Behavioral Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Member Magazine of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology CONTENTS

Vol. 13 / No. 5 / May 2014 THE MEMBER MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY CONTENTS NEWS FEATURES PERSPECTIVES 2 14 18 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE PROPAGATING POSSIBILITIES OPEN LETTER Good reads and the power of data Researcher tinkers with tree genetics On hindsight and gratitude 5 19 NEWS FROM THE HILL PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Making scientic research 11 19 Tips for Ruth L. Kirschstein training a priority for Congress grant applicants 21 e skills you need for 6 a career in science policy MEMBER UPDATE 22 Give credit where it is due ACS honors nine ASBMB members 24 7 EDUCATION JOURNAL NEWS 24 Reimagining the undergraduate 18 science course 12 27 ‘Creativity is in all – not a possession ASBMB NEWS of only a certain few’ 2014 annual meeting travel award winners 28 OUTREACH Yale Science Diplomats 28 31 LIPID NEWS Desperately seeking Sputnik for fundamental science 32 OPEN CHANNELS Reader comments 14 12 In our cover story, we learn about one research team’s eort to manipulate common trees to produce high-value commodities. MAY 2014 ASBMB TODAY 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE calibration curves are much worse. tomy for breast cancer by surgeon perpetually changing landscape of is is particularly true for the local William Halsted and the implications breast cancer was beginning to tire THE MEMBER MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY television forecasts: ey substantially of studies of its eectiveness. Moving him out. Trials, tables, and charts FOR BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY Good reads and overpredict the probability of rain. past surgical treatments that focused had never been his forte; he was a is tendency gets at a key point. -

Robert A. Alberty 1921–2014

Robert A. Alberty 1921–2014 A Biographical Memoir by Gordon G. Hammes and Carl Frieden ©2014 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. ROBERT ARNOLD ALBERTY June 21, 1921–January 18, 2014 Elected to the NAS, 1965 Robert A. Alberty maintained an enthusiasm for science throughout his entire life. His presence at meetings was easily detectable, as he was blessed with an unmistak- able and booming voice that conveyed his latest scien- tific interests and above all his continual commitment to the science enterprise. Alberty directed this passion to thermodynamics and kinetics in particular, especially as applied to biological systems, and his research in these areas established a rich legacy for modern biophysical chemistry. He was a “triple-threat” scientist, excelling not only in research but also in teaching and university administration. Alberty (Bob to all who knew him) was born in Winfield, By Gordon G. Hammes Kansas, but when he was five years old his family moved and Carl Frieden to Lincoln, Nebraska. Even as a boy, he displayed a strong interest in science, exemplified by a basement chemistry laboratory and photographic dark room that he built in the family’s home. When he entered the University of Nebraska in 1939, Alberty had been planning a career as a chemical engineer, but then he discovered that this would require extensive coursework in drafting and surveying. Because he had already learned surveying from his grandfather, he saw no need to take college courses in the subject. -

Newsletter University of Wisconsin-Madison

NEWSLETTER UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON For friends of the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Table of Contents From the Chair .............................................................. 3 Gene Regulation .....................................................20-21 Exciting Discoveries ...................................................4-6 In Memoriam ..............................................................21 Biochemistry Phase II ...................................................7 Remembering Ross Inman ..........................................22 Kamaluddin Ahmad Graduate Scholarship ...................8 RNA Maxi Group ........................................................23 Student Faculty Liaison Committee ..............................9 Department Alumnus: Dustin Maly ............................ 24 After Retirement - Bill Reznikoff .................................10 Department Alumnus: Jenifer (Bork) Miskowski ....... 25 New Faculty Profi le .....................................................11 Biochemistry Graduate Degrees .............................26-29 Celebrating Har Gobind Khorana ..........................12-13 Staff Departures ..........................................................30 Our Department in India .......................................14-15 From the Labs ........................................................31-53 Our Department in Uganda ........................................16 Contact Information ...................................................54 iGEM -

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C. Gunsalus 1912 Born in South Dakota, son of Irwin Clyde and Anna Shea Gunsalus 1935 B.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1937 M.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940 Ph.D. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940-44 Assistant Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1944-46 Associate Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1946-47 Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1947-50 Professor of Bacteriology, Indiana University 1949 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1950-55 Professor of Microbiology, University of Illinois 1955-82 Professor of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1955-66 Head of Division of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1959 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1959-60 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1962 Patent granted for lipoic acid 1965- Member of National Academy of Sciences 1968 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1972-76 Member Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1977-78 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1973-75 President of Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1978-81 Chairman of National Academy of Sciences, Section of Biochemistry 1982- Professor of Biochemistry, Emeritus, University of Illinois 1984 Honorary Doctorate, Indiana University 15/5/40 2 Box Contents List Box Contents Box Number Biographical and Personal Biographical Materials, 1967-1995 1 Personal Finances, 1961-65 1-2 Publications, Studies and Reports Journals and Reports, 1955-68 -

Wilfred A. Van Der Donk

WILFRED A. VAN DER DONK University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Department of Chemistry, 161 RAL Box 38-5 Urbana, IL 61801 Phone: (217) 244-5360; FAX: (217) 244-8533 [email protected] Date of birth April 21, 1966 US citizen since 2013 EDUCATION 1989 B.Sc & M.Sc, Leiden University, The Netherlands Thesis Advisor: Prof. Jan Reedijk Thesis Title: Model Complexes for Copper Metallo-Enzymes 1994 Ph.D., Rice University, Houston, Texas Thesis Advisor: Prof. Kevin Burgess Thesis Title: Transition Metal Catalyzed Hydroborations POSITIONS SINCE FINAL DEGREE 1994-1997 Postdoctoral Fellow, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA Advisor Prof. JoAnne Stubbe Project: Mechanistic Studies on Ribonucleotide Reductase 1997-2003 Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2003-2005 Associate Professor, Department of Chemistry University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2005-2008 William H. and Janet Lycan Professor of Chemistry University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2008-present Richard E. Heckert Endowed Chair in Chemistry University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2008-present Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute 2007-present Professor, Institute for Genomic Biology University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS 1989 Cum Laude Masters Thesis, Leiden University 1989-1993 Robert A. Welch Predoctoral Fellowship 1991, 1994 Harry B. Weiser Scholarship for Excellence in Research (Rice University) 1994-1997 Postdoctoral Fellowship, Jane Coffin Childs Foundation for Medical Research 1997 Camille and Henry Dreyfus New Faculty Award 1998 Burroughs Wellcome New Investigator in the Pharmacological Sciences 1998 Research Innovation Award from the Research Corporation 1 1999 School of Chemical Sciences Teaching Award (U. Illinois) 1999 UIUC Research Board Beckman Award 1999 Arnold and Mabel Beckman Young Investigator Award 1999 3M Non-Tenured Faculty Award 2000 Cottrell Scholar of the Research Corporation 2001 Beckman Fellow, Center for Advanced Study, University of Illinois 2001 Alfred P. -

Editors' Statement on Considerations of Biodefence and Biosecurity

EDITORIAL Editors’ statement on considerations of biodefence and biosecurity The threat of bioterrorism requires active consideration by scientists. On 9 January 2003, the US National Academy of Sciences held a discussion on the balance between scientific openness and security. The next day, a group of editors met to discuss the issues with specific reference to the scientific publication process. The following statement has emerged from that meeting. The principles dis- cussed will be considered and followed through by Nature Medicine The process of scientific publication, is a view, shared by nearly all, that there is FOURTH: We recognize that on occasions through which new findings are reviewed information that, although we cannot an editor may conclude that the potential for quality and then presented to the rest now capture it with lists or definitions, harm of publication outweighs the poten- of the scientific community and the pub- presents enough risk of use by terrorists tial societal benefits. Under such circum- lic, is a vital element in our national life. that it should not be published. How and stances, the paper should be modified, or New discoveries reported in research pa- by what processes it might be identified not be published. Scientific information is pers have helped improve the human con- will continue to challenge us, because – as also communicated by other means: semi- dition in myriad ways: protecting public all present acknowledged — it is also true nars, meetings, electronic posting, etc. health, multiplying agricultural yields, that open publication brings benefits not Journals and scientific societies can play fostering technological development and only to public health but also in efforts to an important role in encouraging investi- economic growth, and enhancing global combat terrorism. -

Medical School .Book

bulletin of Duke University 2003-2004 School of Medicine The Mission of Duke University James B. Duke’s founding Indenture of Duke University directed the members of the University to “provide real leadership in the educational world” by choosing indi- viduals of “outstanding character, ability and vision” to serve as its officers, trustees and faculty; by carefully selecting students of “character, determination and application;” and by pursuing those areas of teaching and scholarship that would “most help to de- velop our resources, increase our wisdom, and promote human happiness.” To these ends, the mission of Duke University is to provide a superior liberal educa- tion to undergraduate students, attending not only to their intellectual growth but also to their development as adults committed to high ethical standards and full participa- tion as leaders in their communities; to prepare future members of the learned profes- sions for lives of skilled and ethical service by providing excellent graduate and professional education; to advance the frontiers of knowledge and contribute boldly to the international community of scholarship; to promote an intellectual environment built on a commitment to free and open inquiry; to help those who suffer, cure disease and promote health, through sophisticated medical research and thoughtful patient care; to provide wide ranging educational opportunities, on and beyond our campuses, for traditional students, active professionals and life-long learners using the power of in- formation technologies; and to promote a deep appreciation for the range of human dif- ference and potential, a sense of the obligations and rewards of citizenship, and a commitment to learning, freedom and truth. -

Table of Contents University of Rochester Department of Chemistry 404 Hutchison Hall RC Box 270216 Chemistry Department Faculty and Staff Rochester, NY 14627-0216 3

CONTACT ADDRESS Table of Contents University of Rochester Department of Chemistry 404 Hutchison Hall RC Box 270216 Chemistry Department Faculty and Staff Rochester, NY 14627-0216 3 PHONE 4 Letter from the Chair (585) 275-4231 6 Donors to the Chemistry Department EMAIL 10 Alumni News [email protected] Esther M. Conwell receives National Medal of Science WEBSITE 14 http://www.chem.rochester.edu 16 A Celebration in Honor of Richard Eisenberg 18 Department Mourns the Loss of Jack Kampmeier CREDITS 20 Xiaowei Zhuang receives the 2010 Magomedov- EDITOR Shcherbinina Award Lory Hedges 21 Joseph DeSimone receives for 2011 Harrison Howe LAYOUT & DESIGN EDITOR John Bertola (B.A. ’09, M.S. ’10W) Award Lory Hedges 22 Chemistry Welcomes Michael Neidig REVIEWING EDITORS Kirstin Campbell 23 New Organic Chemistry Lab Lynda McGarry Terrell Samoriski 24 The 2011 Biological Chemistry Cluster Retreat Barb Snaith 26 Student Awards and Accolades COVER ART AND LOGOS Faculty News Breanna Eng (’13) 28 Sheridan Vincent 60 Faculty Publications WRITING CONTRIBUTIONS 66 Commencement 2011 Department Faculty Lory Hedges 68 Commencement Awards Breanna Eng (’13) Terri Clark 69 Postdoctoral Fellows and Research Associates Select Alumni 70 Seminars and Colloquia PHOTOGRAPHS UR Communications 74 Staff News National Science & Technology Departmental Funds Medals Foundation 79 John Bertola (B.A. ’09, M.S. ’10W) 80 Alumni Update Form Karen Chiang Ria Casartelli Sheridan Vincent Thomas Krugh 1 2 Faculty and Staff FACULTY RESEARCH PROFESSORS BUSINESS OFFICE Esther M. Conwell Anna Kuitems PROFESSORS OF Samir Farid Randi Shaw CHEMISTRY Diane Visiko Robert K. Boeckman, Jr. SENIOR SCIENTISTS Doris Wheeler Kara L. -

Small and Broken Type in Tables AVAILABLE Fromcommission on Human Resources, Rational Research Council, 2101 Constitution Aven N.V., Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 138 475 SE 022 497 TITLE Personnel Needs and Training for Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The 1976 Report of the ComMittee on a, Studi of National Needs for Biomedical and Behavioral Research Personnel. INSTITUTION National Academy of Sciences - National Research Conncil, Washington, D.C. Commission on Human Resources. SPONS AGENCY National Institntes of Health (DHEW), Bethesda, Md. .PUB DATE 76 CONTRACT NO-1-0D-5-2109 NOTE 243p.; For 1975 Report, see ED 114 009; Contains small and broken type in Tables AVAILABLE FROMCommission on Human Resources, Rational Research Council, 2101 Constitution Aven N.V., Washington, D.C. 20418 (free) EDRS,PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$12.71 Plus Postage. 1)ZSCRIPTORS *Behavioral Science Research; *College Science; Doctoral Programs; Enrollment Trends; *Government Role; *Higher Education; *Manpower Needs; Manpower Utilization; Medical Edncation; Research; *Sciences; Surveys ABSTRACT This report is the second of the annual reports prepared by this Committee. The Zommittee addressed itself in-this report primarily to what it viewed as the most pressing issue - making recommendations for the number of individuals uho should be supported by the research trainingsprograms of the National Institutes of Health and the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration during fiscal years 1977 and 1978 in each of four broad fields: basic medical sciences, behavioral sciences, clinical sciences, and health services research. Chapter I presents an introduction and recommendation: Chapter II is a national overview of research training the biomedical and behavioral science,s. Chapter III is an assessment of manpower needs. Chapter IV considers future directions; included are four Areas the Cdmmittee_believes-need further attention. -

Visit the National Academies Press Online, the Authoritative Source For

Policy Implications of International Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars in the United States Commitee on Policy Implications of International Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Scholars in the United States, Board on Higher Education and Workforce, National Research Council ISBN: 0-309-54940-X, 196 pages, 6 x 9, (2005) This free PDF was downloaded from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11289.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online, free • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books • Purchase PDFs • Explore with our innovative research tools Thank you for downloading this free PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll-free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This free book plus thousands more books are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the Web address of the online, full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires -

SUMMER2014.Pdf

Discover More Molecular Structures and Interactions Nano ITC Nano DSC Protein – Protein Interactions Protein Structural Domains and Stability • Prioritize Drug Candidate Target • Excipient Influence on Molecular Stability Interactions • Stability of Biopharmaceuticals • Validate Ligand Binding to • Direct Measure of Molecular Nucleic Acid Thermodynamics • Quantify both Enthalpy and Entropy in One Titration • No labeling or immobilization required www.tainstruments.com ACA Structure Matters Summer 2014 ACA HOME PAGE: www.amercrystalassn.org Table of Contents 2 President’s Column What’s on the Cover 3 ACA Balance Sheet - page 40 4 News from Canada 4-5 2015 ACA Awards 5 Buerger Award to Greg Petsko 5 Warren Award to Laurence Marks 6 Etter Early Career to Yan Jessie Zhang 6-8 General News and Awards Update on the ACA History Portal 10 YSSIG News & Views 11-12 100,000th structure deposited to the wwPDB 13-16 Structural Dynamics - Editor’s Picks 17 Puzzle Corner 18 Obituary - Gary Newton (1928-2014) 19-23 ACA Living History - Ned Seeman 24-25 2014 Class of ACA Fellows 26-27 Book Reviews 28-30 Joint Mid-Atlantic Macro / SER-CAT Symposium 32-38 Candidates for ACA Officers and Committees for 2015 39 What’s on the Cover 40-41 Harmonius Balance for Public Access 42 ACA Corporate Members 43 2014 ACA Meeting Sponsors and Exhibitors 44-45 2014 Travel Awards / Photos from Albuquerque 46-47 2015 ACA Meeting Preview 48 Future Meetings Contributors to this Issue AIP Fellowship Opportunities ACA RefleXions staff: Editor: Thomas Koetzle [email protected] Please address matters pertaining to ads, membeship, or use of Editor: Judith L. -

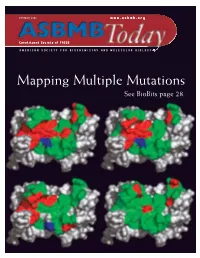

Mapping Multiple Mutations See Biobits Page 28

OCTOBER 2006 www.asbmb.org Constituent Society of FASEB AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY Mapping Multiple Mutations See BioBits page 28. Why Choose 21 st Century Biochemicals For Custom Peptides and Antibodies? “…the dual phosphospecific antibody you “…of the 15 custom antibodies we ordered from your company, 13 worked. “…our in-house QC lab confirmed the Thanks for the great work!” high purity of the peptide.” Over 70 years combined experience manufacturing peptides and anti- bodies Put our expertise to work for you in a collaborative atmosphere The Pinnacle – Affinity Purified Antibodies >85% Success Rate! Peptide Sequencing Included for 100% Guaranteed Peptide Fidelity Complete 2 rabbit protocol with PhD technical support and $ 1675 epitope design ◆ From HPLC purified peptide to affinity purified antibody with no hidden charges!..........$1895 Special pricing through December 3 1, 2006 Phosphospecific Antibody Experts ◆ Custom Phosphospecific Ab’s as low as $2395 Come speak with our scientists at Neuroscience in Atlanta, GA - Booth 2127 and HUPO in Long Beach, CA - Booth 231 www.21stcenturybio.com 33 Locke Drive, Marlboro, MA 01752 Made in the P: 508.303.8222 Toll-free: 877.217.8238 U.S.A. F: 508.303.8333 E: [email protected] www.asbmb.org AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OCTOBER 2006 Volume 5, Issue 7 features 8 Osaka Bioscience Institute: A World Leader in Scientific Research 11 JLR Looks at Systems Biology 12 Education and Professional Development ON THE COVER: Human growth hormone 14 Judith Klinman to Receive ASBMB-Merck Award residues colored by contribution to receptor 15 Scott Emr Selected for ASBMB-Avanti Award recognition: red, favorable; 16 The Chromosome Cycle green, neutral; blue, unfavorable.