Foreign Credentials in a Multicultural Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Access to Post-Secondary Education: Does Class Still Matter?

Access to Post-secondary Education: Does Class Still Matter? By Andrea Rounce ISBN: 0-88627-381-1 August 2004 CAW 567 ACCESS TO POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION: DOES CLASS STILL MATTER? By Andrea Rounce ISBN 0-88627-381-1 August 2004 About the author: Andrea Rounce is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Carlton University in Ottawa and a Research Associate for the Saskatchewan Office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives—Saskatchewan 2717 Wentz Avenue, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, S7K 4B6 Phone: (306) 978-5308, Fax: (306) 922-9162, email: [email protected] http:// www.policyalternatives.ca/sk Table of Contents Preamble . i Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Defining Access ..................................................................................................................... 1 Assessing Socio-Economic Status ....................................................................................... 3 Providing Context: The Current Post-Secondary Environment ........................................... 4 Making The Decision To Attend A Post-Secondary Institution ........................................... 8 Parental Expectations .......................................................................................................... 8 Knowledge of Costs and Funding Options ..................................................................... 9 Academic Achievement and Preparation -

Is Post-Secondary Access More Equitable in Canada Or the United States? by Marc Frenette

Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE — No. 244 ISSN: 1205-9153 ISBN: 0-662-39733-9 Research Paper Research Paper Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series Is Post-secondary Access More Equitable in Canada or the United States? by Marc Frenette Business and Labour Market Analysis Division 24-F, R.H. Coats Building, Ottawa, K1A 0T6 Telephone: 1 800 263-1136 Is Post-secondary Access More Equitable in Canada or the United States? by Marc Frenette 11F0019MIE No. 244 ISSN: 1205-9153 ISBN: 0-662-39733-9 Business and Labour Market Analysis 24 -F, R.H. Coats Building, Ottawa, ON K1A 0T6 Statistics Canada How to obtain more information : National inquiries line: 1 800 263-1136 E-Mail inquiries: [email protected] March 2005 This paper represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Statistics Canada. Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Minister of Industry, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission from Licence Services, Marketing Division, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0T6. Aussi disponible en français Table of Contents 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Literature review......................................................................................................................... -

Download Official Programme

The Society for Socialist Studies Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Canada June 4-6, 2019 The UBC Vancouver campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Circuits of Capital, Circles of Solidarity The circuits of financialised capitalism birthed by neoliberal capitalism have brought us to today’s historical moment of radical domestic and international inequality and with the existential threat of global warming. Much of the world is experiencing war and ongoing conflict, including genocide and apartheid, as new powers challenge the historic dominance of the West. Unnatural disasters threaten human and other life on planet Earth. A very small proportion of humanity holds most of the wealth and the world’s resources while others live in misery. There are new, bold expressions of old hatreds. Socialisms in all their variety matter today because they seek justice and peace for humanity, which is only possible through sustainable relationships with the natural world of which we are all a part. These struggles demand critical analyses of the unequal and ecologically destructive world we have inherited, as well as practices that prefigure a more just world to come in new circles of solidarity. For more than 50 years, the Society for Socialist Studies has endeavoured to open and maintain spaces for socialist and allied critical analyses and reflection, among both scholars and activists. -

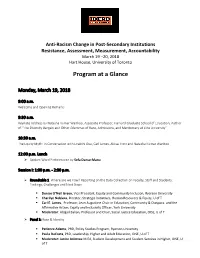

Program at a Glance

Anti-Racism Change in Post-Secondary Institutions Resistance, Assessment, Measurement, Accountability March 19 –20, 2018 Hart House, University of Toronto Program at a Glance Monday, March 19, 2018 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks 9:30 a.m. Keynote Address by Natasha Kumar Warikoo, Associate Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Author of “The Diversity Bargain and Other Dilemmas of Race, Admissions, and Meritocracy at Elite University” 10:30 a.m. The Equity Myth: In Conversation with Enakshi Dua, Carl James, Alissa Trotz and Natasha Kumar Warikoo 12:00 p.m. Lunch Spoken Word Performance by Sefa Danso-Manu Session I: 1:00 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. Roundtable 1: Where are we now? Reporting on the Data Collection on Faculty, Staff and Students: Findings, Challenges and Next Steps . Denise O’Neil Green, Vice President, Equity and Community Inclusion, Ryerson University . Cherilyn Nobleza, Director, Strategic Initiatives, Human Resources & Equity, U of T . Carl E. James, Professor, Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, and the Affirmative Action, Equity and Inclusivity Officer, York University . Moderator: Abigail Bakan, Professor and Chair, Social Justice Education, OISE, U of T Panel 1: Race & Identity . Patience Adamu, PhD, Policy Studies Program, Ryerson University . Paula DaCosta, PhD, Leadership, Higher and Adult Education, OISE, U of T . Moderator: Janice Asiimwe M.Ed, Student Development and Student Services in Higher, OISE, U of T Panel 2: Celebrating 10 years of the SOAR Indigenous Youth Gathering . Susan Lee, Assistant Director, Culture & Community, Rotman School of Management . Eleni Vlahiotis, MoveU and Equity Movement Coordinator, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, U of T . -

The Effect of Tax Subsidies to Employer-Provided Supplementary Health Insurance: Evidence from Canada

Journal of Public Economics 84 (2002) 305±339 www.elsevier.com/locate/econbase The effect of tax subsidies to employer-provided supplementary health insurance: evidence from Canada Amy Finkelstein* Department of Economics, MIT,50Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA Received 21 March 2000; received in revised form 17 September 2000; accepted 25 September 2000 Abstract This paper presents new evidence of the effect of the tax subsidy to employer-provided health insurance on coverage by such insurance. I study the effects of a 1993 tax change that reduced the tax subsidy to employer-provided supplementary health insurance in Quebec by almost 60%. Using a differences-in-differences methodology in which changes in Quebec are compared to changes in other provinces not affected by the tax change, I ®nd that this tax change was associated with a decrease of about one-®fth in coverage by employer-provided supplementary health insurance in Quebec. This corresponds to an elasticity of employer coverage with respect to the tax price of about 2 0.5. Non-group supplementary health insurance coverage rose slightly in Quebec relative to other provinces in response to the reduction in the tax subsidy to employer-provided (group) coverage. But the increase in the non-group market offset only 10±15% of the decrease in coverage through an employer. The decrease in coverage through an employer was especially pronounced in small ®rms, where the tax subsidy appears much more critical to the provision of supplementary health insurance than it does in larger ®rms. 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. -

Tuesday, June 8, 1999

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 240 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, June 8, 1999 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 15957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, June 8, 1999 The House met at 10 a.m. International Space Station and to make related amendments to other Acts. _______________ (Motions deemed adopted, bill read the first time and printed) Prayers * * * _______________ PETITIONS ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS CHILD PORNOGRAPHY Mr. Werner Schmidt (Kelowna, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, it is D (1005) indeed an honour and a privilege to present some 3,000-plus [Translation] petitioners who have come to the House with a petition. They would request that parliament take all measures necessary to GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS ensure that possession of child pornography remains a serious criminal offence, and that federal police forces be directed to give Mr. Peter Adams (Parliamentary Secretary to Leader of the priority to enforcing this law for the protection of our children. Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), I have the honour to table, in This is a wonderful petition and I endorse it 100%. both official languages, the government’s response to 10 petitions. THE CONSTITUTION * * * Mr. Svend J. Robinson (Burnaby—Douglas, NDP): Mr. [English] Speaker, I am presenting two petitions this morning. The first petition has been signed by residents of my constituency of COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE Burnaby—Douglas as well as communities across Canada. -

Nafta and the Environment

1 Introduction and Summary The United States, Canada, and Mexico share more than long borders; they also share guardianship of a common environmental heritage. At times they have worked together to deal with transborder problems such as air and water pollution and disposal of hazardous wastes. At other times, differences over resource management (especially water) have raised sovereignty concerns and provoked fractious disputes. As a result of a deepening integration over recent decades, particularly in urban clusters along the US-Canada and US-Mexico borders, environ- mental problems have become a highly charged regional issue. Whether it is the production of acid rain from industrial wastes, dumping of raw sewage, over-irrigation, or overuse of fertilizers, environmental policies and practices in each country are felt in its neighbors. Consistent time se- ries are not available, but the “made for TV” conditions in cities such as El Paso and Juárez, not to mention the Rio Grande river, suggest that en- vironmental conditions have worsened on the US-Mexico border over the past decade. Explosive growth has created new jobs and raised incomes, but it has been accompanied by more pollution. Worsening conditions in the midst of urban growth date back to the 1970s. Not surprisingly, the proposal a decade ago to advance regional integration by negotiating a North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) provoked sharp reaction by the environmental community. US environmental groups argued that increased industrial growth in Mexico, spurred by trade and investment reforms, would further damage Mex- ico’s environmental infrastructure; that lax enforcement of Mexican laws would encourage “environmental dumping”; and that increased compe- tition would provoke a “race to the bottom,” a weakening of environ- 1 Institute for International Economics | http://www.iie.com mental standards in all three countries. -

Marxism and Anti-Racism: a Contribution to the Dialogue

Marxism and Anti-Racism: A Contribution to the Dialogue Abigail B. Bakan Department of Political Studies Queen's University Kingston, Ontario A Paper Presented to the Annual General Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association and the Society for Socialist Studies York University Toronto, Ontario June, 2006 Draft only. Not for quotation without written permission from the author. 2 Introduction: The Need for a Dialogue The need for an extended dialogue between Marxism and anti-racism emerges from several points of entry. 1 It is motivated in part by a perceptible distance between these two bodies of thought, sometimes overt, sometimes more ambiguous. For example, Cedric J. Robinson, in his influential work, Black Marxism, stresses the inherent incompatibility of the two paradigms, though the title of his classic work suggests a contribution to a new synthesis. While emphasizing the historic divide, Robinson devotes considerable attention to the ground for commonality, including the formative role of Marxism in the anti-racist theories of authors and activists such as C.L.R. James and W. E. B. Dubois.2 In recent debates, anti-racist theorists such as Edward Said has rejected the general framework of Marxism, but are drawn to some Marxists such as Gramsci and Lukacs.3 There is also, however, a rich body of material that presumes a seamless integration between Marxism and anti-racism, including those such as Angela Davis, Eugene Genovese and Robin Blackburn.4 Identifying points of similarity and discordance between Marxism and anti-racism suggests the need for dialogue in order to achieve either some greater and more coherent synthesis, or, alternatively, to more clearly define the boundaries of distinct lines of inquiry. -

Nursing Leadership Development in Canada

Nursing Leadership Development in Canada A descriptive status report and analysis of leadership programs, approaches and strategies: domains and competencies; knowledge and skills; gaps and opportunities. Canadian Nurses Association Prepared for CNA by Dr. Heather Lee Kilty, Brock University Nursing Leadership Development in Canada © Copyright 2005 Canadian Nurses Association Canadian Nurses Association 50 Driveway Ottawa Ontario Canada K2P 1E2 www.cna-aiic.ca 1 Nursing Leadership Development in Canada Nursing Leadership Development in Canada A descriptive status report and analysis of leadership programs, approaches and strategies: domains and competencies; knowledge and skills; gaps and opportunities. Executive Summary Nursing leadership is alive and well, and evident in every nurse practising across the country and indeed around the world. The need for effective nursing and health care leadership has never been more critical for client care, health promotion, policy development and health care reform. The ongoing development of existing and emergent nurse leaders at this point in history is imperative. Nursing leadership encompasses a wide range of definitions, activities, frameworks, competencies and delivery mechanisms This report was produced to determine if current Canadian nursing leadership development programs are providing the skills and knowledge required for tomorrow's leaders. Internet searches, a review of published research and literature and key informant interviews were conducted with representatives and contact persons from relevant programs to gather information on existing leadership development approaches. Programs, experiences, courses, centres, projects, institutes and strategies (internationally and nationally; nursing and non-nursing) were reviewed. The key objectives of the report were to: 1. Examine key nursing leadership development programs in Canada. -

Homicide in Canada - 1999

Statistics Canada – Catalogue no. 85-002-XIE Vol. 20 no. 9 HOMICIDE IN CANADA - 1999 Orest Fedorowycz HIGHLIGHTS n The national homicide rate decreased by 4% in 1999, resulting in the lowest rate (1.76 per 100,000 population) since 1967. The rate has generally been decreasing since the mid-1970s. The 536 homicides in 1999 were 22 fewer than in 1998 and 16% lower than the average number for the previous ten years. n In general, homicide rates were higher in the west than in the east. British Columbia had the highest provincial rate in 1999, followed by Manitoba. Manitoba’s rate, however, was its lowest since 1967. The lowest rates were in Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island. n Only British Columbia, Ontario and New Brunswick reported increases in the number of homicides in 1999, although they all were lower than their previous ten-year averages. Saskatchewan dropped from 33 homicides in 1998 to 13 in 1999, resulting in the lowest homicide rate (1.26) since 1963. n Among the nine largest metropolitan areas, Vancouver reported the highest homicide rate, followed by Hamilton. Toronto had the lowest rate, followed by Calgary. Toronto’s rate was its lowest since CMA data were first tabulated in 1981. n Since 1976, firearms have accounted for about one-third of all homicides each year. This trend continued in 1999, with firearms being used in 31% of all homicides. The 165 shooting homicides in 1999 were up slightly from the 151 recorded in 1998, but much lower than the previous ten-year average of 205. -

The Appeal of Israel: Whiteness, Anti-Semitism, and the Roots of Diaspora Zionism in Canada

THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA by Corey Balsam A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Corey Balsam 2011 THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA Master of Arts 2011 Corey Balsam Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the appeal of Israel and Zionism for Ashkenazi Jews in Canada. The origins of Diaspora Zionism are examined using a genealogical methodology and analyzed through a bricolage of theoretical lenses including post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, and critical race theory. The active maintenance of Zionist hegemony in Canada is also explored through a discourse analysis of several Jewish-Zionist educational programs. The discursive practices of the Jewish National Fund and Taglit Birthright Israel are analyzed in light of some of the factors that have historically attracted Jews to Israel and Zionism. The desire to inhabit an alternative Jewish subject position in line with normative European ideals of whiteness is identified as a significant component of this attraction. It is nevertheless suggested that the appeal of Israel and Zionism is by no means immutable and that Jewish opposition to Zionism is likely to only increase in the coming years. ii Acknowledgements This thesis was not just written over the duration of my master’s degree. It is a product of several years of thinking and conversing with friends, family, and colleagues who have both inspired and challenged me to develop the ideas presented here. -

A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel Abigail F. Kolker The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2567 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE POTENCY OF POLICY?: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FILIPINO ELDER CARE WORKERS IN THE UNITED STATES AND ISRAEL by ABIGAIL F. KOLKER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Abigail F. Kolker All Rights Reserved ii The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F. Kolker This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ _____________________ Date Nancy Foner Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________ Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Richard Alba Philip Kasinitz Julia Wrigley THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Potency of Policy?: A Comparative Study of Filipino Elder Care Workers in the United States and Israel by Abigail F.