Southern Africa, Vol. 12, No. 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

Author Accepted Manuscript

University of Dundee Campaigning against apartheid Graham, Matthew Published in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2018.1506871 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Graham, M. (2018). Campaigning against apartheid: The rise, fall and legacies of the South Africa United Front 1960-1962. Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 46(6), 1148-1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2018.1506871 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Campaigning against apartheid: The rise, fall and legacies of the South Africa United Front 1960- 1962 Matthew Graham University of Dundee Research Associate at the International Studies Group, University of the Free State, South Africa Correspondence: School of Humanities, University of Dundee, Nethergate, Dundee, DD1 4HN. [email protected] 01382 388628 Acknowledgements I’d like to thank the anonymous peer-reviewers for offering helpful and constructive comments and guidance on this article. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Year of Fire, Year of Ash. the Soweto Revolt: Roots of a Revolution?

Year of fire, year of ash. The Soweto revolt: roots of a revolution? http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ESRSA00029 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Year of fire, year of ash. The Soweto revolt: roots of a revolution? Author/Creator Hirson, Baruch Publisher Zed Books, Ltd. (London) Date 1979 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1799-1977 Source Enuga S. Reddy Rights By kind permission of the Estate of Baruch Hirson and Zed Books Ltd. Description Table of Contents: -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project STEVE McDONALD Interviewed by: Dan Whitman Initial Interview Date: August 17, 2011 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Education MA, South African Policy Studies, University of London 1975 Joined Foreign Service 1975 Washington, DC 1975 Desk Officer for Portuguese African Colonies Pretoria, South Africa 1976-1979 Political Officer -- Black Affairs Retired from the Foreign Service 1980 Professor at Drury College in Missouri 1980-1982 Consultant, Ford Foundation’s Study 1980-1982 “South Africa: Time Running Out” Head of U.S. South Africa Leadership Exchange Program 1982-1987 Managed South Africa Policy Forum at the Aspen Institute 1987-1992 Worked for African American Institute 1992-2002 Consultant for the Wilson Center 2002-2008 Consulting Director at Wilson Center 2009-2013 INTERVIEW Q: Here we go. This is Dan Whitman interviewing Steve McDonald at the Wilson Center in downtown Washington. It is August 17. Steve McDonald, you are about to correct me the head of the Africa section… McDONALD: Well the head of the Africa program and the project on leadership and building state capacity at the Woodrow Wilson international center for scholars. 1 Q: That is easy for you to say. Thank you for getting that on the record, and it will be in the transcript. In the Wilson Center many would say the prime research center on the East Coast. McDONALD: I think it is true. It is a think tank a research and academic body that has approximately 150 fellows annually from all over the world looking at policy issues. -

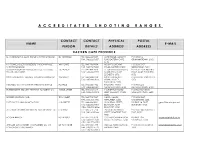

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Washington Notes on Africa

AUTUMN, 1982 WASHINGTON NOTES ON AFRICA Scholarships: Education or Indoctrination? The Reagan Admini- promoted by Assistant stration is once again Secretary Chester Crock moving to thwart South A Decade of Struggle: 1972-1982 er as a complement to Africa's liberation strug scholarship opportun gle. Over the past year, We are proud to present this special anniversary edition to you. ities. Crocker has con the White House and For ten years, the Washington Notes on Africa has kept you demned solely "exter Congress have ad informed about events in Southern Africa and US policy responses. nal" programs which vanced characteris We take pride in knowing that this publication has played an bring South African tically different ap important role in the struggle for the liberation of Southern Africa. students and refugees proaches to the educa As in this issue, we have exposed US complicity with white minority to the US because they tional needs of Black regimes and have probed South Africa's efforts to gain support for "benefit the top achiev South Africans. Con its racist apartheid system in this country. In our endeavor to make ers within apartheid gress, rather than in each issue informative and readable, we have sought to provide you education, while writ creasing funding for with the informational resources to educate, to motivate, and to ing off apartheid's sad refugee education, has agitate for an end to the unjust racist system and US support for it. dest victims." initiated a new scholar You, our readers, have given us the political, moral, and financial Actually, the Reagan ship program to permit support to keep us going through the good and lean times. -

Title: Black Consciousness in South Africa : the Dialectics of Ideological

Black Consciousness in South Africa : The Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White title: Supremacy SUNY Series in African Politics and Society author: Fatton, Robert. publisher: State University of New York Press isbn10 | asin: 088706129X print isbn13: 9780887061295 ebook isbn13: 9780585056890 language: English Blacks--South Africa--Politics and government, Blacks--Race identity--South Africa, South Africa-- Politics and government--1961-1978, South subject Africa--Politics and government--1978- , South Africa--Social conditions--1961- , Blacks--South Africa--Social cond publication date: 1986 lcc: DT763.6.F37 1986eb ddc: 305.8/00968 Blacks--South Africa--Politics and government, Blacks--Race identity--South Africa, South Africa-- Politics and government--1961-1978, South subject: Africa--Politics and government--1978- , South Africa--Social conditions--1961- , Blacks--South Africa--Social cond Page i Black Consciousness in South Africa Page ii SUNY Series in African Politics and Society Henry L. Bretton and James Turner, Editors Page iii Black Consciousness in South Africa The Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White Supremacy Robert Fatton Jr. State University of New York Press Page iv Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1986 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, N.Y., 12246 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Fatton, Robert. Black consciousness in South Africa. (SUNY series in African politics and society) Revision of the author's thesis (Ph.D)University of Notre Dame. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

On the Edge of Capitalism: African Local States, Chinese Family Firms, and the Transformation of Industrial Labor

On the Edge of Capitalism: African Local States, Chinese Family Firms, and the Transformation of Industrial Labor The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987929 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA On the Edge of Capitalism: African Local States, Chinese Family Firms, and the Transformation of Industrial Labor A dissertation presented By Liang Xu to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Liang Xu All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Caroline Elkins Liang Xu On the Edge of Capitalism: African Local States, Chinese Family Firms, and the Transformation of Industrial Labor ABSTRACT This research, a study of capitalism on the frontier, examines Chinese garment production and African women workers in South Africa from the waning years of apartheid to the present. It focuses on Newcastle, a former border town between white South Africa and the black KwaZulu homeland that had been economically important for its coal and steel production since the 1960s. However, the “Asian Strategy” adopted by the Newcastle Town Council in the early 1980s transformed the town into a prominent site of low-wage, labor-intensive, and female-oriented light manufacturing. -

Contextual Theology and Its Radicalization of the South African Anti-Apartheid Church Struggle

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Confrontational Christianity: Contextual Theology and Its Radicalization of the South African Anti-Apartheid Church Struggle Miguel Rodriguez University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rodriguez, Miguel, "Confrontational Christianity: Contextual Theology and Its Radicalization of the South African Anti-Apartheid Church Struggle" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4470. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4470 CONFRONTATIONAL CHRISTIANITY: CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGY AND ITS RADICALIZATION OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN ANTI-APARTHEID CHURCH STRUGGLE by MIGUEL RODRIGUEZ B.S. University of Central Florida, 1997 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Miguel Rodriguez ii ABSTRACT This paper is intended to analyze the contributions of Contextual Theology and Contextual theologians to dismantling the South African apartheid system. It is intended to demonstrate that the South African churches failed to effectively politicize and radicalize to confront the government until the advent of Contextual Theology in South Africa. Contextual Theology provided the Christian clergy the theological justification to unite with anti-apartheid organizations. -

VOLUME the University of the State of New York 2 of 2 REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION DBQ

FOR TEACHERS ONLY VOLUME The University of the State of New York 2 OF 2 REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION DBQ GLOBAL HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Thursday, August 16, 2012 — 12:30 to 3:30 p.m., only RATING GUIDE FOR PART III A AND PART III B (DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTION) Updated information regarding the rating of this examination may be posted on the New York State Education Department’s web site during the rating period. Visit the site at: http://www.p12.nysed.gov/apda/ and select the link “Scoring Information” for any recently posted information regarding this examination. This site should be checked before the rating process for this examination begins and several times throughout the Regents Examination period. Contents of the Rating Guide For Part III A Scaffold (open-ended) questions: • A question-specific rubric For Part III B (DBQ) essay: • A content-specific rubric • Prescored answer papers. Score levels 5 and 1 have two papers each, and score levels 4, 3, and 2 have three papers each. They are ordered by score level from high to low. • Commentary explaining the specific score awarded to each paper • Five prescored practice papers General: • Test Specifications • Web addresses for the test-specific conversion chart and teacher evaluation forms Mechanics of Rating The procedures on page 2 are to be used in rating papers for this examination. More detailed directions for the organization of the rating process and procedures for rating the examination are included in the Information Booklet for Scoring the Regents Examination in Global History and Geography and United States History and Government.