1 Introduction: Negotiating Citizenship 2 Negotiating Citizenship in an Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Official Programme

The Society for Socialist Studies Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Canada June 4-6, 2019 The UBC Vancouver campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The circuits of financialised capitalism birthed by neoliberal capitalism have brought us to today’s historical moment of radical domestic and international inequality and with the existential threat of global warming. Much of the world is experiencing war and ongoing conflict, including genocide and apartheid, as new powers challenge the historic dominance of the West. Unnatural disasters threaten human and other life on planet Earth. A very small proportion of humanity holds most of the wealth and the world’s resources while others live in misery. There are new, bold expressions of old hatreds. Socialisms in all their variety matter today because they seek justice and peace for humanity, which is only possible through sustainable relationships with the natural world of which we are all a part. These struggles demand critical analyses of the unequal and ecologically destructive world we have inherited, as well as practices that prefigure a more just world to come in new circles of solidarity. For more than 50 years, the Society for Socialist Studies has endeavoured to open and maintain spaces for socialist and allied critical analyses and reflection, among both scholars and activists. -

Program at a Glance

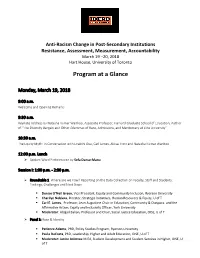

Anti-Racism Change in Post-Secondary Institutions Resistance, Assessment, Measurement, Accountability March 19 –20, 2018 Hart House, University of Toronto Program at a Glance Monday, March 19, 2018 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks 9:30 a.m. Keynote Address by Natasha Kumar Warikoo, Associate Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Author of “The Diversity Bargain and Other Dilemmas of Race, Admissions, and Meritocracy at Elite University” 10:30 a.m. The Equity Myth: In Conversation with Enakshi Dua, Carl James, Alissa Trotz and Natasha Kumar Warikoo 12:00 p.m. Lunch Spoken Word Performance by Sefa Danso-Manu Session I: 1:00 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. Roundtable 1: Where are we now? Reporting on the Data Collection on Faculty, Staff and Students: Findings, Challenges and Next Steps . Denise O’Neil Green, Vice President, Equity and Community Inclusion, Ryerson University . Cherilyn Nobleza, Director, Strategic Initiatives, Human Resources & Equity, U of T . Carl E. James, Professor, Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, and the Affirmative Action, Equity and Inclusivity Officer, York University . Moderator: Abigail Bakan, Professor and Chair, Social Justice Education, OISE, U of T Panel 1: Race & Identity . Patience Adamu, PhD, Policy Studies Program, Ryerson University . Paula DaCosta, PhD, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, OISE, U of T . Moderator: Janice Asiimwe M.Ed, Student Development and Student Services in Higher, OISE, U of T Panel 2: Celebrating 10 years of the SOAR Indigenous Youth Gathering . Susan Lee, Assistant Director, Culture & Community, Rotman School of Management . Eleni Vlahiotis, MoveU and Equity Movement Coordinator, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, U of T . -

Marxism and Anti-Racism: a Contribution to the Dialogue

Marxism and Anti-Racism: A Contribution to the Dialogue Abigail B. Bakan Department of Political Studies Queen's University Kingston, Ontario A Paper Presented to the Annual General Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association and the Society for Socialist Studies York University Toronto, Ontario June, 2006 Draft only. Not for quotation without written permission from the author. 2 Introduction: The Need for a Dialogue The need for an extended dialogue between Marxism and anti-racism emerges from several points of entry. 1 It is motivated in part by a perceptible distance between these two bodies of thought, sometimes overt, sometimes more ambiguous. For example, Cedric J. Robinson, in his influential work, Black Marxism, stresses the inherent incompatibility of the two paradigms, though the title of his classic work suggests a contribution to a new synthesis. While emphasizing the historic divide, Robinson devotes considerable attention to the ground for commonality, including the formative role of Marxism in the anti-racist theories of authors and activists such as C.L.R. James and W. E. B. Dubois.2 In recent debates, anti-racist theorists such as Edward Said has rejected the general framework of Marxism, but are drawn to some Marxists such as Gramsci and Lukacs.3 There is also, however, a rich body of material that presumes a seamless integration between Marxism and anti-racism, including those such as Angela Davis, Eugene Genovese and Robin Blackburn.4 Identifying points of similarity and discordance between Marxism and anti-racism suggests the need for dialogue in order to achieve either some greater and more coherent synthesis, or, alternatively, to more clearly define the boundaries of distinct lines of inquiry. -

The Appeal of Israel: Whiteness, Anti-Semitism, and the Roots of Diaspora Zionism in Canada

THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA by Corey Balsam A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Corey Balsam 2011 THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA Master of Arts 2011 Corey Balsam Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the appeal of Israel and Zionism for Ashkenazi Jews in Canada. The origins of Diaspora Zionism are examined using a genealogical methodology and analyzed through a bricolage of theoretical lenses including post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, and critical race theory. The active maintenance of Zionist hegemony in Canada is also explored through a discourse analysis of several Jewish-Zionist educational programs. The discursive practices of the Jewish National Fund and Taglit Birthright Israel are analyzed in light of some of the factors that have historically attracted Jews to Israel and Zionism. The desire to inhabit an alternative Jewish subject position in line with normative European ideals of whiteness is identified as a significant component of this attraction. It is nevertheless suggested that the appeal of Israel and Zionism is by no means immutable and that Jewish opposition to Zionism is likely to only increase in the coming years. ii Acknowledgements This thesis was not just written over the duration of my master’s degree. It is a product of several years of thinking and conversing with friends, family, and colleagues who have both inspired and challenged me to develop the ideas presented here. -

A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel Abigail F. Kolker The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2567 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE POTENCY OF POLICY?: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FILIPINO ELDER CARE WORKERS IN THE UNITED STATES AND ISRAEL by ABIGAIL F. KOLKER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Abigail F. Kolker All Rights Reserved ii The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F. Kolker This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ _____________________ Date Nancy Foner Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________ Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Richard Alba Philip Kasinitz Julia Wrigley THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F. -

Annual Report of the Jackman Humanities Institute 2014-2015

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE JACKMAN HUMANITIES INSTITUTE 2014-2015 KELLY MARK, CHESS SET, 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS: JACKMAN HUMANITIES INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT, 2014-2015 1. Overview 2014-2015 1 1.1. Annual Theme: Humour, Play, and Games 2 1.2. Art at the Institute: “This Area is Under 23 Hour Video and Audio Surveillance” 3 1.3. Summer Institute for Teachers (2-11 July 2014) 4 2. Message from the Director of the Jackman Humanities Institute 5 3. New Directions and Initiatives 8 3.1. Jackman Humanities Institute Workshops 9 3.1.1. Freedom and the University’s Responsibility (12-13 April 2015) 9 3.1.2. New Directions for Graduate Education in the Humanities (16-17 April, 21-22 May 2015) 10 3.1.3. Global Forum for New Visions in Humanities Research (1-2 June 2015) 13 3.1.4. Public Humanities (9-10 June 2015) 14 3.2. Digital Humanities Initiatives 16 3.2.1. Digital Humanities Census 16 3.2.2. Parker’s Scribes – Annotating Early Printed Books 17 3.2.3. Zotero workshop 17 3.2.4. CLIR Postdoctoral Fellows 17 3.3. Collaborative Initiatives 18 3.3.1. Cities of Learning: The University in the Americas 18 3.3.2. Handspring Theatre 19 4. Fellows 20 4.1. Jackman Humanities Institute Circle of Fellows 21 4.2. Chancellor Jackman Faculty Research Fellows in the Humanities 23 4.2.1. 2014-2015 Reports of Twelve-Month Fellows 24 4.2.2. 2014-2015 Reports of Six-Month Fellows 30 4.2.3. Courses Taught as a Result of Research by 12-month Research Fellows 32 4.3. -

On Pacification

On Pacification Socialist Studies Winter 2013 Artwork: “Days of Fire” www.socialiststudies.com © Copyright Pat Thornton SOCIALIST STUDIES ÉTUDES SOCIALISTES The Journal of the Society for Socialist Studies Revue de la Société d’études socialistes An Interdisciplinary Open-Access Journal www.socialiststudies.com Volume 9, Number 2 Winter 2013 ON PACIFICATION Socialist Studies/Études socialistes is a peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary and open-access journal with a focus on describing and analysing social, economic and/or political injustice, and practices of struggle, transformation, and liberation. Socialist Studies/Études socialistes is indexed in EBSCO Publishing, Left Index and the Wilson Social Sciences Full Text databases and is a member of the Canadian Association of Learned Journals (CALJ). Socialist Studies/Études socialistes is published by the Society for Socialist Studies. The Society for Socialist Studies (SSS) is an association of progressive academics, students, activists and members of the general public. Formed in 1966, the Society’s purpose is to facilitate and encourage research and analysis with an emphasis on socialist, feminist, ecological, and anti- racist points of view. The Society for Socialist Studies is an independent academic association and is not affiliated with any political organization or group. The Society is a member of the Canadian Federation for Humanities and Social Sciences (CFHSS) and meets annually as part ofthe Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences. For further information on the Society -

CONSTRUCTING the NATION THROUGH IMMIGRA Non LAW and LEGAL PROCESSES of BELONGING

CONSTRUCTING THE NATION THROUGH IMMIGRA nON LAW AND LEGAL PROCESSES OF BELONGING by Valerie Molina, BA, University of Western Ontario, 2010 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In the Program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Valerie Molina 2011 pnopffi1'V OF -- flYERSON Ufi:VERSITY 1I3RARY - Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature I further authOlize Ryerson University to reproduce this paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. 11 CONSTRUCTING THE NATION THROUGH IMMIGRA TION LAW AND LEGAL PROCESSES OF BELONGING Valerie Molina Master of Arts, 2011 Immigration and Settlement Studies Ryerson University ABSTRACT The aim ofthis critical literature review is to define the connection between immigration policies and the construction of a national identity, and to discuss what the implications of such connections may be. Tracing how the legal subjectivity of the migrant has developed throughout time and through policy reveals how messages about the nation and Others are created, sustained, and circulated through legal policies. What values are implicit within Canadian immigration policy? How does the migrant 'other' help 'us' stay 'us'? How do nationalist ideologies construct the Other and how is this reflected in labour market segmentation? Constructing a national identity involves categorizing migrants into legal categories of belonging, a process in which historical positions of power are both legitimized and re-established through law. -

Shanti Irene Fernando, Phd, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Science and Humanities (FSSH) CURRICULUM VITAE A

Shanti Irene Fernando, PhD, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Science and Humanities (FSSH) CURRICULUM VITAE A. GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Contact Information: Faculty of Social Science & Humanities, University of Ontario Institute of Technology. 55 Bond Street East, Oshawa, ON, Canada L1H 7K4 (905) 721-8668, Ext.3809 email: [email protected] 2. Degrees : BA, (Hons). University of Toronto, Department of English/ Department of Political Science 1989; MA, University of Guelph, Department of Political Studies 1992 PhD, Queen’s University, Department of Political Studies, 2003; Thesis: Political Participation in the Multicultural City: A Case Study of Chinese Canadians and Chinese Americans in Toronto and Los Angeles Supervisor: Dr. Abigail Bakan 3. Employment History: 2009-present Assistant Professor of Social Science and Humanities, UOIT 2008-2009 Lecturer, Faculty of Criminology, Justice and Policy Studies, UOIT 2007-2008 Assistant Professor of Canadian Studies, Mount Allison University 2003-2007 Assistant Professor of Political Science, York University 4. Honours 2012 Extraordinary Partner Award from Canadian Mental Health Association Durham Region 2000 Visiting Scholar, University of California Los Angeles, School of Public Policy 1999 Donald Rickard Travel Award ( Canada– US Studies) 1998-1999 Queen’s Graduate Award 5. Professional Affiliations: 2012-present Member Canadian Association for the Study of Adult Education 2012-present Member Association of Canadian Studies 2010-present Member Canadian Ethnic Studies Association 1 -

Curriculum Vitae

Audrey Kobayashi - C.V. Page 1 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ May 2016 CURRICULUM VITAE Name AUDREY KOBAYASHI Address 54 Kensington Avenue Kingston, Ontario K7L 4B5 Telephone: 613-533-3035 FAX: 613-533-6122 e-mail: [email protected] Citizenship Canadian Languages English (fluent); Spanish (moderate speak, read, write); French (understand, read); Japanese (speak) EDUCATION 1983 PhD, Geography, University of California at Los Angeles Dissertation Title: Emigration to Canada from Kaideima, Japan, 1885-1950: An Analysis of Community and Landscape Change 1980-82 Research Fellow (non-degree), Department of Geography, Kyoto University 1978 M.A. Geography, The University of British Columbia 1976 B.A. Geography, The University of British Columbia 1971 Certificate in Business and Public Relations, Patricia Stevens Career College ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Since 1999 Queen’s University, Full Professor and Queen’s Research Chair, Department of Geography, Cross-appointed to Gender Studies 1994-99 Queen's University, Director, Department of Gender Studies, Cross-appointed Department of Geography 1990-94 McGill University, Associate Professor, tenured, Department of Geography, Cross- appointed East Asian Studies 1989-90 University College, London, Visiting Professor, Department of Geography 1984-90 McGill University, Assistant Professor, tenure-track, Department of Geography 1983-84 McGill University, Assistant Professor (one-year contract), Department of Geography 1982 Carleton University, -

Fall/Automne 2015

REVIEWS / COMPTES RENDUS Ian Milligan, Rebel Youth: 1960s Labour links with a decidedly older Left, particu- Unrest, Young Workers, and New larly that based in the labour movement. Leftists in English Canada (Vancouver: Although these links were complex and University of British Columbia Press often fraught with conflict, they were an 2014) essential part of creating the Canadian New Left. While the historiography of the US To this developing body of New Left New Left is rich and varied enough to scholarship we can welcome the addi- have already gone through several waves tion of Ian Milligan’s Rebel Youth: 1960s of revision, scholarship on the Canadian Labour Unrest, Young Workers, and New New Left has been sparse. With the no- Leftists in English Canada. Milligan’s table exception of studies of Québécois book aims to “demonstrate the salience nationalism and the Quiet Revolution, of labour and how this significantly af- relatively little has been written about the fected the direction of radical and not-so- panoply of movements that erupted and radical political and cultural movements flamed out across English and French through the long sixties.” (11) While Canada over the course of the 1960s and campus revolts must be part of any tell- early 1970s. To the extent that such schol- ing of the New Left’s story, and are cer- arship exists, it has focused largely on the tainly featured in Rebel Youth, Milligan’s student-led and “new social movement” focus extends far beyond the universities. aspects of the New Left. Here the domi- He argues that understanding what was nant narrative has been one of “children happening in the workplace was central of privilege” rejecting the values of their to understanding the New Left. -

(Re)Negotiated Identifications: Reproducing and Challenging the Meanings of Arab, Canadian, and Arab Canadian Identities in Ottawa

(Re)negotiated Identifications: Reproducing and Challenging the Meanings of Arab, Canadian, and Arab Canadian Identities in Ottawa by Samah Sabra A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fiilfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011, Samah Sabra Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87751-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87751-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.