The Shetland Bus by David Howarth User Search Limit Reached - Please Wait a Few Minutes and Try Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Rowland Kenney and British Propaganda in Norway: 1916-1942

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository ROWLAND KENNEY AND BRITISH PROPAGANDA IN NORWAY: 1916-1942 Paul Magnus Hjertvik Buvarp A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2016 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/8647 This item is protected by original copyright Rowland Kenney and British Propaganda in Norway: 1916-1942 Paul Magnus Hjertvik Buvarp This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 18 September 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, ……, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately ….. words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in [month, year] and as a candidate for the degree of …..…. in [month, year]; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between [year] and [year]. (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, …..., received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of [language, grammar, spelling or syntax], which was provided by …… Date …… signature of candidate ……… 2. -

The Impact of External Shocks Upon a Peripheral Economy: War and Oil in Twentieth Century Shetland. Barbara Ann Black Thesis

THE IMPACT OF EXTERNAL SHOCKS UPON A PERIPHERAL ECONOMY: WAR AND OIL IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SHETLAND. BARBARA ANN BLACK THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY July 1995 ProQuest Number: 11007964 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007964 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis, within the context of the impact of external shocks on a peripheral economy, offers a soci- economic analysis of the effects of both World Wars and North Sea oil upon Shetland. The assumption is, especially amongst commentators of oil, that the impact of external shocks upon a peripheral economy will be disruptive of equilibrium, setting in motion changes which would otherwise not have occurred. By questioning the classic core-periphery debate, and re-assessing the position of Shetland - an island location labelled 'peripheral' because of the traditional nature of its economic base and distance from the main centres of industrial production - it is possible to challenge this supposition. -

Total E&P Norge AS

ANNUAL REPORT TOTAL E&P NORGE AS E&P NORGE TOTAL TOTAL E&P NORGE AS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CONTENTS IFC KEY FIGURES 02 ABOUT TOTAL E&P NORGE 05 BETTER TOGETHER IN CHALLENGING TIMES 07 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ REPORT 15 INCOME STATEMENT 16 BALANCE SHEET 18 CASH FLOW STATEMENT 19 ACCOUNTING POLICIES 20 NOTES 30 AUDITIOR’S REPORT 31 ORGANISATION CHART IBC OUR INTERESTS ON THE NCS TOTAL E&P IS INVOLVED IN EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION O F OIL AND GAS ON THE NORWEGIAN CONTINENTAL SHELF, AND PRODUCED ON AVERAGE 242 000 BARRELS OF OIL EQUIVALENTS EVERY DAY IN 2014. BETTER TOGETHER IN CHALLENGING TIMES Total E&P Norge holds a strong position in Norway. The Company has been present since 1965 and will mark its 50th anniversary in 2015. TOTAL E&P NORGE AS ANNUAL REPORT TOTAL REVENUES MILLION NOK 42 624 OPERATING PROFIT MILLION NOK 22 323 PRODUCTION (NET AVERAGE DAILY PRODUCTION) THOUSAND BOE 242 RESERVES OF OIL AND GAS (PROVED DEVELOPED AND UNDEVELOPED RESERVES AT 31.12) MILLION BOE 958 EMPLOYEES (AVERAGE NUMBER DURING 2013) 424 KEY FIGURES MILLION NOK 2014 2013 2012 INCOME STATEMENT Total revenues 42 624 45 007 51 109 Operating profit 22 323 24 017 33 196 Financial income/(expenses) – net (364) (350) (358) Net income before taxes 21 959 23 667 32 838 Taxes on income 14 529 16 889 23 417 Net income 7 431 6 778 9 421 Cash flow from operations 17 038 15 894 17 093 BALANCE SHEET Intangible assets 2 326 2 548 2 813 Investments, property, plant and equipment 76 002 67 105 57 126 Current assets 7 814 10 506 10 027 Total equity 15 032 13 782 6 848 Long-term provisions -

Rowland Kenney and British Propaganda in Norway: 1916-1942

ROWLAND KENNEY AND BRITISH PROPAGANDA IN NORWAY: 1916-1942 Paul Magnus Hjertvik Buvarp A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2016 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/8647 This item is protected by original copyright Rowland Kenney and British Propaganda in Norway: 1916-1942 Paul Magnus Hjertvik Buvarp This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 18 September 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, ……, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately ….. words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in [month, year] and as a candidate for the degree of …..…. in [month, year]; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between [year] and [year]. (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, …..., received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of [language, grammar, spelling or syntax], which was provided by …… Date …… signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of ……… in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Molde Og Romsda L Il~Rigstiden 1940

N ils Parelius: Molde og Romsda l i l~rigstiden 1940 - 1945 Try kt med støtte fra Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum og Møre og Romsdal fylke. Nils Parelius Molde og Romsdal i krigstiden / 1940 - 1945 En. bibliografi Med noen. utdrag fra bøkene Utgitt av Romsdalsmuseet «Kongen Omslagetog Kronprinsen viser et ved utsnitt Molde av 1940> Axel Revolds maleri (Tilh�rer Oslo Handelsstands Forening) Klisj eene velvillig utlant av H. Aschehoug & Co. E. K. Hansens trykkeri Molde 1970 Mens de spilte gamle stykker i vår blodige april , /!ertes teppet for et ann et, vilt og ukjent skuespill, aldr i øvet, aldri prøvet , jagende fra sted til sted - det var Norges skjebnedrama . Nordah l Grieg. Innledning Bibliografien tar sikte på å registre re den litt erat ur som fore ligger om Molde og Romsdal i krigstiden 9. april 1940 til 8. mai 1945. Litteratur hvor Molde og Romsdal bare nevnes uten nær mere omtale, er ikke tatt med. Det samme prinsipp er fulgt når det gjelder lokale publik asjoner som innskr enker seg til å nevn e krigstiden. Bibliografien omfatter ikke avisartikler, unntatt i de tilfelle hvor de er inntatt i samleverker . I ett tilf elle har en imid ledtid funn et grun n t il å ta med en større serie avisartikler . Så vidt mulig er også billedstoff angitt. Molde og Rom sdal har fått en forhol dsvis bred plass i litte rat uren om kri gsbegiven hetene i 1940. Det skyldes for det første den militære rolle distriktet kom til å spille. Alt 8. april kom Romsdalsk ysten i bren npunkt et. -

Our New E-Commerce Enabled Shop Website Is Still Under Construction

Our new e-commerce enabled shop website is still under construction. In the meantime, to order any title listed in this booklist please email requirements to [email protected] or tel. +44(0)1595 695531 2009Page 2 The Shetland Times Bookshop Page 2009 2 CONTENTS About us! ..................................................................................................... 2 Shetland – General ...................................................................................... 3 Shetland – Knitting .................................................................................... 14 Shetland – Music ........................................................................................ 15 Shetland – Nature ...................................................................................... 16 Shetland – Nautical .................................................................................... 17 Children – Shetland/Scotland..................................................................... 18 Orkney – Mackay Brown .......................................................................... 20 Orkney ...................................................................................................... 20 Scottish A-Z ............................................................................................... 21 Shetland – Viking & Picts ........................................................................... 22 Shetland Maps .......................................................................................... -

Island Geographies, the Second World War Film and the Northern Isles of Scotland

\ Goode, I. (2018) Island geographies, the Second World War film and the Northern Isles of Scotland. In: Holt, Y., Martin-Jones, D. and Jones, O. (eds.) Visual Culture in the Northern British Archipelago: Imagining Islands. Series: British art: histories and interpretations since 1700. Routledge: London, pp. 51-68. ISBN 9780815374275 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/149336/ Deposited on 06 October 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 3. Island Geographies, the Second World War film and the Northern Isles of Scotland Ian Goode A visitor to the Northern Isles off the tip of Scotland can't help but recognize the importance of the Second World War to their history. Yet this group of islands rarely feature in the common representations of the war produced by feature films from Britain, including those which, occasionally, involve Hollywood studios. The films that typically populate the schedules of daytime television in Britain give little indication of the extent of the role played by the Northern Isles in the war. One might argue that, in the British cinematic imaginary of World War II, the contribution of the Northern Isles to the war effort suffers from something of a similar lack of recognition to that of much of the then British Empire. There are, though, a small group of war films that do reveal the importance of these islands in the war and warrant further discussion. -

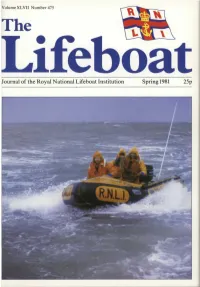

Lifeboat Institution Spring 1981T 25P

Volume XLVII Number 475 The LifeboaJournal of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution Spring 1981t 25p mt \btur needs are simple "V Our many hundreds of industrial customers include the Dutch. German. Spanish and Swiss life boat services and all Dutch sea pilots as well as all UK TV companies and most other public services Functional "Airflow" Jacket and Overtrousers Royal National Life-Boat Institution "...in 1971 the RNLI adopted Functional for Offshore Stations. The clothing has been well received by our crews who operate in severe conditions for prolonged periods." The best possible protect ion Kevin MacDonnell in 'Photography' "The astonishing thing is the price... in all weathers incredibly well made out of top grade materials...the best clothing bargain encountered for years" Derek Agnew, Editor of 'En Route' Magazine of the Caravan Club "For the caravanner who wants only the CTIONAL best I thoroughly recommend this range" Tom Waghorn in 'Climber & Rambler' "...1 wore the (Lightweight Walking) Functional make a range of activity clothing in six shades, Overtrousers for six hours of continuous wind-blown rain and they performed including clothing for seagoing in Orange, magnificently in these appalling conditions" intended for the professional seaman, Billy Boddy in 'Motor Sport' for life-boat services, and for ocean racing: "...top class conscientiously made...bad- jacket, high-chest overtrousers, headgear weather keep-warm clothing...clearly the best possible for outdoor work and play.. .i Clothing that is waterproof and windproof and good to look ai should comfort you for a long time in the Clothing in which you can work or enjoy your leisure, worst of weather" comfortable at all times, Verglas in 'Motoring News' "protected from...the arctic cold...snug and and with a minimum of condensation warm in temperatures even as low as minus Sold only direct to user, industrial or personal 40°C...The outer jacket makes most rally jackets look like towelling wraps...all weather protection in seconds.. -

Importance of Wireless Connectivity in Offshore Digitalisation Industry Pain Point: Connectivity How Do We Address It?

Importance of Wireless Connectivity In Offshore Digitalisation Industry Pain Point: Connectivity How do we address it? Offshore Offshore International Infrastructure 4G LTE Carrier Magnus Trondheim Eider Thistle Snorre A Tern North Cormorant Gullfaks C Cormorant A Brent Gullfaks A Heather Ninian Kvitebjørn Stockholm Clair Ridge N Alwyn Kollsnes Oslo Veslefrikk Troll A The Martin Linge Oseberg Brage Glen Lyon Kraken Norway Bruce Tveiten Tampnet North Sea Beryl B Mariner Heimdal Kårstø Beryl A Alvheim Jotun A Green Mountain Gryphon Ringhorne Infrastructure Grane Stavanger Harding Ivar Aasen Egersund Stølen Brae E Gudrun Edv.Grieg Brae B Gina Lista Brae A Krog Claymore Piper B Sleipner Tartan Tiffany Balmoral Draupner Bulbjerg Scott Andrew Alba Armada YME Britannia Forties B Aberdeen Forties Unity Everest Forties C Scotland Nelson Culzean Montrose Lomond Ula Denmark Kittiwake Erskine Gannet Gyda ETAP Triton Elgin/Franklin King Lear Shearwater Judy Copenhagen Jade Ekofisk USA Clyde Esbjerg Edinburgh Fulmar Valhall Syd Arne The North Sea Cygnus Murdoch Hamburg LEGEND: Hornsea Leeds Tampnet LOS Germany Optical Fiber England Tampnet POP Lowestoft Netherlands Amsterdam USA Slough Belgium London France 4G/LTE Marine Coverage 4G/LTE Marine Coverage North Sea Baton 4G/LTE Coverage GoM Rouge Data Pascagoula . Existing (outlined in blue) Cable Landing Center Station . Planned (outlined in yellow) . Exclusive access to BP’s Deepwater Fiber (white line offshore) Freeport Cable Landing Station Houston Data Center ~250 000 km² Tampnet Core Carrier Network -

Ian Herrington November 2002

DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY, LEICESTER THE SPECIAL OPERATIONS EXECUTIVE IN NORWAY 1940-1945: POLICY AND OPERATIONS IN THE STRATEGIC AND POLITICAL CONTEXT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES BY IAN HERRINGTON June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract.……………………………………………………………………..i Acknowledgements.………...……………………………………………….ii Abbreviations.……..………………………………………………………. iii Maps………..…………………………………………………………..viii-xii CHAPTERS Introduction……..… ………………………………………………….1 1. The Formation of SOE and its Scandinavian Section: A New Strategic Tool and a Nordic Opportunity …………………………………….. .26 2. SOE’s Policy in Norway 1940-1945: The Combination of Short and Long-Term Aims …………………………………….……………... 55 3. SOE and the Norwegian Government and its Military Authorities 1940-1945: Control through Collaboration………….………….……84 4. SOE and the Military Resistance in Norway 1940-1945: Direction, Separation and finally Partnership…………………………………..116 5. SOE and the other New Organisations Operating in Norway 1940- 1945: A Military Alliance..………………………………………….146 6. SOE and the Regular Armed Forces Operating in Norway 1940-1945: an Unexpected Partnership…………………………………….……185 7. SOE Operations in Norway 1940-1944: The Combination of Sabotage and the Organisation of a Clandestine Army ……………………….221 8. SOE and the Liberation of Norway 1944-1945: Operations in the Shadow of Overlord....……………………………………………..257 Conclusion…………………………………………………………..289 APPENDICES Appendix A: List -

Telavåg I Tid Og Rom Erindringen Om Et Krigsherjet Fiskerisamfunn

Telavåg i tid og rom Erindringen om et krigsherjet fiskerisamfunn Mastergradsoppgave i historie Eirik Gurandsrud Høgskolen i Bergen – Universitetet i Bergen Vår 2005 Innhold Forord s. 5 Kapittel 1 Innledning s. 6 1.1 Tema og problemstilling s. 6 1.1.1 Problemstilling s. 7 1.2 Kilder s. 8 1.2.1 Krigslitteratur s. 8 1.2.2 Aviser og radio s. 9 1.2.3 Dikt, memoarer og skjønnlitteratur s. 10 1.2.4 Muntlige kilder s. 10 1.2.5 Kilder knyttet til Nordsjøfartmuseet s. 11 1.3 Metode s. 11 Kapittel 2 Historie og offentlighet – teoretisk grunnlag s. 13 2.1 Maurice Halbwachs: Kollektiv erindring s. 13 2.1.1 Hvordan kollektiverindring oppstår s. 13 2.1.2 Autobiografisk minne og historisk minne s. 15 2.1.3 Kollektiv erindring i tid og rom s. 16 2.2 Jan Assmann: Kommunikativ og kulturell erindring s. 16 2.3 Pierre Nora: Lieux de memoire s. 19 2.4 Historiekultur s. 20 2.5 Okkupasjonstiden som kollektiv erindring s. 21 2.5.1 Den norske okkupasjonstiden som kollektiv erindring s. 21 2.5.2 Den danske okkupasjonstiden som kollektiv erindring s. 25 2 2.6 Museet og dets presentasjon av fortiden s. 27 2.6.1 Hva er et museum? s. 27 2.6.2 Historieformidling i museet s. 29 2.7 Teori og praksis s. 30 Kapittel 3 Kilder og forskning om Telavåghistorien s. 32 3.1 Kilder til Telavåghistorien s. 32 3.1.2 Skriftlige kilder s. 32 3.1.3 Muntlige kilder s. 33 3.2 Forskningsfronten s.