Polities and Ethnicities in North-East India Philippe Ramirez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lz-^ P-,^-=O.,U-- 15 15 No

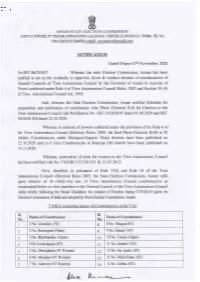

ASSAM STATE ELECTION COMMISSION ADITYA TOWER, 2}TD FI.,OO& DO\AAITO\^AI, G.S. ROAD DISPUR, GUWAHATI -781W. PTT. NO. M1263210/ 2264920 email - [email protected] NOTIFICATION Dated Dispur 17m November,2020 No.SEC.86l2020l7 : Whereas, the state Election Commission, Assam has been notified to act as the Authority to supervise, direct & conduct election of constituencies of General Councils of Tiwa Autonomous Council by the Governor of Assam in exercise of Power conferred under Rule 4 of Tiwa Autonomous Council Rules, 2005 and Section 50 (4) of Tiwa Autonomous Council Act, 1995; And, whereas, the State Election Commission, Assam notified Schedule for preparation and publication of constituency wise Photo Electoral Roll for Election to the Tiwa Autonomous Council vide Notification No. 5EC.5412020147 dated 01 .09.2020 and SEC 5 4 I 2020 I | 0 4 dated 22.1 0 .2020 ; Whereas, in exercise of powers conferred under the provision of the Rule 4 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council (Election) Rules, 2005, the final Photo Electoral Rolls in 30 (thirty) Constituencies under MorigaonA.lagaonl Hojai districts have been published on 22.10.2020 and in 6 (six) Constituencies in Kamrup (M) district have been published on t5.rr.2020; Whereas, reservation of seats for women in the Tiwa Autonomous Council has been notified vide No. TAD/BC/I5712015151 dt.21.07.2015; Now, therefore, in pursuance of Rule 17(I) and Rule 18 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council (Election) Rules 2005, the State Election Commission, Assam calls upon electors of 36 (thirfy-six) nos. of Tiwa Autonomous Council constituencies as enumerated below to elect members to the General Council of the Tiwa Autonomous Council while sfictly following the Broad Guidelines for conduct of Election dwing COVID-l9 given by Election Commission of India and adopted by State Election Commissioq Assam TABLE consistins names of Constituencies of the TAC sl. -

David Scott in North-East India 1802-1831

'Its interesting situation between Hindoostan and China, two names with which the civilized world has been long familiar, whilst itself remains nearly unknown, is a striking fact and leaves nothing to be wished, but the means and opportunity for exploring it.' Surveyor-General Blacker to Lord Amherst about Assam, 22 April, 1824. DAVID SCOTT IN NORTH-EAST INDIA 1802-1831 A STUDY IN BRITISH PATERNALISM br NIRODE K. BAROOAH MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL, NEW DELHI TO THE MEMORY OF DR. LALIT KUMAR BAROOAH PREFACE IN THE long roll of the East India Company's Bengal civil servants, placed in the North-East Frontier region. the name of David Scott stands out, undoubtably,. - as one of the most fasci- nating. He served the Company in the various capacities on the northern and eastern frontiers of the Bengal Presidency from 1804 to 1831. First coming into prominrnce by his handling of relations with Bhutan, Sikkim, and Tibet during the Nepal war of 1814, Scott was successively concerned with the Garo hills, the Khasi and Jaintia hills and the Brahma- putra valley (along with its eastern frontier) as gent to the Governor-General on the North-East Frontier of Bengal and as Commissioner of Assam. His career in India, where he also died in harness in 1831, at the early age of forty-five, is the subject of this study. The dominant feature in his ideas of administration was Paternalism and hence the sub-title-the justification of which is fully given in the first chapter of the book (along with the importance and need of such a study). -

Socio-Economic Significances of the Festivals of the Tiwas and the the Assamese Hindus of Middle Assam

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 5 May 2020 | ISSN: 2320-28820 SOCIO-ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCES OF THE FESTIVALS OF THE TIWAS AND THE THE ASSAMESE HINDUS OF MIDDLE ASSAM Abstract:- The Tiwas of Mongoloid group migrated to Assam and scattered into different parts of Nagaon, Morigaon and Karbi Anglong districts and settled with the Assamese Hindus as an inseparable part of their society. The Festivals observed by the Tiwas and the Assamese caste Hindus have their distinct identity and tradition. The festivals celebrated by these communities are both of seasonal and calenderic and some festivals celebrated time to time. Bihu is the greatest festival of the region and the Tiwas celebrate it with a slight variation. The Gosain Uliuwa Mela, Jonbeel Mela and the Barat festival are some specific festivals. Influence of Neo-Vaisnative culture is diffusively and widely seen in the festivals of the plain Tiwas and the other Assamese caste Hindus. The Committee Bhaona festival of Ankiya drama performance celebrated in Charaibahi area is a unique one. This paper is an attempt to look into the socio-economic significances of the festivals of the Tiwas and Assamese Hindus of Middle Assam. Key Words:- Bihu, Gosain Uliuwn, Bhaona. 1. Introduction : In the valley of the mighty river Brahmaputra in Assam, different groups of people of different ethnicity, culture, religion and following various customs and traditions began to live from the very ancient times. Some of them were autochthonous while others came across the Northern or the Eastern hill from the plains on the west as traders or pilgrims. -

Traditional Socio-Political Institutions of the Tiwas

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 4, Ver. II (Apr. 2016) PP 01-05 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Traditional Socio-Political Institutions of the Tiwas Lakhinanda Bordoloi Department of Political Science, Dhing College, Nagaon, Assam I. Introduction The Tiwas are concentrated mainly in the central plains of Assam covering the district of Nagaon, Morigaon and Kamrup. A section of the Tiwas lives in the hilly areas of Karbi Anglong, some villages are in the districts like Jorhat, Lakhimpur and Dhemaji of the state of Assam of and Ri-bhoi district of eastern part of the state of Meghalaya. The Tiwas, other than hills, foothill and some remote/isolated areas don‟t know to speak in their own language. A rapid cultural change has been observed among the Tiwas living in the plains. It is also revealed that, the process of social change occurred in traditional socio-cultural practices in a unique direction and places have formed sub-culture. In the areas- Amri and Duar Amla Mauza of Karbi Anglong, Mayong parts in the state of Meghalaya, villages of foothill areas like Amsoi, Silsang, Nellie, Jagiroad, Dimoria, Kathiatoli, Kaki (Khanggi); the villages like Theregaon near Howraghat, Ghilani, Bhaksong Mindaimari etc are known for the existence of Tiwa language, culture and tradition. In the Pasorajya and Satorajya, where the plain Tiwas are concentrating become the losing ground of traditional socio-political, cultural institutions, practices and the way of life. The King and the Council of Ministers: Before the advent of Britishers the Tiwas had principalities that enjoyed sovereign political powers in the area. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

Critically Assessing Traditions: the Case of Meghalaya

Working Paper no.52 CRITICALLY ASSESSING TRADITIONS: THE CASE OF MEGHALAYA Manorama Sharma NEIDS (Shillong, India) November 2004 Copyright © Manorama Sharma, 2004 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Development Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Programme Critically Assessing Traditions: The Case of Meghalaya1 Manorama Sharma NEIDS (Shillong, India) It could be cogently argued ...that in Meghalaya, there are not two but three competing systems of authority – each of which is seeking to ‘serve’ or represent the same constituency. The result has been confusion and confrontation especially at the local level on a number of issues.2 This observation by the experts of the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution reflects the present crisis of governance in the North East Indian state of Meghalaya. In fact, the main tussle for power and control over resources seems to be between the tribal organisations that have been designated by the Constitution of India as ‘traditional institutions’, and the constitutionally elected bodies. -

Working Through Partition: Making a Living in the Bengal Borderlandsã

IRSH 46 (2001), pp. 393±421 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859001000256 # 2001 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Working Through Partition: Making a Living in the Bengal Borderlandsà Willem van Schendel Summary: Partition, the break-up of colonial India in 1947, has been the subject of considerable serious historical research, but almost exclusively from two distinctive perspectives: as a macropolitical event; or as a cultural and personal disaster. Remarkably, very little is known about the socioeconomic impact of Partition on different localities and individuals. This exploratory essay considers how Partition affected working people's livelihood and labour relations. The essay focuses on the northeastern part of the subcontinent, where Partition created an international border separating East Bengal ± which became East Pakistan, then Bangladesh ± from West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, and other regions which joined the new state of India. Based largely on evidence contained in ``low-level'' state records, the author explores how labour relations for several categories of workers in the new borderland changed during the period of the late 1940s and 1950s. In the Indian subcontinent, the word ``Partition'' conjures up a particular landscape of knowledge and emotion. The break-up of colonial India has been presented from vantage points which privilege certain vistas of the postcolonial landscape. The high politics of the break-up itself, the violence and major population movements, and the long shadows which Partition cast over the relationship between India and Pakistan (and, from 1971, Bangladesh) have been topics of much myth-making, intense polemics, and considerable serious historical research. As three rival nationalisms were being built on con¯icting interpretations of Partition, most analysts and historians have been drawn towards the study of Partition as a macropolitical event. -

THE TIWA, AUTONOMOUS Councrl (ELECTTON) R.ULES, 2005

I- THE TIWA, AUTONOMOUS couNCrL (ELECTTON) R.ULES, 2005 w@qq q{& Assam State Election Com'emnission Dispur, Guwahati-78[CI06 2015 \ GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR DEPARTMENT FOR WELFARE OF PLAIN TRIBES & BACKWARD CLASSES NOTIFICATION The 7th December, 2005 No. TAD/BC/295105/6 : \n exercise of powers coiferred by section 60 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council Act, 1995 (Assam Act XXV of 1995), the Governor of Assam is hereby pleased to make the following rules regulating the matters relating to the Elections to the General Council namely : PART-I Preliminary Short title and 1. (1) These rules may be called the Tiwa Autonomous Council Commencement (Election) Rules, 2005. (2) They shall come into force on the date of their publication in the Official Gazette. Definitions 2. In these rules unless the context otheriwise requires, (a) "Act" means the TIWA AUTONOMOUS COUNCIL ACT, 1995. (b) "Authority" means an Authority appointed by the Government. from time to time, by notification in the Official Gazette. to try an election petition under Sub-Section (l) of 59 of the Acr: (c) "Ballot Box" means and includes any box, bag or other receptacle used for the insertion of ballot paper by voters during polll (d) "Commission" means the Assam State Election Commission: (e) "Constitution" means the Constitution of India. (0 "Constituency" means a Constituency notified by the Government by an order made under Section 48 of the Act for the purpose of election to the General Council; (g) "Comrpr practice" means any of the practices specified in Section 123 of the Representation of people Act. -

Social Change and Development

Vol. XVI No.1, 2019 Social Change and Development Social Change and Development A JOURNAL OF OKD INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT Vol. XVI No.1 January 2019 CONTENTS Editorial Note i Articles Citizens of the World but Non-Citizens of the State: The Curious Case of Stateless People with Reference to International Refugee Law Kajori Bhatnagar 1-15 The Paradox of Autonomy in the Darjeeling Hills: A Perception Based Analysis on Autonomy Aspirations Biswanath Saha, Gorky Chakraborty 16-32 BJP and Coalition Politics: Strategic Alliances in the States of Northeast Shubhrajeet Konwer 33-50 A Study of Sub-National Finance with Reference to Mizoram State in Northeast Vanlalchhawna 51-72 MGNREGS in North Eastern States of India: An Efficiency Analysis Using Data Envelopment Analysis Pritam Bose, Indraneel Bhowmik 73-89 Tribal Politics in Assam: From line system to language problem Juri Baruah 90-100 A Situational Analysis of Multidimensional Poverty for the North Eastern States of India using Household Level Data Niranjan Debnath, Salim Shah 101-129 Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan: Findings from an Empirical Analysis Monjit Borthakur, Joydeep Baruah 130-144 Book Review Monastic Order: An Alternate State Regime Anisha Bordoloi 145-149 ©OKDISCD 153 Social Change and Development Vol. XVI No.1, 2019 Editorial Note For long, discussions on India’s North East seem to have revolved around three issues viz. immigration, autonomy and economic underdevelopment. Though a considerable body of literature tend to deal with the three issues separately, yet innate interconnections among them are also acknowledged and often discussed. The region has received streams of immigrants since colonial times. -

Laheramtiwacasemarkersfinal.Pdf

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 14:1 January 2014 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Case Markers in Tiwa Language: A Brief Study Laheram Muchahary, Ph.D. Research Scholar =========================================================== Abstract Case is an important category of grammar. It is an inflected form of noun and pronoun which is used to show the relationship among different words used in a sentence. The present paper investigates the case marker in Tiwa language spoken in Assam. In this language, case is realized by the addition of case ending used as post positions. Therefore, they are called postpositional phrases. Postpositional phrases are made up of a noun phrase followed by post position. 1. Introduction The North-eastern region is known for its diversity as different tribes live in this region for centuries together. This region of India is bounded by the political boundary of China in the north, Bhutan in the west, Burma in the east and Bangladesh Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 14:1 January 2014 Laheram Muchahary, Ph.D. Research Scholar Case Markers in Tiwa Language: A Brief Study 220 in the south. It is comprised of eight states and they are Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikhim and Tripura. -

Entomophagy with Special Reference to Assam Hridisha Nandana Hazarika, Faculty, Department of Zoology, Raha College, Nagaon, Assam, India, [email protected]

International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM) ISSN : 2454-9150 Vol-04, Issue-04, July 2018 Entomophagy with Special Reference to Assam Hridisha Nandana Hazarika, Faculty, Department Of Zoology, Raha College, Nagaon, Assam, India, [email protected] Abstract: Edible insects are natural renewable source that provides food to many ethnic groups in Assam. The paper explored the traditional knowledge related to the practice of eating different insects as food. Practice of entomophagy is quite common among the ethnic peoples of Assam especially among the tribes of Dhemaji, Morigaon, Udalguri and Karbi anglong districts. The ethnic people consume these insects as their regular diet or during special occasions. The edible insects have high nutritional value and they are rich in nutrients especially in proteins, suggesting their use as good dietary supplements of balanced diet. Keywords: Edible insects, North-east India, Assam, Nutrition, Tradition, Culture. I. INTRODUCTION %), Hemiptera (17 %), Hymenoptera (10 %), Odonata (8 %), Lepidoptera (4 %) and Isoptera (2 %) [6]. The native The word entomophagy is derived from Greek work people inhabiting in the north-eastern states of India “entomon” meaning insect and “phagein” meaning to eat. consume edible insect species at their different Entomophagy literally means consumption of insects by developmental stages. These people use their traditional human as their food. The vast diversity of habitats of insect wisdom to determine which species to be eaten at what species that serve as traditional foods presents an almost stage. However, they agree that insects must be healthy and never-ending diversity of situations in which recognition should be processed immediately. However the ethnic tribes and progressive management of the food insect resource of this region eat insects both immature as well as adult can result not only in better human nutrition but stages. -

The Pattern of Flow and Utilisation of Funds by the Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council in Assam

EVALUATION STUDY ON THE PATTERN OF FLOW AND UTILISATION OF FUNDS BY THE KARBI ANGLONG AUTONOMOUS COUNCIL IN ASSAM Sponsored by the Planning Commission Govt. of India K.P. KUMARAN NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT NORTH EASTERN REGIONAL CENTRE NIRD LANE NH-37 JAWAHARNAGAR, KHANAPARA GUWAHATI – 781 022 2003 2 CONTENTS Chapter Title Page I INTRODUCTION 1-7 • Methodology • Study Area • Karbi Anglong • Population • BPL Family • Economy II STRUCTURE OF THE DISTRICT COUNCIL : 8-14 ADMINISTRATIVE SET UP AND DELIVERY MECHANISM • Official Body • Elected Body • Legislative Powers • Executive Powers • Financial Powers • Village Committee • Flow of fund and delivery mechanism III REVENUE GENERATED AND FLOW OF FUND TO THE 15-31 COUNCIL • Revenue generated by the council • Pattern of allocation and utilization of grant in Aid • Allocation of grant in aid: Sector Wise • Sector wise allocation (Distribution of plan + non plan funds) IV FLOW OF GRANT IN AID TO THE SECTORAL 32-42 DEVELOPMENTS AND ITS UTILIZATION • Departments under production sector • Departments under social sector • Departments under infrastructure sector • Problems encountered by the sectoral departments V IMPLEMENTATION OF DEVELOPMENT SCHEMES BY 43-50 THE SECTORAL DEPARTMENT • Community based scheme • Individual oriented scheme • Beneficiary oriented scheme • Scheme relating to training • Summary and Conclusion 3 VI SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 51-62 • Structure of the District council and delivery mechanism • Flow of fund and delivery mechanism • Revenue generated by the council • Patterns of allocation and utilization of grant in Aid • Flow of grant in Aid to sectoral department and its utilisation • Implementation of development schemes by sectoral departments • Recommendations LIST OF TABLES Sl.No Title of the Tables Page no.