Marxism and Anti-Racism: a Contribution to the Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Official Programme

The Society for Socialist Studies Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Canada June 4-6, 2019 The UBC Vancouver campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The circuits of financialised capitalism birthed by neoliberal capitalism have brought us to today’s historical moment of radical domestic and international inequality and with the existential threat of global warming. Much of the world is experiencing war and ongoing conflict, including genocide and apartheid, as new powers challenge the historic dominance of the West. Unnatural disasters threaten human and other life on planet Earth. A very small proportion of humanity holds most of the wealth and the world’s resources while others live in misery. There are new, bold expressions of old hatreds. Socialisms in all their variety matter today because they seek justice and peace for humanity, which is only possible through sustainable relationships with the natural world of which we are all a part. These struggles demand critical analyses of the unequal and ecologically destructive world we have inherited, as well as practices that prefigure a more just world to come in new circles of solidarity. For more than 50 years, the Society for Socialist Studies has endeavoured to open and maintain spaces for socialist and allied critical analyses and reflection, among both scholars and activists. -

Program at a Glance

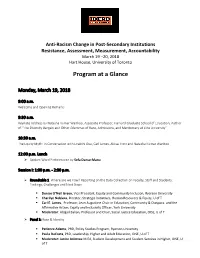

Anti-Racism Change in Post-Secondary Institutions Resistance, Assessment, Measurement, Accountability March 19 –20, 2018 Hart House, University of Toronto Program at a Glance Monday, March 19, 2018 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks 9:30 a.m. Keynote Address by Natasha Kumar Warikoo, Associate Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Author of “The Diversity Bargain and Other Dilemmas of Race, Admissions, and Meritocracy at Elite University” 10:30 a.m. The Equity Myth: In Conversation with Enakshi Dua, Carl James, Alissa Trotz and Natasha Kumar Warikoo 12:00 p.m. Lunch Spoken Word Performance by Sefa Danso-Manu Session I: 1:00 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. Roundtable 1: Where are we now? Reporting on the Data Collection on Faculty, Staff and Students: Findings, Challenges and Next Steps . Denise O’Neil Green, Vice President, Equity and Community Inclusion, Ryerson University . Cherilyn Nobleza, Director, Strategic Initiatives, Human Resources & Equity, U of T . Carl E. James, Professor, Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, and the Affirmative Action, Equity and Inclusivity Officer, York University . Moderator: Abigail Bakan, Professor and Chair, Social Justice Education, OISE, U of T Panel 1: Race & Identity . Patience Adamu, PhD, Policy Studies Program, Ryerson University . Paula DaCosta, PhD, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, OISE, U of T . Moderator: Janice Asiimwe M.Ed, Student Development and Student Services in Higher, OISE, U of T Panel 2: Celebrating 10 years of the SOAR Indigenous Youth Gathering . Susan Lee, Assistant Director, Culture & Community, Rotman School of Management . Eleni Vlahiotis, MoveU and Equity Movement Coordinator, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, U of T . -

A Socialist Schism

A Socialist Schism: British socialists' reaction to the downfall of Milošević by Andrew Michael William Cragg Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Marsha Siefert Second Reader: Professor Vladimir Petrović CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This work charts the contemporary history of the socialist press in Britain, investigating its coverage of world events in the aftermath of the fall of state socialism. In order to do this, two case studies are considered: firstly, the seventy-eight day NATO bombing campaign over the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, and secondly, the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević in October of 2000. The British socialist press analysis is focused on the Morning Star, the only English-language socialist daily newspaper in the world, and the multiple publications affiliated to minor British socialist parties such as the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain (Provisional Central Committee). The thesis outlines a broad history of the British socialist movement and its media, before moving on to consider the case studies in detail. -

Chris Harman

How Marxism Works Chris Harman How Marxism Works - Chris Harman First published May 1979 Fifth edition published July 1997 Sixth edition published July 2000 Bookmarks Publications Ltd, c/o 1 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3QE, England Bookmarks, PO Box 16085, Chicago, Illinois 60616, USA Bookmarks, PO Box A338, Sydney South, NSW 2000, Australia Copyright © Bookmarks Publications Ltd ISBN 1 898876 27 4 This online edition prepared by Marc Newman Contents Introduction 7 1 Why we need Marxist theory 9 2 Understanding history 15 3 Class struggle 25 4 Capitalism—how the system began 31 5 The labour theory of value 39 6 Economic crisis 45 7 The working class 51 8 How can society be changed? 55 9 How do workers become revolutionary? 65 10 The revolutionary socialist party 69 11 Imperialism and national liberation 73 12 Marxism and feminism 79 13 Socialism and war 83 Further reading 87 Introduction There is a widespread myth that Marxism is difficult. It is a myth propagated by the enemies of socialism – former Labour leader Harold Wilson boasted that he was never able to get beyond the first page of Marx’s Capital. It is a myth also encouraged by a peculiar breed of academics who declare themselves to be ‘Marxists’: they deliberately cultivate obscure phrases and mystical expressions in order to give the impression that they possess a special knowledge denied to others. So it is hardly surprising that many socialists who work 40 hours a week in factories, mines or offices take it for granted that Marxism is something they will never have the time or the opportunity to understand. -

A People's History of the World

A people’s history of the world A people’s history of the world Chris Harman London, Chicago and Sydney A People’s History of the World – Chris Harman First published 1999 Reprinted 2002 Bookmarks Publications Ltd, c/o 1 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3QE, England Bookmarks, PO Box 16085, Chicago, Illinois 60616, USA Bookmarks, PO Box A338, Sydney South, NSW 2000, Australia Copyright © Bookmarks Publications Ltd ISBN 1 898876 55 X Printed by Interprint Limited, Malta Cover by Sherborne Design Bookmarks Publications Ltd is linked to an international grouping of socialist organisations: I Australia: International Socialist Organisation, PO Box A338, Sydney South. [email protected] I Austria: Linkswende, Postfach 87, 1108 Wien. [email protected] I Britain: Socialist Workers Party, PO Box 82, London E3 3LH. [email protected] I Canada: International Socialists, PO Box 339, Station E, Toronto, Ontario M6H 4E3. [email protected] I Cyprus: Ergatiki Demokratia, PO Box 7280, Nicosia. [email protected] I Czech Republic: Socialisticka Solidarita, PO Box 1002, 11121 Praha 1. [email protected] I Denmark: Internationale Socialister, PO Box 5113, 8100 Aarhus C. [email protected] I Finland: Sosialistiliitto, PL 288, 00171 Helsinki. [email protected] I France: Socialisme par en bas, BP 15-94111, Arcueil Cedex. [email protected] I Germany: Linksruck, Postfach 304 183, 20359 Hamburg. [email protected] I Ghana: International Socialist Organisation, PO Box TF202, Trade Fair, Labadi, Accra. I Greece: Sosialistiko Ergatiko Komma, c/o Workers Solidarity, PO Box 8161, Athens 100 10. [email protected] I Holland: Internationale Socialisten, PO Box 92025, 1090AA Amsterdam. -

Chronological Index of Miscellaneous Anti-Fascist Pamphlets and Leaflets

Chronological index of miscellaneous anti-fascist pamphlets and leaflets 1925-1945 Leaflets: No justice for Labour!: fascists admit robbery with violence and are Fascism Box 8 discharged! (1925) The fruits of fascism (Labour Party, 1933) Labour Party Box 23 The spotlight on the Blackshirts: who are these Blackshirts? (Labour Labour Party Box 23 Party, 1934) (Labour Leaflet 29) Trade union officials arrested: branches, area committees dissolved Fascism Box 8 (Anti-Fascist Relief Committee, ca. 1936) Do you know these facts about Mosley and his Fascists? (Woburn Press, Fascism Box 8 ca. 1936 Jewish People's Council against Fascism and Anti-Semitism and the Fascism Box 2 Board of Deputies (Jewish People's Council against Fascism and Anti- Semitism, ca. 1936) Fascism: fight it now (Labour Research Department, 1937) Labour Research Department The BUF and anti-semitism: an exposure (CH Lane, ca. 1937) Fascism Box 1 Britain's fifth column: a plain warning! (Anchor Press, 1940) Fascism Box 1 The menace of fascism! (Kersal Jewish Discussion Circle, no date) Fascism Box 3 Pamphlets: The truth about the New Party, by Cecil Melville (Lawrence and Wishart, Fascism Box 8 1931) The burning of the Reichstag: official findings of the Legal Commission of Fascism Box 1 Inquiry Sep 1933 (Relief Committee of the Victims Of German Fascism, 1933) Democracy and fascism: a reply to the Labour manifesto on "Democracy Communist Party of versus dictatorship" by R Palme Dutt (Communist Party of Great Britain, Great Britain Box 3 ca. 1933) Feed the children: what is being done to relieve the victims of the fascist Fascism Box 1 regime by Ellen Wilkinson (International Committee for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism, ca. -

The Appeal of Israel: Whiteness, Anti-Semitism, and the Roots of Diaspora Zionism in Canada

THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA by Corey Balsam A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Corey Balsam 2011 THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA Master of Arts 2011 Corey Balsam Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the appeal of Israel and Zionism for Ashkenazi Jews in Canada. The origins of Diaspora Zionism are examined using a genealogical methodology and analyzed through a bricolage of theoretical lenses including post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, and critical race theory. The active maintenance of Zionist hegemony in Canada is also explored through a discourse analysis of several Jewish-Zionist educational programs. The discursive practices of the Jewish National Fund and Taglit Birthright Israel are analyzed in light of some of the factors that have historically attracted Jews to Israel and Zionism. The desire to inhabit an alternative Jewish subject position in line with normative European ideals of whiteness is identified as a significant component of this attraction. It is nevertheless suggested that the appeal of Israel and Zionism is by no means immutable and that Jewish opposition to Zionism is likely to only increase in the coming years. ii Acknowledgements This thesis was not just written over the duration of my master’s degree. It is a product of several years of thinking and conversing with friends, family, and colleagues who have both inspired and challenged me to develop the ideas presented here. -

A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel Abigail F. Kolker The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2567 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE POTENCY OF POLICY?: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FILIPINO ELDER CARE WORKERS IN THE UNITED STATES AND ISRAEL by ABIGAIL F. KOLKER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Abigail F. Kolker All Rights Reserved ii The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F. Kolker This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ _____________________ Date Nancy Foner Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________ Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Richard Alba Philip Kasinitz Julia Wrigley THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F. -

Annual Report of the Jackman Humanities Institute 2014-2015

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE JACKMAN HUMANITIES INSTITUTE 2014-2015 KELLY MARK, CHESS SET, 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS: JACKMAN HUMANITIES INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT, 2014-2015 1. Overview 2014-2015 1 1.1. Annual Theme: Humour, Play, and Games 2 1.2. Art at the Institute: “This Area is Under 23 Hour Video and Audio Surveillance” 3 1.3. Summer Institute for Teachers (2-11 July 2014) 4 2. Message from the Director of the Jackman Humanities Institute 5 3. New Directions and Initiatives 8 3.1. Jackman Humanities Institute Workshops 9 3.1.1. Freedom and the University’s Responsibility (12-13 April 2015) 9 3.1.2. New Directions for Graduate Education in the Humanities (16-17 April, 21-22 May 2015) 10 3.1.3. Global Forum for New Visions in Humanities Research (1-2 June 2015) 13 3.1.4. Public Humanities (9-10 June 2015) 14 3.2. Digital Humanities Initiatives 16 3.2.1. Digital Humanities Census 16 3.2.2. Parker’s Scribes – Annotating Early Printed Books 17 3.2.3. Zotero workshop 17 3.2.4. CLIR Postdoctoral Fellows 17 3.3. Collaborative Initiatives 18 3.3.1. Cities of Learning: The University in the Americas 18 3.3.2. Handspring Theatre 19 4. Fellows 20 4.1. Jackman Humanities Institute Circle of Fellows 21 4.2. Chancellor Jackman Faculty Research Fellows in the Humanities 23 4.2.1. 2014-2015 Reports of Twelve-Month Fellows 24 4.2.2. 2014-2015 Reports of Six-Month Fellows 30 4.2.3. Courses Taught as a Result of Research by 12-month Research Fellows 32 4.3. -

On Pacification

On Pacification Socialist Studies Winter 2013 Artwork: “Days of Fire” www.socialiststudies.com © Copyright Pat Thornton SOCIALIST STUDIES ÉTUDES SOCIALISTES The Journal of the Society for Socialist Studies Revue de la Société d’études socialistes An Interdisciplinary Open-Access Journal www.socialiststudies.com Volume 9, Number 2 Winter 2013 ON PACIFICATION Socialist Studies/Études socialistes is a peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary and open-access journal with a focus on describing and analysing social, economic and/or political injustice, and practices of struggle, transformation, and liberation. Socialist Studies/Études socialistes is indexed in EBSCO Publishing, Left Index and the Wilson Social Sciences Full Text databases and is a member of the Canadian Association of Learned Journals (CALJ). Socialist Studies/Études socialistes is published by the Society for Socialist Studies. The Society for Socialist Studies (SSS) is an association of progressive academics, students, activists and members of the general public. Formed in 1966, the Society’s purpose is to facilitate and encourage research and analysis with an emphasis on socialist, feminist, ecological, and anti- racist points of view. The Society for Socialist Studies is an independent academic association and is not affiliated with any political organization or group. The Society is a member of the Canadian Federation for Humanities and Social Sciences (CFHSS) and meets annually as part ofthe Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences. For further information on the Society -

Socialists of the World Support Heloisa Helena

Socialists of the World Support Heloisa Helena https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article1098 Brazil Socialists of the World Support Heloisa Helena - News from around the world - Publication date: Monday 7 August 2006 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/15 Socialists of the World Support Heloisa Helena Many of us signed, two years ago, a protest against the exclusion of Heloisa Helena and other members of parliament from the PT, the Brazilian Workers Party. [https://internationalviewpoint.org/IMG/jpg/hh2-2.jpg] Today, Heloisa has become the presidential candidate of the new Party of Socialism and Liberty (PSOL), founded by several bureaucratically excluded or dissident members of the PT, and of a Left Front. While Lula's government followed a typical social-liberal course, disappointing millions of people who voted for him in the hope of a radical social and political change, and people all over the world who expected from Brazil a new impulse for anti-imperialist struggle, Heloisa Helena and her comrades remained faithful to the original anti-imperialist and socialist programme of the PT. She is today the only candidate in the Brazilian elections who raises the historical banners of the Brazilian labour movement, of the peasants, the poor and the oppressed: a radical agrarian reform, suspension of the payment of the foreign debt, rejection of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (ALCA), a substantial reduction of working hours without loss of pay, a moratorium on the use of Genetically Modified Organisms (such as Monsanto's Terminator seeds), support for the ALBA, the Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas (Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba). -

CONSTRUCTING the NATION THROUGH IMMIGRA Non LAW and LEGAL PROCESSES of BELONGING

CONSTRUCTING THE NATION THROUGH IMMIGRA nON LAW AND LEGAL PROCESSES OF BELONGING by Valerie Molina, BA, University of Western Ontario, 2010 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In the Program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Valerie Molina 2011 pnopffi1'V OF -- flYERSON Ufi:VERSITY 1I3RARY - Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature I further authOlize Ryerson University to reproduce this paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. 11 CONSTRUCTING THE NATION THROUGH IMMIGRA TION LAW AND LEGAL PROCESSES OF BELONGING Valerie Molina Master of Arts, 2011 Immigration and Settlement Studies Ryerson University ABSTRACT The aim ofthis critical literature review is to define the connection between immigration policies and the construction of a national identity, and to discuss what the implications of such connections may be. Tracing how the legal subjectivity of the migrant has developed throughout time and through policy reveals how messages about the nation and Others are created, sustained, and circulated through legal policies. What values are implicit within Canadian immigration policy? How does the migrant 'other' help 'us' stay 'us'? How do nationalist ideologies construct the Other and how is this reflected in labour market segmentation? Constructing a national identity involves categorizing migrants into legal categories of belonging, a process in which historical positions of power are both legitimized and re-established through law.