Fall/Automne 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

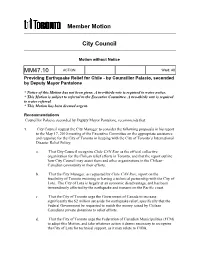

Member Motion City Council MM47.10

Member Motion City Council Motion without Notice MM47.10 ACTION Ward: All Providing Earthquake Relief for Chile - by Councillor Palacio, seconded by Deputy Mayor Pantalone * Notice of this Motion has not been given. A two-thirds vote is required to waive notice. * This Motion is subject to referral to the Executive Committee. A two-thirds vote is required to waive referral. * This Motion has been deemed urgent. Recommendations Councillor Palacio, seconded by Deputy Mayor Pantalone, recommends that: 1. City Council request the City Manager to consider the following proposals in his report to the May 17, 2010 meeting of the Executive Committee on the appropriate assistance and response for the City of Toronto in keeping with the City of Toronto’s International Disaster Relief Policy: a. That City Council recognize Chile CAN Rise as the official collective organization for the Chilean relief efforts in Toronto, and that the report outline how City Council may assist them and other organizations in the Chilean- Canadian community in their efforts. b. That the City Manager, as requested by Chile CAN Rise, report on the feasibility of Toronto twinning or having a technical partnership with the City of Lota. The City of Lota is largely at an economic disadvantage, and has been tremendously affected by the earthquake and tsunami on the Pacific coast. c. That the City of Toronto urge the Government of Canada to increase significantly the $2 million set aside for earthquake relief, specifically that the Federal Government be requested to match the money raised by Chilean Canadians private donations to relief efforts. -

Download Official Programme

The Society for Socialist Studies Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Canada June 4-6, 2019 The UBC Vancouver campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The circuits of financialised capitalism birthed by neoliberal capitalism have brought us to today’s historical moment of radical domestic and international inequality and with the existential threat of global warming. Much of the world is experiencing war and ongoing conflict, including genocide and apartheid, as new powers challenge the historic dominance of the West. Unnatural disasters threaten human and other life on planet Earth. A very small proportion of humanity holds most of the wealth and the world’s resources while others live in misery. There are new, bold expressions of old hatreds. Socialisms in all their variety matter today because they seek justice and peace for humanity, which is only possible through sustainable relationships with the natural world of which we are all a part. These struggles demand critical analyses of the unequal and ecologically destructive world we have inherited, as well as practices that prefigure a more just world to come in new circles of solidarity. For more than 50 years, the Society for Socialist Studies has endeavoured to open and maintain spaces for socialist and allied critical analyses and reflection, among both scholars and activists. -

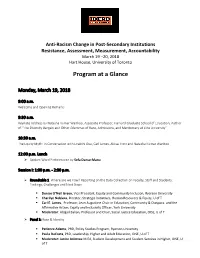

Program at a Glance

Anti-Racism Change in Post-Secondary Institutions Resistance, Assessment, Measurement, Accountability March 19 –20, 2018 Hart House, University of Toronto Program at a Glance Monday, March 19, 2018 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks 9:30 a.m. Keynote Address by Natasha Kumar Warikoo, Associate Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Author of “The Diversity Bargain and Other Dilemmas of Race, Admissions, and Meritocracy at Elite University” 10:30 a.m. The Equity Myth: In Conversation with Enakshi Dua, Carl James, Alissa Trotz and Natasha Kumar Warikoo 12:00 p.m. Lunch Spoken Word Performance by Sefa Danso-Manu Session I: 1:00 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. Roundtable 1: Where are we now? Reporting on the Data Collection on Faculty, Staff and Students: Findings, Challenges and Next Steps . Denise O’Neil Green, Vice President, Equity and Community Inclusion, Ryerson University . Cherilyn Nobleza, Director, Strategic Initiatives, Human Resources & Equity, U of T . Carl E. James, Professor, Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, and the Affirmative Action, Equity and Inclusivity Officer, York University . Moderator: Abigail Bakan, Professor and Chair, Social Justice Education, OISE, U of T Panel 1: Race & Identity . Patience Adamu, PhD, Policy Studies Program, Ryerson University . Paula DaCosta, PhD, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, OISE, U of T . Moderator: Janice Asiimwe M.Ed, Student Development and Student Services in Higher, OISE, U of T Panel 2: Celebrating 10 years of the SOAR Indigenous Youth Gathering . Susan Lee, Assistant Director, Culture & Community, Rotman School of Management . Eleni Vlahiotis, MoveU and Equity Movement Coordinator, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, U of T . -

Writing Beyond the End Times? the Literatures of Canada and Quebec

canadiana oenipontana 14 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Marie Carrière (eds.) Écrire au-delà de la fin des temps ? Les littératures au Canada et au Québec Writing Beyond the End Times? The Literatures of Canada and Quebec innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 14 Series Editor: Ursula Mathis-Moser innsbruck university press Ursula Mathis-Moser Institut für Romanistik, Zentrum für Kanadastudien, Universität Innsbruck Marie Carrière Canadian Literature Centre / Centre de littérature canadienne, University of Alberta Andrea Krotthammer Universität Innsbruck, redaktionelle Mitarbeit Supported by Gesellschaft für Kanada-Studien in den deutschsprachigen Ländern, Stadt Innsbruck, Zentrum für Kanadastudien der Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung der Universität Innsbruck © innsbruck university press, 2017 Universität Innsbruck 1st edition. All rights reserved. www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-903122-97-0 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Marie Carrière (eds.) Écrire au-delà de la fin des temps ? Les littératures au Canada et au Québec Writing Beyond the End Times? The Literatures of Canada and Quebec Table des matières – Contents Introduction – Introduction Ursula MATHIS-MOSER – Marie CARRIÈRE Écrire au-delà de la fin des temps ? Writing Beyond the End Times? ................................. 9 Apocalypse et dystopie – Apocalypse and Dystopia Dunja M. MOHR Anthropocene Fiction: Narrating the ‘Zero Hour’ in Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam Trilogy ............................................................................. 25 Nicole CÔTÉ Nouvelles -

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillrnent of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

Maintaining Ethnicity : A Case Study in the Maintenance of Ethnicity Among Chilean Immigrant Shidents By Stephanie A. Corlett, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillrnent of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario Novernber 1,2000 O 2000, Stephanie Corlett National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibiiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON KtAON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your fi& Votre refërmca Our rVe Notre rei8rence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author reîaim ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantiai extracts hmit Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenivise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, Abstract This thesis investigates the ways Chilean immigrant students perceive to maintain their ethnic identity within the mufticultural city of Ottawa. The data collected for this thesis spanned two years and is based on serni-stmctured interviews. -

University of Manitoba Press 301 St

University of Manitoba Press 301 St. John’s College, 92 Dysart Road UMP Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3T 2M5 1083120 University ofManitoba Press University 2014 Fall Subject Index Agriculture / 18 Autobiography / 9, 15 About U of M Press How to Order Contact Us Environment / 9, 18, 20 University of Manitoba Press is dedicated to producing books that combine Fiction / 6, 11 Gender Studies / 11 important new scholarship with a deep engagement in issues and events Geography / 9 that affect our lives. Founded in 1967, the Press is widely recognized Individuals Editorial Office History / 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, as a leading publisher of books on Aboriginal history, Native studies, U of M Press books are available at bookstores University of Manitoba Press 15, 16, 17, 19, 20 and Canadian history. As well, the Press is proud of its contribution to and on-line retailers across the country. 301 St. John’s College, 92 Dysart Rd., Winnipeg, MB R3T 2M5 Icelandic History / 8 Order through your local bookseller and Ph: 204-474-9495 Fax: 204-474-7566 Immigration / 3, 5, 10, 13, 16 immigration studies, ethnic studies, and the study of Canadian literature, save shipping charges, or order direct from www.uofmpress.ca Indigenous Studies / 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, culture, politics, and Aboriginal languages. The Press also publishes a 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20 wide-ranging list of books on the heritage of the peoples and land of the uofmpress.ca or one of our distributors listed Director: David Carr, [email protected] Literary Criticism / 1, 15, 19 Canadian prairies. -

Political Ideology and Heritage Language Development in a Chilean Exile Community: a Multiple Case Study

University of Alberta Political Ideology and Heritage Language Development in a Chilean Exile Community: A Multiple Case Study by Ava Becker A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics Modern Languages and Cultural Studies ©Ava Becker Spring 2013 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-92545-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-92545-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Public and Counterpublic Spaces in Dionne Brand's

DECENTRING MULTICULTURALISM: PUBLIC AND COUNTERPUBLIC SPACES IN DIONNE BRAND’S WHAT WE ALL LONG FOR AND TIMOTHY TAYLOR’S STANLEY PARK by Natasha Larissa Sharpe B.F.A, The University of Victoria, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The College of Graduate Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) November 2012 © Natasha Larissa Sharpe, 2012 ii Abstract This study explores the usage of public and counterpublic spaces in two Canadian novels, Dionne Brand‘s What We All Long For (2005) and Timothy Taylor‘s Stanley Park (2001). These navigations and explorations reconstitute public space in order to claim that space for marginalized Canadians, challenging the discourse of multicultural tolerance and constructions of Canadian identity as white. These texts challenge current understandings of citizenship based on exclusion in order to promote a citizenship predicated on civic engagement, coalition, and affinity, rather than essentialist identity. I undertake a close reading and comparison of both novels within the context of Canadian literary history, Canada‘s history of multicultural policy, and the intersections of multicultural discourse and Canadian literature, in particular the ways in which literature by Canadian authors designated as ‗multicultural‘ is appropriated by national multicultural discourse to promote Canadian tolerance and preserve white hegemony and centrality in Canada. My work draws upon theories of postcolonialism, postmodernism, and hybridity to explore race, gender, and class as they constitute subjects within relations of power in these novels. While Brand‘s characters at times seek refuge in subaltern counterpublics, they ultimately realize the limitations and failings of those spaces, opting instead to remake and reimagine the public in their own image as a space for civic engagement on their own terms rather than those of the white, capitalist hegemony. -

Marxism and Anti-Racism: a Contribution to the Dialogue

Marxism and Anti-Racism: A Contribution to the Dialogue Abigail B. Bakan Department of Political Studies Queen's University Kingston, Ontario A Paper Presented to the Annual General Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association and the Society for Socialist Studies York University Toronto, Ontario June, 2006 Draft only. Not for quotation without written permission from the author. 2 Introduction: The Need for a Dialogue The need for an extended dialogue between Marxism and anti-racism emerges from several points of entry. 1 It is motivated in part by a perceptible distance between these two bodies of thought, sometimes overt, sometimes more ambiguous. For example, Cedric J. Robinson, in his influential work, Black Marxism, stresses the inherent incompatibility of the two paradigms, though the title of his classic work suggests a contribution to a new synthesis. While emphasizing the historic divide, Robinson devotes considerable attention to the ground for commonality, including the formative role of Marxism in the anti-racist theories of authors and activists such as C.L.R. James and W. E. B. Dubois.2 In recent debates, anti-racist theorists such as Edward Said has rejected the general framework of Marxism, but are drawn to some Marxists such as Gramsci and Lukacs.3 There is also, however, a rich body of material that presumes a seamless integration between Marxism and anti-racism, including those such as Angela Davis, Eugene Genovese and Robin Blackburn.4 Identifying points of similarity and discordance between Marxism and anti-racism suggests the need for dialogue in order to achieve either some greater and more coherent synthesis, or, alternatively, to more clearly define the boundaries of distinct lines of inquiry. -

Immigrants Not Natives — Centre for Internet and Society

Immigrants not Natives — Centre for Internet and Society http://cis-india.org/digital-natives/media-coverage/immigrants-not-natives Blog Events Media Coverage & Reviews Digital Natives Newsletter Pathways to Higher Education Sign Up! Digital Natives updates and Immigrants not Natives by Sally Wyatt — last modified Apr 30, 2012 06:27 PM alerts Sally Wyatt reviews the four-book collective, Digital AlterNatives with a Cause? edited by Nishant Shah & Fieke Jansen. Review of Digital AlterNatives with a Cause? edited by Nishant Shah & Fieke Jansen, Bangalore: Centre for Internet and Society/The Hague: Hivos Knowledge Programme, 2011: Twitter Digital AlterNatives with a Cause? (2011) is the product of a series of workshops held in 2010-11 in Taiwan, South Africa and Chile. The aim was to bring together a different cohort of ‘digital natives’ than that which had hitherto been assumed in the popular and academic literature, namely white, highly educated, (mostly) male elites largely to be found on and around US university campuses. The workshops brought together 80 people who identified themselves as ‘digital natives’ but with very different backgrounds, and benjamintomkins : As who came from Asia, Africa and Latin America. The four booklets which have been produced on the themes of ‘To Be’, ‘To Think’, #digitalnatives evolve http://t.co /yuTGz9eDOb @HannaRosin ‘To Act’ and ‘To Connect’ provide many fascinating and thought-provoking insights into the possibilities for reflection, action and explores #digital tech impact on interaction available to this group. #child development http://t.co /tYf7X64u4p In my review, I focus on the editorial comments provided by Nishant Shah and Fieke Jansen in the Preface, the Introduction, and Mar 22, 2013 07:13 AM the sidebar text running alongside most of Book One, To Be, in which they provide the context for the workshops and the books, and in which they reflect on the concept of ‘digital native’. -

The Appeal of Israel: Whiteness, Anti-Semitism, and the Roots of Diaspora Zionism in Canada

THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA by Corey Balsam A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Corey Balsam 2011 THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA Master of Arts 2011 Corey Balsam Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the appeal of Israel and Zionism for Ashkenazi Jews in Canada. The origins of Diaspora Zionism are examined using a genealogical methodology and analyzed through a bricolage of theoretical lenses including post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, and critical race theory. The active maintenance of Zionist hegemony in Canada is also explored through a discourse analysis of several Jewish-Zionist educational programs. The discursive practices of the Jewish National Fund and Taglit Birthright Israel are analyzed in light of some of the factors that have historically attracted Jews to Israel and Zionism. The desire to inhabit an alternative Jewish subject position in line with normative European ideals of whiteness is identified as a significant component of this attraction. It is nevertheless suggested that the appeal of Israel and Zionism is by no means immutable and that Jewish opposition to Zionism is likely to only increase in the coming years. ii Acknowledgements This thesis was not just written over the duration of my master’s degree. It is a product of several years of thinking and conversing with friends, family, and colleagues who have both inspired and challenged me to develop the ideas presented here. -

A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel Abigail F. Kolker The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2567 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE POTENCY OF POLICY?: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FILIPINO ELDER CARE WORKERS IN THE UNITED STATES AND ISRAEL by ABIGAIL F. KOLKER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Abigail F. Kolker All Rights Reserved ii The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F. Kolker This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ _____________________ Date Nancy Foner Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________ Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Richard Alba Philip Kasinitz Julia Wrigley THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F.