Rothenberg, B., Segal, I. and Khalaily, H., 2004. Late Neolithic And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Company Overview

Gilead Sciences Advancing Therapeutics. Improving Lives. Company Overview Gilead Sciences, Inc. is a research-based biopharmaceutical Key Moments in Our History company that discovers, develops and commercializes innovative medicines in areas of unmet medical need. With each new 1987 Gilead founded discovery and investigational drug candidate, we seek to improve AmBisome® approved (Europe) the care of patients living with life-threatening diseases around the 1990 world. Gilead’s therapeutic areas of focus include HIV/AIDS, liver 1991 Nucleotides in-licensed from diseases, cancer and inflammation, and serious respiratory and IOCB Rega cardiovascular conditions. 1996 Vistide® approved Our portfolio of 18 marketed 1999 NeXstar acquired; products contains a number Tamiflu® approved of category firsts, including complete treatment regimens 2001 Viread® approved for HIV and chronic hepatitis Hepsera® approved C infection available in once- 2002 daily single pills. Gilead’s 2003 Triangle Pharmaceuticals acquired; portfolio includes Harvoni® Emtriva® approved (ledipasvir 90 mg/sofosbuvir ® ® 400 mg) for chronic hepatitis C, 2004 Macugen , Truvada approved which is a complete antiviral 2006 Atripla®, Ranexa® approved; treatment regimen in a single Corus, Raylo, Myogen acquired tablet that provides high cure ® rates and a shortened course 2007 Letairis approved; Cork, Ireland, Harvoni, Gilead’s once-daily single of therapy for many patients. manufacturing facility acquired tablet HCV regimen. from Nycomed ® 2008 Lexiscan , Viread® for hepatitis B Nearly 30 Years of Growth approved Gilead was founded in 1987 in Foster City, California. Since CV Therapeutics acquired then, Gilead has become a leading biopharmaceutical company 2009 ® with a rapidly expanding product portfolio, a growing pipeline of 2010 Cayston approved; investigational drugs and more than 7,000 employees in offices CGI Pharmaceuticals acquired across six continents. -

MAY 2016 / NISAN - IYAR 5776 from Rabbi Dr

he uz at T News From B’naiB Zion CongregationZ inBZ Shreveport, LA MAY 2016 / NISAN - IYAR 5776 From Rabbi Dr. Jana De Benedetti I really do try to do good things. I really do try to make the world a better place. Stuff Happens I try to see people the way I think that they want to be seen. I like to believe that if I treat someone with respect, then I can get respect in return. I think that I want to believe in “karma.” If I do good things, then life will be good, and good things will come my way. In the Torah it teaches that if we keep the Commandments, and live life justly, and with mercy, then good things will happen, and we can walk humbly with God. What does it mean when that doesn’t happen? When you eat healthy, and exercise, and get enough sleep, and wash your hands – and you still get sick? When you are kind, and generous, and sweet, and someone takes advantage of that? When you think you did all the right things, followed all the instructions, crossed your t’s and dotted your i’s, and still get rejected? That’s just not right…Why does that happen? What do you do about it? Some people yell. They get angry. They try to force things to go their way. Their blood pressure goes up – and so does the blood pressure of everyone around them. They believe: “This can’t be happening to me.” Some people shut down. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls

Journal of Theology of Journal Southwestern dead sea scrolls sea dead SWJT dead sea scrolls Vol. 53 No. 1 • Fall 2010 Southwestern Journal of Theology • Volume 53 • Number 1 • Fall 2010 The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls Peter W. Flint Trinity Western University Langley, British Columbia [email protected] Brief Comments on the Dead Sea Scrolls and Their Importance On 11 April 1948, the Dead Sea Scrolls were announced to the world by Millar Burrows, one of America’s leading biblical scholars. Soon after- wards, famed archaeologist William Albright made the extraordinary claim that the scrolls found in the Judean Desert were “the greatest archaeological find of the Twentieth Century.” A brief introduction to the Dead Sea Scrolls and what follows will provide clear indications why Albright’s claim is in- deed valid. Details on the discovery of the scrolls are readily accessible and known to most scholars,1 so only the barest comments are necessary. The discovery begins with scrolls found by Bedouin shepherds in one cave in late 1946 or early 1947 in the region of Khirbet Qumran, about one mile inland from the western shore of the Dead Sea and some eight miles south of Jericho. By 1956, a total of eleven caves had been discovered at Qumran. The caves yielded various artifacts, especially pottery. The most impor- tant find was scrolls (i.e. rolled manuscripts) written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the three languages of the Bible. Almost 900 were found in the Qumran caves in about 25,000–50,000 pieces,2 with many no bigger than a postage stamp. -

TURKEY BASIC COUNTRY DATA Total Population

TURKEY BASIC COUNTRY DATA Total Population: 72,752,325 Population 0-14 years: 26% Rural population: 30% Population living under USD 1.25 a day: 2.7% Population living under the national poverty line: 18.1% Income status: Upper middle income economy Ranking: High human development (ranking 92) Per capita total expenditure on health at average exchange rate (US dollar): 571 Life expectancy at birth (years): 73 Healthy life expectancy at birth (years): 62 BACKGROUND INFORMATION The first case of VL in Turkey was reported from Trabzon, in the eastern part of the Black Sea Region, in 1916; the second from Izmir, in the Aegean Region, in 1918. VL is endemic, with sporadic cases reported from 38 of 81 provinces (in 2008, there were less than 10 cases). Most cases occur at the Armenian border, in the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Central Anatolia Regions [1,2]. Dogs seem to be the main animal reservoir with a high seroprevalence of over 20% in some of the endemic regions [3]. CL is caused by L. tropica and is more prevalent in southeastern Anatolia [4], where 96% of cases are located, central Anatolia, the western regions, and, less frequently, in the Mediterranean and Aegean Regions [1,5,6]. In Sanliurfa, southeastern Anatolia, the number of CL cases reported from 1981 to 2000 was 22,335. The reported incidence reached a peak in 1994, with 4,185 cases. There has been a considerable reduction in the number of reported cases from 1995 onwards [7]. A recent upsurge of CL cases in the southeastern Anatolia Region is attributed to the environmental impact of a big irrigation project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi-GAP) [8]. -

Wildlife Viewing

Wildlife Viewing Common Yukon roadside flowers © Government of Yukon 2019 ISBN 987-1-55362-830-9 A guide to common Yukon roadside flowers All photos are Yukon government unless otherwise noted. Bog Laurel Cover artwork of Arctic Lupine by Lee Mennell. Yukon is home to more than 1,250 species of flowering For more information contact: plants. Many of these plants Government of Yukon are perennial (continuously Wildlife Viewing Program living for more than two Box 2703 (V-5R) years). This guide highlights Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 the flowers you are most likely to see while travelling Phone: 867-667-8291 Toll free: 1-800-661-0408 x 8291 by road through the territory. Email: [email protected] It describes 58 species of Yukon.ca flowering plant, grouped by Table of contents Find us on Facebook at “Yukon Wildlife Viewing” flower colour followed by a section on Yukon trees. Introduction ..........................2 To identify a flower, flip to the Pink flowers ..........................6 appropriate colour section White flowers .................... 10 and match your flower with Yellow flowers ................... 19 the pictures. Although it is Purple/blue flowers.......... 24 Additional resources often thought that Canada’s Green flowers .................... 31 While this guide is an excellent place to start when identi- north is a barren landscape, fying a Yukon wildflower, we do not recommend relying you’ll soon see that it is Trees..................................... 32 solely on it, particularly with reference to using plants actually home to an amazing as food or medicines. The following are some additional diversity of unique flora. resources available in Yukon libraries and bookstores. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25 April – 5 May 2019

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25th April – 5th May 2019 Trip Report author: Steve Arlow [email protected] Blog for further images: https://stevearlowsbirding.blogspot.com/ Purpose of this Trip Report / Guide I have visited Israel numerous times since spring since 2012 and have produced birding trip reports for each of those visits however for this report I have collated all of my previous useful information and detail, regardless if they were visited this year or not. Those sites not visited this time around are indicated within the following text. However, if you want to see the individual trip reports the below are detailed in Cloudbirders. March 2012 March 2013 April – May 2014 March 2016 April – May 2016 March 2017 April – May 2018 Summary of the Trip This year’s trip in late April into early May was not my first choice for dates, not even my second but it delivered on two key target species. Originally I had wanted to visit from mid-April to catch the Levant Sparrowhawk migration that I have missed so many previous times before however this coincided with Passover holidays in Israel and accommodation was either not available (Lotan) or bonkersly expensive (Eilat) plus the car rental prices were through the roof and there would be holiday makers everywhere. I decided then to return in March and planned to take in the Hula (for the Crane spectacle), Mt. Hermon, the Golan, the Beit She’an Valley, the Dead Sea, Arava and Negev as an all-rounder. However I had to cancel the day I was due to travel as an issue arose at home that I just had to be there for. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

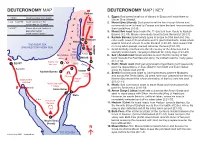

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

The Jewish Federations of North America Urges Caution And

Volume XIV Issue 4 Iyar/Sivan 5775 May 2015 The Jewish Federations of North America Urges Caution and Congressional Review of Any Iran Deal April 2, 2015 The Administration has repeatedly reaffirmed that “it is unacceptable for Iran to have a nuclear weapon.” Even during the current negotiations, the White House has often said, “a bad deal is worse than no deal.” We appreciate the good faith efforts made by the Admin- istration and the other members of the P5+1. We all hope that a diplomatic solution to stop Iran from acquiring a View photos of the community Yom HaShoah nuclear weapon is possible. Commemoration on pages 16-17. However, the framework presented today leaves vital is- sues woefully unresolved. The agreement provides scant detail on how the phased sanction relief will be imple- CAMPAIGN NEWS mented. It contains insufficient clarity on how Iranian Major Gifts Brunch to be held on May 17 adherence to the agreement will be verified. And it is The Major Gifts Champagne Brunch will be held on Sun- ambiguous on what penalties will be imposed if Iran fails day, May 17 at 11:00 a.m. at the home of Linda and Leon to fulfill its commitments. Ravvin. The guest speakers will be Jeff Polson and Tif- fany Fabing, Executive Director and Board Coordinator of A weak agreement presents a clear and present danger to the Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence. all nations. It is also likely to lead other countries in the With financial assets exceeding $100 million, the Jew- region to seek their own nuclear capabilities, resulting in ish Heritage Fund for Excellence (JHFE) is committed to a proliferation of nuclear weapons in a part of the world improving health and fostering a vibrant Jewish Commu- already destabilized by Iranian proxies spreading terror- nity in Metropolitan Louisville and the Commonwealth of ism and fomenting extremism.