BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN the Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”............................................................................. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

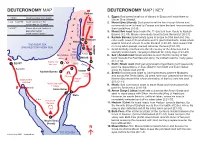

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

Water, Ecology, and the Jordan River in Islam

RIVER OUT OF EDEN: WATER, ECOLOGY, AND THE JORDAN RIVER IN ISLAM ECOPEACE / FRIENDS OF THE EARTH MIDDLE EAST (FOEME) SECOND EDITION, JUNE 2014 © Jos Van Wunnik COVENANT FOR THE JORDAN RIVER We recognize that the Jordan River Valley is that cripples the growth of an economy a landscape of outstanding ecological and based on tourism, and that exacerbates the cultural importance. It connects the eco- political conflicts that divide this region. It systems of Africa and Asia, forms a sanctuary also exemplifies a wider failure to serve as for wild plants and animals, and has witnessed custodians of the planet: if we cannot protect a some of the most significant advances in place of such exceptional value, what part of the human history. The first people ever to leave earth will we hand on intact to our children? Africa walked through this valley and drank from its springs. Farming developed on these We have a different vision of this valley: a vision plains, and in Jericho we see the origins of in which a clean, living river flows from the Sea urban civilization itself. Not least, the river runs of Galilee to the Dead Sea; in which the valley’s through the heart of our spiritual traditions: plants and animals are afforded the water they some of the founding stories of Judaism, need to flourish; in which the springs flow as Christianity, and Islam are set along its banks they have for millennia; and in which the water and the valley contains sites sacred to half extracted for human use is divided equitably of humanity. -

February 7, 2021 Jordan $4,965

Bethlehem Sea of Galilee Nazareth HOLY LAND HERITAGE & Jordan Jerusalem January 25 – February 7, 2021 Jordan $4,965. *DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Single Supplement Add $680 Inclusions: R/T Air - Fargo/Bismarck - Subject to change Hotel List: Leonardo Plaza– Netanya • 4 Star Accommodations Maagan - Tiberias • Baggage Handling at Hotel Ambassador – Jerusalem • 21 Included Meals Petra Guest House – Petra • Caesarea Maritima * Plain of Jezreel Dead Sea Spa Hotel – Dead • Nazareth * Sea of Galilee Sea • Beth Saida * Capernaum * Chorazin • Jordan River * Jordan Valley • Caesarea Philippi * Golan Heights • Beth Shean * Ein Harod * Jericho • Mt. of Olives * Rachael’s Tomb For Reservations Contact: • Bethlehem * Dead Sea Scrolls JUDY’S LEISURE TOURS • Jerusalem * Bethany * Masada *Passport is required • Dung Gate * Western Wall Valid for 6 months 4906 16 STREET N • Pools of Bethesda * St. Anne’s Church beyond travel date. Fargo, ND 58102 • King David’s Tomb • Mt. Zion * Garden Tomb 701/232-3441 or • Jordan * Petra * Seir Mountains • Royal Tombs * Historical King’s Highway 800/598-0851 • Madaba * Mt Nebo • Baptismal Site “Bethany beyond the Jordan” Insurance $382. Purchase at time of Deposit Day 1 & 2: We will depart the United States for overnight travel to Israel. After clearing customs, we will be met by our guide who will take us on a scenic drive through Jaffa, the oldest port in the world. Jonah set sail for Tarshish from Jaffa but was swallowed by a large fish. Jaffa was also the home of Tabitha, who was raised from the dead by Peter. Peter had his vision here while lodging in the home of Simon the Tanner. -

Where Jesus Walked

Where Jesus Walked: Day 01: Arrival at QAIA – Meet & Assist – Transfer Amman for 4 Nights You will arrive at Amman airport and will be met by our representative at the airport; you will transfer to your hotel in Amman where you will spend 4 nights Day 02: Visit Bethany – Visit Churches in Amman & King Abdullah Mosque You will be collected form your hotel after breakfast and travel to Bethany Beyond Jordan, which is located very close to the Lowest Place on Earth the Dead Sea. For Christians Bethany Beyond Jordan is probably the most significant pilgrim site in the world. Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan River, the opening of the heavens and the arrival of the Holy Spirit is the very beginning of Christianity. John was baptizing in the river Jordan close to Beit 'Abara, where Joshua, Elijah and Elisha crossed the river and very close to where Elijah ascended into heaven. In New Testament times, it became known as Bethany, the village of John the Baptist. This Bethany is not to be confused with the village of Bethany near Jerusalem, where the Bible says Lazarus was raised from the dead. The Bible clearly records that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist (Matthew 3: 13-17), and that John the Baptist lived, preached and baptized in the village of Bethany, on "the other side of the Jordan" (John 1: 28). The baptism site, known in Arabic as al- Maghtas, is located at the head of a lush valley just east of the Jordan River. After Jesus' baptism at Bethany, he spent forty days in the wilderness east of the River Jordan, where he fasted and resisted the temptations of Satan (Mark 1: 13, Matthew 4: 1-11). -

Israel- Language and Culture.Pdf

Study Guide Israel: Country and Culture Introduction Israel is a republic on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea that borders Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. A Jewish nation among Arab and Christian neighbors, Israel is a cultural melting pot that reflects the many immigrants who founded it. Population: 8,002,300 people Capital: Jerusalem Languages: Hebrew and Arabic Flag of Israel Currency: Israeli New Sheckel History Long considered a homeland by various names—Canaan, Judea, Palestine, and Israel—for Jews, Arabs, and Christians, Great Britain was given control of the territory in 1922 to establish a national home for the Jewish people. Thousands of Jews immigrated there between 1920 and 1930 and laid the foundation for communities of cooperative villages known as “kibbutzim.” A kibbutz is a cooperative village or community, where all property is collectively owned and all members contribute labor to the group. Members work according to their capacity and receive food, clothing, housing, medical services, and other domestic services in exchange. Dining rooms, kitchens, and stores are central, and schools and children’s dormitories are communal. Assemblies elected by a vote of the membership govern each village, and the communal wealth of each village is earned through agricultural, entrepreneurial, or industrial means. The first kibbutz was founded on the bank of the Jordan River in 1909. This type of community was necessary for the early Jewish immigrants to Palestine. By living and working collectively, they were able to build homes and establish systems to irrigate and farm the barren desert land. At the beginning of the 1930s a large influx of Jewish immigrants came to Palestine from Germany because of the onset of World War II. -

Today's Bible Story Is About Crossing the Jordan River and Conquering Jericho

The Story (7.5): The Battle Begins 08/29/2021 Joshua 6:2-5 Rev. Dr. Sunny Ahn Today's Bible story is about crossing the Jordan River and conquering Jericho. After 40 years of the honeymoon in the wilderness, God and God's people are about to move into their new home in the Promised Land—Canaan. This moving is not gonna be an easy one for God's people as they face a wall of the Jordan River, a land of warriors, and powerful cities on the way. So, God prepares them, starting with their new leader and God's new partner, Joshua, by strengthening his heart, mind, and soul with a commend, "Be strong and very courageous." Now, it is the time for Joshua and God's people to put their faith in action for crossing the Jordan River and conquering Jericho. Crossing the Jordan River was one of the key events in Israel's history. Just as God brought God's people out of the land of bondage by dividing the Red Sea, so God brings them into the Promised Land by dividing the Jordan River. No armies were chasing Israel this time as in Egypt. They could have built boats and taken their time to cross the Jordan River, but God led them by dividing the Jordan River for three reasons: First, to put His confirmation on Joshua as Moses' authorized successor. He says in Joshua 3:7, "This day I will begin to exalt you in the sight of all Israel, that they may know that, as I was with Moses, so I will be with you." Second, God aimed to strengthen the people's faith that He is with them and will give them victory in the battles ahead (Joshua 3:10). -

Teacher Bible Study Lesson Overview

4th-6th Grade Kids Bible Study Guide Unit 8, Session 1: The Israelites Crossed the Jordan River TEACHER BIBLE STUDY Only one geographical barrier separated the Israelites from the promised land of Canaan: the Jordan River. When Joshua and the Israelites arrived, the Jordan River was flooded due to spring rains and snowmelt. Any other time, the river would have been manageable, but crossing the swollen river would have been as daunting as crossing the Red Sea. (See Joshua 4:23.) God gave Joshua a promise and a command. First, He promised to drive out from before them all the people of the land. Then God told him to tell the priests to carry the ark of the LORD (a symbol of God’s powerful presence) into the waters of the Jordan. Then the waters of the river would be cut off from flowing, and the waters coming down from above would stand in one heap. The priests did as Joshua commanded. The waters stopped, and all of the people passed over on dry ground. The LORD commanded Joshua to have 12 men each take a stone from the middle of the Jordan. When the priests came up out of the river, the water started to flow and was again flooded. Joshua set up the stones to be a memorial. The stones served as a reminder of God’s faithfulness in bringing Israel safely across the Jordan into the promised land. The Israelites could do nothing apart from God. He was with them, and He was going to fight for them. -

Wild God in the Wilderness: Why Does Yahweh Choose to Appear in the Wilderness in the Book of Exodus?

WILD GOD IN THE WILDERNESS: WHY DOES YAHWEH CHOOSE TO APPEAR IN THE WILDERNESS IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS? by NARELLE JANE COETZEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT: The wilderness is an unlikely place for Yahweh to appear; yet some of the most profound encounters between Yahweh and ancient Israel occur in this isolated, barren, arid and marginal landscape. Thus, via John A. Beck’s narrative-geography method, which prioritises the role of the geographical setting of the biblical narrative, the question of ‘why does Yahweh choose to appear in the wilderness?’ is examined in reference to four Exodus theophanic passages (Exodus 3:1-4:17, 19:1-20:21, 24:9-18 and 33:18-34). First, a biblical working definition of the wilderness is developed, and the specific geographic elements in each passage discussed. Subsequently, the characterisation of Yahweh’s appearances is investigated, via the signs Yahweh used to appear, the words Yahweh speaks and the human experience of Yahweh in the wilderness space.