The Boreal Below Mining Issues and Activities in Canada’S Boreal Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

023810 Rangifer Spec Issue

The Ninth North American Caribou Workshop, S7 Kuujjuaq, Québec, Canada, 23-27 April, 2001. Status, population fluctuations and ecological relationships of Peary caribou on the Queen Elizabeth Islands: Implications for their survival Frank L. Miller1 & Anne Gunn2 1 Canadian Wildlife Service, Prairie & Northern Region, Room 200, 4999 - 98th. Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T6B 2X3 Canada ([email protected]). 2 Department of Resources, Wildlife and Economic Development, Government of the Northwest Territories, Box 1320, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories X1A 3S8 Canada. Abstract: The Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) was recognized as 'Threatened' by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada in 1979 and 'Endangered' in 1991. It is the only member of the deer family (Cervidae) found on the Queen Elizabeth Islands (QEI) of the Canadian High Arctic. The Peary caribou is a significant part of the region's biodiversity and a socially important and economically valuable part of Arctic Canada's natural heritage. Recent microsatellite DNA findings indicate that Peary caribou on the QEI are distinct from caribou on the other Arctic Islands beyond the QEI, including Banks Island. This fact must be kept in mind if any translocation of caribou to the QEI is pro• posed. The subspecies is too gross a level at which to recognize the considerable diversity that exists between Peary cari¬ bou on the QEI and divergent caribou on other Canadian Arctic Islands. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada should take this considerable diversity among these caribou at below the subspecies classification to mind when assigning conservation divisions (units) to caribou on the Canadian Arctic Islands. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

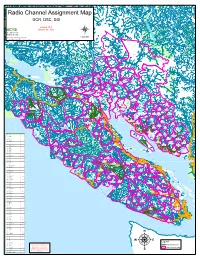

Bcts Dcr, Dsc

Radio Channel Assignment Map DCR, DSC, DSI Version 10.8 BCTS January 30, 2015 BC Timber Sales W a d d i Strait of Georgia n g t o n G l a 1:400,000 c Date Saved: 2/3/2015 9:55:56 AM i S e c r a r Path: F:\tsg_root\GIS_Workspace\Mike\Radio_Frequency\Radio Frequency_2015.mxd C r e e k KLATTASINE BARB HO WARD A A T H K O l MTN H O M l LANDMAR K a i r r C e t l e a n R CAMBRIDG E t e R Wh i E C V A r I W R K A 7 HIDD EN W E J I C E F I E L D Homathko r C A IE R HEAK E T STANTON PLATEAU A G w r H B T TEAQ UAHAN U O S H N A UA Q A E 8 T H B R O I M Southgate S H T N O K A P CUMSACK O H GALLEO N GUNS IGHT R A E AQ V R E I T R r R I C V E R R MT E H V a RALEIG H SAWT rb S tan I t R o l R A u e E HO USE r o B R i y l I l V B E S E i 4 s i R h t h o 17 S p r O G a c l e Bear U FA LCO N T H G A Stafford R T E R E V D I I R c R SMIT H O e PEAK F Bear a KETA B l l F A T SIR FRANCIS DRAKE C S r MT 2 ke E LILLO OE T La P L rd P fo A af St Mellersh Creek PEAKS TO LO r R GRANITE C E T ST J OHN V MTN I I V E R R 12 R TAHUMMING R E F P i A l R Bute East PORTAL E e A L D S R r A E D PEAK O O A S I F R O T T Glendale 11 R T PRATT S N O N 3 S E O M P Phillip I I T Apple River T O L A B L R T H A I I SIRE NIA E U H V 11 ke Po M L i P E La so M K n C ne C R I N re N L w r ro ek G t B I OSMINGTO N I e e Call Inlet m 28 R l o r T e n T E I I k C Orford V R E l 18 V E a l 31 Toba I R C L R Fullmore 5 HEYDON R h R o George 30 Orford River I Burnt Mtn 16 I M V 12 V MATILPI Browne E GEORGE RIVER E R Bute West R H Brem 13 ke Bute East La G 26 don ey m H r l l e U R -

3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36

DFO - L bra y MPOBibio heque II 1 111111 11 11 11 V I 1 120235441 3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36 Some If:eat/viz& 3,5,unamia, Olt the Yacific ettadt of South and ✓ cuith anwitica, T. S. Murty, S. 0. Wigen and R. Chawla Marine Sciences Directorate 975 Department of the Environment, Ottawa Marine Sciences Directorate Manuscript. Report Series No. 36 SOME FEATURES OF TSUNAMIS ON THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AND NORTH AM ERICA . 5 . Molly S . O. Wigen and R. Chawla 1975 Published by Publie par Environment Environnement Canada Canada I' Fisheries and Service des !Aches Marine Service et des sciences de la mer Office of the Editor Bureau du fiedacteur 116 Lisgar, Ottawa K1 A Of13 1 Preface This paper is to be published in Spanish in the Proceedings of the Tsunami Committee XVII Meeting, Lima, Peru 20-31 Aug. 1973, under the International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth Interior. 2 Table of Contents Page Abstract - Resume 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Resonance characteristics of sonic inlets on the Pacific Coast of Soulh and North America 13 3. Secondary undulations 25 4. Tsunami forerunner 33 5. Initial withdrawal of water 33 6. Conclusions 35 7. References 37 3 4 i Abstract In order to investigate the response of inlets to tsunamis, the resonance characteristics of some inlets on the coast of Chile have been deduced through simple analytical considerations. A comparison is made with the inlets of southeast Alaska, the mainland coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. It is shown that the general level of intensif yy of secondary undulations is highest for Vancouver Island inlets, and least for those of Chile and Alaska. -

Copyright (C) Queen's Printer, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

B.C. Reg. 38/2016 O.C. 112/2016 Deposited February 29, 2016 effective February 29, 2016 Water Sustainability Act WATER DISTRICTS REGULATION Note: Check the Cumulative Regulation Bulletin 2015 and 2016 for any non-consolidated amendments to this regulation that may be in effect. Water districts 1 British Columbia is divided into the water districts named and described in the Schedule. Schedule Water Districts Alberni Water District That part of Vancouver Island together with adjacent islands lying southwest of a line commencing at the northwest corner of Fractional Township 42, Rupert Land District, being a point on the natural boundary of Fisherman Bay; thence in a general southeasterly direction along the southwesterly boundaries of the watersheds of Dakota Creek, Laura Creek, Stranby River, Nahwitti River, Quatse River, Keogh River, Cluxewe River and Nimpkish River to the southeasterly boundary of the watershed of Nimpkish River; thence in a general northeasterly direction along the southeasterly boundary of the watershed of Nimpkish River to the southerly boundary of the watershed of Salmon River; thence in a general easterly direction along the southerly boundary of the watershed of Salmon River to the southwesterly boundary thereof; thence in a general southeasterly direction along the southwesterly boundaries of the watersheds of Salmon River and Campbell River to the southerly boundary of the watershed of Campbell River; thence in a general easterly direction along the southerly boundaries of the watersheds of Campbell River and -

ASSESSMENT REPORT of WORK DONE on the HEMLO PROPERTY, THUNDER BAY MINING DISTRICT ONTARIO, CANADA, 2007 and 2008; April 2009; Assessment Report

ASSESSMENT REPORT OF WORK DONE ON THE HEMLO PROPERTY CLAIM 4214923 THUNDER BAY MINING DISTRICT ONTARIO CANADA 2011 September 15, 2011 GeoVector Management Inc. on behalf of Kaminak Gold Corporation . Joseph W. Campbell, P.Geo. Roman Tykajlo, P.Geo. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents 2 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Property Description and Location 4 3.0 Access 8 4.0 Previous Work 9 5.0 Geological Setting 11 5.1 Regional Geology 11 6.0 2011 Exploration 11 7.0 Recommendations 12 8.0 References 12 9.0 Statement of Qualifications 13 10.0 Statement of Expenditures -Till Sample Survey Costs Summary 15 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1a Hemlo North Project Location 5 Figure 1b Hemlo North Project Location Close-up 6 Figure 2 Kaminak Gold Claim Location – Hemlo North Project 7 - 2 - LIST OF TABLES Table 1 Mineral Claim Information 8 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix 1 Till Sample Locations and Descriptions 16 Appendix 2 Overburden Drilling Management Limited Gold Grain KIM 18 and MMSIM Results on Tills Appendix 3 ACTLABS Analytical Certificates of Till Sample Analyses 27 Appendix 4 List of Personnel 35 LIST OF MAPS Map 1 Till Sample Survey, Locations and Results. 1:2500scale Back Pocket - 3 - 1.0 INTRODUCTION – KAMINAK HEMLO PROPERTY In 2007, Kaminak Gold Corporation developed an exploration play in the Hemlo area that focused on determining possible shear controls on known gold mineralization, and postulating possible extensions of the known trend, and parallel trends. Review of historical work showed that extensive exploration had been done in the target areas, particularly in the early and mid 1980s after the initial Hemlo discovery and staking rush, but also during the mid to late 1990s as the camp matured. -

Original Field Data and Traverse Notes Must Be Provided by the Licensee

Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development Minister’s Office MEMORANDUM Cliff: 259440 Ref: 280-20 November 25, 2020 To: Sharon Hadway, Regional Executive Director, West Coast Allan Johnsrude, Regional Executive Director, South Coast From: The Honourable Doug Donaldson Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development Re: New Coast Appraisal Manual I hereby approve the new Coast Appraisal Manual and attach a copy for your use. The manual is available at the following link: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/competitive-forest-industry/ timber-pricing/coast-timber-pricing/coast-appraisal-manual-and-amendments This manual will come into force on December 15, 2020. Further amendments or revisions to this manual require my approval. Minister pc: Melissa Sanderson, Assistant Deputy Minister, Forest Policy and Indigenous Relations Division Jim Schafthuizen, Executive Director, Forest Policy and Indigenous Relations Division Allan Bennett, Director, Timber Pricing Branch TIMBER PRICING BRANCH Coast Appraisal Manual Effective December 15, 2020 This manual is intended for the use of individuals or companies when conducting business with the British Columbia Government. Permission is granted to reproduce it for such purposes. This manual and related documentation and publications, are protected under the Federal Copyright Act. They may not be reproduced for sale or for other purposes without the express written permission of the Province of British Columbia. Coast Appraisal Manual Highlights New Coast Appraisal Manual Highlights The new Coast Appraisal Manual includes clarification to policy, an update to the market pricing system, and an update of the tenure obligation adjustments and specified operations for December 15, 2020 onward. -

Falconbridge Limited 2003 Annual Report FUNDAMENTAL STRENGTH Our Operations

Falconbridge Limited 2003 Annual Report FUNDAMENTAL STRENGTH Our Operations NICKEL COPPER CORPORATE 1 Sudbury 6 Compañía Minera Doña Inés de 9 Corporate Office (Sudbury, Ontario) Collahuasi S.C.M. (44%) (Toronto, Ontario) Mines and mills nickel-copper ores; smelts (Northern Chile) 10 Project Offices nickel-copper concentrate from Sudbury’s Mines and mills copper sulphide ores into (Kone and Nouméa, New Caledonia; mines and from Raglan, and processes concentrate; mines and leaches copper Brisbane, Australia) custom feed materials. oxide ores to produce cathodes. 11 Exploration Offices 2 Raglan 7 Kidd Division (Sudbury, Timmins and Toronto, Ontario; (Nunavik, Quebec) (Timmins, Ontario) Laval, Quebec; Pretoria, South Africa; Mines and mills nickel-copper ores from Mines copper-zinc ores from the Kidd Mine. Belo Horizonte, Brazil; Brisbane, open pits and an underground mine. Mills, smelts and refines copper-zinc ores Australia) from the Kidd Mine and processes Sudbury 3 Nikkelverk A/S copper concentrate and custom feed 12 Business Development (Kristiansand, Norway) materials. (Toronto, Ontario) Refines nickel, copper, cobalt, precious and platinum group metals from Sudbury, 8 Compañía Minera Falconbridge 13 Marketing and Sales Raglan and from custom feeds. Lomas Bayas (Brussels, Belgium; Pittsburgh, (Northern Chile) Pennsylvania; Tokyo, Japan) 4 Falconbridge Dominicana, C. por A. Mines copper oxide ores from an open pit; (85.26%) (Bonao, Dominican Republic) refines into copper cathode through the 14 Technology Centre Mines, mills, smelts -

Final Complete Dissertation Kua 1

Trends and Ontology of Artistic Practices of the Dorset Culture 800 BC - 1300 AD Hardenberg, Mari Publication date: 2013 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Hardenberg, M. (2013). Trends and Ontology of Artistic Practices of the Dorset Culture 800 BC - 1300 AD. København: Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 08. Apr. 2020 Trends and Ontology of Artistic Practices of the Dorset Culture 800 BC – 1300 AD Volume 1 By © Mari Hardenberg A Dissertation Submitted to the Ph.d.- School In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy SAXO-Institute, Department of Prehistoric Archaeology, Faculty of Humanities University of Copenhagen August 2013 Copenhagen Denmark ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the various artistic carvings produced by the hunter-gatherer Dorset people who occupied the eastern Arctic and temperate regions of Canada and Greenland between circa BC 800 – AD 1300. It includes considerations on how the carved objects affected and played a role in Dorset social life. To consider the role of people, things and other beings that may be said to play as actors in interdependent entanglements of actions, the agency/actor- network theory is employed. From this theoretical review an interpretation of social life as created by the ways people interact with the material world is presented. This framework is employed as a lens into the social role and meaning the carvings played in the Dorset society. The examined assemblages were recovered from a series of Dorset settlement sites, mainly in house, midden, and burial contexts, providing a substantive case study through which variations and themes of carvings are studied. -

Carte Des Zones Contrôlées Controlled Area

280 RY LAKE 391 MYSTE Nelson House Pukatawagan THOMPSON 6 375 Sherridon Oxford House Northern Manitoba ds River 394 Nord du GMo anitoba 393 Snow Lake Wabowden 392 6 0 25 50 75 100 395 398 FLIN FLON Kilometres/kilomètres Lynn Lake 291 397 Herb Lake 391 Gods Lake 373 South Indian Lake 396 392 10 Bakers Narrows Fox Mine Herb Lake Landing 493 Sherritt Junction 39 Cross Lake 290 39 6 Cranberry Portage Leaf Rapids 280 Gillam 596 374 39 Jenpeg 10 Wekusko Split Lake Simonhouse 280 391 Red Sucker Lake Cormorant Nelson House THOMPSON Wanless 287 6 6 373 Root Lake ST ST 10 WOODLANDS CKWOOD RO ANDREWS CLEMENTS Rossville 322 287 Waasagomach Ladywood 4 Norway House 9 Winnipeg and Area 508 n Hill Argyle 323 8 Garde 323 320 Island Lake WinnBRiOpKEeNHEgAD et ses environs St. Theresa Point 435 SELKIRK 0 5 10 15 20 East Selkirk 283 289 THE PAS 67 212 l Stonewall Kilometres/Kilomètres Cromwel Warren 9A 384 283 509 KELSEY 10 67 204 322 Moose Lake 230 Warren Landing 7 Freshford Tyndall 236 282 6 44 Stony Mountain 410 Lockport Garson ur 220 Beausejo 321 Westray Grosse Isle 321 9 WEST ST ROSSER PAUL 321 27 238 206 6 202 212 8 59 Hazelglen Cedar 204 EAST ST Cooks Creek PAUL 221 409 220 Lac SPRINGFIELD Rosser Birds Hill 213 Hazelridge 221 Winnipeg ST FRANÇOIS 101 XAVIER Oakbank Lake 334 101 60 10 190 Grand Rapids Big Black River 27 HEADINGLEY 207 St. François Xavier Overflowing River CARTIER 425 Dugald Eas 15 Vivian terville Anola 1 Dacotah WINNIPEG Headingley 206 327 241 12 Lake 6 Winnipegosis 427 Red Deer L ake 60 100 Denbeigh Point 334 Ostenfeld 424 Westgate 1 Barrows Powell Na Springstein 100 tional Mills E 3 TACH ONALD Baden MACD 77 MOUNTAIN 483 300 Oak Bluff Pelican Ra Lake pids Grande 2 Pointe 10 207 eviève Mafeking 6 Ste-Gen Lac Winnipeg 334 Lorette 200 59 Dufresne Winnipegosis 405 Bellsite Ile des Chênes 207 3 RITCHOT 330 STE ANNE 247 75 1 La Salle 206 12 Novra St. -

Hail the Columbia III

Hail the Columbia III Toronto , Ontario , Canada Friday, June 20, 2008 TO VANCOUVER AND BEYOND: About a year earlier, my brother Peter and his wife Lynn, reported on a one-of-a-kind cruise adventure they had in the Queen Charlotte Strait area on the inside passage waters of British Columbia. Hearing the stories and seeing the pictures with which they came back moved us to hope that a repeat voyage could be organized. And so we found ourselves this day on a WestJet 737 heading for Vancouver. A brief preamble will help set the scene: In 1966 Peter and Lynn departed the civilization of St. Clair Avenue in Toronto, for the native community of Alert Bay, on Cormorant Island in the Queen Charlotte Strait about 190 miles, as the crow flies, north-west of Vancouver. Peter was a freshly minted minister in the United Church of Canada and an airplane pilot of some experience. The United Church had both a church and a float-equipped airplane in Alert Bay. A perfect match. The purpose of the airplane was to allow the minister to fly to the something over 150 logging camps and fishing villages that are within a couple hundred miles of Alert Bay and there to do whatever it is that ministers do. This was called Mission Service. At the same time the Anglican Church, seeing no need to get any closer to God than they already were, decided to stay on the surface of the earth and so Horseshoe Bay chugged the same waters in a perky little ship. -

Infonorth Five Hundred Meetings of the Arctic Circle

ARCTIC VOL. 67, NO. 2 (JUNE 2014) P. 1 – 12 InfoNorth Five Hundred Meetings of the Arctic Circle by C.R. Burn SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES 1 AND 2 TABLE 1. List of meetings of the Arctic Circle.1 Special Meetings are in bold. Year Meeting Date Speaker2 Topic3 1947 1 12 December Flt. Lt. A.H. Tinker Establishment of weather stations at Eureka and Resolute Bay 1948 2 15 January Sgt. F.S. Farrar, RCMP Film: St Roch 3 16 February R.G. Madill, Flt. Lt. J.F. Drake North magnetic pole 4 18 March Lt. Col. A. Croft Operation Musk-ox 5 13 April H.M. Raup Botany, geology, and archaeology, Alaska Highway 6 25 May J.G. Wright Film: RMS Nascopie 7 20 August Picnic at the Jenness’s cottage 8 4 November C.S. Lord Mining in NWT 9 9 December P. Serson Operation Magnetic 1949 10 13 January B.J. Woodruff Geodetic Survey of Canada 11 10 February P.D. Baird Project Snow Cornice 12 10 March Cdr. D.C. Nutt, USNR Antarctica 13 14 April J.C. Wyatt Construction in the Arctic 14 12 May Mrs. T.H. Manning Travels in Hudson Bay and Foxe Basin 15 10 November Dr. J.C. Callaghan Experiences of a medical officer in the Arctic 16 8 December M.J. Dunbar Marine resources of the eastern Arctic 1950 17 12 January Flt. Lt. B. Hartman Search and rescue in the eastern Arctic 18 9 February A.E. Porsild Plant life 19 9 March D. Wilkinson NFB in the North 20 13 April T.H.