Census of in Di A, 190 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

David Scott in North-East India 1802-1831

'Its interesting situation between Hindoostan and China, two names with which the civilized world has been long familiar, whilst itself remains nearly unknown, is a striking fact and leaves nothing to be wished, but the means and opportunity for exploring it.' Surveyor-General Blacker to Lord Amherst about Assam, 22 April, 1824. DAVID SCOTT IN NORTH-EAST INDIA 1802-1831 A STUDY IN BRITISH PATERNALISM br NIRODE K. BAROOAH MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL, NEW DELHI TO THE MEMORY OF DR. LALIT KUMAR BAROOAH PREFACE IN THE long roll of the East India Company's Bengal civil servants, placed in the North-East Frontier region. the name of David Scott stands out, undoubtably,. - as one of the most fasci- nating. He served the Company in the various capacities on the northern and eastern frontiers of the Bengal Presidency from 1804 to 1831. First coming into prominrnce by his handling of relations with Bhutan, Sikkim, and Tibet during the Nepal war of 1814, Scott was successively concerned with the Garo hills, the Khasi and Jaintia hills and the Brahma- putra valley (along with its eastern frontier) as gent to the Governor-General on the North-East Frontier of Bengal and as Commissioner of Assam. His career in India, where he also died in harness in 1831, at the early age of forty-five, is the subject of this study. The dominant feature in his ideas of administration was Paternalism and hence the sub-title-the justification of which is fully given in the first chapter of the book (along with the importance and need of such a study). -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

1Edieval Assam

.-.':'-, CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION : Historical Background of ~1edieval Assam. (1) Political Conditions of Assam in the fir~t half of the thirt- eenth Century : During the early part of the thirteenth Century Kamrup was a big and flourishing kingdom'w.ith Kamrupnagar in the· North Guwahat.i as the Capital. 1 This kingdom fell due to repeated f'.1uslim invasions and Consequent! y forces of political destabili t.y set in. In the first decade of the thirteenth century Munammedan 2 intrusions began. 11 The expedition of --1205-06 A.D. under Muhammad Bin-Bukhtiyar proved a disastrous failure. Kamrtipa rose to the occasion and dealt a heavy blow to the I"'!Uslim expeditionary force. In 1227 A.D. Ghiyasuddin Iwaz entered the Brahmaputra valley to meet with similar reverse and had to hurry back to Gaur. Nasiruddin is said to have over-thrown the I<~rupa King, placed a successor to the throne on promise of an annual tribute. and retired from Kamrupa". 3 During the middle of the thirteenth century the prosperous Kamrup kingdom broke up into Kamata Kingdom, Kachari 1. (a) Choudhury,P.C.,The History of Civilisation of the people of-Assam to the twelfth Cen tury A.D.,Third Ed.,Guwahati,1987,ppe244-45. (b) Barua, K. L. ,·Early History of :Kama r;upa, Second Ed.,Guwahati, 1966, p.127 2. Ibid. p. 135. 3. l3asu, U.K.,Assam in the l\hom J:... ge, Calcutta, 1 1970, p.12. ··,· ·..... ·. '.' ' ,- l '' '.· 2 Kingdom., Ahom Kingdom., J:ayantiya kingdom and the chutiya kingdom. TheAhom, Kachari and Jayantiya kingdoms continued to exist till ' ' the British annexation: but the kingdoms of Kamata and Chutiya came to decay by- the turn of the sixteenth century~ · . -

Socio-Political Development of Surma Barak Valley from 5 to 13 Century

Pratidhwani the Echo A Peer-Reviewed International Journal of Humanities & Social Science ISSN: 2278-5264 (Online) 2321-9319 (Print) Impact Factor: 6.28 (Index Copernicus International) Volume-VIII, Issue-I, July 2019, Page No. 207-214 P ublished by Dept. of Bengali, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India Website: http://www.thecho.in Socio-Political Development of Surma Barak Valley from 5th to 13th Century A.D. Mehbubur Rahman Choudhury Ph.D Research Scholar, University of Science & Technology, Meghalaya Dr. Sahab Uddin Ahmed Associate Professor, History, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam Abstract The Barak Valley of Assam consists of three districts, viz. Cachar, Hailakandi and Karimganj situated between Longitude 92.15” and 93.15” East and Latitude 24.8” and 25.8” North and covering an area of 6,941.2 square Kilometres, this Indian portion of the valley is bounded on the north by the North Cachar Hills District of Assam and the Jaintia Hills District of Meghalaya, on the east by Manipur, on the south by Mizoram and on the west by Tripura and the Sylhet District of Bangladesh. These three districts in Assam, however, together form the Indian part of a Valley, the larger portion of which is now in Bangladesh. The valley was transferred to Assam from Bengal in 1874 and the Bangladesh part was separated by the partition of India in 1947. The social and polity formation processes in the Barak Surma Valley in the Pre-Colonial period were influenced by these geo-graphical, historical and sociological factors. On the one hand, it was an outlying area of the Bengal plains and on the other hand, it was flanked by the hill tribal regions. -

Assessment of Water Quality of Lungding Stream Through Biomonitoring

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2017): 7.296 Assessment of Water Quality of Lungding Stream through Biomonitoring Nilu Paul1, A. K. Tamuli2, R. Teron3, J. Arjun4 1Department of Zoology, Lumding College, Lumding, Assam, India 2Department of Life Science and Bioinformatics, Assam University Diphu Campus, Diphu, Assam, India 3Department of Life Science and Bioinformatics, Assam University Diphu Campus, Diphu, Assam, India 4Department of Zoology, Lumding College, Lumding, Assam, India Abstract: Stream ecosystem biomonitoring has been widely used to assess the status of water. It provides information on the health of an ecosystem based on which organisms live in a waterbody. The benthic community is dependent on its surrounding and therefore, it serves as an indicator that reflects the overall condition of the ecosystem. Among the commonly used biomoniting approaches, biotic indices and multimetric approaches are most frequently used to evaluate the environment health of streams and rivers. The macro invertebrate fauna and physico-chemical parameters of Lungding stream of Dima Hasao district were studied seasonally from March 2017 to February 2018. A total of 13 species of benthic invertebrate fauna belonging to three phyla (Annelida, Arthropoda and Mollusca), five classes (Hirudinea, Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Crustacea, Insecta) and thirteen families (Hirudinidae, Physidae, Anomidae, Gammaridae,Panaediae, Baetidae Aeshnidae, Belostometidae, Hydrophilidae, Chaoboridae, Chironomidae) were found in the Lungding stream during the study. Gastropoda was predominant (23.71 %) followed by Crustacea, Bivalvia and Hirudinidae with percentage composition of 19%, 16.59% and 11.42% respectively. Among Insects, Dipteran midges (Chaoboridae) with 8.84% were the dominant group. -

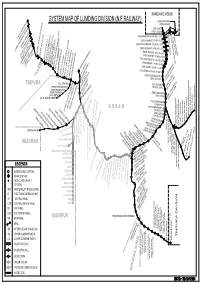

System Map of Lumding Division (N.F.Railway) (Apu) Anipur (Rtbr) Ratabari Mp/I(R) B Class (Pkgm) Phakhoagram (Bzgt) Bazarghat (Pasg) Panisagar

RANGIYA DIVISION SYSTEM MAP OF LUMDING DIVISION (N.F.RAILWAY) (CGS) CHANGSARI CSP/II(R) B CLASS (AZR) AZARA CSP/II(R) B CLASS (KYQ) KAMAKHYA JN. RRI/II(R) B CLASS CL OF SARAIGHAT(AGT) BR. AGTHORI (AGTL) AGARTALA (PNO) PANDU EI/II(R) B CLASS CP/II(R) B CLASS (GHY) GUWAHATI EP/I(R) B CLASS (NGC) NEW GUWAHATI CP/II(R) SPL CLASS (JRNA) JIRANIA CP/II(R) B CLASS (NMY) NOONMATI CP/II(R) SPL CLASS (JGNR) JOGENDRA NAGAR (NNGE) NARANGI CP/II(R) B CLASS (JWNR) JAWAHAR NAGAR (TLMR) TELIAMURA (SKAP) S.K.PARA (PHI) PANIKHAITI CP/II(R) B CLASS CP/II(R) B CLASS (NLKT) NALKATA (TKC) THAKURKUCHI (KUGT) KUMARGHAT CP/II(R) B CLASS CP/II(R) (PEC)B CLASS PENCHARTHAL MP/I(R) B CLASS (MGKM) MUNGIAKAMI (PASG) PANISAGAR (PNB) PANBARI MP/I(R) B CLASS CP/II(R) B CLASS CP/II(R)(ABSA) B CLASS AMBASSA CP/II(R) B CLASS MANU (DMR) DHARMANAGAR (DGU) DIGARU CP/II(R) B CLASS (NPU) NADIAPUR (MSSN) MAISHASHAN (TTLA) TETELIA (CBZ) CHURAIBARI CSP/II(R) B CLASS (TBX) TILBHUM (KKGT) KALKALIGHAT CP/II(R) B CLASS (CHBN) CHANDKHIRA BAGAN (LGI) LANGAI (KKET) KAMRUPKHETRI (PTKD) PATHARKANDI (BRHU) BARAHU (KNBR) KANAIBAZAR(BRGM) BARAIGRAM CSP/II(R) B CLASS (KXJ) KARIMGANJ CSP/II(R) B CLASS TRIPURA UQ/I B CLASS (ELL) ERALIGUL (JID) JAGIROAD (PKGM) PHAKHOAGRAM (CGX) CHARGOLA CSP/II(R) B CLASS (AJRE) AUJURI (BZGT) BAZARGHAT CSP/II(R) B CLASS (RTBR) RATABARI (BXG) BHANGA (SNBR) SONUABARI UQ/I B CLASS (APU) ANIPUR CP/II(R) B CLASS (DLCR) DULLABCHERRA (DML) DHARAMTUL (RPB) RUPASIBARI CSP/II(R) B CLASS (TGE) THEKERAGURI CSP/II(R) B CLASS (SQF) SUKRITIPUR A S S A M (CPK) CHAPARMUKH JN. -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

The Insecure World of the Nation

The Insecure World of the Nation Ranabir Samaddar In The Marginal Nation, which dealt with transborder migration from Bangladesh to West Bengal, two moods, two mentalities, and two worlds were in description – that of cartographic anxiety and an ironic unconcern. In that description of marginality, where nations, borders, boundaries, communities, and the political societies were enmeshed in making a nonnationalised world, and the citizenmigrant (two animals yet at the same time one) formed the political subject of this universe of transcendence, interconnections and linkages were the priority theme. Clearly, though conflict was an underlying strain throughout the book, the emphasis was on the human condition of the subject the migrant’s capacity to transgress the various boundaries set in place by nationformation in South Asia. Therefore, responding to the debate on the numbers of illegal migrants I termed it as a “numbers game”. My argument was that in this world of edges, the problem was not what was truth (about nationality, identity, and numbers), but truth (of nationality, identity, and numbers) itself was the problem.1 Yet, this was an excessively humanised description, that today on hindsight after the passing of some years since its publication, seems to have downplayed the overwhelming factor of conflict and wars that take place because “communities must be defended” – one can say the “permanent condition” in which communities find themselves. On this rereading of the problematic the questions, which crop up are: -

In the Central Administrative Tribunal Kolkata Bench

1 •! I 1 J- : a/ % IN THE CENTRAL ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL KOLKATA BENCH* KOLKATA O.A. No.350/ / 72-^ of2019 HA'/Vo* 35'o/ 10 2,1/ 2-0 l*i 1. Jhama Das, wife of Umesh Chandra Das, aged about 46 years, by occupation Housewife. UlHa oa 2. Pinky Das, daughter of Umesh Chandra Das, aged about 25 years, by occupation Unemployed. Both residing at Kamarthuba, P.O. & P.S. Habra, District North 24- Parganas, Pin-743263. ... APPLICANTS VERSUS 1. Union of India through the General Manager, N.F. Railway, Maligaon, Shuttle Road, East Maligaon, Guwahati, Pin-781010. 2. Principal Chief Personnel Officer, N.F. Railway, Maligaon, Shuttle Road, East Maligaon, Guwahati, Pin- 781010. 3. Chief Vigilance Officer, N.F. Railway, Maligaon, Shuttle Road, East Maligaon, Guwahati, Pin- 781010. 4. Divisional Railway Manager, Lumding Division, North Frontier Railway, Lumding, Assam-782447. 5. Senior Divisional Personnel Officer, Lumding Division, North Frontier Railway, Lumding, Assam- 782447. 6. Sri Umesh Chandra Das, son of Late Rajani Kanta Das, working as !■ ESM-2, under Senior Section ' \\ Engineer, N.F. Railway, Guwahati- 781001, residing at Railway Quarter No.DS/14E, Kalibari Colony, P.O. Panbazar, P.S. Latasil Guwahati, Assam, Pin-781001 and permanently residing at Hengrabari, Lichu Bagan, Dispur, Kamrup, Assam-781006. 7. Smt. Ratna Barman, residing at Railway Quarter No.DS/14E, Kalibari Colony, P.O. Panbazar, P.S. Latasil Guwahati, Assam, Pin- 781001. o4.' ~ f LlduJk. *Dt4fttA-v VC***—- 7-$\eo6 ... RESPONDENTS •/ : ' / 1 f 1 x *• <3 CENTRAL ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL KOLKATA BENCH KOLKATA No.O A.350/1724/2019 M.A.350/1021/2019 Date of order: 14.01.2020 Coram : Hon'ble Mrs. -

Twenty Fifth Annual Report Annual Report 2017-18

TWENTY FFIFTHIFTH ANNUAL REPORT 20172017----18181818 ASSAM UNIVERSITY Silchar Accredited by NAAC with B grade with a CGPS OF 2.92 TWENTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 REPORT 2017-18 ANNUAL TWENTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 PUBLISHED BY INTERNAL QUALITY ASSURANCE CELL, ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR Annual Report 2017-18 ASSAM UNIVERSITY th 25 ANNUAL REPORT (2017-18) Report on the working of the University st st (1 April, 2017 to 31 March, 2018) Assam University Silchar – 788011 www.aus.ac.in Compiled and Edited by: Internal Quality Assurance Cell Assam University, Silchar | i Annual Report 2017-18 STATUTORY POSITIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY (As on 31.3.2018) Visitor : Shri Pranab Mukherjee His Excellency President of India Chief Rector : Shri Jagdish Mukhi His Excellency Governor of Assam Chancellor : Shri Gulzar Eminent Lyricist and Poet Vice-Chancellor : Prof Dilip Chandra Nath Deans of Schools: (As on 31.3.2018) Prof. G.P. Pandey : Abanindranath Tagore School of Creative Arts & Communication Studies Prof. Asoke Kr. Sen : Albert Einstein School of Physical Sciences Prof. Nangendra Pandey : Aryabhatta School of Earth Sciences Prof. Geetika Bagchi : Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay School of Education Prof. Sumanush Dutta : Deshabandhu Chittaranjan School of Legal Studies Prof. Dulal Chandra Roy : E. P Odum School of Environmental Sciences Prof. Supriyo Chakraborty : Hargobind Khurana School of Life Sciences Prof. Debasish Bhattacharjee : Jadunath Sarkar School of Social Sciences Prof. Apurbananda Mazumdar : Jawarharlal Nehru School of Management Prof. Niranjan Roy : Mahatma Gandhi School of Economics and Commerce Prof. W. Raghumani Singh : Rabindranath Tagore School of Indian Languages and Cultural Studies Prof. Subhra Nag : Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan School of Philosophical Studies Prof.