In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

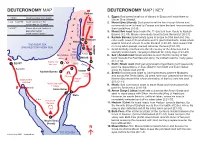

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

The Jewish Federations of North America Urges Caution And

Volume XIV Issue 4 Iyar/Sivan 5775 May 2015 The Jewish Federations of North America Urges Caution and Congressional Review of Any Iran Deal April 2, 2015 The Administration has repeatedly reaffirmed that “it is unacceptable for Iran to have a nuclear weapon.” Even during the current negotiations, the White House has often said, “a bad deal is worse than no deal.” We appreciate the good faith efforts made by the Admin- istration and the other members of the P5+1. We all hope that a diplomatic solution to stop Iran from acquiring a View photos of the community Yom HaShoah nuclear weapon is possible. Commemoration on pages 16-17. However, the framework presented today leaves vital is- sues woefully unresolved. The agreement provides scant detail on how the phased sanction relief will be imple- CAMPAIGN NEWS mented. It contains insufficient clarity on how Iranian Major Gifts Brunch to be held on May 17 adherence to the agreement will be verified. And it is The Major Gifts Champagne Brunch will be held on Sun- ambiguous on what penalties will be imposed if Iran fails day, May 17 at 11:00 a.m. at the home of Linda and Leon to fulfill its commitments. Ravvin. The guest speakers will be Jeff Polson and Tif- fany Fabing, Executive Director and Board Coordinator of A weak agreement presents a clear and present danger to the Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence. all nations. It is also likely to lead other countries in the With financial assets exceeding $100 million, the Jew- region to seek their own nuclear capabilities, resulting in ish Heritage Fund for Excellence (JHFE) is committed to a proliferation of nuclear weapons in a part of the world improving health and fostering a vibrant Jewish Commu- already destabilized by Iranian proxies spreading terror- nity in Metropolitan Louisville and the Commonwealth of ism and fomenting extremism. -

Renewable Energy As a Catalyst For

Renewable Energy as a Catalyst for Regional Development The Arava Center for Sustainable Development at the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Israel November 18th through November 30th, 2012 Program Introduction Energy is crucial for economic growth and social progress. Achieving sustainable growth requires solutions to today’s environmental problems call for long-term actions for sustainable development. In this regard, renewable energy resources appear to be one of the most efficient and effective solutions. The use of renewable and clean energy is increasing and will be the effective and practical choice to guarantee future global development. Renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, biomass and geothermal can offer solutions for various problems that challenge the development of many regions around the world. The vital role and the potential of renewable energy in regional development have been globally recognized, however, its widespread implementation is not progressing as rapidly as is needed. This training program, to be held at the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies (AIES), located on Kibbutz Ketura in the south of Israel, provides an opportunity for mid-level professionals from the public sector to gain knowledge about the basics of renewable energies and how to use renewable energy sources as a catalyst for regional development. The primary topics include the principles of renewable energy, the present, past and future of energy consumption, the pros and cons of renewable energy, energy production and costs, energy conversion, energy assessments, fossil fuels, regulations, environmental issues and the social and cultural impact of renewable energy. The training program will utilize the extensive knowledge of the Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation (CREEC) at AIES and the Eilat-Eilot Renewable Energy Initiative. -

Israel- Language and Culture.Pdf

Study Guide Israel: Country and Culture Introduction Israel is a republic on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea that borders Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. A Jewish nation among Arab and Christian neighbors, Israel is a cultural melting pot that reflects the many immigrants who founded it. Population: 8,002,300 people Capital: Jerusalem Languages: Hebrew and Arabic Flag of Israel Currency: Israeli New Sheckel History Long considered a homeland by various names—Canaan, Judea, Palestine, and Israel—for Jews, Arabs, and Christians, Great Britain was given control of the territory in 1922 to establish a national home for the Jewish people. Thousands of Jews immigrated there between 1920 and 1930 and laid the foundation for communities of cooperative villages known as “kibbutzim.” A kibbutz is a cooperative village or community, where all property is collectively owned and all members contribute labor to the group. Members work according to their capacity and receive food, clothing, housing, medical services, and other domestic services in exchange. Dining rooms, kitchens, and stores are central, and schools and children’s dormitories are communal. Assemblies elected by a vote of the membership govern each village, and the communal wealth of each village is earned through agricultural, entrepreneurial, or industrial means. The first kibbutz was founded on the bank of the Jordan River in 1909. This type of community was necessary for the early Jewish immigrants to Palestine. By living and working collectively, they were able to build homes and establish systems to irrigate and farm the barren desert land. At the beginning of the 1930s a large influx of Jewish immigrants came to Palestine from Germany because of the onset of World War II. -

Wild God in the Wilderness: Why Does Yahweh Choose to Appear in the Wilderness in the Book of Exodus?

WILD GOD IN THE WILDERNESS: WHY DOES YAHWEH CHOOSE TO APPEAR IN THE WILDERNESS IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS? by NARELLE JANE COETZEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT: The wilderness is an unlikely place for Yahweh to appear; yet some of the most profound encounters between Yahweh and ancient Israel occur in this isolated, barren, arid and marginal landscape. Thus, via John A. Beck’s narrative-geography method, which prioritises the role of the geographical setting of the biblical narrative, the question of ‘why does Yahweh choose to appear in the wilderness?’ is examined in reference to four Exodus theophanic passages (Exodus 3:1-4:17, 19:1-20:21, 24:9-18 and 33:18-34). First, a biblical working definition of the wilderness is developed, and the specific geographic elements in each passage discussed. Subsequently, the characterisation of Yahweh’s appearances is investigated, via the signs Yahweh used to appear, the words Yahweh speaks and the human experience of Yahweh in the wilderness space. -

403 Ancient Water Management in The

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 403-421 U. AVNER 403 ANCIENT WATER MANAGEMENT IN THE SOUTHERN NEGEV UZI AVNER INTRODUCTION The southern Negev is an extremely arid area, with summer temperatures above 400C, an average annual precipitation of 28 mm, and an annual potential evaporation rate of 4000 mm. This negative water balance causes the area to be poor in water sources and limits the Saharo-Arabian vegetation almost to- tally to wadi beds. Certainly, the desert presents several obstacles to the devel- opment of human communities, the foremost of which is the scarcity of water, for drinking, for everyday uses, for animals and for agriculture. Considering the environmental conditions, one would expect the Southern Negev to be al- most devoid of ancient remains of human presence and activity. However, the harshest part of this area, from ‘Uvda Valley and southward (see Map 1), is surprisingly rich in archaeological sites. A complete sequence of settlement is found during the last 10,000 years, with a wide range of activi- ties such as hunting, grazing, agriculture, trade, copper production, some gold production and others (Avner et al 1994). In this article I will describe several methods of water exploitation in the region. The first will concern the early agricultural settlement in ‘Uvda Valley, 6th to 3rd millennia B.C., the others relate to the Nabatean and the Early Islamic period. AGRICULTURAL SETTLEMENT IN ‘UVDA VALLEY ‘Uvda Valley (Wadi ‘Uqfi in Arabic), 40 km north of the Gulf of Aqaba (Fig. 1), was first briefly described by A. Musil (1907:180-182, 1926:85). -

BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN the Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University

BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN The Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University ISSN 1938-694X Volume VII Number 8 The Jordan River Valley, the Jordan River and the Jungle of the Jordan Gary A. Byers Abstract: This brief popular article provides a description of the southern Jordan Valley as a background for the excavation at Tall el-Hammam on the eastern Jordan Disk. It has previously appeared in several publications, and is republished here with permission from the author. © Copyright 2007, Trinity Southwest University Special copyright, publication, and/or citation information: Biblical Research Bulletin is copyrighted by Trinity Southwest University. All rights reserved. Article content remains the intellectual property of the author. This article may be reproduced, copied, and distributed, as long as the following conditions are met: 1. If transmitted electronically, this article must be in its original, complete PDF file form. The PDF file may not be edited in any way, including the file name. 2. If printed copies of all or a portion of this article are made for distribution, the copies must include complete and unmodified copies of the article’s cover page (i.e., this page). 3. Copies of this article may not be charged for, except for nominal reproduction costs. 4. Copies of this article may not be combined or consolidated into a larger work in any format on any media, without the written permission of Trinity Southwest University. Brief quotations appearing in reviews and other works may be made, so long as appropriate credit is given and/or source citation is made. For submission requirements visit www.BiblicalResearchBulletin.com. -

Israel 2019 Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments are due to representatives of government ministries and agencies as well as many others from a variety of organizations, for their essential contributions to each chapter of this book. Many of these bodies are specifically cited within the relevant parts of this report. The inter-ministerial task force under the guidance of Ambassador Yacov Hadas-Handelsman, Israel’s Special Envoy for Sustainability and Climate Change of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Galit Cohen, Senior Deputy Director General for Planning, Policy and Strategy of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, provided invaluable input and support throughout the process. Special thanks are due to Tzruya Calvão Chebach of Mentes Visíveis, Beth-Eden Kite of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Amit Yagur-Kroll of the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Ayelet Rosen of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Shoshana Gabbay for compiling and editing this report and to Ziv Rotshtein of the Ministry of Environmental Protection for editorial assistance. 3 FOREWORD The international community is at a crossroads of countries. Moreover, our experience in overcoming historical proportions. The world is experiencing resource scarcity is becoming more relevant to an extreme challenges, not only climate change, but ever-increasing circle of climate change affected many social and economic upheavals to which only areas of the world. Our cooperation with countries ambitious and concerted efforts by all countries worldwide is given broad expression in our VNR, can provide appropriate responses. The vision is much of it carried out by Israel’s International clear. -

Arvot Newsmagazıne Central Arava Regional Council Issue 2 December 2009

The Central Arava Regional Council Journal Arvot Newsmagazıne Central Arava Regional Council Issue 2 December 2009 Central & Northern Arava R&D Arava Open Day 2010 and more Page 8 Water Brings life to the desert Page 10 Limmud Arava Page 12 Editor’s Column Six months have passed from new residents to the area - our first issue and I would like a fact that is critical. While to thank all the readers who the Central Arava comprises sent feedback. It was great 6% of the area of the land of to receive such constructive Israel, it has only 0.06% of the comments about the articles population - 3,000 residents, in general and, in particular, and is known as the most the decision to publish a peripheral area from urban newspaper in English. centers in Israel. A lot has happened during the I hope the articles will be of last 6 months in the Central interest and should you wish Arava. This magnificent area any further information or have that was established decades any comments please feel free ago by some “crazy” young to contact me directly. We especially would like to pioneers is on the verge of a We would like to take this thank: breaking point of development opportunity to thank our in all areas. As you will read supporters who have made • JNF USA in the articles, the Council is our programs in the Arava • JNF Charitable Trust (UK) developing major projects possible. Without them we • Jewish National Fund of in Education, Culture, Water wouldn’t be able to initiate Australia and Sustainable Environment, and execute such important • Jewish National Fund of Health and Senior Citizens etc.