Klahoose First Nation Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia Immerse yourself in the living Traditions Indigenous travel experiences have the power to move you. To help you feel connected to something bigger than yourself. To leave you changed forever, through cultural exploration and learning. Let your true nature run free and be forever transformed by the stories and songs from the world’s most diverse assembly of living Indigenous cultures. #IndigenousBC | IndigenousBC.com Places To Go CARIBOO CHILCOTIN COAST KOOTENAY ROCKIES NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TŜILHQOT’IN | TSE’KHENE | DANE-ZAA | ST̓ÁT̓IMCETS KTUNAXA | SECWEPEMCSTIN | NSYILXCƏN SM̓ALGYA̱X | NISG̱A’A | GITSENIMX̱ | DALKEH | WITSUWIT’EN SECWEPEMCSTIN | NŁEʔKEPMXCÍN | NSYILXCƏN | NUXALK NEDUT’EN | DANEZĀGÉ’ | TĀŁTĀN | DENE K’E | X̱AAYDA KIL The Ktunaxa have inhabited the rugged area around X̱AAD KIL The fjordic coast town of Bella Coola, where the Pacific the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers on the west side of Ocean meets mighty rainforests and unmatched Canada’s Rockies for more than 10 000 years. Visitors Many distinct Indigenous people, including the Nisga’a, wildlife viewing opportunities, is home to the Nuxalk to the snowy mountains of Creston and Cranbrook Haida and the Tahltan, occupy the unique landscapes of people and the region’s easternmost point. The continue to seek the adventure this dramatic landscape Northern BC. Indigenous people co-manage and protect Cariboo Chilcotin Coast spans the lower middle of offers. Experience traditional rejuvenation: soak in hot this untamed expanse–more than half of the size of the BC and continues toward mountainous Tsilhqot’in mineral waters, view Bighorn Sheep, and traverse five province–with a world-class system of parks and reserves Territory, where wild horses run. -

Quadra Island Builds Seniors Housing

ISSUE 478 www.discoveryislander.ca JULY 16, 2010 Stakeholders gather at the Quadra Seniors Housing Project site with the two Program Officers Mary Crowley and Karen Johnson from the Ministry of Housing and Social Development (fifth and sixth from the left). Quadra Island Builds Seniors Housing The Quadra Island Seniors Housing Society has begun construction Development Permit allows a total of three duplexes (6 units) to be of affordable, duplex rental units, specifically designed for seniors, in built. The Coastal Community Credit Union has donated a substantial Quathiaski Cove. Until now, many seniors have been forced to move off grant through the Quadra Branch’s Legacy Fund. Many of the Quadra when they could no longer maintain their home and property. tradespeople working on this project will be donating a portion of their These independent living homes will allow seniors to continue to live in time. A unique fundraising strategy was used when the $1000 Club was and contribute to their community. established - thirty six community members to date have joined this Thanks to a Job Creation Partnership with the Ministry of Housing special Seniors Housing Support Club. and Social Development sponsored by the Canada - British Columbia The Society would like to thank the Ministry of Housing and Social Labour Market Development Agreement, the Society expects to Development, the Strathcona Regional District, Coastal Community complete one duplex for low to moderate income seniors by this year Credit Union, the Royal Canadian Legion Branch 154, Quadra Island end. After many years of dedicated fundraising and volunteerism, Seniors Br.91 of BC O.A.P.O., the Real Estate Foundation of BC, Telus, the Quadra Island community is very happy to have received this Job and the community’s generous donors of cash and services. -

Commercial Fishing Guide

1981 Commercial Fishing Guide Includes: STOCK EXPECTATIONS and PROPOSED FISHING PLANS Government Gouvernement I+ of Canada du Canada Fisheries Pech es and Oceans et Oceans LIBRARY PACIFIC BIULUG!CAL STATION ADDENDUM 1981 Commercial Fishing Guide - Page 28 Two-Area Troll Licensing - clarification Fishermen electing for an inside licence will receive an inside trolling privilege only and will not be eligible to participate in any other salmon fishery on the coast. Fishermen electing for an outside licence may participate in any troll or net fishery on the coast except the troll fishery in the Strait of Georgia. , ....... c l l r t 1981 Commercial Fishing Guide Department of Fisheries and Oceans Pacific Region 1090 West Pender Street Vancouver, B.C. Government Gouvernement I+ of Canada du Canada Fisheries Pee hes and Oceans et Oceans \ ' Editor: Brenda Austin Management Plans Coordinator: Hank Scarth Cover: Bev Bowler Canada Joe Kambeitz 1981 Calendar JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH s M T w T F s s M T w T F s s M T w T F s 2 3 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1-1 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15 -16 17 18 19 20 21 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 ?2 23 _24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 APRIL MAY JUNE s M T w T F s s M T w T F s s M T w T F s 1 2 3 4 1 2 2 3 4 5 6 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 -

Heriot Bay Rd

Quadra Island Streets THE COMPLETE GUIDE (with maps) TO THE RESIDENTIAL STREETS & ROADS of QUADRA ISLAND,BC, in 2020 Including: Roads, Lanes, Ways, Places, Drives, Crescents etc., REVISED AND UPDATED EDITION, December 17th 2020 ISBN 978-1-927442-29-6 Canadian Catalogue of Publishing, Ottawa. Compiled by Quadra Island Community Members. Published on Quadra Island, BC, Canada, December, 2020. Quadra Island, pop. 3,000 British Columbia, BC, Canada Page 1 Index of Quadra Island Street Names, with their map reference in this street-map book. Index S treet Name Hint MAP No. Alder Place 5 runs off Cedar Drive Anderson Road 3 & 4 borders school’s west Animal Farm Road 5 runs off Heriot Bay Rd. Antler Road 6 runs off Cramer Rd. April Point Road 4 begins at Ferry Rd. Banning Road 8 Granite Bay Barton Road 5 runs off Milton Road Bold Point Road 8 & 9 runs past V.B. Lakes Breton Road 8 runs off Valdes Drive Buker Road 6 central Hooleyville Bull Road 6 runs off West Rd. Cape Mudge Road 1, 2 & 3 south end Quadra Cedar Drive 5 runs off Smith Road Cherrier Rd 9 runs off Conville Bay Rd. Chinook Cresent 2 runs off Upper Ridge Rd. Cliff Road 5 off end of Vaughn Road Conville Bay Road 9 runs off Bold Point Rd. Conville Point Road 9 near Main Lake Colter Road 3 runs off Helanton Road Cove Crescent 3 runs off Green Rd . Cramer Road 6 runs off West Rd . Page 2 STREET NAME MAP NO. HINT Cutter Road 6 runs off Hooley Rd. -

ARC174 Timberwest TFL47

Audit of Forest Planning and Practices TimberWest Forest Corporation Tree Farm Licence 47 FPB/ARC/174 February 2015 Table of Contents Audit Results ................................................................................................................................1 Background ................................................................................................................................1 Audit Approach and Scope .........................................................................................................2 Planning and Practices Examined ..............................................................................................2 Findings ......................................................................................................................................3 Audit Opinion ..............................................................................................................................5 Appendix 1: Forest Practices Board Compliance Audit Process ............................................6 Audit Results Background As part of the Forest Practices Board's 2014 compliance audit program, the Board randomly selected the Campbell River District as the location for a full scope compliance audit. Within the district, the Board selected Tree Farm Licence (TFL) 47, held by TimberWest Forest Corporation (TimberWest), for the audit. TFL 47 is located north of Campbell River, along Johnstone Strait, and southeast of Port McNeill. TimberWest’s activities were located in 12 forest development -

For Immediate Release 10-007 March 3, 2010 BC

For Immediate Release 10-007 March 3, 2010 BC FERRIES ANNOUNCES QUADRA AND CORTES ISLANDS SERVICE DURING TEMPORARY DOCK CLOSURE Quathiaski Cove terminal closed April 6 through 10 for construction VICTORIA – BC Ferries’ dock at Quathiaski Cove on Quadra Island will be temporarily closed for five days while a new berthing structure is installed. Alternate service will be provided for both Quadra and Cortes Islands during the dock closure from April 6 through 10, 2010. BC Ferries is making this significant investment at Quathiaski Cove to ensure continued safe, reliable service for years to come. The $5.3 million project includes the replacement of the ramp, pontoon, wingwalls and waiting shelter. While work on the project began at the beginning of February and will conclude at the end of April, BC Ferries has pre-fabricated the berthing structure and other components off-site to minimize the necessary dock closure period. During the closure the MV Tachek will operate between Campbell River and Heriot Bay terminal on Quadra Island, transporting commercial and essential vehicle traffic only. Beginning March 15, all customers will be required to reserve their desired sailing by calling 1-888-BC FERRY (1-888-223-3779). The MV Tenaka will operate between Campbell River and Whaletown terminal on Cortes Island. All vehicular and foot traffic are welcome and will be loaded on a first-come- first-serve basis. Both vessels will operate three round-trip voyages each day. In addition, a water taxi service will be available to transport foot passengers between Campbell River and Quathiaski Cove terminals. -

28–August 10, 2011 $2 at Selected Retailers Sales Agreement Nº 40020421

Gulf Islands Every Second Thursday & Online ‘24/7’ at Uniting The Salish Sea ~ From Coast to Coast to Coast islandtides.com Canadian Publications Mail Product Volume 23 Number 15 July 28–August 10, 2011 $2 at Selected Retailers Sales Agreement Nº 40020421 Photo: Derek Holzapfel One of the first hot, dry days of summer meant haying time at Whalewich Farm on South Pender Island. With volunteer help from the community, 517 bales were processed in two hours. Quite a feat! The rising tide of island radio ~ Sara Miles Crafting a carbon tax ~ Richard Curchin embers of Gabriola Co-op Radio to develop partnerships with community On July 10, the Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced that CKGI-FM are waiting to hear if their groups that can benefit from their planned agreement had been reached between the Australian Labor Party, the Australian baby will finally find a home on the earthquake-proof transmission tower. The M Green Party and independent Australian Federal MPs to legislate the airwaves. CKGI’s application for the frequency RCMP and first responders could use the 80- introduction of a carbon tax in Australia from July 1, 2012. 98.7FM was reviewed by the CRTC on July 18. watt radio tower to enhance their signals. It Back in 2010, the Labor government tried to pass an act to introduce a carbon If it passes, they will then have 18 months to would have its own backup power so that when pollution reduction scheme based on an emissions trading scheme. This act was get on-air and fulfill their mandate before they all other communications are down, the radio defeated as it was opposed by both the conservative opposition and the Greens. -

Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Region of British Columbia

MARINE RECREATION IN THE DESOLATION SOUND REGION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA by William Harold Wolferstan B.Sc., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography @ WILLIAM HAROLD WOLFERSTAN 1971 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December, 1971 Name : William Harold Wolf erstan Degree : Master of Arts Title of Thesis : Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Area of British Columbia Examining Committee : Chairman : Mar tin C . Kellman Frank F . Cunningham1 Senior Supervisor Robert Ahrens Director, Parks Planning Branch Department of Recreation and Conservation, British .Columbia ABSTRACT The increase of recreation boating along the British Columbia coast is straining the relationship between the boater and his environment. This thesis describes the nature of this increase, incorporating those qualities of the marine environment which either contribute to or detract from the recreational boating experience. A questionnaire was used to determine the interests and activities of boaters in the Desolation Sound region. From the responses, two major dichotomies became apparent: the relationship between the most frequented areas to those considered the most attractive and the desire for natural wilderness environments as opposed to artificial, service- facility ones. This thesis will also show that the most valued areas are those F- which are the least disturbed. Consequently, future planning must protect the natural environment. Any development, that fails to consider the long term interests of the boater and other resource users, should be curtailed in those areas of greatest recreation value. iii EASY WILDERNESS . Many of us wish we could do it, this 'retreat to nature'. -

Hail the Columbia III

Hail the Columbia III Toronto , Ontario , Canada Friday, June 20, 2008 TO VANCOUVER AND BEYOND: About a year earlier, my brother Peter and his wife Lynn, reported on a one-of-a-kind cruise adventure they had in the Queen Charlotte Strait area on the inside passage waters of British Columbia. Hearing the stories and seeing the pictures with which they came back moved us to hope that a repeat voyage could be organized. And so we found ourselves this day on a WestJet 737 heading for Vancouver. A brief preamble will help set the scene: In 1966 Peter and Lynn departed the civilization of St. Clair Avenue in Toronto, for the native community of Alert Bay, on Cormorant Island in the Queen Charlotte Strait about 190 miles, as the crow flies, north-west of Vancouver. Peter was a freshly minted minister in the United Church of Canada and an airplane pilot of some experience. The United Church had both a church and a float-equipped airplane in Alert Bay. A perfect match. The purpose of the airplane was to allow the minister to fly to the something over 150 logging camps and fishing villages that are within a couple hundred miles of Alert Bay and there to do whatever it is that ministers do. This was called Mission Service. At the same time the Anglican Church, seeing no need to get any closer to God than they already were, decided to stay on the surface of the earth and so Horseshoe Bay chugged the same waters in a perky little ship. -

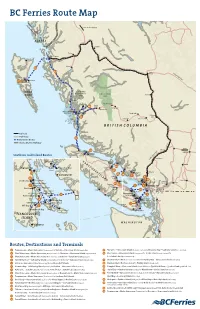

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

STAFF REPORT DATE: July 12, 2019 FILE: 0540-04 EASC TO: Chair and Directors Electoral Areas Services Committee FROM: Dave Leitch

STAFF REPORT DATE: July 12, 2019 FILE: 0540-04 EASC TO: Chair and Directors Electoral Areas Services Committee FROM: Dave Leitch Chief Administrative Officer RE: REZONING APPLICATIONS TO FACILITATE PRIVATE MOORAGE USE OF CROWN FORESHORE AT (A) SHOAL BAY, EAST THURLOW ISLAND, (B) DEEPWATER BAY, QUADRA ISLAND, AND (C) 2011 VALDES DRIVE, HERIOT BAY, QUADRA ISLAND. PLANNING FILE NOS. 3360-20/RZ 5C 19, RZ 6C 19 and RZ 7C 19 CROWN LAND TENURES: N/A PID NOS.: N/A APPLICANTS: Site 1 - John Moss / Laura Herro (Agent: Derek LeBouef) Site 2 - Bear Lake Holdings Ltd. (Devin Sweeney) Site 3 - Sean and Sharmina Murphy (Agent: Chris Bunn) LAND DESCRIPTIONS: Site 1 – Shoal Bay, East Thurlow Island (see Bylaw No. 355) That part of unsurveyed Crown foreshore or land covered by water being part of the bed of Shoal Bay, East Thurlow Island, within a 50-metre wide strip abutting District Lot 113, Range 1, Coast District, containing in total approximately 8.5 hectares. Site 2 – Deepwater Bay, Quadra Island (see Bylaw No. 356) That part of unsurveyed Crown foreshore or land covered by water being part of the bed of Deepwater Bay, within a 50-metre wide strip abutting District Lot 1493, Sayward District, Quadra Island, containing in total approximately 2.9 hectares. Site 3 – 2011 Valdes Drive, Heriot Bay, Quadra Island (see Bylaw No. 361) That part of unsurveyed Crown foreshore or land covered by water being part of the bed of Open Bay, within a 65-metre wide strip abutting the west shore of Lot 1, District Lot 1028, Sayward District, Quadra Island, Plan 42646, containing in total approximately 0.75 hectares. -

Poster (7.573Mb)

T h e C o a s t - Insular Boundary Revisited: Mid-Jurassic ductile deformation on Quadra Island, British Columbia Sandra Johnstone [email protected]; Vancouver Island University, 900 Fifth Street, Nanaimo British Columbia, V9R 5S5 Project Overview Relationship to Strongly deformed basalt dikes are boudined and transposed parallel Sample Description Ductile Strongly Deformed Dike to bedding. Mineralogy of OB-14-26 is dominated by subhedral laths 35 Post-Deformation Intrusions The boundary between the Insular and Coast geomorphological belts of the North American Cordillera is well exposed at Open Deformation of strongly sericitized plagioclase averaging 0.5mm (70%), with 20% Samples OB-14-24 and OB-14-27 are both intrusive phases that cross-cut ductile deformation struc- N Bay, on Quadra Island, British Columbia. On the southwestern side of the boundary at Open Bay is the upper Triassic-aged actinolite that may be an alteration product of hornblende. Unfortu- N Basaltic Pre– or early syn- 83 tures. OB-14-24 is an ~5m wide unfoliated plagioclase-phyric dacite dike. OB-14-24 zircons are zoned Quatsino limestone and Karmutsen basalts of the Wrangellia terrane. On the northeastern side of the boundary are intrusive OB-14-26 nately only one zircon was recovered from Sample OB-14-26. This andesite pod deformation 65 single zircon yielded a concordant age of 157.6 ± 8.9 Ma. euhedral to subhedral crystals and some fragments; nineteen crystals yield an age of 158.7 ± 0.8 Ma. phases of the Coast Batholith. At Open Bay the Quatsino limestone (Upper Triassic) has been subjected to strong ductile defor- N Folded mation resulting in re-folded transposed bedding.