023810 Rangifer Spec Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Complete Dissertation Kua 1

Trends and Ontology of Artistic Practices of the Dorset Culture 800 BC - 1300 AD Hardenberg, Mari Publication date: 2013 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Hardenberg, M. (2013). Trends and Ontology of Artistic Practices of the Dorset Culture 800 BC - 1300 AD. København: Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 08. Apr. 2020 Trends and Ontology of Artistic Practices of the Dorset Culture 800 BC – 1300 AD Volume 1 By © Mari Hardenberg A Dissertation Submitted to the Ph.d.- School In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy SAXO-Institute, Department of Prehistoric Archaeology, Faculty of Humanities University of Copenhagen August 2013 Copenhagen Denmark ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the various artistic carvings produced by the hunter-gatherer Dorset people who occupied the eastern Arctic and temperate regions of Canada and Greenland between circa BC 800 – AD 1300. It includes considerations on how the carved objects affected and played a role in Dorset social life. To consider the role of people, things and other beings that may be said to play as actors in interdependent entanglements of actions, the agency/actor- network theory is employed. From this theoretical review an interpretation of social life as created by the ways people interact with the material world is presented. This framework is employed as a lens into the social role and meaning the carvings played in the Dorset society. The examined assemblages were recovered from a series of Dorset settlement sites, mainly in house, midden, and burial contexts, providing a substantive case study through which variations and themes of carvings are studied. -

Infonorth Five Hundred Meetings of the Arctic Circle

ARCTIC VOL. 67, NO. 2 (JUNE 2014) P. 1 – 12 InfoNorth Five Hundred Meetings of the Arctic Circle by C.R. Burn SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES 1 AND 2 TABLE 1. List of meetings of the Arctic Circle.1 Special Meetings are in bold. Year Meeting Date Speaker2 Topic3 1947 1 12 December Flt. Lt. A.H. Tinker Establishment of weather stations at Eureka and Resolute Bay 1948 2 15 January Sgt. F.S. Farrar, RCMP Film: St Roch 3 16 February R.G. Madill, Flt. Lt. J.F. Drake North magnetic pole 4 18 March Lt. Col. A. Croft Operation Musk-ox 5 13 April H.M. Raup Botany, geology, and archaeology, Alaska Highway 6 25 May J.G. Wright Film: RMS Nascopie 7 20 August Picnic at the Jenness’s cottage 8 4 November C.S. Lord Mining in NWT 9 9 December P. Serson Operation Magnetic 1949 10 13 January B.J. Woodruff Geodetic Survey of Canada 11 10 February P.D. Baird Project Snow Cornice 12 10 March Cdr. D.C. Nutt, USNR Antarctica 13 14 April J.C. Wyatt Construction in the Arctic 14 12 May Mrs. T.H. Manning Travels in Hudson Bay and Foxe Basin 15 10 November Dr. J.C. Callaghan Experiences of a medical officer in the Arctic 16 8 December M.J. Dunbar Marine resources of the eastern Arctic 1950 17 12 January Flt. Lt. B. Hartman Search and rescue in the eastern Arctic 18 9 February A.E. Porsild Plant life 19 9 March D. Wilkinson NFB in the North 20 13 April T.H. -

Movements and Habitat Use of Muskoxen on Bathurst, Cornwallis

MOVEMENTS AND HABITAT USE OF MUSKOXEN (Ovibos moschatus) ON BATHURST, CORNWALLIS, AND DEVON ISLANDS, 2003-2006 Morgan Anderson1 and Michael A. D. Ferguson Version: 23 December 2016 1Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Box 209 Igloolik NU X0A 0L0 STATUS REPORT 2016-08 NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT WILDLIFE RESEARCH SECTION IGLOOLIK, NU i Summary Eleven muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) were fitted with satellite collars in summer 2003 to investigate habitat preferences and movement parameters in areas where they are sympatric with Peary caribou on Bathurst, Cornwallis, and Devon islands. Collars collected locations every 4 days until May 2006, with 4 muskoxen on Bathurst Island collared, 2 muskoxen collared on Cornwallis Island, and 5 muskoxen collared on western Devon Island. Only 5-29% of the satellite locations were associated with an estimated error of less than 150 m (Argos Class 3 locations). Muskoxen in this study used low-lying valleys and coastal areas with abundant vegetation on all 3 islands, in agreement with previous studies in other areas and Inuit qaujimajatuqangit. They often selected tussock graminoid tundra, moist/dry non-tussock graminoid/dwarf shrub tundra, wet sedge, and sparsely vegetated till/colluvium sites. Minimum convex polygon home ranges representing 100% of the locations with <150 m error include these movements between core areas, and ranged from 233 km2 to 2494 km2 for all collared muskoxen over the 3 years, but these home ranges include large areas of unused habitat separating discrete patches of good habitat where most locations were clustered. Several home ranges overlapped, which is not surprising, since muskoxen are not territorial. -

Exploration History and Mineral Potential of the Central Arctic Zn-Pb District, Nunavut KEITH DEWING,1 ROBERT J

ARCTIC VOL. 59, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 2006) P. 415– 427 Exploration History and Mineral Potential of the Central Arctic Zn-Pb District, Nunavut KEITH DEWING,1 ROBERT J. SHARP2 and TED MURARO3 (Received 23 March 2006; accepted in revised form 25 July 2006) ABSTRACT. Exploration in the central Arctic Zn-Pb District took place in five phases: 1) an initial exploration period (1960– 70), during which most surface showings on Cornwallis and Little Cornwallis islands were found; 2) a discovery period (1971– 79), during which the buried Polaris ore body was discovered and its feasibility and viability established, new showings were found farther afield, and many showings received limited drill testing; 3) the production period (1980–88), dominated by drilling at Polaris Mine; 4) an ore-replacement exploration period (1989–2001), during which showings close to Polaris were extensively drilled, showings on Cornwallis Island drill tested, and new showings found and drilled farther away; and 5) a reclamation period (2002–05), during which the infrastructure was removed and the mine site restored. Factors affecting the timing and rate of exploration were generally intrinsic to the region: 1) discovery of showings in 1960, 2) discovery of the Polaris ore body in 1971, 3) declining reserves between 1989 and 2002, 4) closure of the mine in 2002, 5) the short exploration season and difficult logistics, and 6) lack of competition. The external drivers of exploration were 1) oil-related exploration that led to the discovery of the Polaris showings, 2) the onset of regional exploration coinciding with spikes in the price of zinc, and 3) the surge in scientific interest in carbonate-hosted Zn-Pb deposits in 1967. -

Volume 29, 1981

_- c+:E Yol xxx no. I Mcrch t98l THE ARCTIC CIRCULAR VOL. XXX Published by the Arctic Circle March NO. I Ottawa, Canada 198 I CONTENTS Cover Picture: Northumberland House; from the sketchbooks of Dr. Maurice Haycock. See description page 6. PaRe No. All Around the Circle I Inuit Artists and Eskimo Art, by George Swinton 3 Northumberland House 6 Canadars Wild Rivers ............. 7 Draft Green Paper on Lancaster Sound 9 Northline l5 Polar Bear Pass Consultation Period Extended L5 Proposed Constitution Essential to Preserve and Strengtren Native Rights: Munro I5 First International Conference on the Discovery and History of the Boreal Polar Regions 16 The Northern Resources Conferences ........ 17 Northwest Territories Statistics Quarterly ................ 17 Northwest Territories Population Estimates, December 1980 ............. 17 ISBN: 0004 086X ALL AROUND THE CIRCLE Annual General MeetinR.20 Januarv 1981. Reports by the Treasurer, on the Annual tlominating Committee were given, and the following slate of executive and committee members was elected to serve for l98l: EXECUTIVE President Mr. A.C. David Terroux Past President Dr. Kenneth C. Maclure Vice President Professor Owen Dixon Secretary Miss Sally MacDonald Treasurer Dr. Thomas Frisch Editor Mrs. Nora Murchison Publication Mr. Stan A. Kanik COMMITTEE I 9E0-82 Mrs. Dorothy Brown Beckel I 980-82 Rev. Roger E. Briggs 198 l-83 Mr. Evan Browne 197 9-81 Dr. David R. Gray r97 9-8r Mrs. Alma Houston 198 l-83 Miss Helen M. Kerfoot I 98 0-82 Dr. Olav H. Ldken r97 9-8r Mrs. Isobel MacDonald 198 l-83 Mr. Norman J. MacPherson 198 l-83 Mr. -

A National Ecological Framework for Canada

A NATIONAL ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK FOR CANADA Written and compiled by: Ecological Stratification Working Group Centre for Land and Biological State of the Environment Directorate Resources Research Environment Conservation Service Research Branch Environment Canada Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada ---- Copies of this report and maps available from: Canadian Soil Information System (CanSIS) Centre for Land and Biological Resources Research Research Branch, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Ottawa, ON KIA OC6 State of the Environment Directorate Environmental Conservation Service Environment Canada Hull, PQ KIA OH3 Printed and digital copies of the six regional ecodistrict and ecoregion maps at scale of 1:2 million (Atlantic Provinces #CASOlO; Quebec #CASOll; Ontario #CAS012; Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta #CAS013; British Columbia and Yukon Territory #CASOI4; and the Northwest Territories #CASOI5); and associated databases are available from Canadian Soil Information System (CanSIS), address as above. co Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1996 Cat. No. A42-65/1996E ISBN 0-662-24107-X Egalement disponible en fran91is sous Ie titre Cadrc ecologiqllc national po"r Ie Canada Bibliographic Citation: Ecological Stratification Working Group. 1995. A National Ecological Framework for Canada. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Research Branch, Centre for Land and Biological Resources Research and Environment Canada, State of the Environment Directorate, Ecozone Analysis Branch, Ottawa/Hull. Report and national map at 1:7500 000 scale. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Acknowledgemenl<; v 1. Ecolo~cal Re~onalization in Canada 1 2. Methodology. .. .. 2 Map COlnpilation . .. 2 Levels of Generalization. .. 2 Ecozones 2 Ecoregions . 4 Ecodistricts 4 Data Integration. .. 6 3. The Ecological Framework 8 4. Applications of the Framework 8 Reporting Applications. -

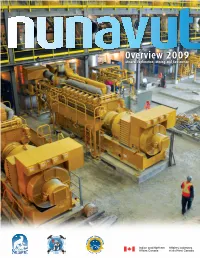

Exploration Overview 2009

2373_01_00_Layout 1 07/01/10 9:17 PM Page 1 2373_01_00_Layout 1 07/01/10 9:29 PM Page 2 (Above) Qikiqtarjuaq, August 2009 COURTESY OF GN-EDT Contents: Acknowledgements Land Tenure in Nunavut........................................................................................................3 The 2009 Exploration Overview Indian and Northern Affairs Canada....................................................................................4 was written by Karen Costello (INAC), Andrew Fagan Government of Nunavut........................................................................................................6 (consultant) and Linda Ham (INAC) with contributions from Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. ........................................................................................................8 Don James (CNGO), Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office ...................................................................................10 Keith Morrison (NTI) and Eric Prosh (GN). Summary of 2009 Exploration Activities Front cover photo: Kitikmeot Region .........................................................................................................20 Installation of power plants, Kivalliq Region .............................................................................................................41 Meadowbank Mine COURTESY OF AGNICO-EAGLE MINES LIMITED Qikiqtaaluk/Baffin Region...........................................................................................61 Back cover photo: Index .....................................................................................................................................75 -

Synopsis of the Polaris Zn-Pb District, Canadian Arctic

SYNOPSIS OF THE POLARIS ZN-P B DISTRICT , C ANADIAN ARCTIC ISLANDS , N UNAVUT KEITH DEWING 1, R OBERT J. S HARP 2 , AND ELIZABETH TURNER 3 1. Geological Survey of Canada, 3303-33rd Street NW, Calgary, Alberta T2L 2A7 2. Trans Polar Geological, 60 Hawkmount Heights NW, Calgar,y Alberta T3G 3S5 3. Department of Earth Science, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, P3E 2C6 Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Abstract The Polaris Mine was a Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) deposit hosted in dolomitized Middle Ordovician lime - stone. Total production was 20.1 Mt at 13.4% Zn and 3.6% Pb. There are about 80 showings in the district, which stretches from Somerset Island to the Grinnell Peninsula. There are two deposit types in the Polaris District: 1) struc - turally controlled, carbonate-hosted Zn-Pb-Fe deposits typical of MVT deposits, and 2) structurally and stratigraphi - cally controlled, carbonate-hosted Cu deposits enriched by later supergene removal of Fe and S. Mineralization is paragenetically simple, with sphalerite and galena as the ore minerals, and with dolomite and mar - casite as the main gangue minerals. The deposits formed from brines at about 90 to 100°C. The age of the mineraliza - tion is constrained to post-Late Devonian folding and may be associated with the last stages of the Ellesmerian Orogeny or the opening of the Sverdrup Basin. Copper-rich mineralization is known from four showings, is associated with zinc- lead mineralization and is confined to a single interval in the Silurian. The metallogenic model for Polaris invokes a source of metal ions within the stratigraphic column since strontium shows no indication of basement involvement. -

Aardvark Archaeology 2004 Archaeological Investigations at Ilhavo Park (Cjae-53) Duckworth Street and Plymouth Road, St

Provincial Archaeology Office July 8, 2020 Aardvark Archaeology 2004 Archaeological Investigations at Ilhavo Park (CjAe-53) Duckworth Street and Plymouth Road, St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador. 03.51 2004 Stage 1 HRA of the St. John’s Harbour Clean-Up. Part 1: Water Street, from Hutchings Street to Waldegrave Street. 2005 HRIA for the East Coast Hiking Trail Interpretation on the Mount, Renews, Newfoundland. 05.18 2005 Stage 1 HRIA of the Mortier Bay-North Atlantic Marine Service Centre, Powers Cove, NL. 05.53 2005 HRIA of the Murphy’s Cove Development Project. Collier Point, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador. 05.60 2005 HRIA of the South Brook Park Site (DgBj-03). 05.58 (on CD) 2006 Archaeological Monitoring of the 2006 Ferryland Beach Stabilization. 06.01 2006 Stage 1 HROA of 331 Water Street, St. John’s, NL. 2006 Archaeological Assessment of the Mockbeggar Plantation Provincial Historic Site Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador. 06.50 2006 Beneath the Big Store: Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of the Mockbeggar Plantation Provincial Historic Site Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador. 06.50.01 2007 HRIA of Berry Island, Point Leamington Newfoundland and Labrador. 07.21 2008 Archaeological Assessment of the Bridge House Property (DdAg-03) Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador. 08.11 Adams, W. P. & J. B. Shaw 1967 Studies of Ice Cover on Knob Lake, New Québec. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 11(22), p. 88-96. Adney, Edwin Tappan & Howard I. Chapelle 1964 The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America. AECOM 2012 Stage 2 Historical Impact Assessment 2012 Strange Lake-Quest Rare Minerals Project Field Survey Results Update. -

Tab 9 Peary Caribou and Muskox Aerial Survey on Bathurst Island

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: X Decision: Issue: Update on abundance and distribution of Peary caribou and muskox on the Bathurst Island Complex following aerial survey in May 2013. Background: Peary caribou on the Queen Elizabeth Islands are subject to periodic die-offs when ground-fast ice makes forage unavailable. On the Bathurst Island Complex, a series of bad winters from 1994 to 1997 caused the population to rapidly decline from 3155 caribou in 1994 to a minimum count of 76 in 1997. Muskox also declined over this period. The Bathurst Island Complex, as well as Cornwallis and Little Cornwallis Islands, were surveyed by the Nunavut Department of Environment in 2001 and 2002, with a population estimate of 187 Peary caribou (95% confidence interval 104-330) and minimum count of 82 muskoxen. No caribou were reported on Cornwallis or Little Cornwallis, and the minimum count of muskox was 18. Resolute Bay hunters reported seeing more caribou and muskox and requested a survey be flown to update the population estimate. We flew 42 hours by Twin Otter between May 13 and May 27. Poor weather dictated that north and south Bathurst Island were flown with 10-km transect spacing instead of 5-km. Cornwallis and Little Cornwallis were also flown at 10-km transect spacing. Current Status The May 2013 survey estimated 1483 ± 387 (95% CI) Peary caribou (including 11- month-old calves), substantially more than the May 2001 estimate of 187 (104-330, 95% CI). These results suggest that the caribou population on the BIC is recovering from the late 1990s die-off (Figure 1). -

Committee Bay Drift Prospecting

7th Annual Nunavut Mining Symposium October 6th – 8th, 2003 Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office Past, Present and Future Advancing sustainable development through collaborative geoscience research H. Sandeman, E. Little, R.Sherlock, E. Turner C. Gilbert and J. Taylor Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office (C-NGO) Established 1999 Partnership, regional office of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) Natural Resources Canada (NRcan), Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Government of Nunavut Department of Sustainable Development (GN-DSD) Staff include 1 Research Manager (vacant), 4 Research Scientists, 2 GIS specialists, 1 administrative assistant and rotating casual staff and students “Geoscience in Support of Sustainable Development” Arctic Zinc Nanisivik Hope Bay Central Baffin Meadowbank Committee Bay Projects 2000-2004 Central Baffin Integrated Geoscience Project . Integrated, multi-agency field based project targeting the northern, upper-plate margin of the Paleoproterozoic Trans-Hudson Orogen on central Baffin Island Objectives . Bedrock mapping . 3D architecture Iqaluit . Thermochronological and petrological evolution . Tectonic setting and metallogenisis . Understand the progressive amalgamation of NE Laurentia . Surficial mapping . Ice margin mapping in relation to climate change . Development of an integrated digital database . Collaboration with University of Calgary, University of Saskatchewan, Queen’s University, Carleton University, McGill University, Dalhousie 200 km University, Polar Continental Shelf Project +7Graduate theses . Funded through C-NGO, GSC, PCSP +5 BSc theses Central Baffin Integrated Geoscience Project glaciology Bedrock and surficial mapping And MUCH MORE…! http://gsc-cgd.nrcan.gc.ca/baffin4d/ 3D modelling Committee Bay Integrated Geoscience Project http://gsc-cgd.nrcan.gc.ca/committee_bay/Committee.html . Collaborative, C-NGO – GSC integrated geoscience project providing new bedrock, surficial and aeromagnetic maps and upgrading geoscience information . -

NEAS Port Codes

LIST OF PORTS AND/OR DESTINATIONS LISTE DES PORTS ET/OU DESTINATIONS(Updated: March 25, 2020) Code Code Code Name / Nom Name / Nom Name / Nom NEAS NEAS NEAS Akulivik AKU Grande Anse GRA Naujaat (Repulse Bay) NAU Arctic Bay ARB Grise Fiord GRI Nottingham Island NOI Arviat ARV Gros Cacouna GRO Padloping Island PAD Aupaluk AUP Igloolik IGL Pangnirtung PAN Baie Comeau BCO Inukjuak INU Pond Inlet PON Baker Lake BAK Iqaluit IQA Port Cartier PCA Bécancour BEC Ivujivik IVU Puvirnituq PUV Big Bay BIG Jackson Inlet JAC Qikiqtarjuaq QKQ Brevoort BRE Jenny Lind Island JLI Quaqtaq QUA Byron Bay BYB Kangiqsualujjuaq KAL Quebec QUE Cambridge Bay CAM Kangiqsujuaq KAQ Rankin Inlet RAN Cape Dyer DYE Kivitoo KIV Resolute Bay RES Cape Henrietta Maria HEN Kugaaruk KGA Resolution Island RSI Cape Hooper HOO Kangirsuk KAN Roche Bay ROC Cape Kakiviak CKA Kangok Fiord GOK Saglek SAG Cape Kiglapait KIG Kimmirut KIM Salluit SAL Cape Mercy MER Kinngait (Cape Dorset) DOR Sanikiluaq SAN Cape Young YOU Kugluktuk KGL Sanirajak (Hall Beach) HAL Cartwright CAR Kuujjuaq KUU Sept-Iles SIL Chesterfield Inlet CHE Kuujjuarapik KIK Ste-Catherine SCA Churchill CHU Les Mechins MEC Steensby Inlet STE Clyde River CLY Little Cornwallis Island LCI Taloyoak TAL Contrecoeur CON Loks Land LOK Tasiujaq TAS Coral Harbour COR Longstaff Bluff LSB Thule THU Deception Bay DBA Matane MAT Trois-Rivieres TRV Ekalugad EKA Matheson Point MAP Umiujaq UMI Eureka EUR Milne Inlet MIL Valleyfield VAL Gaspé GAS Montreal MTL Whale Cove WHA Gjoa Haven GJO Nain NAI Winisk WIN Goose Bay GOO Nanisivik NAN 1-877-225-6327 • NEAS.ca.