I UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE the “Stylish Battle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Do We Really Suffer for Fashion

University of Huddersfield Repository Almond, Kevin You have to suffer for Fashion Original Citation Almond, Kevin (2009) You have to suffer for Fashion. In: Public Lecture University Centre Barnsley, July 2009, University Centre Barnsley. (Unpublished) This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/9663/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ You have to suffer for Fashion Introduction: ‘You have to suffer fashion,’ has been a much used phrase throughout the history of fashion. Degrees of suffering and discomfort have varied and we have probably all endured agonies, in some way, when constructing our appearance, in order to face the world. This could range from a simple cut from shaving, to the discomfort and pain of folding tender flesh into a girdle! These are only two, of numerous possible examples. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Fact Or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News

FACT OR FICTION: HOLLYWOOD LOOKS AT THE NEWS Loren Ghiglione Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University Joe Saltzman Director of the IJPC, associate dean, and professor of journalism USC Annenberg School for Communication Curators “Hollywood Looks at the News: the Image of the Journalist in Film and Television” exhibit Newseum, Washington D.C. 2005 “Listen to me. Print that story, you’re a dead man.” “It’s not just me anymore. You’d have to stop every newspaper in the country now and you’re not big enough for that job. People like you have tried it before with bullets, prison, censorship. As long as even one newspaper will print the truth, you’re finished.” “Hey, Hutcheson, that noise, what’s that racket?” “That’s the press, baby. The press. And there’s nothing you can do about it. Nothing.” Mobster threatening Hutcheson, managing editor of the Day and the editor’s response in Deadline U.S.A. (1952) “You left the camera and you went to help him…why didn’t you take the camera if you were going to be so humane?” “…because I can’t hold a camera and help somebody at the same time. “Yes, and by not having your camera, you lost footage that nobody else would have had. You see, you have to make a decision whether you are going to be part of the story or whether you’re going to be there to record the story.” Max Brackett, veteran television reporter, to neophyte producer-technician Laurie in Mad City (1997) An editor risks his life to expose crime and print the truth. -

Puvunestekn 2

1/23/19 Costume designers and Illustrations 1920-1940 Howard Greer (16 April 1896 –April 1974, Los Angeles w as a H ollywood fashion designer and a costume designer in the Golden Age of Amer ic an cinema. Costume design drawing for Marcella Daly by Howard Greer Mitc hell Leis en (October 6, 1898 – October 28, 1972) was an American director, art director, and costume designer. Travis Banton (August 18, 1894 – February 2, 1958) was the chief designer at Paramount Pictures. He is considered one of the most important Hollywood costume designers of the 1930s. Travis Banton may be best r emembered for He held a crucial role in the evolution of the Marlene Dietrich image, designing her costumes in a true for ging the s tyle of s uc h H ollyw ood icons creative collaboration with the actress. as Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae Wes t. Costume design drawing for The Thief of Bagdad by Mitchell Leisen 1 1/23/19 Travis Banton, Travis Banton, Claudette Colbert, Cleopatra, 1934. Walter Plunkett (June 5, 1902 in Oakland, California – March 8, 1982) was a prolific costume designer who worked on more than 150 projects throughout his career in the Hollywood film industry. Plunk ett's bes t-known work is featured in two films, Gone with the Wind and Singin' in the R ain, in which he lampooned his initial style of the Roaring Twenties. In 1951, Plunk ett s hared an Osc ar with Orr y-Kelly and Ir ene for An Amer ic an in Paris . Adr ian Adolph Greenberg ( 1903 —19 59 ), w i de l y known Edith H ead ( October 28, 1897 – October 24, as Adrian, was an American costume designer whose 1981) was an American costume designer mos t famous costumes were for The Wiz ard of Oz and who won eight Academy Awards, starting with other Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and The Heiress (1949) and ending with The Sting 1940s. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: an Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives Among Leathermen

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 5-2020 Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen University of Oklahoma, [email protected] Trenton M. Haltom University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Worthen, Meredith G. F. and Haltom, Trenton M., "Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen" (2020). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 707. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/707 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. digitalcommons.unl.edu Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen1 and Trenton M. Haltom2 1 University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; 2 University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA Corresponding author — Meredith G. F. Worthen, University of Oklahoma, 780 Van Vleet Oval, KH 331, Norman, OK 73019; [email protected] ORCID Meredith G. F. Worthen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6765-5149 Trenton M. Haltom http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1116-4644 Abstract The Fifty Shades books and films shed light on a sexual and leather-clad subculture predominantly kept in the dark: bondage, discipline, submission, and sadomasoch- ism (BDSM). -

Final J.Min |O.Phi |T.Cun |Editor |Copy

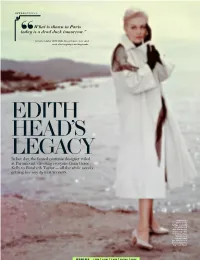

Style SPeCIAl What is shown in Paris today is a dead duck tomorrow.” — Costume designer EDITH HEAD, whose 57-year career owed “ much of its longevity to avoiding trends. C Edith Head’s LEgacy In her day, the famed costume designer ruled at Paramount, dressing everyone from Grace Kelly to Elizabeth Taylor — all the while savvily getting her way By Sam Wasson Kim Novak’s wardrobe for Vertigo, including this white coat with black scarf, was designed to look mysterious. “This girl must look as if she’s just drifted out of the San Francisco fog,” said Head. FINAL J.MIN |O.PHI |T.CUN |EDITOR |COPY Costume designer edith head — whose most unforgettable designs included Grace Kelly’s airy chiffon skirt in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, Gloria Swanson’s darkly elegant dresses in Sunset Boulevard, Dorothy Lamour’s sarongs, and Elizabeth Taylor’s white satin gown in A Place in the Sun — sur- vived 40 years of changing Hollywood styles by skillfully eschewing fads of the moment and, for the most part, gran- Cdeur and ornamentation, too. Boldness, she believed, was a vice. Thirty years after her death, Head is getting a new dose of attention. A gor- geous coffee table book,Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer, was recently published. And in late March, an A to Z adapta- tion of Head’s seminal 1959 book, The Dress Doctor, is being released as well. ! The sTyle setter of The screen The breezy volume spotlights her trade- Clockwise from above: 1. -

Official Announcement - January 26 - February 1 - 1941

Prairie View A&M University Digital Commons @PVAMU PV Week Academic Affairs Collections 1-26-1941 Official Announcement - January 26 - February 1 - 1941 Prairie View State College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-announcement Recommended Citation Prairie View State College, "Official Announcement - January 26 - February 1 - 1941" (1941). PV Week. 636. https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-announcement/636 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Affairs Collections at Digital Commons @PVAMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in PV Week by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @PVAMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ************************************************************* **************-<**¥*x***************************************** ******** PRAIRIE VIEW STATE COLLEGE ******** ******* ******* ****** "0L Q WEEKLY CALENDAR NO 17 ****** ******* ******* ******** January 26 - February 1, 1941 ******** ***********>.*-:<>,;****************************** **************** *************************** ************* *****************>.*** SUNDAY. JANUARY 26 9;00 A - Sunday School 11:00 A M - Morning Worship: PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY - College Chaplain 7:00 P M - Vesper - Faculty Debate - RESOLVED: THAT TEXAS SHOULD IN CREASE THE TAX ON NATURAL RESOURCES Affirmative Negative R W Hilliard J 0 Hopson H E Wright R A Smith Mrs M A Sanders Miss A L Sheffield Miss T. L Cunningham, Librarian Miss C Bradley, Librarian MONDAY. JANUARY 27 -

Will Connell Papers LSC.0893

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5199n9r9 Online items available Finding Aid for the Will Connell papers LSC.0893 Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 July 30. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Will Connell LSC.0893 1 papers LSC.0893 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Will Connell papers Creator: Connell, Will Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0893 Physical Description: 76 Linear Feet(152 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1928-1961 Abstract: Will Connell (1898-1961) was a self-taught photographer. He opened a studio in downtown Los Angeles in 1925 and became a member of the Camera Pictorialists. He taught at Art Center College in Pasadena from 1931 until his death. His work included movie publicity shots, magazine assignments and other commercial photography. The collection consists of photographs, negatives, experimental work, correspondence, instructional materials, and ephemera. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements PORTIONS OF THIS COLLECTION HAVE BEEN DIGITIZED. Please consult digital facsimiles instead of originals. Conditions Governing Use Property rights to the physical objects belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills.