Wilderness of Zin”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAU Archaeology the Jacob M

TAU Archaeology The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities | Tel Aviv University Number 4 | Summer 2018 Golden Jubilee Edition 1968–2018 TAU Archaeology Newsletter of The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities Number 4 | Summer 2018 Editor: Alexandra Wrathall Graphics: Noa Evron Board: Oded Lipschits Ran Barkai Ido Koch Nirit Kedem Contact the editors and editorial board: [email protected] Discover more: Institute: archaeology.tau.ac.il Department: archaeo.tau.ac.il Cover Image: Professor Yohanan Aharoni teaching Tel Aviv University students in the field, during the 1969 season of the Tel Beer-sheba Expedition. (Courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University). Photo retouched by Sasha Flit and Yonatan Kedem. ISSN: 2521-0971 | EISSN: 252-098X Contents Message from the Chair of the Department and the Director of the Institute 2 Fieldwork 3 Tel Shimron, 2017 | Megan Sauter, Daniel M. Master, and Mario A.S. Martin 4 Excavation on the Western Slopes of the City of David (‘Giv’ati’), 2018 | Yuval Gadot and Yiftah Shalev 5 Exploring the Medieval Landscape of Khirbet Beit Mamzil, Jerusalem, 2018 | Omer Ze'evi, Yelena Elgart-Sharon, and Yuval Gadot 6 Central Timna Valley Excavations, 2018 | Erez Ben-Yosef and Benjamin -

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Parshat Matot/Masei

Parshat Matot/Masei A free excerpt from the Kehot Publication Society's Chumash Bemidbar/Book of Numbers with commentary based on the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, produced by Chabad of California. The full volume is available for purchase at www.kehot.com. For personal use only. All rights reserved. The right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, requires permission in writing from Chabad of California, Inc. THE TORAH - CHUMASH BEMIDBAR WITH AN INTERPOLATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY BASED ON THE WORKS OF THE LUBAVITCHER REBBE Copyright © 2006-2009 by Chabad of California THE TORAHSecond,- revisedCHUMASH printingB 2009EMIDBAR WITH AN INTERPOLATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARYA BprojectASED ON of THE WORKS OF ChabadTHE LUBAVITCH of CaliforniaREBBE 741 Gayley Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 310-208-7511Copyright / Fax © 310-208-58112004 by ChabadPublished of California, by Inc. Kehot Publication Society 770 Eastern Parkway,Published Brooklyn, by New York 11213 Kehot718-774-4000 Publication / Fax 718-774-2718 Society 770 Eastern Parkway,[email protected] Brooklyn, New York 11213 718-774-4000 / Fax 718-774-2718 Order Department: 291 KingstonOrder Avenue, Department: Brooklyn, New York 11213 291 Kingston718-778-0226 Avenue / /Brooklyn, Fax 718-778-4148 New York 11213 718-778-0226www.kehot.com / Fax 718-778-4148 www.kehotonline.com All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book All rightsor portions reserved, thereof, including in any the form, right without to reproduce permission, this book or portionsin writing, thereof, from in anyChabad form, of without California, permission, Inc. in writing, from Chabad of California, Inc. The Kehot logo is a trademark ofThe Merkos Kehot L’Inyonei logo is a Chinuch,trademark Inc. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Devarim 5780

סב ׳ ׳ ד רבד י ם שת ״ ף Devarim 5780 Followership ** KEY IDEA OF THE WEEK ** Judaism encourages followers and leaders to form a partnership of mutual respect. PARSHAT DEVARIM IN A NUTSHELL The book of Devarim is, in essence, Moses’ renewal of the Israel about the story of the spies and the people’s lack of same covenant that God made with Israel at Mount Sinai. faith that led to forty year wandering in the desert. This time Moses joins the covenant to the next generation, Then he moves on to more recent events, retelling the because they will soon enter the Promised Land and create a stories of their battles and victories over Moab and Ammon society based on the Torah there. And because a covenant and the settlement of their land (on the other side of the often begins with a preamble and an historical outline, this is River Jordan) by the tribes of Reuben and Gad and part of also how parshat Devarim begins. Moses explains the Menashe. The parsha ends with the appointment of Joshua background to the covenant, and then discusses the events as his successor. He will lead the people into the Land. that led to the covenant and its renewal. First we have an introduction which describes the time and QUESTION TO PONDER: place: we are in the last weeks of Moses’ life and the people Why do you think Joshua was chosen to lead after Moses? are camped by the banks of the River Jordan. Moses reminds THE CORE IDEA In the last month of his life, Moses gathered the people and ‘Send men …” In our parsha, it was the people who taught them the laws they were to keep and reminded them requested it: “Then all of you came to me and said, ‘Let us of their history since the Exodus. -

The Bronze Snake

Lesson 12 The Bronze Snake Numbers 20:1-21:9 Numbers 20 And the people of Israel, the whole congregation, came into the wilderness of Zin in the first month, and the people stayed in Kadesh. And Miriam died there and was buried there. 2 Now there was no water for the congregation. And they assembled themselves together against Moses and against Aaron. 3 And the people quarreled with Moses and said, “Would that we had perished when our brothers perished before the LORD! 4 Why have you brought the assembly of the LORD into this wilderness, that we should die here, both we and our cattle? 5 And why have you made us come up out of Egypt to bring us to this evil place? It is no place for grain or figs or vines or pomegranates, and there is no water to drink.” 6 Then Moses and Aaron went from the presence of the assembly to the entrance of the tent of meeting and fell on their faces. And the glory of the LORD appeared to them, 7 and the LORD spoke to Moses, saying, 8 “Take the staff, and assemble the congregation, you and Aaron your brother, and tell the rock before their eyes to yield its water. So you shall bring water out of the rock for them and give drink to the congregation and their cattle.” 9 And Moses took the staff from before the LORD, as he commanded him. 10 Then Moses and Aaron gathered the assembly together before the rock, and he said to them, “Hear now, you rebels: shall we bring water for you out of this rock?” 11 And Moses lifted up his hand and struck the rock with his staff twice, and water came out abundantly, and the congregation drank, and their livestock. -

Chronology of Wilderness Wanderings

mark h lane www.biblenumbersforlife.com CHRONOLOGY OF WILDERNESS WANDERINGS INTRODUCTION It matters where things happened in the Bible. It matters when things happened in the Bible. The Bible tells us only a few dates. Only a handful of locations are undisputed. One thing we know for absolute sure is Mt. Sinai is in Arabia (Gal. 1:17 4:25). The traditional location of Mt. Sinai is wrong. In the time of Paul Arabia did not extend past the Gulf of Aqaba. Believe the Bible, it is the word of God. SUMMARY We subscribe to the conclusions of Bible.ca who propose the following map of the wilderness journey: There are three wilderness journeys: the first [Red Arrows] is from Goshen in Egypt to Mount Sinai (first white spot); the second [Blue Arrows] is from Mount Sinai to Kadesh Barnea (second white spot); the third [Yellow arrows] is from Kadesh Barnea to Jericho (third spot). Bible.ca provides more detailed maps. However, we like this high level view because the precise location of Mt. Sinai and Kadesh Barnea cannot be proven. The main point for the Bible student to realise is all of what is called the Sinai Peninsula today was part of Egypt until 106 AD when the Romans annexed it. The whole purpose of the Exodus was to draw God’s people out of Egypt. If Mt. Sinai was in Egypt the whole mission would have Bible.ca provides solid arguments why the traditional Red Sea routes been a failure. cannot fit the Biblical account. The route they propose fits Paul tells us Mt. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

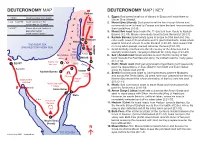

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

Interactive Timeline of Bible History

Interactive Timeline Home China India Published in 2007 by Shawn Handran. Released in 2012 under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Uported License. Oceana-New World Greco-Roman Egypt Mesopotamia-Assyria Patriarchs Period Abraham to Joseph Interactive Timeline of Events in the Bible Exodus Period in Perspective of World History Judges Period Using Bible Chronologies Described in Halley’s Bible Handbook, The Ryrie Study Bible Kings Period and The Mystery of History with Comparative World Chronologies from Wikipedia Exile & Restoration Jesus the Messiah The Old Testament Or click here to begin Prehistory to 2100 bc China Period of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors ca. 2850 Start of Indus Valley civilization ca. 3000 India Published in 2007 by Shawn Handran. Released in 2012 under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Uported License. Caral civilization (Peru) ca. 2700 Oceana-New World Helladic (Greece) & Minoan civilization (Crete) ca. 2800 Greco-Roman Ancient Egyptian civilization ca. 3100 Egypt Old Kingdom Rise of Mesopotamian civilization ca. 3400 Akkadian Empire Mesopotamia-Assyria Tower of Babel (uncertain) The Age of the Patriarchs – Click Here to View Genealogy Abraham Adam Noah’s Flood born in Ur 4176 Click here to view how dates shown here were calculated 2520 2166 4000 bc Genesis 1-11 2500 bc 2100 bc The Old Testament Dates on this page are approximate and difficult to verify Xia Dynasty 2070 2100 to 1700 bc China Xia Dynasty Late Harappan 1700 India Published in 2007 by Shawn -

Shelach Lecha Sermon June 20, 2020

Whether Imagination is a Source of Power or Disempowerment is Up to You: Sermon on Shlach Lecha This morning, I would like to speak to you about the power of imagination. Here, let me put great emphasis on power. It was none other than Albert Einstein who was able to imagine things happening in the universe that are only now being verified. "Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution." The English word “imagination” come from the Latin imaginare, ‘form an image of, represent’ and imaginari, ‘picture to oneself’. The ability to picture ourselves in a different situation, or the world not as it but as it could be, gives us power. Or, as Mohammed Ali once said, “The man who has no imagination has no wings!” If imagination gives us the power to see what can be and inspire us to achieve it, then logic would dictate that a person without imagination can find themselves powerless. In our portion this week, we will see what happens when a people’s imagination fails them, and also how imagination allows us to create new possibilities when the facts say otherwise. In our portion, Shlach Lecha, the Children of Israel stand on the precipice of the promised land in a place on the border called Kadesh Barnea. It is time to fulfill the promise that was made to Abraham and Sarah; time to settle the land. This generation had seen the power of God as no other had before or after them: • They had witnessed the plagues • They had walked on dry land as the sea split • They had stood at Sinai • They had eaten the manna that God had provided as the marched in the midbar In Shlach Lecha, the text begins: ב ְשׁ ַלח ְל ֣] ֲאנָ ֗ ִשׁים וְיָ ֨ ֻתר ֙וּ ֶאת־ ֶ֣א ֶרץ Send out for yourself men who will scout ְכּ ֔נַ ַען ֲא ֶשׁר־ ֲא ִ֥ני נ ֹ ֵ֖תן ִל ְב ֵ֣ני יִ ְשׂ ָר ֵ֑אל ִ֣אישׁ the Land of Canaan, which I am giving to ֶא ָח ֩ד ֨ ִאישׁ ֶא ֜ ָחד ְל ַמ ֵ֤טּה ֲאב ֹ ָתי ֙ו ִתּ ְשׁ ֔ ָלחוּ the children of Israel. -

Israel- Language and Culture.Pdf

Study Guide Israel: Country and Culture Introduction Israel is a republic on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea that borders Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. A Jewish nation among Arab and Christian neighbors, Israel is a cultural melting pot that reflects the many immigrants who founded it. Population: 8,002,300 people Capital: Jerusalem Languages: Hebrew and Arabic Flag of Israel Currency: Israeli New Sheckel History Long considered a homeland by various names—Canaan, Judea, Palestine, and Israel—for Jews, Arabs, and Christians, Great Britain was given control of the territory in 1922 to establish a national home for the Jewish people. Thousands of Jews immigrated there between 1920 and 1930 and laid the foundation for communities of cooperative villages known as “kibbutzim.” A kibbutz is a cooperative village or community, where all property is collectively owned and all members contribute labor to the group. Members work according to their capacity and receive food, clothing, housing, medical services, and other domestic services in exchange. Dining rooms, kitchens, and stores are central, and schools and children’s dormitories are communal. Assemblies elected by a vote of the membership govern each village, and the communal wealth of each village is earned through agricultural, entrepreneurial, or industrial means. The first kibbutz was founded on the bank of the Jordan River in 1909. This type of community was necessary for the early Jewish immigrants to Palestine. By living and working collectively, they were able to build homes and establish systems to irrigate and farm the barren desert land. At the beginning of the 1930s a large influx of Jewish immigrants came to Palestine from Germany because of the onset of World War II.