Socio-Political Development of Surma Barak Valley from 5 to 13 Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Had Conducted a Study “Flood Damage Mitigation Measures

Report on the outcome of the Workshop Held on 14th June, 2016 To discuss on the findings of the study titled ‘Flood Damage Mitigation Measure for Barak Valley In South Assam including effects of Climate Change’ 1. Introduction: Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) had conducted a study “Flood Damage Mitigation Measures for Barak Valley in South Assam, including Effects of Climate Change” in collaboration with National Institute of Technology, Silchar. Moreover NIT, Silchar had partnered with IIT, Guwahati for undertaking the climate change componentfor the project. The final report of the study was submitted in the year 2014. The report comprised of study findings along with suggestions, short and long term for flood mitigation measures in Barak Valley. To take forward the study findings, the executive summery along with short and long term solutions were submitted to the concerned Departments viz. Water Resources Department, Soil Conservation Deptt, Agriculture Department, Department of Environment, Forest & Climate Change and Inland Water Transport Department for taking necessary action. To review and understand the actions taken by concerned department in this regard, ASDMA organized a half-day workshop on 14th June, 2016 at ASDMA Conference Hall where the finding of the study were presented by Prof P.S. Choudhry, Civil Engineering Department, NIT, Silchar and also discussed suggestions regarding the implementation of the same.ASDMA also presented regarding the short & long-term goals and highlighted department-wise modalities in its implementation. The workshop was attended by 34 officials from various concerned departments and participated in the group discussion held to take stock of the actions taken and explore the strategy for future planning that would be helpful towards mitigation of flood in Barak valley. -

Name Designation NIC Email Ids Shri Vinod Kumar Pipersenia Chief

Name Designation NIC Email ids Shri Vinod Kumar Pipersenia Chief Secretary and Resident Representative, Assam Bhawan, New Delhi, Assam [email protected], [email protected] Shri Bhaskar Mushahary Addl Chief Secretary, Cultural Affairs and Information & Public Relations Deptts., Assam [email protected] Shri Subhash Chandra Das Addl Chief Secretary, Revenue & Disaster Management, Public Health Engineering, Personnel, Pension [email protected] & Public Grievances and AR & Training Deptts., Assam Shri Ram Tirath Jindal Addl Chief Secretary, Industries & Commerce, Mines & Minerals and Handloom, Textiles & Sericulture [email protected] Deptts. & MD, Assam Hydrocarbon & Energy Ltd Rajiv Kumar Bora Addl Chief Secretary, WPT & BC and Soil Conservation Deptts. and Chairman, SLNA (IWMP), Assam [email protected] Shri V. B. Pyarelal Addl Chief Secretary, Power (E), Agriculture, Panchayat & Rural Dev Deptts. and Agruculture [email protected] Production Commissioner, Assam Shri Shyam Lal Mewara Addl Chief Secretary, Transport, Public Enterprises, Labour & Employment and Tea Tribes Welfare [email protected] Deptts., Assam Shri Davinder Kumar Addl Chief Secretary, Environment & Forest and Water Resorces Deptts., Asssam [email protected] Shri V. S. Bhaskar Addl Chief Secretary, Tourism and IT Deptts., Assam [email protected] Shri M. G. V. K. Bhanu Addl Chief Secretary to CM and Addl Chief Secretary, Home, Political, SAD, GAD and Health & [email protected] Family Welfare Deptts., Assam Dr. Ajay Kumar Singh Principal Secretary, Parliamentary Affairs, Minorities Welfare & Dev and Implementation of Assam [email protected] Accrod Deptts, Assam Jayashree Daolagupu Principal Secretary, Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council [email protected] Shri Sameer Kumar Khare Principal Secretary, Finance Deptt. -

Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley During Medieval Period Dr

প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo ISSN 2278-5264 প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo An Online Journal of Humanities & Social Science Published by: Dept. of Bengali Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Website: www.thecho.in Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley during Medieval Period Dr. Sahabuddin Ahmed Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam Email: [email protected] Abstract After the fall of Srihattarajya in 12 th century CE, marked the beginning of the medieval history of Barak-Surma Valley. The political phenomena changed the entire infrastructure of the region. But the socio-cultural changes which occurred are not the result of the political phenomena, some extra forces might be alive that brought the region to undergo changes. By the advent of the Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal, a qualitative change was brought in the region. This historical event caused the extension of the grip of Bengal Sultanate over the region. Owing to political phenomena, the upper valley and lower valley may differ during the period but the socio- economic and cultural history bear testimony to the fact that both the regions were inhabited by the same people with a common heritage. And thus when the British annexed the valley in two phases, the region found no difficulty in adjusting with the new situation. Keywords: Homogeneity, aryanisation, autonomy. The geographical area that forms the Barak- what Nihar Ranjan Roy prefers in his Surma valley, extends over a region now Bangalir Itihas (3rd edition, Vol.-I, 1980, divided between India and Bangladesh. The Calcutta). Indian portion of the region is now In addition to geographical location popularly known as Barak Valley, covering this appellation bears a historical the geographical area of the modern districts significance. -

1Edieval Assam

.-.':'-, CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION : Historical Background of ~1edieval Assam. (1) Political Conditions of Assam in the fir~t half of the thirt- eenth Century : During the early part of the thirteenth Century Kamrup was a big and flourishing kingdom'w.ith Kamrupnagar in the· North Guwahat.i as the Capital. 1 This kingdom fell due to repeated f'.1uslim invasions and Consequent! y forces of political destabili t.y set in. In the first decade of the thirteenth century Munammedan 2 intrusions began. 11 The expedition of --1205-06 A.D. under Muhammad Bin-Bukhtiyar proved a disastrous failure. Kamrtipa rose to the occasion and dealt a heavy blow to the I"'!Uslim expeditionary force. In 1227 A.D. Ghiyasuddin Iwaz entered the Brahmaputra valley to meet with similar reverse and had to hurry back to Gaur. Nasiruddin is said to have over-thrown the I<~rupa King, placed a successor to the throne on promise of an annual tribute. and retired from Kamrupa". 3 During the middle of the thirteenth century the prosperous Kamrup kingdom broke up into Kamata Kingdom, Kachari 1. (a) Choudhury,P.C.,The History of Civilisation of the people of-Assam to the twelfth Cen tury A.D.,Third Ed.,Guwahati,1987,ppe244-45. (b) Barua, K. L. ,·Early History of :Kama r;upa, Second Ed.,Guwahati, 1966, p.127 2. Ibid. p. 135. 3. l3asu, U.K.,Assam in the l\hom J:... ge, Calcutta, 1 1970, p.12. ··,· ·..... ·. '.' ' ,- l '' '.· 2 Kingdom., Ahom Kingdom., J:ayantiya kingdom and the chutiya kingdom. TheAhom, Kachari and Jayantiya kingdoms continued to exist till ' ' the British annexation: but the kingdoms of Kamata and Chutiya came to decay by- the turn of the sixteenth century~ · . -

Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 61 The NEHU Journal, Vol XII, No. 2, July - December 2014, pp. 61-76 Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam BINAYAK DUTTA * Abstract Political history of Partition of India in 1947 is well-documented by historians. However, the grass root politics and and the ‘victim- hood’ of a number of communities affected by the Partition are still not fully explored. The scholarly moves to write alternative History based on individual memory and family experience, aided by the technological revolution have opened up multiple narratives of the partition of Assam and its aftermath. Here in northeast India the Partition is not just a History, but a lived story, which registers its presence in contemporary politics through songs, poems, rhymes and anecdotes related to transfer of power in Assam. These have remained hidden from mainstream partition scholarship. This paper seeks to attempt an anecdotal history of the partition in Assam and the Sylhet Referendum, which was a part of this Partition process . Keywords : sylhet, partition, referendum, muslim league, congress. Introduction HVSLWHWKHSDVVDJHRIPRUHWKDQVL[W\¿YH\HDUVVLQFHWKHSDUWLWLRQ of India, the politics that Partition generated continues to be Dalive in Assam even today. Although the partition continues to be relevant to Assam to this day, it remains a marginally researched area within India’s Partition historiography. In recent years there have been some attempts to engage with it 1, but the study of the Sylhet Referendum, the event around which partition in Assam was constructed, has primarily been treated from the perspective of political history and refugee studies. 2 ,W LV WLPH +LVWRU\ ZULWLQJ PRYHG EH\RQG WKH FRQ¿QHV RI political history. -

Decline of Hindus and the Rise of Muslims in Assam

Decline of Hindus and the Rise of Muslims in Assam In view of the special attention that is focused now on Assam because of the ongoing assembly elections, we are once again deviating from the proper sequence to discuss the religious demography of Assam in this note. In the normal course, after describing the unusually high growth in the intensely Muslim pocket of Mewat in Haryana, we should have taken up the much larger pocket of high Muslim presence and growth in western Uttar Pradesh, which borders on Haryana and Delhi. Instead we shall discuss Assam and West Bengal in this and the next note and return to Western UP and other pockets of high Muslim presence and growth later. The relative growth of Muslims in Assam during 2001-11 has been extraordinarily high. The share of Muslims in the population of the State has risen by 3.3 percentage points in this decade. This is the highest accretion in the Muslim share for any State; the average accretion for India has been only 0.8 percentage points. This is also the highest accretion in the share of Muslims witnessed in Assam in any decade since Independence. Muslims now form a large majority in seven districts of the Brahmaputra valley, Dhubri, Goalpara, Bongaigaon, Barpeta, Darrang, Nagaon and Morigaon; and, in two of the three districts of Barak valley, Hailakandi and Karimganj. In eight sub-districts of the former region, Muslim presence is above 90 percent and in another 6 it is between 80 and 90 percent. This level of dominance of a community in an area indicates not only that their relative growth is higher, but also that others are being excluded from there. -

Unit 23 Central and Eastern India

.UNIT 23 CENTRAL AND EASTERN INDIA Objectives Introduction Malwa Jaunpur Bengal Assam 23.5.1 Kamata-Kamrup 23.5.2 The Ahoms Orissa Let Us sum UP Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 4 23.0 OBJECTIVES In the present Unit, we will study about regional states in Central and Eastern India during the 13-15th centuries. After reading this Unit, you would learn about: the emergence of regional states in Central and Eastern India, territorial expansion of these regional kingdoms, their relations with their neighbours and other regional states, and 1 their relations with the Delhi Sultanate. 23.4 INTRODUCTION You have already read (in Block 5, Unit 18) that regional kingdoms posed severe threat to the already weakened Delhi Sultanate and with their emergence began the process of the physical disintegration of the Sultanate. In this Unit, our focus would be on the emergence of regional states in Central and Eastern India viz., Malwa, Jaunpur, Bengal, Assam and Orissa. We will study the polity-establishment, expansion and disintegration-of the above kingdoms. You would know how they emerged and succeeded in establishing their hegemony. During the 13th-15th centuries in Central and Eastern India, there emerged two types of kingdoms: a) those whose rise and development was independent of the Sultanate (for example : the kingdoms of Assam and Orissa) and b) Bengal, Malwa and Jaunpur who owed tHeir existencr ru the Sultanate. All these kingdoms were constantlyat war with each other. The nobles, ci,' ;s or rajas and local aristocracy played crucial roles in these confrontations. 23.2 MALWA The decline of the Sultanate paved the way for the emergence bf the independent kingdom of Malwa. -

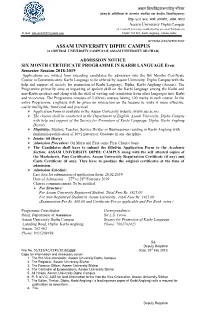

Assam University Diphu Campus (A Central University Established by an Act of Parliament) E-Mail: [email protected] Diphu-782 462, Karbi Anglong, Assam, India

असम वि�िवि饍यालय दिफू परिसि (संसि के अधिनियम के अꅍत셍गत थावपत एक केꅍरीय वि�िवि饍यालय) दिफू - ७८२ ४६२, कार्बी आं셍लⴂ셍, असम, भाित Assam University Diphu Campus (A Central University established by an act of Parliament) E-mail: [email protected] Diphu-782 462, Karbi Anglong, Assam, India BY EMAIL/FAX/SPEED POST ASSAM UNIVERSITY DIPHU CAMPUS (A CRNTRAL UNIVERSITY CAMPUS OF ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR) ADMISSION NOTICE SIX MONTH CERTIFICATE PROGRAMME IN KARBI LANGUAGE Even Semester Session 2018-2019 Applications are invited from intending candidates for admission into the Six Months Certificate Course in Communicative Karbi Language to be offered by Assam University, Diphu Campus with the help and support of society for promotion of Karbi Language, Diphu, Karbi Anglong (Assam). The Programme primarily aims at imparting of spoken skill on the Karbi language among the Karbi and non-Karbi speakers and along with the skill of writing and translation from other languages into Karbi and vice-versa. The Programme consists of 3 (three) courses having 100 marks in each course. In the entire Programme, emphasis will be given on interaction on the lessons to make it more effective, easily intelligible, functional and practical. Application Form is available in the Assam University website (www.aus.ac.in). The classes shall be conducted at the Department of English, Assam University, Diphu Campus with help and support of the Society for Promotion of Karbi Language, Diphu, Karbi Anglong District. Eligibility: Student, Teacher, Service Holder or Businessmen residing in Karbi Anglong with minimum qualification of 10+2 pattern or Graduate in any discipline. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Conservation of Gangetic Dolphin in Brahmaputra River System, India

CONSERVATION OF GANGETIC DOLPHIN IN BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER SYSTEM, INDIA Final Technical Report A. Wakid Project Leader, Gangetic Dolphin Conservation Project Assam, India Email: [email protected] 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There was no comprehensive data on the conservation status of Gangetic dolphin in Brahmaputra river system for last 12 years. Therefore, it was very important to undertake a detail study on the species from the conservation point of view in the entire river system within Assam, based on which site and factor specific conservation actions would be worthwhile. However, getting the sponsorship to conduct this task in a huge geographical area of about 56,000 sq. km. itself was a great problem. The support from the BP Conservation Programme (BPCP) and the Rufford Small Grant for Nature Conservation (RSG) made it possible for me. I am hereby expressing my sincere thanks to both of these Funding Agencies for their great support to save this endangered species. Besides their enormous workload, Marianne Dunn, Dalgen Robyn, Kate Stoke and Jaimye Bartake of BPCP spent a lot of time for my Project and for me through advise, network and capacity building, which helped me in successful completion of this project. I am very much grateful to all of them. Josh Cole, the Programme Manager of RSG encouraged me through his visit to my field area in April, 2005. I am thankful to him for this encouragement. Simon Mickleburgh and Dr. Martin Fisher (Flora & Fauna International), Rosey Travellan (Tropical Biology Association), Gill Braulik (IUCN), Brian Smith (IUCN), Rundall Reeves (IUCN), Dr. A. R. Rahmani (BNHS), Prof. -

The Insecure World of the Nation

The Insecure World of the Nation Ranabir Samaddar In The Marginal Nation, which dealt with transborder migration from Bangladesh to West Bengal, two moods, two mentalities, and two worlds were in description – that of cartographic anxiety and an ironic unconcern. In that description of marginality, where nations, borders, boundaries, communities, and the political societies were enmeshed in making a nonnationalised world, and the citizenmigrant (two animals yet at the same time one) formed the political subject of this universe of transcendence, interconnections and linkages were the priority theme. Clearly, though conflict was an underlying strain throughout the book, the emphasis was on the human condition of the subject the migrant’s capacity to transgress the various boundaries set in place by nationformation in South Asia. Therefore, responding to the debate on the numbers of illegal migrants I termed it as a “numbers game”. My argument was that in this world of edges, the problem was not what was truth (about nationality, identity, and numbers), but truth (of nationality, identity, and numbers) itself was the problem.1 Yet, this was an excessively humanised description, that today on hindsight after the passing of some years since its publication, seems to have downplayed the overwhelming factor of conflict and wars that take place because “communities must be defended” – one can say the “permanent condition” in which communities find themselves. On this rereading of the problematic the questions, which crop up are: