1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Notes De L'ifri N° 4 the United States and the European Security

les notes de l’ifri n° 4 série transatlantique The United States and the European Security and Defense Identity in the New NATO Les États-Unis et l’Identité européenne de sécurité et de défense dans la nouvelle OTAN Philip Gordon Senior Fellow for US Strategic Studies and Editor of Survival, International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS, London) 1998 Institut français des relations internationales Le programme transatlantique est organisé avec le concours du German Marshall Fund of the United States. Cette publication a également reçu le soutien de la Délégation aux affaires stratégiques du ministère de la Défense L’Ifri est un centre de recherche et un lieu de débats sur les grands enjeux politiques et économiques internationaux. Dirigé par Thierry de Montbrial depuis sa fondation en 1979, l’Ifri a succédé au Centre d’études de politique étrangère créé en 1935. Il bénéficie du statut d’association reconnue d’utilité publique (loi de 1901). L’Ifri dispose d’une équipe de spécialistes qui mène des programmes de recherche sur des sujets politiques, stratégiques, économiques et régionaux, et assure un suivi des grandes questions internationales. © Droits exclusivement réservés, Ifri, Paris, 1998 ISBN 2-86592-061-5 ISSN 1272-9914 Ifri - 27, rue de la Procession - 75740 Paris Cedex 15 - France Tél.: 33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax : 33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Contents Les États-Unis et l’IESD dans la nouvelle OTAN (résumé en français) . 5 The United States and ESDI in the New NATO (summary in French) Introduction . 11 Introduction American Unilateralism After the Cold War . -

Joint Force Quarterly Hans Binnendijk Patrick M

0115Cover1 8/4/97 11:01 AM Page 1 JFJOINTQ FORCE QUARTERLY RMA Essay Contest Interservice Competition NATO, EUROPEAN SECURITY,AND BEYOND Military Support to Spring The Nation 97 The Son Tay Raid A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL 0215Cover2 8/5/97 7:49 AM Page C2 Victory smiles upon those who anticipate the changes in the character of war, not upon those who wait to adapt themselves after the changes occur. —Guilio Douhet Cov 2 JFQ / Spring 1997 0315Prelims 8/4/97 1:28 PM Page 1 JFQ AWord from the I NATO’s consultative mechanisms have been a positive force for stability on the Continent and were central to the solution of bilateral problems among its Chairman members I NATO forces, policies, and procedures proved to be an essential and irreplaceable foundation for the coalition’s success in Operation Desert Storm ight years ago, as the Berlin Wall crum- I NATO forces from 15 allied nations—backed by bled and the Cold War began to fade, 22 other countries, including Russia—are keeping order in Bosnia-Herzegovina today, a peace brought about by two themes dominated media reports the force of NATO arms. about Europe. First, many pundits ar- Egued that while our hearts might remain in Eu- In the future, Europe will remain a center of rope our central strategic and economic interests wealth, democracy, and power. For the United would lie elsewhere in the future. For some, our States, it will remain a region of vital interest. Ac- focus would be primarily on the Middle East, for cording to our national security strategy, “Our ob- others on Latin America, and for still others on jective in Europe is to complete the construction the Asia-Pacific region. -

International Military Staff, Is to Provide the Best Possible C3 Staff Executive Operations, Strategic Military Advice and Staff Support for the Military Committee

Director General of IMS Public Affairs & Financial Controller StratCom Executive Coordinator Advisor Legal Office HR Office NATO Office Support Activities on Gender Perspectives SITCEN Cooperation NATO Intelligence Operations Plans & Policy & Regional Logistics Headquarters Security & Resources C3 Staff Intelligence Major Operation Strategic Policy Partnership Concepts Logistics Branch Executive Production Branch Alpha & Concepts & Policy Branch Coordination Office Branch Intelligence Policy Joint Operations Nuclear Special Partnerships Medical Branch Information Services Branch & Plans Branch & CBRN Defence Branch Branch Education Training Defence and Regional Partnerships Plans, Policy & Exercise & Evaluation Force Planning Armaments Branch Branch Branch Architecture Branch Air & Missile Infrastructure & Spectrum & C3 Defence Branch Finance Branch Infrastructure Branch Operations, Manpower Branch Requirements, & Plans Branch NATO Defence Information Assurance Consists of military/civilian staff from member nations. Manpower & Cyber Defence Personnel work in international capacity for the common interest of the Alliance. Audit Authority Branch www.nato.int/ims e-mail :[email protected] Brussels–Belgium 1110 HQ, NATO Office,InternationalMilitaryStaff, Affairs the Public For moreinformationcontact: NATO HQ. NATO and the moveto thenew NATO are adaptedtoreflect Future ‘ways ofworking’ changes are not it likely, will be important that the IMS is reconfigured and its a review of the IMS Summit, Chicago the was at direction initiated. Government and State While of Heads major the Following structural and organizational respected andthatistotallyfreefromdiscriminationprejudice. is individual each which in environment an in communication open and initiative resilience, for need the and learning continuous promote also They commitment. first, Mission always.’ Our peopleThe workIMS with professionalism,team integrityembraces and the principles and values enshrined Values in ‘People decisiveness andpride. -

NATO 20/2020: Twenty Bold Ideas to Reimagine the Alliance After The

NATO 2O / 2O2O TWENTY BOLD IDEAS TO REIMAGINE THE ALLIANCE AFTER THE 2020 US ELECTION NATO 2O/2O2O The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. The Scowcroft Center’s Transatlantic Security Initiative brings together top policymakers, government and military officials, business leaders, and experts from Europe and North America to share insights, strengthen cooperation, and develop innovative approaches to the key challenges facing NATO and the transatlantic community. This publication was produced in partnership with NATO’s Public Diplomacy Division under the auspices of a project focused on revitalizing public support for the Alliance. NATO 2O / 2O2O TWENTY BOLD IDEAS TO REIMAGINE THE ALLIANCE AFTER THE 2020 US ELECTION Editor-in-Chief Christopher Skaluba Project and Editorial Director Conor Rodihan Research and Editorial Support Gabriela R. A. Doyle NATO 2O/2O2O Table of Contents 02 Foreword 56 Design a Digital Marshall Plan by Christopher Skaluba by The Hon. Ruben Gallego and The Hon. Vicky Hartzler 03 Modernize the Kit and the Message by H.E. Dame Karen Pierce DCMG 60 Build Resilience for an Era of Shocks 08 Build an Atlantic Pacific by Jim Townsend and Anca Agachi Partnership by James Hildebrand, Harry W.S. Lee, 66 Ramp Up on Russia Fumika Mizuno, Miyeon Oh, and by Amb. -

Dod Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9

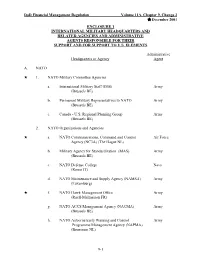

DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9, Change 2 December 2001 ENCLOSURE 1 INTERNATIONAL MILITARY HEADQUARTERS AND RELATED AGENCIES AND ADMINISTRATIVE AGENTS RESPONSIBLE FOR THEIR SUPPORT AND FOR SUPPORT TO U.S. ELEMENTS Administrative Headquarters or Agency Agent A. NATO 1. NATO Military Committee Agencies a. International Military Staff (IMS) Army (Brussels BE) b. Permanent Military Representatives to NATO Army (Brussels BE) c. Canada - U.S. Regional Planning Group Army (Brussels BE) 2. NATO Organizations and Agencies a. NATO Communications, Command and Control Air Force Agency (NC3A) (The Hague NL) b. Military Agency for Standardization (MAS) Army (Brussels BE) c. NATO Defense College Navy (Rome IT) d. NATO Maintenance and Supply Agency (NAMSA) Army (Luxemburg) f. NATO Hawk Management Office Army (Ruell-Malmaison FR) g. NATO ACCS Management Agency (NACMA) Army (Brussels BE) h. NATO Airborne Early Warning and Control Army Programme Management Agency (NAPMA) (Brunssum NL) 9-1 DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9, Change 2 December 2001 Administrative Headquarters or Agency Agent i. NATO Airborne Early Warning Force Command Army (Mons BE) j. NATO Airborne Early Warning Main Operating Base Air Force (Geilenkirchen GE) k. NATO CE-3A Component Air Force (Geilenkirchen GE) l. NATO Research and Technology Organization (RTO) Air Force (Nueilly-sur-Seine FR) l. NATO School Army (Oberammergau GE) m. NATO CIS Operating and Support Agency (NACOSA) Army (Glons BE) n. NATO Communication and Information Systems School Navy (NCISS) (Latina, IT) o. NATO Pipeline Committee (NPC) Army (Glons BE) p. NATO Regional Operating Center Atlantic Navy (ROCLANT)/NACOSA Support Element (NSE) West (Oeiras PO) 3. -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

The Maritime Dimension of Csdp

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES OF THE UNION DIRECTORATE B POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY THE MARITIME DIMENSION OF CSDP: GEOSTRATEGIC MARITIME CHALLENGES AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION Abstract The global maritime security environment is in the midst of an important transformation, driven by a simultaneous intensification of global maritime flows, the growing interconnectedness of maritime regions, the diffusion of maritime power to emerging powers, and the rise of a number of maritime non-state actors. These changes are having a profound impact on the maritime security environment of the EU and its member states and require an upgrading of the maritime dimension of the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). This study analysis the impact that the changing maritime security context is having on the EU’s maritime neighbourhood and along the EU’s sea lines of communications (SLOCs) and takes stock of the EU’s existing policies and instruments in the maritime security domain. Based on this analysis, the study suggests that the EU requires a comprehensive maritime security strategy that creates synergies between the EU’s Integrated Maritime Policy and the maritime dimension of CSDP and that focuses more comprehensively on the security and management of global maritime flows and sea-based activities in the global maritime commons. EP/EXPO/B/SEDE/FWC/2009-01/Lot6/21 January 2013 PE 433.839 EN Policy Department DG External Policies This study was requested by the European Parliament's Subcommittee on Security and -

Thomas L. Baptiste, Lieutenant General, United States Air Force

Thomas L. Baptiste, Lieutenant General, United States Air Force (Ret) President/Executive Director, National Center for Simulation Partnership III, 3039 Technology Parkway, Suite 213, Orlando, FL 32826 Lt. Gen. Thomas L. Baptiste completed his 34 year military career as the Deputy Chairman, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Military Committee, Brussels, Belgium. The NATO Military Committee is the highest military authority in NATO and provides direction and advice on military policy and strategy to the North Atlantic Council, guidance to the NATO strategic commanders, and support to the development of strategic concepts for the Alliance. In this role, Lt Gen (Ret) Baptiste also served as the second most senior military advisor to the NATO Secretary General. Lt Gen (Ret) Baptiste graduated from California State University, Chico, CA in June 1973 and earned a Graduate Degree from Golden Gate University, San Francisco, CA in 1986. Following commissioning from the Officer Training School, he was initially trained as a Navigator/Weapons Systems Officer and assigned to the F-4 in 1974. After one overseas operational tour he was competitively selected for Undergraduate Pilot Training and returned to the F-4 as a Pilot in 1978. In 1981, Lt Gen (Ret) Baptiste was handpicked to become part of the initial cadre of Instructor Pilots to stand-up the F-16 Training Wing at MacDill AFB, Tampa, FL. Several other F-16 assignments followed including Commander, 72nd Fighter Training Squadron and Commander 52nd Operations Group. During two staff assignments in Washington D.C., he served as: the Director of Operations, Defense Nuclear Agency, and as the Assistant Deputy Director, International Negotiations, Directorate of Plans and Policy (J-5), the Joint Staff in the Pentagon. -

NATO Summit Guide Brussels, 11-12 July 2018

NATO Summit Guide Brussels, 11-12 July 2018 A stronger and more agile Alliance The Brussels Summit comes at a crucial moment for the security of the North Atlantic Alliance. It will be an important opportunity to chart NATO’s path for the years ahead. In a changing world, NATO is adapting to be a more agile, responsive and innovative Alliance, while defending all of its members against any threat. NATO remains committed to fulfilling its three core tasks: collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security. At the Brussels Summit, the Alliance will make important decisions to further boost security in and around Europe, including through strengthened deterrence and defence, projecting stability and fighting terrorism, enhancing its partnership with the European Union, modernising the Alliance and achieving fairer burden-sharing. This Summit will be held in the new NATO Headquarters, a modern and sustainable home for a forward-looking Alliance. It will be the third meeting of Allied Heads of State and Government chaired by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. + Summit meetings + Member countries + Partners + NATO Secretary General Archived material – Information valid up to 10 July 2018 1 NATO Summit Guide, Brussels 2018 I. Strengthening deterrence and defence NATO’s primary purpose is to protect its almost one billion citizens and to preserve peace and freedom. NATO must also be vigilant against a wide range of new threats, be they in the form of computer code, disinformation or foreign fighters. The Alliance has taken important steps to strengthen its collective defence and deterrence, so that it can respond to threats from any direction. -

NATO Summit Guide Warsaw, 8-9 July 2016

NATO Summit Guide Warsaw, 8-9 July 2016 An essential Alliance in a more dangerous world The Warsaw Summit comes at a defining moment for the security of the North Atlantic Alliance. In recent years, the world has become more volatile and dangerous with Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and destabilisation of eastern Ukraine, as well as its military build-up from the Barents Sea to the Baltic, and from the Black Sea to the eastern Mediterranean; turmoil across the Middle East and North Africa, fuelling the biggest migrant and refugee crisis in Europe since World War Two; brutal attacks by ISIL and other terrorist groups, as well as cyber attacks, nuclear proliferation and ballistic missile threats. NATO is adapting to this changed security environment. It also remains committed to fulfilling its three core tasks: collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security. And, in the Polish capital, the Alliance will make important decisions to boost security in and around Europe, based on two key pillars: protecting its citizens through modern deterrence and defence, and projecting stability beyond its borders. NATO member states form a unique community of values, committed to the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law. In today’s dangerous world, transatlantic cooperation is needed more than ever. NATO embodies that cooperation, bringing to bear the strength and unity of North America and Europe. This Summit is the first to be hosted in Poland and the first to be chaired by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, who took up his post in October 2014. -

NATO's Military Committee

The International Military Staff (IMS) Six functional areas The IMS supports the Military Committee, with about The Military Committee oversees several of the IMS 400 dedicated military and civilian personnel working in operations and missions including the: an international capacity for the common interest of the Plans and Policy Alliance, rather than on behalf of their country of origin. ➤ International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan (ISAF). Responsible for strategic level plans Under the direction of the Director General, Lt.Gen. NATO is operating throughout Afghanistan with about 130,000 and policies, and defence/force Jürgen Bornemann, the staff prepare assessments, military personnel there under its command. ISAF has responsibility for, among other things, the provision of security, planning, including working with evaluations and reports on all issues that form the basis nations to determine national military Provincial Reconstruction Teams and training the Afghan of discussion and decisions in the MC. National Security Forces, known as the NATO Training Mission – NATO’s Military levels of ambition regarding force goals and contributions to NATO. Afghanistan (NTM-A). Supporting the transfer of responsibility The IMS is also responsible for planning, assessing for security to Afghan Authorities will remain a priority. Operations and recommending policy on military matters for ➤ Kosovo Force (KFOR). Since June 1999 NATO has led a Operation Active Endeavour is NATO’s Committee Closely tracks current operations, consideration by the Military Committee, and for peacekeeping operation in Kosovo. Initially composed of 50,000 maritime surveillance and escort operation staffs operational planning, follows ensuring their policies and decisions are implemented following the March 1999 air campaign, the force now numbers in the fight against terrorism. -

The EU's Maritime Security Strategy: a Neo-Medieval Perspective on The

CIRR XXII (75) 2016, 9-38 ISSN 1848-5782 UDC 656.6:347.79.061.1EU Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, DOI 10.1515/cirr-2016-0001 XXII (75) - 2016 The EU’s Maritime Security Strategy: a Neo-Medieval Perspective on the Limits of Soft Security? Brendan Flynn Abstract This paper offers a critical interpretation of the EU’s recent Maritime Security Strategy (MSS) of 2014, making distinctions between hard and soft conceptions of maritime security. The theoretical approach employed invokes the ‘EU as neo-medieval empire’ (Bull 1977: 254-255; Rennger 2006; Zielonka 2006). By this account, the main objectives of EU maritime strategy are stability and encouragement of globalised maritime trade flows to be achieved using the classic instruments of ‘soft maritime security’. While replete with great possibilities, the EU’s maritime security strategy is likely to be a relatively weak maritime security regime, which suffers from a number of important limits. KEY WORDS: European Union, maritime security strategy, hard and soft conceptions 9 Maritime Security – Hard and Soft Varieties? Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, XXII (75) - 2016 Since the declaration of its Marine Security Strategy (MSS) in 2014, the EU has loudly proclaimed itself to be a global player in maritime security. The subject of this paper is whether, in fact, it is likely to become a credible one. The exact question here is: What type of maritime security actor is the EU? Not: Why or how can we explain the emergence of the EU’s maritime security dimension? Those latter questions have already been well addressed by other scholars (Germond 2015; Riddervold 2011, 2015).