1203 Settlement Patterns in the Southern Levant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25 April – 5 May 2019

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25th April – 5th May 2019 Trip Report author: Steve Arlow [email protected] Blog for further images: https://stevearlowsbirding.blogspot.com/ Purpose of this Trip Report / Guide I have visited Israel numerous times since spring since 2012 and have produced birding trip reports for each of those visits however for this report I have collated all of my previous useful information and detail, regardless if they were visited this year or not. Those sites not visited this time around are indicated within the following text. However, if you want to see the individual trip reports the below are detailed in Cloudbirders. March 2012 March 2013 April – May 2014 March 2016 April – May 2016 March 2017 April – May 2018 Summary of the Trip This year’s trip in late April into early May was not my first choice for dates, not even my second but it delivered on two key target species. Originally I had wanted to visit from mid-April to catch the Levant Sparrowhawk migration that I have missed so many previous times before however this coincided with Passover holidays in Israel and accommodation was either not available (Lotan) or bonkersly expensive (Eilat) plus the car rental prices were through the roof and there would be holiday makers everywhere. I decided then to return in March and planned to take in the Hula (for the Crane spectacle), Mt. Hermon, the Golan, the Beit She’an Valley, the Dead Sea, Arava and Negev as an all-rounder. However I had to cancel the day I was due to travel as an issue arose at home that I just had to be there for. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

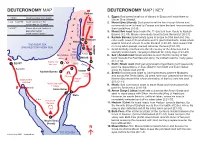

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

The Israel National Trail

Table of Contents The Israel National Trail ................................................................... 3 Preface ............................................................................................. 5 Dictionary & abbreviations ......................................................................................... 5 Get in shape first ...................................................................................................... 5 Water ...................................................................................................................... 6 Water used for irrigation ............................................................................................ 6 When to hike? .......................................................................................................... 6 When not to hike? ..................................................................................................... 6 How many kilometers (miles) to hike each day? ........................................................... 7 What is the direction of the hike? ................................................................................ 7 Hike and rest ........................................................................................................... 7 Insurance ................................................................................................................ 7 Weather .................................................................................................................. 8 National -

Israel Trail

Hillel Sussman he Israel Bike Trail is a national project for the construction of a mountain bike trail that traverses the entire country from the northernmost and highest point in Israel - TMount Hermon - to the lowest point on earth - the Dead Sea, and to the southernmost point - the city of Eilat on the shores of the Red Sea. Imagine that in just a few short years, you'll be able to hop on your bike on Mount Hermon and pedal away until you reach Eilat. The project is led by the Israel Nature Pedal your way to an appreciation of Israel’s landscapes and history and Parks Authority with financial support The Israel Bike Trail from the Ministry of Tourism and the Israel Government Tourist Corporation as well as other government ministries, including the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. The concept is that anyone who bikes the trail will learn about the diverse landscapes and cultures of Israel. In planning the trail, we have attempted to connect to as many important tourist sites as possible into a single contiguous trail. The trail is planned to extend over 1,200 kilometers (approximately 750 miles), making it one of the longest trails in the world, and perhaps the most beautiful and diverse. To create the trail, teams are currently deployed throughout Israel, seeking the best possible routes. The trail is being constructed with the highest possible mountain biking trail standards. Parts of it are being built by volunteers and others by professional trail builders. We set several principles for the planning phase: • Rider services - Each day begins and ends at a place where riders can sleep, eat and, if necessary, have their bikes repaired. -

ILH MAP 2014 Site Copy

Syria 99 a Mt.Hermon M 98 rail Odem Lebanon T O Rosh GOLAN HEIGHTS 98 Ha-Nikra IsraelNational 90 91 C Ha-Khula 899 Tel Hazor Akhziv Ma’alot Tarshiha 1 Nahariya 89 89 Katzrin More than a bed to sleep in! L. 4 3 888 12 Vered Hagalil 87 Clil Yehudiya Forest Acre E 85 5 4 Almagor 85 85 6 98 Inbar 90 Gamla 70 Karmiel Capernaum A 807 79 GALILEE 65 -212 meters 92 Givat Yoav R 13 -695 11 2 70 79 Zippori 8 7 75 Hilf Tabash 77 2 77 90 75 Nazareth 767 Khamat Israel’s Top 10 Nature Reserves & National Parks 70 9 Yardenit Gader -IS Mt. Carmel 10 Baptismal Site 4 Yoqneam Irbid Hermon National Park (Banias) - A basalt canyon hiking trail leading Nahal 60 S Me’arot to the largest waterfall in Israel. 70 Afula Zichron Ya’acov Megiddo 65 90 Yehudiya Forest Nature Reserve - Come hike these magnicent 71 trails that run along rivers, natural pools, and waterfalls. 60 Beit Alfa Jisr Az-Zarqa 14 6 Beit 65 Gan Shean Zippori National Park - A site oering impressive ruins and Caesarea Um El-Fahm Hashlosha Beit mosaics, including the stunning “Mona Lisa of the Galilee”. 2 Shean Jordan TEL Hadera 65 River Jenin Crossing Caesarea National Park - Explore the 3500-seat theatre and 6 585 S other remains from the Roman Empire at this enchanting port city. Jarash 4 Jerusalem Walls National Park - Tour this amazing park and view Biblical 60 90 Netanya Jerusalem from the city walls or go deep into the underground tunnels. -

Israel- Language and Culture.Pdf

Study Guide Israel: Country and Culture Introduction Israel is a republic on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea that borders Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. A Jewish nation among Arab and Christian neighbors, Israel is a cultural melting pot that reflects the many immigrants who founded it. Population: 8,002,300 people Capital: Jerusalem Languages: Hebrew and Arabic Flag of Israel Currency: Israeli New Sheckel History Long considered a homeland by various names—Canaan, Judea, Palestine, and Israel—for Jews, Arabs, and Christians, Great Britain was given control of the territory in 1922 to establish a national home for the Jewish people. Thousands of Jews immigrated there between 1920 and 1930 and laid the foundation for communities of cooperative villages known as “kibbutzim.” A kibbutz is a cooperative village or community, where all property is collectively owned and all members contribute labor to the group. Members work according to their capacity and receive food, clothing, housing, medical services, and other domestic services in exchange. Dining rooms, kitchens, and stores are central, and schools and children’s dormitories are communal. Assemblies elected by a vote of the membership govern each village, and the communal wealth of each village is earned through agricultural, entrepreneurial, or industrial means. The first kibbutz was founded on the bank of the Jordan River in 1909. This type of community was necessary for the early Jewish immigrants to Palestine. By living and working collectively, they were able to build homes and establish systems to irrigate and farm the barren desert land. At the beginning of the 1930s a large influx of Jewish immigrants came to Palestine from Germany because of the onset of World War II. -

Wild God in the Wilderness: Why Does Yahweh Choose to Appear in the Wilderness in the Book of Exodus?

WILD GOD IN THE WILDERNESS: WHY DOES YAHWEH CHOOSE TO APPEAR IN THE WILDERNESS IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS? by NARELLE JANE COETZEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT: The wilderness is an unlikely place for Yahweh to appear; yet some of the most profound encounters between Yahweh and ancient Israel occur in this isolated, barren, arid and marginal landscape. Thus, via John A. Beck’s narrative-geography method, which prioritises the role of the geographical setting of the biblical narrative, the question of ‘why does Yahweh choose to appear in the wilderness?’ is examined in reference to four Exodus theophanic passages (Exodus 3:1-4:17, 19:1-20:21, 24:9-18 and 33:18-34). First, a biblical working definition of the wilderness is developed, and the specific geographic elements in each passage discussed. Subsequently, the characterisation of Yahweh’s appearances is investigated, via the signs Yahweh used to appear, the words Yahweh speaks and the human experience of Yahweh in the wilderness space. -

403 Ancient Water Management in The

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 403-421 U. AVNER 403 ANCIENT WATER MANAGEMENT IN THE SOUTHERN NEGEV UZI AVNER INTRODUCTION The southern Negev is an extremely arid area, with summer temperatures above 400C, an average annual precipitation of 28 mm, and an annual potential evaporation rate of 4000 mm. This negative water balance causes the area to be poor in water sources and limits the Saharo-Arabian vegetation almost to- tally to wadi beds. Certainly, the desert presents several obstacles to the devel- opment of human communities, the foremost of which is the scarcity of water, for drinking, for everyday uses, for animals and for agriculture. Considering the environmental conditions, one would expect the Southern Negev to be al- most devoid of ancient remains of human presence and activity. However, the harshest part of this area, from ‘Uvda Valley and southward (see Map 1), is surprisingly rich in archaeological sites. A complete sequence of settlement is found during the last 10,000 years, with a wide range of activi- ties such as hunting, grazing, agriculture, trade, copper production, some gold production and others (Avner et al 1994). In this article I will describe several methods of water exploitation in the region. The first will concern the early agricultural settlement in ‘Uvda Valley, 6th to 3rd millennia B.C., the others relate to the Nabatean and the Early Islamic period. AGRICULTURAL SETTLEMENT IN ‘UVDA VALLEY ‘Uvda Valley (Wadi ‘Uqfi in Arabic), 40 km north of the Gulf of Aqaba (Fig. 1), was first briefly described by A. Musil (1907:180-182, 1926:85). -

BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN the Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University

BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN The Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University ISSN 1938-694X Volume VII Number 8 The Jordan River Valley, the Jordan River and the Jungle of the Jordan Gary A. Byers Abstract: This brief popular article provides a description of the southern Jordan Valley as a background for the excavation at Tall el-Hammam on the eastern Jordan Disk. It has previously appeared in several publications, and is republished here with permission from the author. © Copyright 2007, Trinity Southwest University Special copyright, publication, and/or citation information: Biblical Research Bulletin is copyrighted by Trinity Southwest University. All rights reserved. Article content remains the intellectual property of the author. This article may be reproduced, copied, and distributed, as long as the following conditions are met: 1. If transmitted electronically, this article must be in its original, complete PDF file form. The PDF file may not be edited in any way, including the file name. 2. If printed copies of all or a portion of this article are made for distribution, the copies must include complete and unmodified copies of the article’s cover page (i.e., this page). 3. Copies of this article may not be charged for, except for nominal reproduction costs. 4. Copies of this article may not be combined or consolidated into a larger work in any format on any media, without the written permission of Trinity Southwest University. Brief quotations appearing in reviews and other works may be made, so long as appropriate credit is given and/or source citation is made. For submission requirements visit www.BiblicalResearchBulletin.com.