Review of SNV's Pro-‐Poor Support Mechanism in Banteay Meas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prakas on the Establishment of Secretariat of Kampot Provincial

The Khmer version is the official version of this document. Document prepared by the MLMUPC Cambodia, supported by ADB TA 3577 and LMAP TA GTZ. Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction No. 086 Prakas/ August 01, 2002 Prakas on The Establishment of Secretariat of Kamot Provincial Cadastral Commission and Composition of Districts Cadastral Commission in the Kampot province - Referring to the Constitution Kingdom of Cambodia - Referring to Preah Reach Kret No NS/RKT/1189/72 of November 30, 1998 on the Appointment of Royal Govemment of Cambodia, - Referring to Preah Reach Kram No 02/NS/94 of July 20, 1994 promulgating the law on the Organization and Functioning of the Council of Ministers; - Referring to Preah Reach Kram No NS/RKM/0699/09 of June 23, 1999 promulgating the Law on the Establishment of the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction, - Referring to Preah Reach Kram No NS/RKM/0801/14 of August 30, 2001 promulgating the Land Law, - Referring to Sub-Decree No 47 ANK/BK of May 31, 2002 on the Organization and Functioning of the Cadastral Commission, - Referring to Sub-Decree No 347 ANK/BK of July 17, 2002 on Nomination of Composition of the National Cadastral Commission; - Referring to Joint Prakas No 077 PK. of July 16, 2002 on Nomination of Composition of the Provincial/Municipal Cadastral Commission; - Pursuant to the proposal of Kampot Cadastral Commission Decision Praka 1: The Secretariat of Kampot Provincial Cadastral Commission should have been established in which it was composed of the following members: - Mr. Yin Vuth, chief of the office LMUPC and Geog. -

A Field Trip's Report in Veal Veng District, Pursat

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa DC-Cam’s Promoting Accountability Project A Field Trip’s Report in Veal Veng District, Pursat Province May 18-24, 2011 By Long Dany General Description and Brief History of Districts After the integration of the Khmer Rouge forces by the Cambodian government in 1996, Veal Veng was created as a district in Pursat province. Previously, Veal Veng had been one of the communes included within the Kravanh district. Veal Veng is approximately 120 kilometers from Pursat, and it can be reached by Road Number 56 which links Pursat and Veal Veng across the Kavanh district. The road between Pursat and Kravanh district is paved and smooth, but the road from the Kravanh district to Veal Veng is bumpy and rough. It is a gravel paved road with several old and ailing bridges. The Veal Veng district town is located 75 kilometers from the Thai border of the Trat province. The border checkpoint is called Thma Da. Nowadays, the authorities of both countries allow their citizens to cross the border only on Saturdays. Approximately 60 kilometers south of the Veal Veng district is the O Ta Som commune, where a Chinese company is building a hydroelectric power station. O Ta Som is just about 40 kilometers from the Koh Kong provincial town. Veal Veng comprises of five communes: Pramoy, Anlong Reap, O Ta Som, Kra Peu Pi, and Thma Da. Veal Veng has a population of 13,822 people—3,197 families. At the present time, the government is drafting a decree to create more communes and villages for Veal Veng because of its huge space of land. -

I Came to Beg in the City Because

I come to beg in the city because... A study on women begging in Phnom Penh Womyn’s Agenda for Change I come to beg in the city because … March, 2002 Phnom Penh-Cambodia Womyn’s Agenda for Change Cambodia-2002 0 I come to beg in the city because... A study on women begging in Phnom Penh TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................1 FORWARD.................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................................................ 4 ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................. 4 PART ONE: RESEARCH DESCRIPTION ............................................................................... 5 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 2. OBJECTIVE OF THE RESEARCH ................................................................................................ 6 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 6 4. PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED DURING THE RESEARCH ............................................................... 6 5. RESEARCH LOCATION ............................................................................................................ -

Cambodia PRASAC Microfinance Institution

Maybank Money Express (MME) Agent - Cambodia PRASAC Microfinance Institution Branch Location Last Update: 02/02/2015 NO NAME OF AGENT REGION / PROVINCE ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER OPERATING HOUR 1 PSC Head Office PHNOM PENH #25, Str 294&57, Boeung Kengkang1,Chamkarmon, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 023 220 102/213 642 7.30am-4pm National Road No.5, Group No.5, Phum Ou Ambel, Krong Serey Sophorn, Banteay 2 PSC BANTEAY MEANCHEY BANTEAY MEANCHEY Meanchey Province 054 6966 668 7.30am-4pm 3 PSC POAY PET BANTEAY MEANCHEY Phum Kilometre lek 4, Sangkat Poipet, Krong Poipet, Banteay Meanchey 054 63 00 089 7.30am-4pm Chop, Chop Vari, Preah Net 4 PSC PREAH NETR PREAH BANTEAY MEANCHEY Preah, Banteay Meanchey 054 65 35 168 7.30am-4pm Kumru, Kumru, Thmor Puok, 5 PSC THMAR POURK BANTEAY MEANCHEY Banteay Meanchey 054 63 00 090 7.30am-4pm No.155, National Road No.5, Phum Ou Khcheay, Sangkat Praek Preah Sdach, Krong 6 PSC BATTAMBANG BATTAMBANG Battambang, Battambang Province 053 6985 985 7.30am-4pm Kansai Banteay village, Maung commune, Moung Russei district, Battambang 7 PSC MOUNG RUESSEI BATTAMBANG province 053 6669 669 7.30am-4pm 8 PSC BAVEL BATTAMBANG Spean Kandoal, Bavel, Bavel, BB 053 6364 087 7.30am-4pm Phnom Touch, Pech Chenda, 9 PSC PHNOM PROEK BATTAMBANG Phnum Proek, BB 053 666 88 44 7.30am-4pm Boeng Chaeng, Snoeng, Banan, 10 PSC BANANN BATTAMBANG Battambang 053 666 88 33 7.30am-4pm No.167, National Road No.7 Chas, Group No.10 , Phum Prampi, Sangkat Kampong 11 PSC KAMPONG CHAM KAMPONG CHAM Cham, Krong Kampong Cham, Kampong Cham Province 042 6333 000 7.30am-4pm -

Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia

ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2013 EDITION Compiled by Electricity Authority of Cambodia from Data for the Year 2012 received from Licensees Electricity Authority of Cambodia ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2013 EDITION Compiled by Electricity Authority of Cambodia from Data for the Year 2012 received from Licensees Report on Power Sector for the Year 2012 0 Electricity Authority of Cambodia Preface The Annual Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2013 Edition is compiled from informations for the year 2012 availble with EAC and received from licensees, MIME and other organizations in the power sector. The data received from some licensees may not up to the required level of accuracy and hence the information provided in this report may be taken as indicative. This report is for dissemination to the Royal Government, institutions, investors and public desirous to know about the situation of the power sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia during the year 2012. With addition of more HV transmission system and MV sub-transmission system, more and more licensees are getting connected to the grid supply. This has resulted in improvement in the quality of supply to more consumers. By end of 2012, more than 91% of the consumers are connected to the grid system. More licensees are now supplying electricity for 24 hours a day. The grid supply has reduced the cost of supply and consequently the tariff for supply to consumers. Due to lower cost and other measures taken by Royal Government of Cambodia, in 2012 there has been a substantial increase in the number of consumers availing electricity supply. -

List of Interviewees

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA Phnom Penh, Cambodia LIST OF POTENTIAL INFORMANTS FROM MAPPING PROJECT 1995-2003 Banteay Meanchey: No. Name of informant Sex Age Address Year 1 Nut Vinh nut vij Male 61 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 2 Ol Vus Gul vus Male 40 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 3 Um Phorn G‘¿u Pn Male 50 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 4 Tol Phorn tul Pn ? 53 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 5 Khuon Say XYn say Male 58 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 6 Sroep Thlang Rswb føag Male 60 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 7 Kung Loeu Kg; elO Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 8 Chhum Ruom QuM rYm Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 9 Than fn Female ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for the Truth EsVgrkKrBit edIm, IK rcg©M nig yutþiFm‘’ DC-Cam 66 Preah Sihanouk Blvd. P.O.Box 1110 Phnom Penh Cambodia Tel: (855-23) 211-875 Fax: (855-23) 210-358 [email protected] www.dccam.org 10 Tann Minh tan; mij Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 11 Tatt Chhoeum tat; eQOm Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 12 Tum Soeun TMu esOn Male 45 Banteay Meanchey province, Preah Net Preah district 1997 13 Thlang Thong føag fug Male 49 Banteay Meanchey province, Preah Net Preah district 1997 14 San Mean san man Male 68 Banteay Meanchey province, -

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002/02 ■ Issue 65 ■ Hearings on Evidence Week 62 ■ 29 Aug - 1 Sept 2016

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002/02 ■ Issue 65 ■ Hearings on Evidence Week 62 ■ 29 Aug - 1 Sept 2016 Case of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan A project of East-West Center and the WSD HANDA Center for Human Rights and International Justice at Stanford University (previously known as the UC Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center) “It was very difficult situation during the regime… If we were forced or instructed to get married, we simply did.” - Civil Party Seng Soeun I. OVERVIEW This week the Trial Chamber continued to hear testimony related to the regulation of marriage during Democratic Kampuchea (DK). The Chamber first heard from Civil Party Mr. Seng Soeun, who arranged group wedding ceremonies for handicapped soldiers with women from Kampot pepper plantations. On Tuesday afternoon, Civil Party Ms. Chea Dieb testified about a policy, announced by Khieu Samphan at a meeting she attended in Phnom Penh, that everyone over the age of 19 working at a ministry should be married. Finally, Witness Ms. Phan Him, a former member of the Ministry of Commerce, testified about her own experience of marriage while based near Tuol Tom Pong Market, as well as her knowledge of arrests of people connected to the North Zone. At the end of the week the Trial Chamber held a lengthy debate on the appearance of a demographic expert 2-TCE-93, who was originally proposed by both the OCP and Nuon Chea Defense Team. II. SUMMARY OF WITNESS AND CIVIL PARTY TESTIMONY The Chamber heard from Civil Parties Seng Soeun and Chea Dieb, and Witness Phan Van this week, all on the regulation of marriage. -

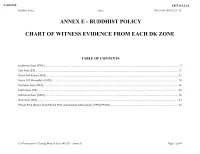

Buddhist Policy Chart of Witness Evidence from Each

ERN>01462446</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC ANNEX E BUDDHIST POLICY CHART OF WITNESS EVIDENCE FROM EACH DK ZONE TABLE OF CONTENTS Southwest Zone [SWZ] 2 East Zone [EZ] 12 Sector 505 Kratie [505S] 21 Sector 105 Mondulkiri [105S] 24 Northeast Zone [NEZ] 26 North Zone [NZ] 28 Northwest Zone [NWZ] 36 West Zone [WZ] 43 Phnom Penh Special Zone Phnom Penh Autonomous Municipality [PPSZ PPAM] 45 ’ Co Prosecutors Closing Brief in Case 002 02 Annex E Page 1 of 49 ERN>01462447</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC SOUTHWEST ZONE [SWZ] Southwest Zone No Name Quote Source Sector 25 Koh Thom District Chheu Khmau Pagoda “But as in the case of my family El 170 1 Pin Pin because we were — we had a lot of family members then we were asked to live in a monk Yathay T 7 Feb 1 ” Yathay residence which was pretty large in that pagoda 2013 10 59 34 11 01 21 Sector 25 Kien Svay District Kandal Province “In the Pol Pot s time there were no sermon El 463 1 Sou preached by monks and there were no wedding procession We were given with the black Sotheavy T 24 Sou ” 2 clothing black rubber sandals and scarves and we were forced Aug 2016 Sotheavy 13 43 45 13 44 35 Sector 25 Koh Thom District Preaek Ph ’av Pagoda “I reached Preaek Ph av and I saw a lot El 197 1 Sou of dead bodies including the corpses of the monks I spent overnight with these corpses A lot Sotheavy T 27 of people were sick Some got wounded they cried in pain I was terrified ”—“I was too May 2013 scared to continue walking when seeing these -

Chapter 4: Development Strategy for Kampot

The Study on National Integrated Strategy of Coastal Area and Master Plan of Sihanouk-ville for Sustainable Development Final Report (Book II) CHAPTER 4: DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FOR KAMPOT 4.1 Issues in the Present Conditions of Kampot 4.1.1 Socio Economic Condition According to the 2008 Census, the total population in the Kampot province was 585,850, of which only 8.2% of population was living in urban area. Population density of the province was 120/km2, which was considerably higher than the national average of 56/km2. In Kampot, 36.4% of the population (225,039) was under 15 years of age. Working age population (age between 15 and 64) was 377,315 or 61.0% of the population. Labor force participation rate1 of Kampot (81.5%) in 2008 was higher than that of the national average (76.9%) and the Study area average (76.4%). About 85% of labor force in the province was engaged in agriculture. The high labor force participation rate in Kampot is considered to be a result from extensive self-employed agricultural activities. The economically active segment of the population (employed population + unemployed population) was 309,098, which accounted for 49.9% of the total population in the province. Population of the Kampot province has increased by 1.0% per annum between 1998 and 2008. During the same period, the number of labor force in the Study area has increased more rapidly from 230,411 to 309,093 with annual average increase rate of 3.0%. Table 4.1.1 Change in Population and Number of Labor Force in Kampot Province Population Labor Force Urban Rural Total 1998 Census 45,240 483,165 528,405 230,411 2008 Census 48,274 537,576 585,850 309,093 Annual Growth Rate (98-08) 0.7% 1.1% 1.0% 3.0% Source: CENSUS 1998 and 2008, NIS Such a rapid increase in labor force was attributed to 4 main factors; namely 1) increase in the total population, 2) increase in the percentage of working age population to total population (51.6% -> 61.0%), 3) increase in the labor force participation rate (75.4% -> 81.5%), and 4) decrease in the crude unemployment rate (3.7% -> 1.4%). -

The Master Plan Study on Rural Electrification by Renewable Energy in the Kingdom of Cambodia

No. Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy in the Kingdom of Cambodia THE MASTER PLAN STUDY ON RURAL ELECTRIFICATION BY RENEWABLE ENERGY IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME 5: APPENDICES June 2006 Japan International Cooperation Agency NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD., Tokyo ED JR KRI INTERNATIONAL CORP., Tokyo 06-082 Japan International Ministry of Industry, Mines and Cooperation Agency Energy in the Kingdom of Cambodia THE MASTER PLAN STUDY ON RURAL ELECTRIFICATION BY RENEWABLE ENERGY IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME 5 : APPENDICES June 2006 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD., Tokyo KRI INTERNATIONAL CORP., Tokyo Final Report (Appendices) Abbreviations Abbreviations Abbreviation Description ADB Asian Development Bank Ah Ampere hour ASEAN Association of South East Asian Nations ATP Ability to Pay BCS Battery Charging Station CBO Community Based Organization CDC Council of Development for Cambodia CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEC Community Electricities Cambodia CF Community Forestry CFR Complementary Function to REF CIDA Canadian International Development Agency DAC Development Assistance Committee DIME Department of Industry, Mines and Energy DNA Designated National Authority EAC Electricity Authority of Cambodia EdC Electricite du Cambodge EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return ESA Energy Service Agent ESCO Energy Service Company EU European Union FIRR Financial Internal Rate of Return FS Feasibility Study GDP Gross Domestic Product GEF Global Environment Facility GHG Greenhouse Gas GIS Geographic -

Planned Celebrations for International Human Rights Day 2012

Planned Celebrations for International Human Rights Day 2012 No Province Profile Organizer Planned Event 1 Banteay Meanchey Cambodia Tourism and Polinha Public forum on 9th December on human rights issues. (Around 100 people) Service Workers’ 092 557 235 Federation (CTSWF) 2 Banteay Meanchey Independent Democracy of Manith Kong Public forum on 9th December on human rights issues, including briefing statements from Informal Economy 089 397 074 motodop representatives and migrant workers, a march to Banteay Meanchey municipality Association (IDEA), Kbal & submission of a petition. (Around 350 people) Spean 1, Poi Pet district 3 Banteay Meanchey Chankiri village, Poi Pet Chiev Sam Ath Public forum on 9-10th December at Aphiwad primary school on human rights issues, commune, O Chrov district 078 229 521 including a religious ceremony and Q&A session. From 6.30 am to 5.00 pm. (Around 350 people) 4 Banteay Meanchey Pkham village, Pkham Chan Saron Public forum on 10th December at Thmar Puk and Svay Chet federation office on economic commune, Svay Chet & 017 981 800 and cultural rights, including a Q&A session & balloon release. From 8.30 am to 11.30 am. Thmar Puk district 097 638 8257 (Around 450 people, including students and teachers) 5 Banteay Meanchey Santepheap village, Toul Nou Leng Public forum on 10th December on human rights issues and land issues, including a Q&A Pongror commune, Malay 017 331 907 session. From 7.00 am to 9.30 am. (Around 400 people) district 088 913 0519 6 Banteay Meanchey The Cambodian League for Nget Sokun Visits to 18 prisons in Phnom Penh and across Cambodia (PJ, CC1, CC2 in Phnom Penh the Promotion and Defense 016 797 305 and 13 provincial prisons) on 10th December including longer visist with 13 human rights of Human Rights Naly Pilorge defenders (HRDs) in Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Kampong Chhnang, Kampong (LICADHO) 012 803 650 Thom, Oddur Meanchey, Pailin and Phnom Penh prisons. -

Title Kampot of the Belle Epoque: from the Outlet of Cambodia to A

Kampot of the Belle Epoque: From the Outlet of Cambodia to a Title Colonial Resort(<Special Issue>New Japanese Scholarship in Cambodian Studies) Author(s) Kitagawa, Takako Citation 東南アジア研究 (2005), 42(4): 394-417 Issue Date 2005-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/53808 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4, 東南アジア研究 March 2005 42巻 4 号 Kampot of the Belle Époque: From the Outlet of Cambodia to a Colonial Resort KITAGAWA Takako* Abstract Historical studies about Cambodia have paid little attention to regional factors, and historians have been hardly able to give much perspective about the history of particular regions within the country. Therefore, this paper looks at Kampot as it was during the French colonial period in order to understand the foundations of present-day Kampot. Presently, Kampot is the name of a province and its capital city, which face the Gulf of Thailand. During the colonial period, it was an administrative center for the circonscription résidentielle that extended over the coastal region. The principal sources for this paper are the “Rapports périodiques, économiques et politiques de la résidence de Kampot,” from 1885 to 1929, collected in the Centre des Archives d’Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence, France. Drawing from the results of our examination, we can recognize two stages in the history of Kampot. These are (1) the Kampot of King Ang-Duong, and (2) modern Kampot, which was con- structed by French colonialism. King Ang-Duong’s Kampot was the primary sea outlet for his landlocked kingdom.