Compensation in Hazardous Facility Siting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

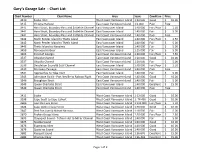

Gary's Charts

Gary’s Garage Sale - Chart List Chart Number Chart Name Area Scale Condition Price 3410 Sooke Inlet West Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3415 Victoria Harbour East Coast Vancouver Island 1:6 000 Poor Free 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3443 Thetis Island to Nanaimo East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3459 Nanoose Harbour East Vancouver Island 1:15 000 Fair $ 5.00 3463 Strait of Georgia East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 7.50 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Fair $ 5.00 3538 Desolation Sound & Sutil Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3539 Discovery Passage East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3541 Approaches to Toba Inlet East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3545 Johnstone Strait - Port Neville to Robson Bight East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Good $ 10.00 3546 Broughton Strait East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Excellent $ 15.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East -

Status and Distribution of Marine Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia

Status and Distribution of Marine Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Pete Davidson∗, Robert W Butler∗+, Andrew Couturier∗, Sandra Marquez∗ & Denis LePage∗ Final report to Parks Canada by ∗Bird Studies Canada and the +Pacific WildLife Foundation December 2010 Recommended citation: Davidson, P., R.W. Butler, A. Couturier, S. Marquez and D. Lepage. 2010. Status and Distribution of Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Bird Studies Canada & Pacific Wildlife Foundation unpublished report to Parks Canada. The data from this survey are publicly available for download at www.naturecounts.ca Bird Studies Canada British Columbia Program, Pacific Wildlife Research Centre, 5421 Robertson Road, Delta British Columbia, V4K 3N2. Canada. www.birdscanada.org Pacific Wildlife Foundation, Reed Point Marine Education Centre, Reed Point Marina, 850 Barnet Highway, Port Moody, British Columbia, V3H 1V6. Canada. www.pwlf.org Contents Executive Summary…………………..……………………………………………………………………………………………1 1. Introduction 1.1 Background and Context……………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 1.2 Previous Studies…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 2. Study Area and Methods 2.1 Study Area……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 2.2 Transect route……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 2.3 Kernel and Cluster Mapping Techniques……………………………………………………………………………..7 2.3.1 Kernel Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.3.2 Clustering Analysis………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.4 -

Technical Appendix B: System Description

TECHNICAL APPENDIX B: SYSTEM DESCRIPTION Assessment of Oil Spill Risk due to Potential Increased Vessel Traffic at Cherry Point, Washington Submitted by VTRA TEAM: Johan Rene van Dorp (GWU), John R. Harrald (GWU), Jason R.. W. Merrick (VCU) and Martha Grabowski (RPI) August 31, 2008 Vessel Traffic Risk Assessment (VTRA) - Final Report 08/31/08 TABLE OF CONTENTS B-1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................4 B-2. Waters of the Vessel Traffic Risk Assessment...................................................................4 B-2.1. Juan de Fuca-West:........................................................................................................4 B-2.2. Juan de Fuca-East:.........................................................................................................5 B-2.3. Puget Sound ...................................................................................................................5 B-2.4. Haro Strait-Boundary Pass...........................................................................................6 B-2.5. Rosario Strait..................................................................................................................6 B-2.6. Cherry Point...................................................................................................................6 B-2.7. SaddleBag........................................................................................................................7 -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

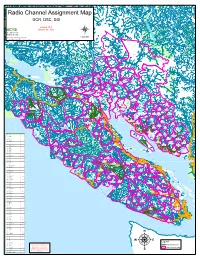

Bcts Dcr, Dsc

Radio Channel Assignment Map DCR, DSC, DSI Version 10.8 BCTS January 30, 2015 BC Timber Sales W a d d i Strait of Georgia n g t o n G l a 1:400,000 c Date Saved: 2/3/2015 9:55:56 AM i S e c r a r Path: F:\tsg_root\GIS_Workspace\Mike\Radio_Frequency\Radio Frequency_2015.mxd C r e e k KLATTASINE BARB HO WARD A A T H K O l MTN H O M l LANDMAR K a i r r C e t l e a n R CAMBRIDG E t e R Wh i E C V A r I W R K A 7 HIDD EN W E J I C E F I E L D Homathko r C A IE R HEAK E T STANTON PLATEAU A G w r H B T TEAQ UAHAN U O S H N A UA Q A E 8 T H B R O I M Southgate S H T N O K A P CUMSACK O H GALLEO N GUNS IGHT R A E AQ V R E I T R r R I C V E R R MT E H V a RALEIG H SAWT rb S tan I t R o l R A u e E HO USE r o B R i y l I l V B E S E i 4 s i R h t h o 17 S p r O G a c l e Bear U FA LCO N T H G A Stafford R T E R E V D I I R c R SMIT H O e PEAK F Bear a KETA B l l F A T SIR FRANCIS DRAKE C S r MT 2 ke E LILLO OE T La P L rd P fo A af St Mellersh Creek PEAKS TO LO r R GRANITE C E T ST J OHN V MTN I I V E R R 12 R TAHUMMING R E F P i A l R Bute East PORTAL E e A L D S R r A E D PEAK O O A S I F R O T T Glendale 11 R T PRATT S N O N 3 S E O M P Phillip I I T Apple River T O L A B L R T H A I I SIRE NIA E U H V 11 ke Po M L i P E La so M K n C ne C R I N re N L w r ro ek G t B I OSMINGTO N I e e Call Inlet m 28 R l o r T e n T E I I k C Orford V R E l 18 V E a l 31 Toba I R C L R Fullmore 5 HEYDON R h R o George 30 Orford River I Burnt Mtn 16 I M V 12 V MATILPI Browne E GEORGE RIVER E R Bute West R H Brem 13 ke Bute East La G 26 don ey m H r l l e U R -

Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept Prepared by SNC-Lavalin Inc

West Coast Environmental Law Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept Prepared by SNC-Lavalin Inc. 31 July 2018 Document No.: 644868-1000-41EB-0001 Revision: 1 West Coast Environmental Law Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept West Coast Environmental Law Research Foundation and West Coast Environmental Law Association gratefully acknowledge the support of the funders who have made this work possible: © SNC-Lavalin Inc. 2018. All rights reserved. i West Coast Environmental Law Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background West Coast Environmental Law (WCEL) is leading an initiative to explore the implementation of a coastal flood protection system that also protects and enhances existing and future coastal and aquatic ecosystems. The purpose of this document is to summarize available experience and provide an initial technical basis to define how this objective might be realized. This “Living Dike” concept is intended as a best practice measure to meet this balanced objective in response to rising sea levels in a changing climate. It is well known that coastal wetlands and marshes provide considerable protection against storm surge and related wave effects when hurricanes or severe storms come ashore. Studies have also shown that salt marshes in front of coastal sea dikes can reduce the nearshore wave heights by as much as 40 percent. This reduction of the sea state in front of a dike reduces the required crest elevation and volumes of material in the dike, potentially lowering the total cost of a suitable dike by approximately 30 percent. In most cases, existing investigations and studies consider the relative merits of wetlands and marshes for a more or less static sea level, which may include an allowance for future sea level rise. -

3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36

DFO - L bra y MPOBibio heque II 1 111111 11 11 11 V I 1 120235441 3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36 Some If:eat/viz& 3,5,unamia, Olt the Yacific ettadt of South and ✓ cuith anwitica, T. S. Murty, S. 0. Wigen and R. Chawla Marine Sciences Directorate 975 Department of the Environment, Ottawa Marine Sciences Directorate Manuscript. Report Series No. 36 SOME FEATURES OF TSUNAMIS ON THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AND NORTH AM ERICA . 5 . Molly S . O. Wigen and R. Chawla 1975 Published by Publie par Environment Environnement Canada Canada I' Fisheries and Service des !Aches Marine Service et des sciences de la mer Office of the Editor Bureau du fiedacteur 116 Lisgar, Ottawa K1 A Of13 1 Preface This paper is to be published in Spanish in the Proceedings of the Tsunami Committee XVII Meeting, Lima, Peru 20-31 Aug. 1973, under the International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth Interior. 2 Table of Contents Page Abstract - Resume 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Resonance characteristics of sonic inlets on the Pacific Coast of Soulh and North America 13 3. Secondary undulations 25 4. Tsunami forerunner 33 5. Initial withdrawal of water 33 6. Conclusions 35 7. References 37 3 4 i Abstract In order to investigate the response of inlets to tsunamis, the resonance characteristics of some inlets on the coast of Chile have been deduced through simple analytical considerations. A comparison is made with the inlets of southeast Alaska, the mainland coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. It is shown that the general level of intensif yy of secondary undulations is highest for Vancouver Island inlets, and least for those of Chile and Alaska. -

Salish Sea Ambient Noise Study: Best Practices (2021)

Salish Sea Ambient Noise Study: Best Practices (2021) This work was sponsored and financially supported by the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority. Transport Canada provided additional financial support. For bibliographic purposes, this document should be cited as follows: Eickmeier, J., Tollit, D., Trounce, K., Warner, G., Wood, J., MacGillivray, A. and Zizheng Li (2021) Salish Sea Ambient Noise Study: Best Practices (2021). Vancouver, British Columbia, Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program. Authors: Justin Eickmeier1, Dominic Tollit2, Krista Trounce3, Graham Warner4, Jason Wood5, Alex MacGillivray6 and Zizheng Li7 1) Justin M. Eickmeier is a Consulting Scientist at SLR Consulting (Canada) Ltd., Vancouver, British Columbia, V6J 1V4 ([email protected]) 2) Dominic J. Tollit is the Principal Scientist at SMRU Consulting North America, Vancouver, British Colunbia, V6B 1A1 ([email protected]) 3) Krista B. Trounce is the Research Manager for the ECHO Program, Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C 3T4 ([email protected]) 4) Graham Warner is a Project Scientist for JASCO Applied Sciences (Canada) Ltd. 5) Jason Wood is Operations Manager & Senior Research Scientist at SMRU Consulting North America 6) Alex MacGillivray is a Senior Scientist for JASCO JASCO Applied Sciences (Canada) Ltd. 7) Zizheng Li is a Project Scientist for JASCO JASCO Applied Sciences (Canada) Ltd. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

ECHO Program Salish Sea Ambient Noise Evaluation

Vancouver Fraser Port Authority Salish Sea Ambient Noise Evaluation 2016–2017 ECHO Program Study Summary This study was undertaken for Vancouver Fraser Port Authority’s Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program to analyze regional acoustic data collected over two years (2016–2017) at three sites in the Salish Sea: Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and the Strait of Georgia. These sites were selected by the ECHO Program to be representative of three sub-areas of interest in the region in important habitat for marine mammals, including southern resident killer whales (SRKW). This summary document describes how and why the project was conducted, its key findings and conclusions. What questions was the study trying to answer? The ambient noise evaluation study investigated the following questions: What were the variabilities and/or trends in ambient noise over time and for each site, and did these hold true for all three sites? What key factors affected ambient noise differences and variability at each site? What are the key requirements for future monitoring of ambient noise to better understand the contribution of commercial vessel traffic to ambient noise levels, and how ambient noise may be monitored in the future? Who conducted the project? JASCO Applied Sciences (Canada) Ltd., SMRU Consulting North America, and the Coastal & Ocean Resource Analysis Laboratory (CORAL) of University of Victoria were collaboratively retained by the port authority to conduct the study. All three organizations were involved in data collection and analysis at one or more of the three study sites over the two-year time frame of acoustic data collection. -

Hail the Columbia III

Hail the Columbia III Toronto , Ontario , Canada Friday, June 20, 2008 TO VANCOUVER AND BEYOND: About a year earlier, my brother Peter and his wife Lynn, reported on a one-of-a-kind cruise adventure they had in the Queen Charlotte Strait area on the inside passage waters of British Columbia. Hearing the stories and seeing the pictures with which they came back moved us to hope that a repeat voyage could be organized. And so we found ourselves this day on a WestJet 737 heading for Vancouver. A brief preamble will help set the scene: In 1966 Peter and Lynn departed the civilization of St. Clair Avenue in Toronto, for the native community of Alert Bay, on Cormorant Island in the Queen Charlotte Strait about 190 miles, as the crow flies, north-west of Vancouver. Peter was a freshly minted minister in the United Church of Canada and an airplane pilot of some experience. The United Church had both a church and a float-equipped airplane in Alert Bay. A perfect match. The purpose of the airplane was to allow the minister to fly to the something over 150 logging camps and fishing villages that are within a couple hundred miles of Alert Bay and there to do whatever it is that ministers do. This was called Mission Service. At the same time the Anglican Church, seeing no need to get any closer to God than they already were, decided to stay on the surface of the earth and so Horseshoe Bay chugged the same waters in a perky little ship. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 W Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug

Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 w Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug. 1995 July 2005 Port Townsend 25,000 47 w Puget Sound – Point No Point to Alki Point 50,000 Mar. 1996 Sept. 2003 Everett 12,500 48 w Puget Sound – Alki Point to Point Defi ance 50,000 Dec. 1995 Aug. 2011 A Tacoma 15,000 B Continuation of A 15,000 50 w Puget Sound – Seattle Harbor 10,000 Mar. 1995 June 2001 Q1 Continuation of Duwamish Waterway 10,000 51 w Puget Sound – Point Defi ance to Olympia 80,000 Mar. 1998 - A Budd Inlet 20,000 B Olympia (continuation of A) 20,000 80 w Rosario Strait 50,000 Mar. 1995 June 2011 1717w Ports in Juan de Fuca Strait - July 1993 July 2007 Neah Bay 10,000 Port Angeles 10,000 1947w Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound 139,000 Oct. 1893 Sept. 2003 2531w Cape Mendocino to Vancouver Island 1,020,000 Apr. 1884 June 1978 2940w Cape Disappointment to Cape Flattery 200,000 Apr. 1948 Feb. 2003 3125w Grays Harbor 40,000 July 1949 Aug. 1998 A Continuation of Chehalis River 40,000 4920w Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 Mar. 2005 - 4921w Queen Charlotte Sound to / à Dixon Entrance 525,000 Oct. 2008 - 4922w Vancouver Island / Île de Vancouver-Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Queen 525,000 Mar. 2005 - Charlotte Sound 4923w Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 Mar. -

Proposed Southern Strait of Georgia NMCA Atlas

OCEANOGRAPHIC INFORMATION 2 DIVERSITY body of water sheltered from Snapshots of oceanographic the wind, with little current processes in the southern and relatively low levels of Strait of Georgia reveal a fresh water input, level of diversity that is is an area of exceptionally uncommon for such a small high stratification. If the geographic area. Due in part waters could be removed to the freshwater discharge and looked at in profile, from the Fraser River, the there would be clearly upwelling from Haro Strait, defined layers each with and the varied seabed below, different characteristics. there is a wide range of In contrast, because of the temperatures, salinity levels, large volume of water that currents and stratification. must squeeze through a tiny, twisting channel, Active Pass EXTREMES has waters that are so highly The southern Strait of mixed and churned that the Georgia is more than diverse; phenomenon is visible from it is a zone of extremes. For ferry decks above! instance, Saanich Inlet, a deep INTERESTING The water in the Strait of Georgia is not much colder than the waters of northern California. INFO Surface waters move much faster than deeper waters. To travel from the southern Strait of Georgia to the Juan de Fuca Strait, a log at the surface takes only 24 hours; a waterlogged piece of wood 50 metres below takes a full year! The Fraser River accounts for roughly 80% of the freshwater entering the Strait of Georgia. 11 • PROPOSED SOUTHERN STRAIT OF GEORGIA NATIONAL MARINE CONSERVATION AREA RESERVE ATLAS – CHAPTER 2 • Supplemental Information Article References • Dr.