CRPT-105Erpt14.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nato Enlargement

Committee Reports POLITICAL SUB-COMMITTEE ON CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE REPORT NATO ENLARGEMENT Bert Koenders (Netherlands) International Secretariat Rapporteur October 2001 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: NATO ENLARGEMENT AND PRIORITIES FOR THE ALLIANCE II. NATO'S LAST ENLARGEMENT ROUND - LESSONS LEARNED A. CONTRIBUTION OF NEW MEMBERS TO EUROPEAN SECURITY B. THE MEMBERSHIP ACTION PLAN (MAP) III. STATUS OF PREPARATIONS OF THE NINE APPLICANT COUNTRIES A. ALBANIA B. BULGARIA C. ESTONIA D. LATVIA E. LITHUANIA F. THE FORMER YUGOSLAV REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA G. ROMANIA H. SLOVAKIA I. SLOVENIA IV. FURTHER NATO ENLARGEMENT AND SECURITY IN THE EURO- ATLANTIC AREA A. RELATIONS WITH RUSSIA B. RELATIONS WITH UKRAINE V. NATO ENLARGEMENT AND EU ENLARGEMENT VI. CONCLUSIONS VII. APPENDIX I. INTRODUCTION: NATO ENLARGEMENT AND PRIORITIES FOR THE ALLIANCE 1. The security landscape in Europe has been radically altered since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the "velvet revolutions" of 1989 and 1990. Though the risk of an all-out confrontation between the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact and NATO no longer exists, pockets of instability, including military conflict, remain on the European continent. The debate on NATO enlargement has to be seen principally in the context of the transformation of NATO from a defence alliance into an organisation additionally charged with providing, or at least contributing to, comprehensive security. 2. NATO's adaptation to the changing security environment is mirrored in its opening up to the countries in Central and Eastern Europe. This has been reflected in the updating of the Strategic Concept, but also in a process that consists of developing and intensifying dialogue and co-operation with the members of the former Warsaw Pact. -

Mikhail Gorbachev and the NATO Enlargement Debate: Then and Now 443

Mikhail Gorbachev and the NATO Enlargement Debate: Then and Now 443 Chapter 19 Mikhail Gorbachev and the NATO Enlargement Debate: Then and Now Pavel Palazhchenko The purpose of this chapter is to bring to the attention of research- ers materials relating to the antecedents of NATO enlargement that have not been widely cited in ongoing discussions. In the debate on NATO enlargement, both in Russia and in the West, the issue of the “assurances on non-enlargement of NATO” giv- en to Soviet leaders and specifically Mikhail Gorbachev in 1989-1990 has taken center stage since the mid-1990s. The matter is discussed not just by scholars, journalists and other non-policy-makers but also by major political figures, particularly in Russia, including President Vladimir Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. In the West, there has recently been renewed interest in the subject following the publi- cation of some declassified material by the National Security Archive, a Washington, D.C., non-profit organization with a somewhat mislead- ing name. While some of the aspects of the discussion of the “assurances” are similar in Russia and the West (conflation of fact and opinion, of bind- ing obligations and remarks relating to expectation or intent) the sub- text is different. In Russia most commentators accuse Gorbachev of being gullible and naïve and blithely accepting the assurances instead of demanding a binding legal guarantee of non-enlargement. In the West, the subtext is more often of the West’s bad faith in breaking what is supposed to be an informal “pledge of non-enlargement” given to Gor- bachev. -

7.1 Defense Spending During the Cold War (1947-1991)

Influencing NATO Shaping NATO Through U.S. Foreign Policy Justin Sing Masteroppgave Forsvarets høgskole Spring 2020 II *The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the position of the the United States Marine Corps, Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense. Summary An assessment of the influence of United States foreign policy impact on the decision of NATO members to formally accept policies which align with U.S. strategic goals. The assessment looks at the National Security Strategy and Defense Strategic documents of each United States Presidential Administration following the end of the Cold War to determine changes to U.S. commitment to NATO and the resultant changes to Alliance force posture and defense spending agreements. The paper also assesses the impacts of U.S. Administration changes in rhetoric, and of U.S. direct military action in specific NATO-led operations against the resultant decision of NATO members to accede to U.S. demands for increased defense spending. III *The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the position of the the United States Marine Corps, Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense. Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2 Method ............................................................................................................................ 3 3 United States Historical Perspective of the -

The Formation of Nato and Turkish Bids for Membership

AKADEMİK YAKLAŞIMLAR DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC APPROACHES KIŞ 2010 CİLT:1 SAYI:1 WINTER 2010 VOLUME:1 ISSUE:1 FROM NEUTRALITY TO ALIGNMENT: THE FORMATION OF NATO AND TURKISH BIDS FOR MEMBERSHIP Abdulkadir BAHARÇİÇEK* Abstract The formation of NATO was a responce by the United States to the security questions of the Western Europe and North Atlantic region. Turkey also faced with a serious threat from the Soviet Union. Turkey‟s attempts of entering NATO shaped Turkish security polices as well as her relations with the rest of the world. Turkish membership to NATO can be regarded a solution to her security problems, but it may well be argued that the main cause behind that policy was the continuation of the polices of westernization and modernization. The obvious short term factor behind Turkish desire was the Soviet threat. But at the same time the ideolojical aspirations in becoming an integral part- at least in term of military alliance- of Western world without any doubt played a decisive role in Turkey‟s decision. Özet İkinci Dünya Savaşı‟ndan sonra Avrupa‟da ortaya çıkan yeni güvenlik sorunları ve özellikle Batı Avrupa‟ya da yönelen Sovyet tehdidine karşı ABD‟nin öncülüğünde NATO ittifakı kuruldu. Aynı dönemde Türkiye‟de kendisini Sovyet tehdidi altında görüyordu. Türkiye‟nin NATO‟ya girme çabaları Türkiye‟nin güvenlik politikalarını ve Batı ile olan ilişkilerini de şekillendirdi. NATO üyeliği, Türkiye açısından, güvenlik sorunlarına bir çözüm olarak görülebilir, fakat bu üye olma arzusunun arkasında modernleşme ve batılılaşma ideolojisinin bulunduğunu söylemek de yanlış olmayacaktır. Kısa dönemde Sovyet tehdidine karşı koymanın hesapları yapılırken, uzun vadede Batı sisteminin ayrılmaz bir parçası olma arzusunun Türk karar alıcılarının temel düşüncesi olduğu söylenebilir. -

NATO Expansion: Benefits and Consequences

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 NATO expansion: Benefits and consequences Jeffrey William Christiansen The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Christiansen, Jeffrey William, "NATO expansion: Benefits and consequences" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8802. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8802 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■rr - Maween and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of M ontana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission X No, I do not grant permission ________ Author's Signature; Date:__ ^ ^ 0 / Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. MSThe»i9\M«r«f»eld Library Permission Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NATO EXPANSION: BENEFITS AND CONSEQUENCES by Jeffrey William Christiansen B.A. University of Montana, 2000 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2001 Approved by: hairpers Dean, Graduate School 7 - 24- 0 ^ Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Remarks at the Opening of the North Atlantic Council Meeting on Kosovo April 23, 1999

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1999 / Apr. 23 that is doing so much to reduce crime on our By taking actions to prevent future acts of streets to our schools. Today I’m pleased to violence in our schools, we can best honor the announce the first of the grants funding these memories of those who lost their lives. community police will be awarded to 336 Thank you very much. schools and communities to help hire more than 600 police officers. Like their counterparts on Legislative Initiatives/Kosovo the streets, these school officers will work close- Q. Mr. President, you didn’t mention gun ly with the citizens they serve, with students, control. Are you going to do more on gun con- teachers, and parents, to improve campus secu- trol? rity, to counsel troubled youth, to mediate con- Q. To be clear, sir, do all hostilities in Kosovo flicts before they escalate into violence. have to end before there can be consideration I want to thank Senator Chuck Robb for his of ground troops, sir? strong leadership on this issue. By the end of The President. First of all, I know you under- the year we hope to have 2,000 new officers stand I’ve got to run over there and meet all in our schools, and I encourage all communities the people who are coming. We will have more to apply for these grants. legislative initiatives to announce in the days I also want to take this opportunity to remind ahead. As I said a couple of days ago, we will communities that they have until June 1st to have some legislative responses and efforts we apply for the Federal Safe Schools-Healthy Stu- have been working on for some time, actually. -

The Nato-Russia Council and Changes in Russia's Policy

THE NATO-RUSSIA COUNCIL AND CHANGES IN RUSSIA’S POLICY TOWARDS NATO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY BEISHENBEK TOKTOGULOV IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS SEPTEMBER 2015 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık (METU,IR) Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever (METU,IR) Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU,IR) Prof. Dr. Fırat Purtaş (GU,IR) Assist. Prof. Dr. Taylan Özgür Kaya (NEU,IR) ii PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Beishenbek Toktogulov Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE NATO-RUSSIA COUNCIL AND CHANGES IN RUSSIA’S POLICY TOWARDS NATO Toktogulov, Beishenbek Ph.D., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever September 2015, 298 pages The objective of this thesis is to explain the changes in Russia’s policy towards NATO after the creation of the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) in 2002. -

International Military Staff, Is to Provide the Best Possible C3 Staff Executive Operations, Strategic Military Advice and Staff Support for the Military Committee

Director General of IMS Public Affairs & Financial Controller StratCom Executive Coordinator Advisor Legal Office HR Office NATO Office Support Activities on Gender Perspectives SITCEN Cooperation NATO Intelligence Operations Plans & Policy & Regional Logistics Headquarters Security & Resources C3 Staff Intelligence Major Operation Strategic Policy Partnership Concepts Logistics Branch Executive Production Branch Alpha & Concepts & Policy Branch Coordination Office Branch Intelligence Policy Joint Operations Nuclear Special Partnerships Medical Branch Information Services Branch & Plans Branch & CBRN Defence Branch Branch Education Training Defence and Regional Partnerships Plans, Policy & Exercise & Evaluation Force Planning Armaments Branch Branch Branch Architecture Branch Air & Missile Infrastructure & Spectrum & C3 Defence Branch Finance Branch Infrastructure Branch Operations, Manpower Branch Requirements, & Plans Branch NATO Defence Information Assurance Consists of military/civilian staff from member nations. Manpower & Cyber Defence Personnel work in international capacity for the common interest of the Alliance. Audit Authority Branch www.nato.int/ims e-mail :[email protected] Brussels–Belgium 1110 HQ, NATO Office,InternationalMilitaryStaff, Affairs the Public For moreinformationcontact: NATO HQ. NATO and the moveto thenew NATO are adaptedtoreflect Future ‘ways ofworking’ changes are not it likely, will be important that the IMS is reconfigured and its a review of the IMS Summit, Chicago the was at direction initiated. Government and State While of Heads major the Following structural and organizational respected andthatistotallyfreefromdiscriminationprejudice. is individual each which in environment an in communication open and initiative resilience, for need the and learning continuous promote also They commitment. first, Mission always.’ Our peopleThe workIMS with professionalism,team integrityembraces and the principles and values enshrined Values in ‘People decisiveness andpride. -

NATO 20/2020: Twenty Bold Ideas to Reimagine the Alliance After The

NATO 2O / 2O2O TWENTY BOLD IDEAS TO REIMAGINE THE ALLIANCE AFTER THE 2020 US ELECTION NATO 2O/2O2O The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. The Scowcroft Center’s Transatlantic Security Initiative brings together top policymakers, government and military officials, business leaders, and experts from Europe and North America to share insights, strengthen cooperation, and develop innovative approaches to the key challenges facing NATO and the transatlantic community. This publication was produced in partnership with NATO’s Public Diplomacy Division under the auspices of a project focused on revitalizing public support for the Alliance. NATO 2O / 2O2O TWENTY BOLD IDEAS TO REIMAGINE THE ALLIANCE AFTER THE 2020 US ELECTION Editor-in-Chief Christopher Skaluba Project and Editorial Director Conor Rodihan Research and Editorial Support Gabriela R. A. Doyle NATO 2O/2O2O Table of Contents 02 Foreword 56 Design a Digital Marshall Plan by Christopher Skaluba by The Hon. Ruben Gallego and The Hon. Vicky Hartzler 03 Modernize the Kit and the Message by H.E. Dame Karen Pierce DCMG 60 Build Resilience for an Era of Shocks 08 Build an Atlantic Pacific by Jim Townsend and Anca Agachi Partnership by James Hildebrand, Harry W.S. Lee, 66 Ramp Up on Russia Fumika Mizuno, Miyeon Oh, and by Amb. -

NATO Enlargement: Poland, the Baltics, Ukraine and Georgia

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2018 NATO Enlargement: Poland, The Baltics, Ukraine and Georgia Christopher M. Radcliffe University of Central Florida Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Radcliffe, Christopher M., "NATO Enlargement: Poland, The Baltics, Ukraine and Georgia" (2018). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 400. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/400 NATO ENLARGEMENT: POLAND, THE BALTICS, UKRAINE AND GEORGIA By CHRISTOPHER M. RADCLIFFE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in International and Global Studies in the College of Sciences and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2018 Thesis Chair: Houman Sadri, Ph.D. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is the most difficult project that I’ve ever taken on. At this time, I’d like to thank a number of people that helped me through this process. I’ve had the pleasure of working with two brilliant professors – Dr. Houman Sadri, who is my thesis chair and Dr. Vladimir Solonari, a member of my thesis committee. Thank you for all of the motivation over the past year and time you both have taken to assist me with completing this project. -

Dod Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9

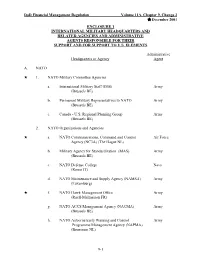

DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9, Change 2 December 2001 ENCLOSURE 1 INTERNATIONAL MILITARY HEADQUARTERS AND RELATED AGENCIES AND ADMINISTRATIVE AGENTS RESPONSIBLE FOR THEIR SUPPORT AND FOR SUPPORT TO U.S. ELEMENTS Administrative Headquarters or Agency Agent A. NATO 1. NATO Military Committee Agencies a. International Military Staff (IMS) Army (Brussels BE) b. Permanent Military Representatives to NATO Army (Brussels BE) c. Canada - U.S. Regional Planning Group Army (Brussels BE) 2. NATO Organizations and Agencies a. NATO Communications, Command and Control Air Force Agency (NC3A) (The Hague NL) b. Military Agency for Standardization (MAS) Army (Brussels BE) c. NATO Defense College Navy (Rome IT) d. NATO Maintenance and Supply Agency (NAMSA) Army (Luxemburg) f. NATO Hawk Management Office Army (Ruell-Malmaison FR) g. NATO ACCS Management Agency (NACMA) Army (Brussels BE) h. NATO Airborne Early Warning and Control Army Programme Management Agency (NAPMA) (Brunssum NL) 9-1 DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9, Change 2 December 2001 Administrative Headquarters or Agency Agent i. NATO Airborne Early Warning Force Command Army (Mons BE) j. NATO Airborne Early Warning Main Operating Base Air Force (Geilenkirchen GE) k. NATO CE-3A Component Air Force (Geilenkirchen GE) l. NATO Research and Technology Organization (RTO) Air Force (Nueilly-sur-Seine FR) l. NATO School Army (Oberammergau GE) m. NATO CIS Operating and Support Agency (NACOSA) Army (Glons BE) n. NATO Communication and Information Systems School Navy (NCISS) (Latina, IT) o. NATO Pipeline Committee (NPC) Army (Glons BE) p. NATO Regional Operating Center Atlantic Navy (ROCLANT)/NACOSA Support Element (NSE) West (Oeiras PO) 3. -

The Prague Summit and Nato's Transformation

THE PRAGUE SUMMIT AND NATO’S TRANSFORMATION NATO PUBLIC DIPLOMACY DIVISION 1110 Brussels - Belgium Web site: www.nato.int E-mail: [email protected] A READER’S GUIDE THE PRAGUE SUMMIT AND NATO’S TRANSFORMATION SUMMIT AND NATO’S THE PRAGUE PRARGENG0403 A READER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 I THE SUMMIT DECISIONS 9 II KEY ISSUES 19 New members: Expanding the zone of security 20 New capabilities: Adapting to modern challenges 26 New relationships: Practical cooperation and dialogue 34 After Prague: The road ahead 67 © NATO 2003 NATO INVITEES Country* Capital Population GDP Defence Active Troop *Data based on (million) (billion expenditures Strength national sources Euros) (million Euros) Bulgaria (25) Sofia 7.8 16.9 494 (2.9% GDP) 52 630 Estonia (27) Tallin 1.4 6.8 130 (1.9% GDP) 4 783 Latvia (33) Riga 2.3 8.8 156 (1.8% GDP) 9 526 Lithuania (34) Vilnius 3.5 14.5 290 (2.0% GDP) 17 474 Romania (36) Bucharest 22.3 47.9 1117 (2.3% GDP) 99 674 Slovakia (38) Bratislava 5.4 24.9 493 (2.0% GDP) 29 071 ★ Slovenia (39) Ljubljana 2.0 22.4 344 (1.5% GDP) 7 927 III DOCUMENTATION 71 Prague Summit Declaration – 21 November 2002 72 Prague Summit Statement on Iraq – 21 November 2002 78 Announcement on Enlargement – 21 November 2002 79 Report on the Comprehensive Review of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council and Partnership for Peace - 21 November 2002 80 Partnership Action Plan Against Terrorism - 21 November 2002 87 Chairman’s Summary of the Meeting of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council at Summit Level – 22 November 2002 94 Statement by NATO