -

Academic Course Catalog 2017-2018

2017-2018 Course Catalog ACADEMIC COURSE CATALOG 2017-2018 16 West Division Street• North East, PA 16428 (814)725-6100 northeast.mercyhurst.edu This catalog represents the most accurate information on Mercyhurst North East available at the time of printing. The university reserves the right to make alterations in its programs, regulations, fees, and other policies as warranted. Mercyhurst University Vision Statement Mercyhurst University seeks to be a leading higher education intuition that integrates excellence in the liberal arts, professional and career-path programs, and service to regional and world communities. Mission Statement Consistent with its Catholic identity and Mercy heritage, Mercyhurst University educates women and men in a culture where faith and reason flourish together, where beauty and power of the liberal arts combine with an appreciation for the dignity of work and a commitment to serving others. Confident in the strength of its student-faculty bonds, the university community is inspired by the image of students whose choices, in life and work, will enable them to realize the human and spiritual values embedded in everyday realities and to exercise leadership in service toward a just world. Core Values We are… Socially Merciful, Mercy restores human dignity, expands our social relations, and empowers us to reach out in compassion to others. Globally responsible, Globalization challenges us to learn how to steward the resources of the Earth wisely and to act in solidarity with its diverse peoples. Compassionately hospitable, Mercy hospitality begins with self-acceptance, welcomes peoples of different faith, ethnic, and cultural traditions, and thus builds communities that transcend mere tolerance.