City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Luxo Na Moda Alta-Costura Entre O Passado E O Futuro

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Faculdade de Engenharia Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia Têxteis O Luxo na Moda Alta-Costura entre o passado e o futuro Rui André Melo de Sousa Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Design de Moda (2º ciclo de estudos) Orientador: Prof. Doutor Rui Alberto Lopes Miguel Coorientadora: Profª. Doutora Catarina Sofia Lourenço Rodrigues Covilhã, outubro de 2015 ii Agradecimentos Esta dissertação resulta de um esforço conjunto de profissionais e instituições, assim gostaria de expressar o meu profundo e sentido agradecimento a todos aqueles que contribuíram para a concretização desta dissertação. Agradeço em primeiro lugar aos meus orientadores, Professor Doutor Rui A. Lopes Miguel e Professora Doutora Catarina S. Lourenço Rodrigues por todo o apoio, esclarecimento e atenção disponibilizada. Gratifico ainda a Universidade da Beira Interior e o Departamento de Ciência e Engenharia Têxteis, pelas instalações, docentes e apoio recebido por parte de todos os funcionários do departamento que, com a experiência, ajudaram no meu crescimento profissional e pessoal. Muito especialmente, aos meus pais, por me terem proporcionado a oportunidade de ingressar no ensino superior e principalmente por toda a força e compreensão proporcionada. A minha avó, irmã e restante família por me terem ajudado direta ou indiretamente dando- me força, coragem e determinação. Aos meus amigos que me acompanharam durante a minha vida académica, à Catarina Marquês por ser uma irmã, à Rita Silva pelo sorriso incansável, à Rita Mendes pelas palavras, ao David Pinto pelo companheirismo, ao Hélio Cabrita pela amizade, à Michelle Reis por ser quem é, e a todos restantes com quem compartilhei bons momentos. -

Covid-19: Le New Black by Your Side

Covid-19: Le New Black by your side Much like every actor of the wholesale industry, we are monitoring the situation regarding Covid-19 pandemic as it evolves worldwide, and the initiatives arising to fight against it all over the world. We pay a huge tribute to these actions and support our clients during these difficult times. As a 100% Cloud platform, Le New Black naturally keeps on providing its entire range of services, without interruption or degradation, to support brands wholesale activity via web & mobile application and APIs. In order to guarantee the quality of our service and support brands during the crisis, the following measures have been taken: ● Protection of our team: our staff has been working from home since Monday March 16th when the government decreed confinement. Face-to-face meetings and trainings are being held remotely online or put on hold, and a close collaboration with our direct partners and suppliers has been set up to adapt to the crisis. Our entire staff will keep working from home from May 11th in compliance with government measures and meetings will remain online or put on hold. ● Client support mobilised: your account manager and the Customer Success team are available every day to answer any question you may have, and provide their advice regarding our features to support your activity (see contacts below). ● Community meet ups: this crisis aroused a deep need for talk, mutual aid and collaboration. With this in mind, Le New Black is now holding regular meetups where our community of brands is encouraged to share ideas, experiences and doubts raised by the crisis (learn more about community meet ups). -

The Effects of Globalization on the Fashion Industry– Maísa Benatti

ACKNOLEDGMENTS Thank you my dear parents for raising me in a way that I could travel the world and have experienced different cultures. My main motivation for this dissertation was my curiosity to understand personal and professional connections throughout the world and this curiosity was awakened because of your emotional and financial incentives on letting me live away from home since I was very young. Mae and Ingo, thank you for not measuring efforts for having me in Portugal. I know how hard it was but you´d never said no to anything I needed here. Having you both in my life makes everything so much easier. I love you more than I can ever explain. Pai, your time here in Portugal with me was very important for this masters, thank you so much for showing me that life is not a bed of roses and that I must put a lot of effort on the things to make them happen. I could sew my last collection because of you, your patience and your words saying “if it was easy, it wouldn´t be worth it”. Thank you to my family here in Portugal, Dona Teresinha, Sr. Eurico, Erica, Willian, Felipe, Daniel, Zuleica, Emanuel, Vitória and Artur, for understanding my absences in family gatherings because of the thesis and for always giving me support on anything I need. Dona Teresinha and Sr. Eurico, thank you a million times for helping me so much during this (not easy) year of my life. Thank you for receiving me at your house as if I were your child. -

FALL / WINTER 2017/2018 2017. Is It Fall and Winter?

THE FASHION GROUP FOUNDATION PRESENTS FALL / WINTER 2017/2018 TREND OVERVIEW BY MARYLOU LUTHER N E W Y O R K • LONDON • MILAN • PARIS DOLCE & GABBANA 2017. Is it Fall and Winter? Now and Next? Or a fluid season of see it/buy it and see it/wait for it? The key word is fluid, as in… Gender Fluid. As more women lead the same business lives as men, the more the clothes for those shared needs become less sex-specific. Raf Simons of Calvin Klein and Anna Sui showed men and women in identical outfits. For the first time, significant numbers of male models shared the runways with female models. Some designers showed menswear separately from women’s wear but sequentially at the same site. Transgender Fluid. Marc Jacobs and Proenza Schouler hired transgender models. Transsexuals also modeled in London, Milan and Paris. On the runways, diversity is the meme of the season. Model selections are more inclusive—not only gender fluid, but also age fluid, race fluid, size fluid, religion fluid. And Location Fluid. Philipp Plein leaves Milan for New York. Rodarte’s Kate and Laura Mulleavy leave New York for Paris. Tommy Hilfiger, Rebecca Minkoff and Rachel Comey leave New York for Los Angeles. Tom Ford returns to New York from London and Los Angeles. Given all this fluidity, you could say: This is Fashion’s Watershed Moment. The moment of Woman as Warrior—armed and ready for the battlefield. Woman in Control of Her Body—to reveal, as in the peekaboobs by Anthony Vaccarello for Yves Saint Laurent. -

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Umělecké Ztvárnění Těla

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra výtvarné výchovy Umělecké ztvárnění těla prostřednictvím oděvu Diplomová práce Brno 2017 Vedoucí práce: Autorka práce: PaedDr. Hana Stadlerová, Ph.D Bc. Markéta Kubátová BIBLIOGRAFICKÝ ZÁZNAM KUBÁTOVÁ, Markéta. Umělecké ztvárnění těla prostřednictvím oděvu. Doprovodný text k praktické diplomové práci. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, Katedra výtvarné výchovy, 2017. 93 l. 7 příl. Vedoucí bakalářské práce PaedDr. Hana Stadlerová, Ph.D. Rozsah textu diplomové práce je 63 normostran (116 262 znaků včetně mezer). ANOTACE Ústředním tématem diplomové práce Umělecké ztvárnění těla prostřednictvím oděvu je problematika znalosti lidského těla v módě. V teoretické části práce je nastíněn vývoj anatomických znalostí lidského těla ve výtvarném umění a módě haute couture. Práce rovněž mapuje tvorbu módních návrhářů, kteří se ve svých kolekcích opírají o znalosti lidského těla. Praktická část diplomové práce je realizace autorské oděvní kolekce, sestavené z deseti modelů inspirovaných lidskou kostrou. Ty jsou dále součástí edukačního programu s cílem představit studentům oděv jako jednu z forem umění, jež zprostředkovává lidské tělo, speciálně jeho kostru. KLÍČOVÁ SLOVA Oděv, kolekce, móda, haute couture, anatomie lidského těla, kostra. ANNOTATION The main topic of diploma thesis Artistic rendition of the body through the clothing is the issue of knowledge of the human body in fashion. The theoretical part outlines the development of anatomical knowledge of the human body in art and haute couture fashion. The thesis also presents work of fashion designers who based their fashion collections on knowledge of the human body. The practical part is the realization of the author's clothing collection, made up of ten models inspired by human skeleton. -

Bare Witness

are • THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART "This is a backless age and there is no single smarter sunburn gesture than to hm'c every low-backed cos tume cut on exactly the same lines, so that each one makes a perfect frame for a smooth brown back." British Vogue, July 1929 "iVladame du V. , a French lady, appeared in public in a dress entirely a Ia guil lotine. That is to say ... covered with a slight transparent gauze; the breasts entirely bare, as well as the arms up as high as the shoulders.... " Gemleman's A·1agazine, 1801 "Silk stockings made short skirts wearable." Fortune, January 1932 "In Defence ofSh** ld*rs" Punch, 1920s "Sweet hem·ting matches arc very often made up at these parties. It's quite disgusting to a modest eye to see the way the young ladies dress to attract the notice of the gentlemen. They are nearly naked to the waist, only just a little bit of dress hanging on the shoulder, the breasts are quite exposed except a little bit coming up to hide the nipples." \ Villiam Taylor, 1837 "The greatest provocation oflust comes from our apparel." Robert Burton, Anatomy ofi\Jelancholy, 1651 "The fashionable woman has long legs and aristocratic ankles but no knees. She has thin, veiled arms and fluttering hands but no elbows." Kennedy Fraser, The Fashionahlc 1VIind, 1981 "A lady's leg is a dangerous sight, in whatever colour it appears; but, when it is enclosed in white, it makes an irresistible attack upon us." The Unil'ersol !:lpectator, 1737 "'Miladi' very handsome woman, but she and all the women were dccollctees in a beastly fashion-damn the aristocratic standard of fashion; nothing will ever make me think it right or decent that I should see a lady's armpit flesh-folds when I am speaking to her." Georges Du ~ - laurier, 1862 "I would need the pen of Carlyle to describe adequately the sensa tion caused by the young lady who first tr.od the streets of New York in a skirt .. -

Al Via La Rivoluzione Con Kris Van Assche

il primo quotidiano della moda e del lusso Anno XXIX n. 066 - € 0,50 Direttore ed editore Caporedattore MFmercoledì fashion 4 aprile 2018 MF fashion Paolo Panerai - Stefano RoncatoI 04.04.18 ONLINE SU MFFASHION.COM LE GALLERY FOTOGRAFICHE DELLE COLLEZIONI F-W 2018/19 KRIS VAN ASSCHE KRIS VAN BBerlutierluti aall vviaia llaa rrivoluzioneivoluzione cconon KKrisris VVanan AAsschessche IIll ddesigneresigner bbelga,elga, eexx DDior,ior, è sstatotato nnominatoominato ddirettoreirettore ccreativoreativo ddii rreadyeady ttoo wwearear e aaccessoriccessori ddelel mmarchioarchio aall ppostoosto ddii HHaideraider AAckermann,ckermann, aandandondando a ccompletareompletare llaa nnuovauova ssquadraquadra ddelel mmenswearenswear ddelel ggrupporuppo ffranceserancese LLvmhvmh DDebutteràebutterà a PParigiarigi nnelel ggennaioennaio 22019019 rosegue il movimento dei direttori creativi all’interno del gruppo Lvmh, con un focus sul menswear. Il gruppo d’Oltralpe da 42,6 miliardi di euro di ricavi nel 2017 (+13%) ha annunciato che Kris PVan Assche sarà il nuovo designer di Berluti per il ready to wear, le calzature e gli accessori. Andrà a sostituire Haider Ackermann, la cui uscita è stata comunicata venerdì, e presenterà la sua prima collezione durante la settimana della moda di Parigi dedicata al menswear di genna- continua a pag. II BLACKSTAGE di Giampietro Baudo Ecce homo! Il menswear è morto? No, certamente no. Forse stan- la collezione homme Céline by Hedi Slimane. Ma tutta to, Craig Green, e sul debutto in pedana dell’uomo di no soffrendo le fashion week al maschile minori. Forse la stagione mannish sarà punteggiata da debutti eccel- Paul Surridge per Roberto Cavalli. Anche se le sorpre- sta soffrendo a livello di vendite retail. Sicuramente lenti e rilanci blasonati. -

TRANSLATION of the FRENCH “RAPPORT ANNUEL” AS of APRIL 30, 2013 Combined Shareholders’ Meeting October 18, 2013

TRANSLATION OF THE FRENCH “RAPPORT ANNUEL” AS OF APRIL 30, 2013 Combined Shareholders’ Meeting October 18, 2013 This document is a free translation into English of the original French “Rapport annuel”, hereafter referred to as the “Annual Report”. It is not a binding document. In the event of a conflict in interpretation, reference should be made to the French version, which is the authentic text. Chairman’s message 2 Parent company financial statements 183 Executive and Supervisory Bodies - Statutory Auditors 1. Balance sheet 184 as of April 30, 2013 4 2. Income statement 186 Simplified organizational chart of the Group 3. Cash flow statement 187 as of April 30, 2013 5 4. Notes to the parent company financial statements 188 Financial highlights 6 5. Subsidiaries and equity investments 196 6. Portfolio of subsidiaries and equity investments, Management report of the Board of Directors 7 other long-term and short-term investments 197 CHRISTIAN DIOR GROUP 7. Company results over the last five fiscal years 198 8. Statutory Auditors’ reports 199 1. Consolidated results 8 2. Results by business group 11 Resolutions for the approval of the Combined 3. Business risk factors and insurance policy 19 Shareholders’ Meeting of October 18, 2013 203 4. Financial policy 25 5. Stock option and bonus share plans 28 Ordinary resolutions 204 6. Exceptional events and litigation 29 Extraordinary resolution 206 7. Subsequent events 30 Statutory Auditors’ report on the proposed 8. Recent developments and prospects 30 decrease in share capital 207 CHRISTIAN DIOR PARENT COMPANY Other information 209 1. Results of Christian Dior 32 GOVERNANCE 2. -

Jeremy Renner Wears Dior Homme’S Wool Suit and Armani’S Cotton Shirt, Thom Browne’S Pocket Square

FALL 2010 / SPRING 2011 FirstWWD Look THEThe NEW SUITS: Magazine SLIM SHAPES, NEUTRAL PALETTE RAF SIMONS FROMHEADLINE AVANT-GARDE TO CENTER STAGE Super Manny EMANUELGOES CHIRICO’S GLOBALHERE VISION FOR CALVIN & TOMMY ZEGNA AT 100 PLUS RETROSEXUAL REVOLUTION MISTAKES MEN MAKE LUXURY REDEFINED JAPAN’S NEXT WAVE THE J. CREW FACTOR Display untilTHE XXXXXX LOOK 00, 2006 OF $10.00 WALL STREET DENIM ON THE BEACH JEREMYSPRING RENNER The Toast of the Town 0621.MW.001.Cover.a;23.indd 1 6/7/10 10:36:57 PM FABRIC N°1 A re-edition of the 1910 original, for the modern man AN ENDURING PASSION FOR FABRIC AND INNOVATION SINCE 1910 zegna.com FABRIC N°1 A re-edition of the 1910 original, for the modern man AN ENDURING PASSION FOR FABRIC AND INNOVATION SINCE 1910 zegna.com American Style. Ame rican Made. American Style. Ame rican Made. contents IN THE KNOW 15 People, places and things—talking points from the world of Menswear. RISING IN THE EAST Five Tokyo-based designers of the moment aim to build an international presence. 18 By Amanda Kaiser LET’S BE FRANK J. Crew’s Frank Muytjens has emerged as one of the most infl uential designers in 20 men’s fashion. By Jean E. Palmieri GREED LOOKS GOOD As Gordon Gekko resurfaces in the hedge fund era, Oliver Stone’s sequel tracks 22 the evolution of Wall Street style. By Brenner Thomas ON THE GRID 24 Highlights of fall culture and commerce. By Brenner Thomas MISTAKES MEN MAKE 26 The experts weigh in on the worst blunders in men’s fashion. -

Large Print Guide

Large Print Guide You can download this document from www.manchesterartgallery.org Sponsored by While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. Since its first issue in 1916, it has assumed a central role on the cultural stage with a history spanning the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. It has reflected events shaping the nation and Vogue 100: A Century of Style has been organised by the world, while setting the agenda for style and fashion. the National Portrait Gallery, London in collaboration with Tracing the work of era-defining photographers, models, British Vogue as part of the magazine’s centenary celebrations. writers and designers, this exhibition moves through time from the most recent versions of Vogue back to the beginning of it all... 24 June – 30 October Free entrance A free audio guide is available at: bit.ly/vogue100audio Entrance wall: The publication Vogue 100: A Century of Style and a selection ‘Mighty Aphrodite’ Kate Moss of Vogue inspired merchandise is available in the Gallery Shop by Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott, June 2012 on the ground floor. For Vogue’s Olympics issue, Versace’s body-sculpting superwoman suit demanded ‘an epic pose and a spotlight’. Archival C-type print Photography is not permitted in this exhibition Courtesy of Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott Introduction — 3 FILM ROOM THE FUTURE OF FASHION Alexa Chung Drawn from the following films: dir. Jim Demuth, September 2015 OUCH! THAT’S BIG Anna Ewers HEAT WAVE Damaris Goddrie and Frederikke Sofie dir. -

Fall 2019 Rizzoli Fall 2019

I SBN 978-0-8478-6740-0 9 780847 867400 FALL 2019 RIZZOLI FALL 2019 Smith Street Books FA19 cover INSIDE LEFT_FULL SIZE_REV Yeezy.qxp_Layout 1 2/27/19 3:25 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI Marie-Hélène de Taillac . .48 5D . .65 100 Dream Cars . .31 Minä Perhonen . .61 Achille Salvagni . .55 Missoni . .49 Adrian: Hollywood Designer . .37 Morphosis . .52 Aēsop . .39 Musings on Fashion & Style . .35 Alexander Ponomarev . .68 The New Elegance . .47 America’s Great Mountain Trails . .24 No Place Like Home . .21 Arakawa: Diagrams for the Imagination . .58 Nyoman Masriadi . .69 The Art of the Host . .17 On Style . .7 Ashley Longshore . .43 Parfums Schiaparelli . .36 Asian Bohemian Chic . .66 Pecans . .40 Bejeweled . .50 Persona . .22 The Bisazza Foundation . .64 Phoenix . .42 A Book Lover’s Guide to New York . .101 Pierre Yovanovitch . .53 Bricks and Brownstone . .20 Portraits of a Master’s Heart For a Silent Dreamland . .69 Broken Nature . .88 Renewing Tradition . .46 Bvlgari . .70 Richard Diebenkorn . .14 California Romantica . .20 Rick Owens Fashion . .8 Climbing Rock . .30 Rooms with a History . .16 Craig McDean: Manual . .18 Sailing America . .25 David Yarrow Photography . .5 Shio Kusaka . .59 Def Jam . .101 Skrebneski Documented . .36 The Dior Sessions . .50 Southern Hospitality at Home . .28 DJ Khaled . .9 The Style of Movement . .23 Eataly: All About Dolci . .40 Team Penske . .60 Eden Revisited . .56 Together Forever . .32 Elemental: The Interior Designs of Fiona Barratt Campbell .26 Travel with Me Forever . .38 English Gardens . .13 Ultimate Cars . .71 English House Style from the Archives of Country Life . -

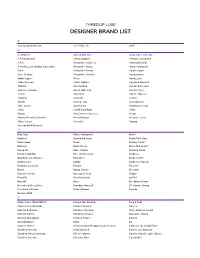

DesignerBrandList

THREDUP LUXE DESIGNER BRAND LIST # 10 Crosby Derek Lam 3.1 Phillip Lim 6397 A A Détacher Alessandra Rich Anna-Karin Karlsson A.F.Vandevorst Alexa Wagner Anthony Vaccarello A.P.C. Alexander McQueen Antonio Berardi A.W.A.K.E. by Natalia Alaverdian Alexander Wang Anya Hindmarch Acne Alexandre Birman Apiece Apart Acne Studios Alexandre Vauthier Aquascutum Adam Lippes Alexis Aquazzura Adam Selman Alexis Mabille Aquilano Rimondi ADEAM Alice McCall Armani Collezioni Adrienne Landau Alix of Bohemia Armani Prive Aether Altuzarra Arthur Arbesser Agnona Alumnae Ashish AKRIS Amelia Toro Atea Oceanie Akris punto Andrew Gn Atlantique Ascoli Alaïa André Courrèges Atlein Alanui Ann Demeulemeester Attico Alberta Ferretti Collection Anna October Au Jour Le Jour Albus Lumen Anna Sui Azzaro Alessandra Chamonix B Baja East Bibhu Mohapatra Brioni Baldinini Bionda Castana Brock Collection Balenciaga Biyan Brother Vellies Balmain Black Fleece Brunello Cucinelli Banjanan Blaze Milano Building Block Banjo & Matilda Bliss and Mischief Burberry Bao Bao Issey Miyake Blumarine Burberry Brit Barbara Bui Bodkin Burberry Prorsum Barbara Casasola Bogner Buscemi Barrie Borgo De Nor BUwood Barton Perreira Bottega Veneta Bvlgari Beaufille Bouchra Jarrar by FAR Belstaff Boyy By Malene Birger Benedetta Bruzziches Brandon Maxwell BY. Bonnie Young Bernhard Willhelm Brian Atwood Byredo Bertoni 1949 C Calvin Klein 205W39NYC Chanel Identification Cinq à Sept Calvin Klein Collection Charles Youssef Clare V. Camilla and Marc Charlotte Olympia Class Roberto Cavalli Camilla Elphick