The Subaltern: Speaking Through Socialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Official Programme

The Society for Socialist Studies Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Canada June 4-6, 2019 The UBC Vancouver campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The circuits of financialised capitalism birthed by neoliberal capitalism have brought us to today’s historical moment of radical domestic and international inequality and with the existential threat of global warming. Much of the world is experiencing war and ongoing conflict, including genocide and apartheid, as new powers challenge the historic dominance of the West. Unnatural disasters threaten human and other life on planet Earth. A very small proportion of humanity holds most of the wealth and the world’s resources while others live in misery. There are new, bold expressions of old hatreds. Socialisms in all their variety matter today because they seek justice and peace for humanity, which is only possible through sustainable relationships with the natural world of which we are all a part. These struggles demand critical analyses of the unequal and ecologically destructive world we have inherited, as well as practices that prefigure a more just world to come in new circles of solidarity. For more than 50 years, the Society for Socialist Studies has endeavoured to open and maintain spaces for socialist and allied critical analyses and reflection, among both scholars and activists. -

Election Address: There Is a Socialist Alternative

Socialist Studies Election Address Socialist Studies No 95, Spring 2015 Oil, War and Capitalism Socialist Ideas and Understanding Marxism and Democracy Election Address: There Is A Philip Webb: Architecture and Socialism Socialist Alternative What we Said and When A Great Idea for the 21st Century The forthcoming May General Election will see a myriad of The Philosophy of Anarchism political parties asking the working class majority to vote for them Syriza and the Troika: A Modern Greek and their policies. Each political party will take capitalism for Tragedy granted, the class system as given and the private ownership of the means of production and distribution as natural, unquestionable and inviolable. Workers will be expected to vote for leaders who will claim they have a vision for a “better future” and the necessary skill to change and shape of society for the benefit of everyone. The propaganda of the capitalist political parties is that there is a fundamental difference between them and the other political parties who will be contesting the General Election. Labour will promise to “save the NHS from Tory privatisation” and to ease austerity measures. The Tories will say a vote for them is a vote for economic probity and lower taxation. The Liberal Democrats will try to tell workers that they “humanised” the Tories when in power and did a lot for the poor. The Greens will say they, and only they, can “save the planet” while UKIP will blame all societies’ problems on the European Union and the unrestrained movement of migrant labour into Britain. For the working class, that is, those who live on wages and salaries, to be taken in by this propaganda, is a big mistake. -

Stuart Hall: an Exemplary Socialist Public Intellectual?

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Communication Studies Faculty Publications Communication Studies Summer 2014 Stuart Hall: An Exemplary Socialist Public Intellectual? Herbert Pimlott Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/coms_faculty Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Other Communication Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pimlott, Herbert. 2014. "Stuart Hall: An Exemplary Socialist Public Intellectual?" Socialist Studies / Études socialistes 10 (1): 191-99. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Socialist Studies / Études socialistes 10 (1) Summer 2014 Copyright © 2014 The Author(s) Feature Contribution STUART HALL: AN EXEMPLARY SOCIALIST PUBLIC INTELLECTUAL? Herbert Pimlott,1 Department of Communication Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University Abstract Most assessments of the influence of scholars and public intellectuals focus on their ideas, which are based upon an implicit assumption that their widespread circulation are a result of the veracity and strength of the ideas themselves, rather than the processes of production and distribution, including the intellectual’s own contribution to the ideas’ popularity by attending conferences and public rallies, writing for periodicals, and so on. This concise article offers an assessment of the late Stuart Hall’s role as a socialist public intellectual by connecting the person, scholar and public intellectual to the organisations, institutions and publications through which his contributions to both cultural studies and left politics were produced and distributed. -

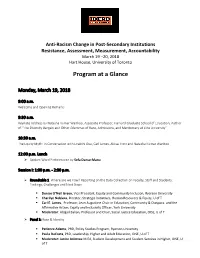

Program at a Glance

Anti-Racism Change in Post-Secondary Institutions Resistance, Assessment, Measurement, Accountability March 19 –20, 2018 Hart House, University of Toronto Program at a Glance Monday, March 19, 2018 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks 9:30 a.m. Keynote Address by Natasha Kumar Warikoo, Associate Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Author of “The Diversity Bargain and Other Dilemmas of Race, Admissions, and Meritocracy at Elite University” 10:30 a.m. The Equity Myth: In Conversation with Enakshi Dua, Carl James, Alissa Trotz and Natasha Kumar Warikoo 12:00 p.m. Lunch Spoken Word Performance by Sefa Danso-Manu Session I: 1:00 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. Roundtable 1: Where are we now? Reporting on the Data Collection on Faculty, Staff and Students: Findings, Challenges and Next Steps . Denise O’Neil Green, Vice President, Equity and Community Inclusion, Ryerson University . Cherilyn Nobleza, Director, Strategic Initiatives, Human Resources & Equity, U of T . Carl E. James, Professor, Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, and the Affirmative Action, Equity and Inclusivity Officer, York University . Moderator: Abigail Bakan, Professor and Chair, Social Justice Education, OISE, U of T Panel 1: Race & Identity . Patience Adamu, PhD, Policy Studies Program, Ryerson University . Paula DaCosta, PhD, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, OISE, U of T . Moderator: Janice Asiimwe M.Ed, Student Development and Student Services in Higher, OISE, U of T Panel 2: Celebrating 10 years of the SOAR Indigenous Youth Gathering . Susan Lee, Assistant Director, Culture & Community, Rotman School of Management . Eleni Vlahiotis, MoveU and Equity Movement Coordinator, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, U of T . -

An Anarchist Anthology. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004, 406 Pp, $29.95

105 BOOK REVIEW ALLAN ANTLIFF (Editor), Only a Beginning: An Anarchist Anthology. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004, 406 pp, $29.95. Reviewed by Richard J.F. Day, Queen’s University Only A Beginning looks like an ‘art book’, and in a certain sense that’s what it is. But it’s an a n a r c h i s t art book, or more precisely, an anarchist art h i s t o r y book, and that makes all the difference in the world. By focusing on events and issues relevant to the Canadian anarchist scene from 1976 to 2004, it provides an entrance into a world, or a world of worlds, that is almost completely absent from both the mass media and academic journals. The History section, which kicks off the collection, is in essence a retrospective of selected anarchist publications, with an emphasis on anti-civilizationist journals written in English and produced in Toronto, Va n c o u v e r, and Montreal during the 1980s. T h e r e is a bilingual entry for Montreal’s D é m a n a r c h i e and, overall, enough diversity of time and place to give the reader a strong sense of what Canadian anarchist publishers have been up to. Leafing through stacks of old newspapers is always intriguing, and with the help of excellent design and production values, Only A Beginning definitely gives one the sense of discovering a hidden archive. But what really made the first section a highlight of the book, for me, was hearing the voices of the people who were involved in the production process itself. -

Burn It Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985

Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 by Eryk Martin M.A., University of Victoria, 2008 B.A. (Hons.), University of Victoria, 2006 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Eryk Martin 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Eryk Martin Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Title: Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 Examining Committee: Chair: Dimitris Krallis Associate Professor Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor Roxanne Panchasi Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Professor Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Joan Sangster External Examiner Professor Gender and Women’s Studies Trent University Date Defended/Approved: January 15, 2016 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This dissertation investigates the experiences of five Canadian anarchists commonly knoWn as the Vancouver Five, Who came together in the early 1980s to destroy a BC Hydro power station in Qualicum Beach, bomb a Toronto factory that Was building parts for American cruise missiles, and assist in the firebombing of pornography stores in Vancouver. It uses these events in order to analyze the development and transformation of anarchist activism between 1967 and 1985. Focusing closely on anarchist ideas, tactics, and political projects, it explores the resurgence of anarchism as a vibrant form of leftWing activism in the late tWentieth century. In addressing the ideological basis and contested cultural meanings of armed struggle, it uncovers Why and how the Vancouver Five transformed themselves into an underground, clandestine force. -

Orwell George

The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume II: My Country Right or Left 1940-1943 by George Orwell Edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at EOF Back Cover: "He was a man, like Lawrence, whose personality shines out in everything he said or wrote." -- Cyril Connolly George Orwell requested in his will that no biography of him should be written. This collection of essays, reviews, articles, and letters which he wrote between the ages of seventeen and forty-six (when he died) is arranged in chronological order. The four volumes provide at once a wonderfully intimate impression of, and a "splendid monument" to, one of the most honest and individual writers of this century -- a man who forged a unique literary manner from the process of thinking aloud, who possessed an unerring gift for going straight to the point, and who elevated political writing to an art. The second volume principally covers the two years when George Orwell worked as a Talks Assistant (and later Producer) in the Indian section of the B.B.C. At the same time he was writing for Horizon, New Statesman and other periodicals. His war-time diaries are included here. Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia First published in England by Seeker & Warburg 1968 Published in Penguin Books 1970 Reprinted 1971 Copyright © Sonia Brownell Orwell, 1968 Made and printed in Great Britain by Hazell Watson & Viney Ltd, Aylesbury, Bucks Set in Linotype Times This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser Contents Acknowledgements A Note on the Editing 1940 1. -

In Bed with Capitalism

Socialist Studies In Bed With Capitalism [This is the web site of the reconstituted Socialist Party of Great Britain who were expelled from the Claphambased Socialist Party The Empire Strikes Back in May 1991 for using the name “The Socialist Party of Great Islamic Capitalism Britain” in our propaganda as required by Clause 6 of The Object The Left and Islamic Capitalism and Declaration of Principles formulated in 1904 to which we Government Expenditure agree. We reconstituted ourselves as The Socialist Party of Great How Socialism Will Happen Britain in June 1991. Any money given to us for literature or support is in recognition that we are not the Clapham based EU and World Capitalism Socialist Party at 52 Clapham High Street and any mistakes will be Stalin's Cult of The Individual rectified.] Tolpuddle and the Unions Desperate Spoiling Tactics Socialist Studies No.60, Summer 2006 The Dark Art of Black Propaganda Q and A: Immigration In Bed With Capitalism There is a cynical view of capitalist politics and the type of Labour politician who ends up a Minister of State which goes something like this: at 18 a dogmatic fanatic of a left wing political party; at 21 its leader; at 25 a radical researcher for a Labour Member of Parliament; at 30 a firebrand MP; at 35 a junior Minister with a lucrative consultancy in a PR firm, at 40 a Minister of State passing legislation no different from the Tory Party, to eventually become a Cabinet Minister who would ascent to go to war, to turn a blind eye to torture and to agree to use troops to break strikes. -

African Canadian Women and the Question of Identity

African Canadian Women and the Question of Identity Njoki Nathani Wane, Centre for Integrative Introduction Anti-Racist Research Studies (CIARS), "Black" and "woman" are the two words that immediately University of Toronto, conducts research and come to mind whenever I'm asked to describe myself. I teaches in the areas of Black feminisms in am always "Black" first and "female" second. Canada, African feminisms, African indigenous (Riviere 2004, 222) knowledges, anti-racist education in teacher education, African women and spirituality, and Canada is a nation that embraces ethno-medicine and has published widely on diversity and multiculturalism as its corner stone these topics. for building the sense of belonging for all her citizens. However, Himani Bannerji is quick to Abstract point out that, in her opinion, the notion of Canada is a nation that embraces diversity and diversity and multiculturalism, although multiculturalism as its corner stone for building characteristically "Canadian," do not effectively the sense of belonging for all her citizens. Many work in practice. She states: "It does not require Black Canadian women, however, feel much effort to realize that diversity is not equal excluded and not part of the Canadian mosaic. to multiplied sameness; rather it presumes a This paper shows the complexities associated distinct difference in each instance" (Bannerji with understandings and interpretations of 2000, 41). In her discussions on Black women's identity and discusses Black women's question identity, Adrienne Shadd pointed to some of the of identity as situated in Black Canadian stereotypical questions that some racialized feminist theory. Canadians face and, particularly, the question Résumé of, "Where are they really from?" Shadd noted Le Canada est une nation qui encourage la that by asking this question, one is diversité et le multiculturalisme comme sa "unintentionally" denied what is rightfully pierre de coin pour bâtir un sentiment hers/his and at the same time rendered d’appartenance pour tous ses citoyens. -

Keynote Speaker Himani Bannerji, York University, Toronto

Society for Socialist Studies Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences 2-5 June 2015 University of Ottawa http://www.socialiststudies.ca Preliminary Program, 16 December 2014 Kapital Ideas: analysis, critique, praxis. Kapital Ideas are theories and analyses that help point us toward a better world through critique of the unequal, violent and exploitative one we now inhabit. They take inspiration from the author of Das Kapital, though they range widely over many issues which include ecology and political economy, gender and sexuality, colonization and imperialism, communication and popular struggles, but also movements and parties, hegemony and counter hegemony, governance and globalization and, of course, class struggle and transformation. Kapital Ideas are interventions that contribute to what Marx, in 1843, called the ‘self-clarification of the struggles and wishes of the age.’ In an era of deepening crisis and proliferating struggles, of grave threats and new possibilities, the need for these ideas, and for the praxis they can inform, could not be more acute. Keynote Speaker Himani Bannerji, York University, Toronto Marx’s critique of ideology: its uses and abuses The concept of ideology has been used in various contexts innumerable times and implied in even greater numbers. It has been both over-attended and under-attended in terms of its meaning, connotations and applications. This presentation is meant to examine some aspects of these uses, and what I consider its abuses, through an investigation of Marx’s own understanding and that of some of the Marxists. It will take into account a few well known theorists in the area, such as Lukacs and Althusser, Dorothy Smith and Raymond Williams, and its various uses in feminist theories. -

Marxism and Anti-Racism: a Contribution to the Dialogue

Marxism and Anti-Racism: A Contribution to the Dialogue Abigail B. Bakan Department of Political Studies Queen's University Kingston, Ontario A Paper Presented to the Annual General Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association and the Society for Socialist Studies York University Toronto, Ontario June, 2006 Draft only. Not for quotation without written permission from the author. 2 Introduction: The Need for a Dialogue The need for an extended dialogue between Marxism and anti-racism emerges from several points of entry. 1 It is motivated in part by a perceptible distance between these two bodies of thought, sometimes overt, sometimes more ambiguous. For example, Cedric J. Robinson, in his influential work, Black Marxism, stresses the inherent incompatibility of the two paradigms, though the title of his classic work suggests a contribution to a new synthesis. While emphasizing the historic divide, Robinson devotes considerable attention to the ground for commonality, including the formative role of Marxism in the anti-racist theories of authors and activists such as C.L.R. James and W. E. B. Dubois.2 In recent debates, anti-racist theorists such as Edward Said has rejected the general framework of Marxism, but are drawn to some Marxists such as Gramsci and Lukacs.3 There is also, however, a rich body of material that presumes a seamless integration between Marxism and anti-racism, including those such as Angela Davis, Eugene Genovese and Robin Blackburn.4 Identifying points of similarity and discordance between Marxism and anti-racism suggests the need for dialogue in order to achieve either some greater and more coherent synthesis, or, alternatively, to more clearly define the boundaries of distinct lines of inquiry. -

Women's Studies 5101

1 Women’s Studies 5101 – Winter 2016 Theories and Methods in Women’s Studies Dr. Lori Chambers 343-8218 RB 2016 [email protected] Feminism has fought no wars. It has killed no opponents. It has set up no concentration camps, starved no enemies, practiced no cruelties. Its battles have been for education, for the vote, for better working conditions . for safety on the streets . for child care, for social welfare . for rape crisis centers, women's refuges, reforms in the laws. If someone says ‘Oh, I'm not a feminist,’ I ask ‘Why? What’s your problem?” Dale Spender, For the Record: The Making and Meaning of Feminist Knowledge Course Description: The aim of the winter term is to provide an overview of the major themes and debates in feminist theory since the second wave, and to equip students to integrate feminist theory into a variety of disciplines. Required Readings: All students must purchase Sandra Kemp and Judith Squires, Feminisms from the university bookstore. Readings from this text are indicated below with page numbers only. Students must also purchase the course pack, also available at the bookstore. A number of articles are required, but not included in the course pack. This is because they are readily available through the online journal collections of the university. They are not reproduced in the course pack in order to save you money. Such articles are clearly indicated on the course outline below. Evaluation – this term is worth 50% of your overall grade: You may choose your own due dates and weighting (see options b.