Joint Review Panel Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREATY 8: a British Columbian Anomaly

TREATY 8: A British Columbian Anomaly ARTHUR J. RAY N THE ANNALS OF NATIVE BRITISH COLUMBIA, 1999 undoubtedly will be remembered as the year when, in a swirl of controversy, Ithe provincial legislature passed the Nisga'a Agreement. The media promptly heralded the agreement as the province's first modern Indian treaty. Unmentioned, because it has been largely forgotten, was the fact that the last major "pre-modern" agreement affecting British Columbia -Treaty 8 - had been signed 100 years earlier. This treaty encompasses a sprawling 160,900-square-kilometre area of northeastern British Columbia (Map 1), which is a territory that is nearly twenty times larger than that covered by the Nisga'a Agreement. In addition, Treaty 8 includes the adjoining portions of Alberta and the Northwest Territories. Treaty 8 was negotiated at a time when British Columbia vehemently denied the existence of Aboriginal title or self-governing rights. It therefore raises two central questions. First, why, in 1899, was it ne cessary to bring northeastern British Columbia under treaty? Second, given the contemporary Indian policies of the provincial government, how was it possible to do so? The latter question raises two other related issues, both of which resurfaced during negotiations for the modern Nisga'a Agreement. The first concerned how the two levels of government would share the costs of making a treaty. (I will show that attempts to avoid straining federal-provincial relations over this issue in 1899 created troublesome ambiguities in Treaty 8.) The second concerned how much BC territory had to be included within the treaty area. -

Williston-Dinosaur Watershed Fish Mercury Investigation 2017 Report

Williston-Dinosaur Watershed Fish Mercury Investigation 2017 Report Prepared for: Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, Peace Region 3333 22nd Ave. Prince George, BC V2N 1B4 June 2018 Azimuth Consulting Group Partnership 218-2902 West Broadway Vancouver BC, V6K 2G8 Project No. CO94394 Williston-Dinosaur Watershed Fish Mercury Investigation – 2017 Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program (FWCP) – Peace Region carried out a strategic planning process in 2012-13 to review and identify program priorities in this region. Guided by a Strategic Planning Group (SPG), including First Nations, academia, BC Hydro and the FWCP-Peace Board, a Peace Basin Plan and six Action Plans were finalized in 2014. Objective 3a of the Reservoirs Action Plan is to “Improve understanding of mercury concentrations, contamination pathways and potential effects on human health and the broader ecosystem.” Initial efforts on this objective were commissioned by FWCP Peace in 2014 and identified the need to obtain updated information on fish mercury concentrations and consumption habits. In 2016, the Azimuth Consulting Group (Azimuth) team (including EDI Environmental Dynamics [EDI], Chu Cho Environmental [CCE] and Hagen and Associates) was awarded a multi-year contract to collect fish mercury data from the Parsnip, Peace, Finlay reaches of Williston and Dinosaur reservoirs and reference lakes (i.e., the Williston-Dinosaur Watershed Fish Mercury Study). Results of this investigation will assess provide an updated fish mercury database for the Williston-Dinosaur watershed and understanding of how results compare with nearby reference lakes. The long-term goal is to ‘update’ the existing fish consumption advisory, in partnership with provincial health agencies. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

Bcts Dcr, Dsc

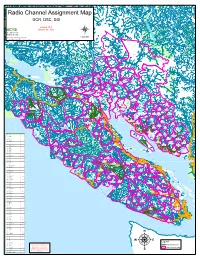

Radio Channel Assignment Map DCR, DSC, DSI Version 10.8 BCTS January 30, 2015 BC Timber Sales W a d d i Strait of Georgia n g t o n G l a 1:400,000 c Date Saved: 2/3/2015 9:55:56 AM i S e c r a r Path: F:\tsg_root\GIS_Workspace\Mike\Radio_Frequency\Radio Frequency_2015.mxd C r e e k KLATTASINE BARB HO WARD A A T H K O l MTN H O M l LANDMAR K a i r r C e t l e a n R CAMBRIDG E t e R Wh i E C V A r I W R K A 7 HIDD EN W E J I C E F I E L D Homathko r C A IE R HEAK E T STANTON PLATEAU A G w r H B T TEAQ UAHAN U O S H N A UA Q A E 8 T H B R O I M Southgate S H T N O K A P CUMSACK O H GALLEO N GUNS IGHT R A E AQ V R E I T R r R I C V E R R MT E H V a RALEIG H SAWT rb S tan I t R o l R A u e E HO USE r o B R i y l I l V B E S E i 4 s i R h t h o 17 S p r O G a c l e Bear U FA LCO N T H G A Stafford R T E R E V D I I R c R SMIT H O e PEAK F Bear a KETA B l l F A T SIR FRANCIS DRAKE C S r MT 2 ke E LILLO OE T La P L rd P fo A af St Mellersh Creek PEAKS TO LO r R GRANITE C E T ST J OHN V MTN I I V E R R 12 R TAHUMMING R E F P i A l R Bute East PORTAL E e A L D S R r A E D PEAK O O A S I F R O T T Glendale 11 R T PRATT S N O N 3 S E O M P Phillip I I T Apple River T O L A B L R T H A I I SIRE NIA E U H V 11 ke Po M L i P E La so M K n C ne C R I N re N L w r ro ek G t B I OSMINGTO N I e e Call Inlet m 28 R l o r T e n T E I I k C Orford V R E l 18 V E a l 31 Toba I R C L R Fullmore 5 HEYDON R h R o George 30 Orford River I Burnt Mtn 16 I M V 12 V MATILPI Browne E GEORGE RIVER E R Bute West R H Brem 13 ke Bute East La G 26 don ey m H r l l e U R -

3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36

DFO - L bra y MPOBibio heque II 1 111111 11 11 11 V I 1 120235441 3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36 Some If:eat/viz& 3,5,unamia, Olt the Yacific ettadt of South and ✓ cuith anwitica, T. S. Murty, S. 0. Wigen and R. Chawla Marine Sciences Directorate 975 Department of the Environment, Ottawa Marine Sciences Directorate Manuscript. Report Series No. 36 SOME FEATURES OF TSUNAMIS ON THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AND NORTH AM ERICA . 5 . Molly S . O. Wigen and R. Chawla 1975 Published by Publie par Environment Environnement Canada Canada I' Fisheries and Service des !Aches Marine Service et des sciences de la mer Office of the Editor Bureau du fiedacteur 116 Lisgar, Ottawa K1 A Of13 1 Preface This paper is to be published in Spanish in the Proceedings of the Tsunami Committee XVII Meeting, Lima, Peru 20-31 Aug. 1973, under the International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth Interior. 2 Table of Contents Page Abstract - Resume 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Resonance characteristics of sonic inlets on the Pacific Coast of Soulh and North America 13 3. Secondary undulations 25 4. Tsunami forerunner 33 5. Initial withdrawal of water 33 6. Conclusions 35 7. References 37 3 4 i Abstract In order to investigate the response of inlets to tsunamis, the resonance characteristics of some inlets on the coast of Chile have been deduced through simple analytical considerations. A comparison is made with the inlets of southeast Alaska, the mainland coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. It is shown that the general level of intensif yy of secondary undulations is highest for Vancouver Island inlets, and least for those of Chile and Alaska. -

Proquest Dissertations

The Distribution of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tar and us caribou) and Moose (Alces alces) in the Fort St. James Region of Northern British Columbia, 1800-1950 Domenico Santomauro B.A., University of Bologna, Italy, 2003 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Master in Natural Resources and Environmental Studies The University of Northern British Columbia September 2009 © Domenico Santomauro, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f£rence ISBN: 978-0-494-60853-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-60853-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

Rainbows on the Firesteel

on RAINBOWSthe FIRESTEEL Pretty nice rainbow trout – 22 inches – LARRY’S SHORT STORIES #77 – n the wild and remote areas of western Canada, they use Son Russell and I fi shed this magnifi cent river for a couple Ithe term ‘fl y-out’ fi shing; as the only way to get you to of days – fi rst, at the outlet of the lake, where 100 fi sh per most of the best streams and lakes is to ‘fl y-out’ from base person was the expected day. Then we fi shed the main camp – in a small plane, with fl oats attached to the landing part of the river, below and between some falls, where we gear. At the end of the day’s fi shing, you fl y back and caught fewer, but bigger fi sh. Russell is a more serious make plans to fi sh a different river ‘tomorrow’ -- in another fl y fi sherman than myself. I took one fl y rod, he took fi ve. remote location. The daily plane rides between base camp Mostly we used and the fi sheries become something to look forward to, as dry fl ies and "...6,000 rainbow they provide a spectacular view of the scenery and wildlife. the fi sh would When fi shing the rivers, there are often three choices – readily take trout per mile..." each generally being a single destination for the day; you them, even if can fi sh the outlet of the lake, where the river begins, the there were no apparent rises. Everything was catch and inlet, or along the course of the river -- if the pools are release, with barbs down, but we did enjoy fresh rainbow large and deep enough to accommodate the landing trout during two different shore lunches. -

Copyright (C) Queen's Printer, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

B.C. Reg. 38/2016 O.C. 112/2016 Deposited February 29, 2016 effective February 29, 2016 Water Sustainability Act WATER DISTRICTS REGULATION Note: Check the Cumulative Regulation Bulletin 2015 and 2016 for any non-consolidated amendments to this regulation that may be in effect. Water districts 1 British Columbia is divided into the water districts named and described in the Schedule. Schedule Water Districts Alberni Water District That part of Vancouver Island together with adjacent islands lying southwest of a line commencing at the northwest corner of Fractional Township 42, Rupert Land District, being a point on the natural boundary of Fisherman Bay; thence in a general southeasterly direction along the southwesterly boundaries of the watersheds of Dakota Creek, Laura Creek, Stranby River, Nahwitti River, Quatse River, Keogh River, Cluxewe River and Nimpkish River to the southeasterly boundary of the watershed of Nimpkish River; thence in a general northeasterly direction along the southeasterly boundary of the watershed of Nimpkish River to the southerly boundary of the watershed of Salmon River; thence in a general easterly direction along the southerly boundary of the watershed of Salmon River to the southwesterly boundary thereof; thence in a general southeasterly direction along the southwesterly boundaries of the watersheds of Salmon River and Campbell River to the southerly boundary of the watershed of Campbell River; thence in a general easterly direction along the southerly boundaries of the watersheds of Campbell River and -

British Columbia Geological Survey Geological Fieldwork 1989

GEOLOGY BETWEEN NINA LAKE AND OSILINKA RIVE,R, NORTH-CENTRAL BRITISH COLUMBIA (93N/15, NORTH HALF AND 94C/2, SOUTH HALF) By Filippo Ferri and David M. Melville KEYWORDS: Regionalmapping, Germansen Landing, The northern and eastem sections of the map are bounded, Omineca Belt. Intermontane Superterrane, Slide Mountain respectively, by the Osilinka and 0mine:ca rivers. At lheir Group, Paleozoicstratigraphy, lngenika Group, metamor- confluence the terrainis a relatively subdued and tree covzred phism, lead-zinc-silr,er-baritemineralization area. This is in contrast to the Wolverine Range east oithe OminecaRiverand arugged, unnamedrangeof mountai'ls to the southwest. The southern part of the map area was first mapped at a INTRODUCTION 6-mile scale in the 1940s by Amstrong; (1949).Gahrlelse (1975) examined the northem half in the course of 1:250 000 In 1989 theManson Creek 150 000 mappingproject mapping of the east half of the Fort Grahame map area. encompassed the north half of the Germansen Landing map Monger (1973), and Monger and Patersan (1974) described area (93Ni15) and the south half of the End Lake map area rocks in the map area during a reconnaissance sunfey of (94Ci2). As with previous years, the main aims of this project Paleozoic stratigraphy. To the northwest, Roots (1954) pub- were: to provide a detailed geologicalbase map of the area, to lished a 4-mile map of the Fort Graham west-half sheet. update the mineral inventory database, and to place known Many ofthe correlations made in this paper arewith stratigra- mineral occurrences within a geological framework. phy described by Gabrielse (1963, 1969:1,Nelson and Eirad- ford (1987) and other workers in the Casiar area whera: the The centreof the map area is located some 260kilometres miogeoclinal stratigraphy is quite similar and well known. -

Williston Reservoir Bathymetry

Peace River Project Water Use Plan Williston Reservoir Bathymetry Reference: GMSWORKS 25 Williston Reservoir Bathymetric Mapping Study Period: June 2010 to June 2013 Final Terrasond Precision Geospatial Solutions December 31, 2013 WILLISTON RESERVOIR BATHYMETRIC MAPPING GMSWORKS #25 Contract No. CO50616 Project Report Report Date: December 31, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PROJECT LOCATION .................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 SCOPE OF WORK ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Terms of Reference ....................................................................................................................... 2 3.0 SURVEY TEAM .......................................................................................................................... 2 4.0 SURVEY DATES .......................................................................................................................... 3 5.0 HORIZONTAL CONTROL ............................................................................................................ 4 5.1 Horizontal Datums ........................................................................................................................ 4 5.2 Horizontal Accuracy ...................................................................................................................... 4 5.3 Horizontal Control and Verification ............................................................................................. -

Original Field Data and Traverse Notes Must Be Provided by the Licensee

Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development Minister’s Office MEMORANDUM Cliff: 259440 Ref: 280-20 November 25, 2020 To: Sharon Hadway, Regional Executive Director, West Coast Allan Johnsrude, Regional Executive Director, South Coast From: The Honourable Doug Donaldson Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development Re: New Coast Appraisal Manual I hereby approve the new Coast Appraisal Manual and attach a copy for your use. The manual is available at the following link: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/competitive-forest-industry/ timber-pricing/coast-timber-pricing/coast-appraisal-manual-and-amendments This manual will come into force on December 15, 2020. Further amendments or revisions to this manual require my approval. Minister pc: Melissa Sanderson, Assistant Deputy Minister, Forest Policy and Indigenous Relations Division Jim Schafthuizen, Executive Director, Forest Policy and Indigenous Relations Division Allan Bennett, Director, Timber Pricing Branch TIMBER PRICING BRANCH Coast Appraisal Manual Effective December 15, 2020 This manual is intended for the use of individuals or companies when conducting business with the British Columbia Government. Permission is granted to reproduce it for such purposes. This manual and related documentation and publications, are protected under the Federal Copyright Act. They may not be reproduced for sale or for other purposes without the express written permission of the Province of British Columbia. Coast Appraisal Manual Highlights New Coast Appraisal Manual Highlights The new Coast Appraisal Manual includes clarification to policy, an update to the market pricing system, and an update of the tenure obligation adjustments and specified operations for December 15, 2020 onward.