Hail the Columbia III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia Immerse yourself in the living Traditions Indigenous travel experiences have the power to move you. To help you feel connected to something bigger than yourself. To leave you changed forever, through cultural exploration and learning. Let your true nature run free and be forever transformed by the stories and songs from the world’s most diverse assembly of living Indigenous cultures. #IndigenousBC | IndigenousBC.com Places To Go CARIBOO CHILCOTIN COAST KOOTENAY ROCKIES NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TŜILHQOT’IN | TSE’KHENE | DANE-ZAA | ST̓ÁT̓IMCETS KTUNAXA | SECWEPEMCSTIN | NSYILXCƏN SM̓ALGYA̱X | NISG̱A’A | GITSENIMX̱ | DALKEH | WITSUWIT’EN SECWEPEMCSTIN | NŁEʔKEPMXCÍN | NSYILXCƏN | NUXALK NEDUT’EN | DANEZĀGÉ’ | TĀŁTĀN | DENE K’E | X̱AAYDA KIL The Ktunaxa have inhabited the rugged area around X̱AAD KIL The fjordic coast town of Bella Coola, where the Pacific the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers on the west side of Ocean meets mighty rainforests and unmatched Canada’s Rockies for more than 10 000 years. Visitors Many distinct Indigenous people, including the Nisga’a, wildlife viewing opportunities, is home to the Nuxalk to the snowy mountains of Creston and Cranbrook Haida and the Tahltan, occupy the unique landscapes of people and the region’s easternmost point. The continue to seek the adventure this dramatic landscape Northern BC. Indigenous people co-manage and protect Cariboo Chilcotin Coast spans the lower middle of offers. Experience traditional rejuvenation: soak in hot this untamed expanse–more than half of the size of the BC and continues toward mountainous Tsilhqot’in mineral waters, view Bighorn Sheep, and traverse five province–with a world-class system of parks and reserves Territory, where wild horses run. -

Klahoose First Nation Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Klahoose First Nation Community Wildfire Protection Plan Submitted to: Tina Wesley Emergency Program Coordinator Klahoose First Nation Ph: 250 935-6536 Submitted by: Email: [email protected] B.A. Blackwell & Associates Ltd. Shaun Koopman 270 – 18 Gostick Place Protective Services Coordinator North Vancouver, BC, V7M 3G3 Strathcona Regional District Ph: 604-986-8346 990 Cedar Street Email: [email protected] Campbell River, BC, V9W 7Z8 Ph: 250-830-6702 Email: [email protected] B.A. Blackwell & Associates Ltd. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank the following Klahoose First Nation and Strathcona Regional District staff: Tina Wesley, Klahoose First Nation Fisheries Officer and Emergency Program Coordinator, and Shaun Koopman, Strathcona Regional District Protective Services Coordinator. These individuals invested substantial time in meetings, answering questions, reviewing and commenting on the contents of this document, or providing information. In addition, the authors would like to thank staff from the BC Wildfire Service, including: Paul Bondoc (Wildfire Technician, Powell River Centre), Tony Botica (Fuel Management Specialist, Powell River Centre), and Dana Hicks (Fuel Management Specialist); staff from the Cortes Forest General Partnership (CFGP): Mark Lombard (Operations Manager), as well as staff from the Cortes Island Firefighting Association (CIFFA): Mac Diver (Fire Chief) and Eli McKenty (Fire Captain). This report would not be possible without the Union of British Columbia Municipalities (UBCM) Community Resiliency Investment (CRI) Program, First Nations’ Emergency Services Society (FNESS), and funding from the Province of British Columbia. ˚Cover photo Merrick Architecture- Klahoose First Nation Multipurpose Building. Accessed from http://merrickarch.com/work/klahoose-multi-centre May 17, 2021 Klahoose First Nation Wildfire Protection Plan 2020 ii B.A. -

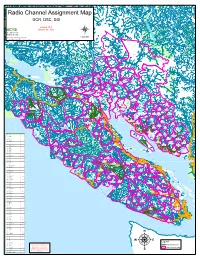

Bcts Dcr, Dsc

Radio Channel Assignment Map DCR, DSC, DSI Version 10.8 BCTS January 30, 2015 BC Timber Sales W a d d i Strait of Georgia n g t o n G l a 1:400,000 c Date Saved: 2/3/2015 9:55:56 AM i S e c r a r Path: F:\tsg_root\GIS_Workspace\Mike\Radio_Frequency\Radio Frequency_2015.mxd C r e e k KLATTASINE BARB HO WARD A A T H K O l MTN H O M l LANDMAR K a i r r C e t l e a n R CAMBRIDG E t e R Wh i E C V A r I W R K A 7 HIDD EN W E J I C E F I E L D Homathko r C A IE R HEAK E T STANTON PLATEAU A G w r H B T TEAQ UAHAN U O S H N A UA Q A E 8 T H B R O I M Southgate S H T N O K A P CUMSACK O H GALLEO N GUNS IGHT R A E AQ V R E I T R r R I C V E R R MT E H V a RALEIG H SAWT rb S tan I t R o l R A u e E HO USE r o B R i y l I l V B E S E i 4 s i R h t h o 17 S p r O G a c l e Bear U FA LCO N T H G A Stafford R T E R E V D I I R c R SMIT H O e PEAK F Bear a KETA B l l F A T SIR FRANCIS DRAKE C S r MT 2 ke E LILLO OE T La P L rd P fo A af St Mellersh Creek PEAKS TO LO r R GRANITE C E T ST J OHN V MTN I I V E R R 12 R TAHUMMING R E F P i A l R Bute East PORTAL E e A L D S R r A E D PEAK O O A S I F R O T T Glendale 11 R T PRATT S N O N 3 S E O M P Phillip I I T Apple River T O L A B L R T H A I I SIRE NIA E U H V 11 ke Po M L i P E La so M K n C ne C R I N re N L w r ro ek G t B I OSMINGTO N I e e Call Inlet m 28 R l o r T e n T E I I k C Orford V R E l 18 V E a l 31 Toba I R C L R Fullmore 5 HEYDON R h R o George 30 Orford River I Burnt Mtn 16 I M V 12 V MATILPI Browne E GEORGE RIVER E R Bute West R H Brem 13 ke Bute East La G 26 don ey m H r l l e U R -

3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36

DFO - L bra y MPOBibio heque II 1 111111 11 11 11 V I 1 120235441 3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36 Some If:eat/viz& 3,5,unamia, Olt the Yacific ettadt of South and ✓ cuith anwitica, T. S. Murty, S. 0. Wigen and R. Chawla Marine Sciences Directorate 975 Department of the Environment, Ottawa Marine Sciences Directorate Manuscript. Report Series No. 36 SOME FEATURES OF TSUNAMIS ON THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AND NORTH AM ERICA . 5 . Molly S . O. Wigen and R. Chawla 1975 Published by Publie par Environment Environnement Canada Canada I' Fisheries and Service des !Aches Marine Service et des sciences de la mer Office of the Editor Bureau du fiedacteur 116 Lisgar, Ottawa K1 A Of13 1 Preface This paper is to be published in Spanish in the Proceedings of the Tsunami Committee XVII Meeting, Lima, Peru 20-31 Aug. 1973, under the International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth Interior. 2 Table of Contents Page Abstract - Resume 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Resonance characteristics of sonic inlets on the Pacific Coast of Soulh and North America 13 3. Secondary undulations 25 4. Tsunami forerunner 33 5. Initial withdrawal of water 33 6. Conclusions 35 7. References 37 3 4 i Abstract In order to investigate the response of inlets to tsunamis, the resonance characteristics of some inlets on the coast of Chile have been deduced through simple analytical considerations. A comparison is made with the inlets of southeast Alaska, the mainland coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. It is shown that the general level of intensif yy of secondary undulations is highest for Vancouver Island inlets, and least for those of Chile and Alaska. -

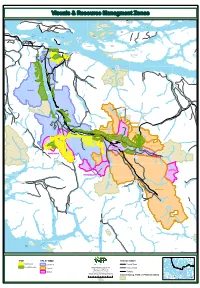

Visuals & Resource Managment Zones

Visuals & Resource Managment Zones Port Elizabeth Trinity G I L F O R D I S L A N D Bay BROUGHTON ARCHIPELAGO Single Tree CONSERVANCY Pt. SUQUASH Lady Islands BROUGHTON ARCHIPELAGO Knight Inlet Sointula MARINE " PARK Mitchell Village Bay Island BROUGHTON Swanson CORMORANT CHANNEL Island Ledge Pt. CORMORANT Cluxewe STRAIT CHANNEL Port McNeill Harbour MARINE Turnour Island PARK Port McNeill Alert Bay " " Clio Channel Harbledown Island Flagstaff Is. Hanson Island WHITE DUCK LAKE Telegraph Cove " LOWER NIMPKISH Beaver Cove QWIQUALLAAQ/BOAT West Cracroft Island PARK BAY CONSERVANCY Cub Lake J O H N S T O N E ROBSON BIGHT (MICHAEL Robson BIGG) ECOLOGICAL Bight RESERVE LOWER TSITIKA RIVER PARK TSITIKA MOUNT MOUNTAIN DERBY ECOLOGICAL ECOLOGICAL RESERVE RESERVE Nimpkish Nimpkish Lake Bonanza Lake Tsitika NIMPKISH Nimpkish LAKE " PARK CLAUDE ELLIOTT ECOLOGICAL RESERVE TSITIKA RIVER ECOLOGICAL MOUNT RESERVE ELLIOTT ECOLOGICAL RESERVE CROSS LAKE Woss-Vernon Highway 19 Woss-Vernon Tsitika Atluck Lake Woss " TAHSISH Woss-Vernon KWOIS PARK TSITIKA-WOSS SCHOEN LAKE PINDER-ATLUCK PARK Woss-Vernon Lower Schoen Klaklakama Lake TAHSISH Lake RIVER ECOLOGICAL RESERVE ARTLISH CAVES PARK Woss Lake SCHOEN- STRATHCONA Tahsish Inlet WOSS-ZEBELLOS . Moketas Island WOSS LAKE PARK NIMPKISH RIVER ECOLOGICAL Fair Harbour RESERVE " DIXIE COVE MARINE PARK Woss-Vernon Vernon Lake Zeballos " Zeballos Inlet Espinosa Inlet Tahsis " Port Eliza WEYMER CREEK PARK TAHSIS INLET Muchalat Lake GOLD MUCHALAT PARK CATALA ISLAND MARINE PARK Catala ESPERANZA INLET Island NUCHATLITZ PARK "" VQO TFL37 RMZ Transportation Sayward " Modification Enhanced Paved Road Partial Retention Tree Farm Licence 37 General Gravel Road " Management Plan 10 Woss Special Overview Map - Jan. -

Quadra Island Builds Seniors Housing

ISSUE 478 www.discoveryislander.ca JULY 16, 2010 Stakeholders gather at the Quadra Seniors Housing Project site with the two Program Officers Mary Crowley and Karen Johnson from the Ministry of Housing and Social Development (fifth and sixth from the left). Quadra Island Builds Seniors Housing The Quadra Island Seniors Housing Society has begun construction Development Permit allows a total of three duplexes (6 units) to be of affordable, duplex rental units, specifically designed for seniors, in built. The Coastal Community Credit Union has donated a substantial Quathiaski Cove. Until now, many seniors have been forced to move off grant through the Quadra Branch’s Legacy Fund. Many of the Quadra when they could no longer maintain their home and property. tradespeople working on this project will be donating a portion of their These independent living homes will allow seniors to continue to live in time. A unique fundraising strategy was used when the $1000 Club was and contribute to their community. established - thirty six community members to date have joined this Thanks to a Job Creation Partnership with the Ministry of Housing special Seniors Housing Support Club. and Social Development sponsored by the Canada - British Columbia The Society would like to thank the Ministry of Housing and Social Labour Market Development Agreement, the Society expects to Development, the Strathcona Regional District, Coastal Community complete one duplex for low to moderate income seniors by this year Credit Union, the Royal Canadian Legion Branch 154, Quadra Island end. After many years of dedicated fundraising and volunteerism, Seniors Br.91 of BC O.A.P.O., the Real Estate Foundation of BC, Telus, the Quadra Island community is very happy to have received this Job and the community’s generous donors of cash and services. -

Heriot Bay Rd

Quadra Island Streets THE COMPLETE GUIDE (with maps) TO THE RESIDENTIAL STREETS & ROADS of QUADRA ISLAND,BC, in 2020 Including: Roads, Lanes, Ways, Places, Drives, Crescents etc., REVISED AND UPDATED EDITION, December 17th 2020 ISBN 978-1-927442-29-6 Canadian Catalogue of Publishing, Ottawa. Compiled by Quadra Island Community Members. Published on Quadra Island, BC, Canada, December, 2020. Quadra Island, pop. 3,000 British Columbia, BC, Canada Page 1 Index of Quadra Island Street Names, with their map reference in this street-map book. Index S treet Name Hint MAP No. Alder Place 5 runs off Cedar Drive Anderson Road 3 & 4 borders school’s west Animal Farm Road 5 runs off Heriot Bay Rd. Antler Road 6 runs off Cramer Rd. April Point Road 4 begins at Ferry Rd. Banning Road 8 Granite Bay Barton Road 5 runs off Milton Road Bold Point Road 8 & 9 runs past V.B. Lakes Breton Road 8 runs off Valdes Drive Buker Road 6 central Hooleyville Bull Road 6 runs off West Rd. Cape Mudge Road 1, 2 & 3 south end Quadra Cedar Drive 5 runs off Smith Road Cherrier Rd 9 runs off Conville Bay Rd. Chinook Cresent 2 runs off Upper Ridge Rd. Cliff Road 5 off end of Vaughn Road Conville Bay Road 9 runs off Bold Point Rd. Conville Point Road 9 near Main Lake Colter Road 3 runs off Helanton Road Cove Crescent 3 runs off Green Rd . Cramer Road 6 runs off West Rd . Page 2 STREET NAME MAP NO. HINT Cutter Road 6 runs off Hooley Rd. -

ARC174 Timberwest TFL47

Audit of Forest Planning and Practices TimberWest Forest Corporation Tree Farm Licence 47 FPB/ARC/174 February 2015 Table of Contents Audit Results ................................................................................................................................1 Background ................................................................................................................................1 Audit Approach and Scope .........................................................................................................2 Planning and Practices Examined ..............................................................................................2 Findings ......................................................................................................................................3 Audit Opinion ..............................................................................................................................5 Appendix 1: Forest Practices Board Compliance Audit Process ............................................6 Audit Results Background As part of the Forest Practices Board's 2014 compliance audit program, the Board randomly selected the Campbell River District as the location for a full scope compliance audit. Within the district, the Board selected Tree Farm Licence (TFL) 47, held by TimberWest Forest Corporation (TimberWest), for the audit. TFL 47 is located north of Campbell River, along Johnstone Strait, and southeast of Port McNeill. TimberWest’s activities were located in 12 forest development -

For Immediate Release 10-007 March 3, 2010 BC

For Immediate Release 10-007 March 3, 2010 BC FERRIES ANNOUNCES QUADRA AND CORTES ISLANDS SERVICE DURING TEMPORARY DOCK CLOSURE Quathiaski Cove terminal closed April 6 through 10 for construction VICTORIA – BC Ferries’ dock at Quathiaski Cove on Quadra Island will be temporarily closed for five days while a new berthing structure is installed. Alternate service will be provided for both Quadra and Cortes Islands during the dock closure from April 6 through 10, 2010. BC Ferries is making this significant investment at Quathiaski Cove to ensure continued safe, reliable service for years to come. The $5.3 million project includes the replacement of the ramp, pontoon, wingwalls and waiting shelter. While work on the project began at the beginning of February and will conclude at the end of April, BC Ferries has pre-fabricated the berthing structure and other components off-site to minimize the necessary dock closure period. During the closure the MV Tachek will operate between Campbell River and Heriot Bay terminal on Quadra Island, transporting commercial and essential vehicle traffic only. Beginning March 15, all customers will be required to reserve their desired sailing by calling 1-888-BC FERRY (1-888-223-3779). The MV Tenaka will operate between Campbell River and Whaletown terminal on Cortes Island. All vehicular and foot traffic are welcome and will be loaded on a first-come- first-serve basis. Both vessels will operate three round-trip voyages each day. In addition, a water taxi service will be available to transport foot passengers between Campbell River and Quathiaski Cove terminals. -

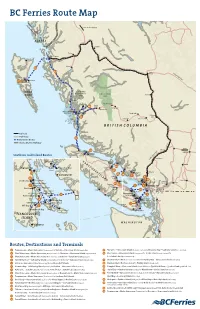

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2 2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2 2018 Annual Report About the SRD The Strathcona Regional District (SRD) is a partnership of five municipalities and four electoral areas, which covers approximately 22,000 square kilometers (8,517 square miles). The SRD serves and provides 44,671 residents (2016 census) with a diverse range of services including water and sewerage systems, fire protection, land use planning, parks, recreation and emergency response. The Strathcona Regional District was established on February 15, 2008, as a result of the provincial government’s restructure of the Comox Strathcona Regional District. The geography of the SRD ranges from forested hills, remote inlets, picturesque villages to vibrant urban landscapes. The borders extend from the Oyster River in the south to Gold River, Sayward, Tahsis, Zeballos and Kyuquot-Nootka in the north and west, and east to Cortes Island, Quadra Island and the Discovery Islands as well as a portion of the adjacent mainland north of Powell River. 128°0'0"W 127°0'0"W 126°0'0"W 125°0'0"W 124°0'0"W Stikine Fort Nelson-Liard Kitimat-Stikine er Peace River iv R o hk at m Skeena Buckley-Nechako o Queen Charlotte Fraser H Fort George 51°0'0"N Cariboo Central Coastal Columbia Q Shuswap u Thompson e Mount Waddington Nicola e Squamish North Lillooet Okanagan n Strathcona Powell Central East River Central Kootenay Kootenay Okanagan C Comox Hope Valley Sunshine Fraser Kootenay h Coast Valley Okanagan Boundary Greater Similkameen a Alberni Nanaimo Clayoquot Vancouver Island r Cowichan lo Valley t Capital 51°0'0"N -

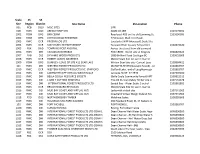

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale.