Roman Roads, Physical Remains, Organization and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Itinerary Is Subject to Change. •

Itinerary is Subject to Change. • Welcome to Israel! This evening, meet in the lobby of the new Royal Beach Hotel in Tel Aviv. After a short introduction, board the bus and head to a special venue for an opening dinner and introduction to the mission. Several special guests will join us for the evening as well. Overnight, Royal Beach Hotel, Tel Aviv Tel Aviv • Following breakfast, transfer to the airport for a flight to Eilat. Upon arrival, proceed to Timna Park. Pass through the front gates to the newly built chronosphere and become immersed in a fascinating 360-degree multimedia experience called the Mines of Time. Through a dramatic audio-visual computer simulation and state-of-the-art animation, learn about ancient Egyptian and Midianite cultures dating from the time of the Exodus - a prelude to what we’ll encounter further into the park. Solomon’s Pillars at Timna Park Following lunch by Timna Park’s lake, continue to Kibbutz Grofit for a visit to the Red Mountain Therapeutic Riding Center, which focuses on children from Israel suffering from mild to severe emotional and physical disabilities. A representative from the center will lead a tour of the facility and provide an update of the center’s current activities. Proceed to Kibbutz Yahel, a vibrant agricultural kibbutz with a focus on the tourism industry. JNF is continuing its long-standing partnership with Kibbutz Yahel and Mushroom at Timna Park developing a recreational and educational park in the heart of the Southern Arava that will be a tranquil, green retreat for tourists and travelers. -

MAY 2016 / NISAN - IYAR 5776 from Rabbi Dr

he uz at T News From B’naiB Zion CongregationZ inBZ Shreveport, LA MAY 2016 / NISAN - IYAR 5776 From Rabbi Dr. Jana De Benedetti I really do try to do good things. I really do try to make the world a better place. Stuff Happens I try to see people the way I think that they want to be seen. I like to believe that if I treat someone with respect, then I can get respect in return. I think that I want to believe in “karma.” If I do good things, then life will be good, and good things will come my way. In the Torah it teaches that if we keep the Commandments, and live life justly, and with mercy, then good things will happen, and we can walk humbly with God. What does it mean when that doesn’t happen? When you eat healthy, and exercise, and get enough sleep, and wash your hands – and you still get sick? When you are kind, and generous, and sweet, and someone takes advantage of that? When you think you did all the right things, followed all the instructions, crossed your t’s and dotted your i’s, and still get rejected? That’s just not right…Why does that happen? What do you do about it? Some people yell. They get angry. They try to force things to go their way. Their blood pressure goes up – and so does the blood pressure of everyone around them. They believe: “This can’t be happening to me.” Some people shut down. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25 April – 5 May 2019

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25th April – 5th May 2019 Trip Report author: Steve Arlow [email protected] Blog for further images: https://stevearlowsbirding.blogspot.com/ Purpose of this Trip Report / Guide I have visited Israel numerous times since spring since 2012 and have produced birding trip reports for each of those visits however for this report I have collated all of my previous useful information and detail, regardless if they were visited this year or not. Those sites not visited this time around are indicated within the following text. However, if you want to see the individual trip reports the below are detailed in Cloudbirders. March 2012 March 2013 April – May 2014 March 2016 April – May 2016 March 2017 April – May 2018 Summary of the Trip This year’s trip in late April into early May was not my first choice for dates, not even my second but it delivered on two key target species. Originally I had wanted to visit from mid-April to catch the Levant Sparrowhawk migration that I have missed so many previous times before however this coincided with Passover holidays in Israel and accommodation was either not available (Lotan) or bonkersly expensive (Eilat) plus the car rental prices were through the roof and there would be holiday makers everywhere. I decided then to return in March and planned to take in the Hula (for the Crane spectacle), Mt. Hermon, the Golan, the Beit She’an Valley, the Dead Sea, Arava and Negev as an all-rounder. However I had to cancel the day I was due to travel as an issue arose at home that I just had to be there for. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

AVINOAM MEIR Birth: November 1, 1946 Place of Birth: Israel Address

1 CURRICULUM VITAE (January 2021) PERSONAL DETAILS Name: AVINOAM MEIR Birth: November 1, 1946 Place of Birth: Israel Address: (w) Department of Geography and Environmental Development Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Beer-Sheva, Israel Tel.: 0528795994 E-mail: ameir@ bgu.ac.il (h) 24/50 Efraim Katzir, Hod HaSharon, ISRAEL, 4528253 EDUCATION B.A.: 1972, Tel Aviv University, Israel, Geography (cum laude). M.A.: 1975, University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, Geography Thesis Title: Spatial diffusion of Passenger Cars in Ohio: A Study in Pattern and Determinants (Advisor: Professor Robert B. South). Ph.D.: 1977, University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, Geography Dissertation Title: Diffusion, Spread, and Spatial Innovation Transmission Processes: The Adoption of Industry among Kibbutzim in Israel as a Case Study (Advisor: Professor Roger M. Selya). EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 1971-72: Teaching Assistant, Department of Geography, Tel Aviv University, Israel. 1974-77: Teaching Assistant, Department of Geography, University of Cincinnati, USA. 1977-78: Lecturer, HaNegev College and Beit-Berl College, Israel (part-time). 1977-81: Lecturer, Department of Geography, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 2 1979-82: Research Fellow, Blaustein Institute for Desert Research, Sde, Boker, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 1981- 87: Senior Lecturer, Department of Geography, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Tenure: 1981). 1984-85: Visiting Professor, Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, USA. 1987-88: Research Fellow, Blaustein Institute for Desert Research, Sde Boker, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 1987-96: Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 1989-96: Associate Professor, Sapir College, Israel (part-time). -

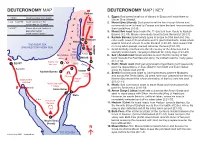

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

The Israel National Trail

Table of Contents The Israel National Trail ................................................................... 3 Preface ............................................................................................. 5 Dictionary & abbreviations ......................................................................................... 5 Get in shape first ...................................................................................................... 5 Water ...................................................................................................................... 6 Water used for irrigation ............................................................................................ 6 When to hike? .......................................................................................................... 6 When not to hike? ..................................................................................................... 6 How many kilometers (miles) to hike each day? ........................................................... 7 What is the direction of the hike? ................................................................................ 7 Hike and rest ........................................................................................................... 7 Insurance ................................................................................................................ 7 Weather .................................................................................................................. 8 National -

Israel Trail

Hillel Sussman he Israel Bike Trail is a national project for the construction of a mountain bike trail that traverses the entire country from the northernmost and highest point in Israel - TMount Hermon - to the lowest point on earth - the Dead Sea, and to the southernmost point - the city of Eilat on the shores of the Red Sea. Imagine that in just a few short years, you'll be able to hop on your bike on Mount Hermon and pedal away until you reach Eilat. The project is led by the Israel Nature Pedal your way to an appreciation of Israel’s landscapes and history and Parks Authority with financial support The Israel Bike Trail from the Ministry of Tourism and the Israel Government Tourist Corporation as well as other government ministries, including the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. The concept is that anyone who bikes the trail will learn about the diverse landscapes and cultures of Israel. In planning the trail, we have attempted to connect to as many important tourist sites as possible into a single contiguous trail. The trail is planned to extend over 1,200 kilometers (approximately 750 miles), making it one of the longest trails in the world, and perhaps the most beautiful and diverse. To create the trail, teams are currently deployed throughout Israel, seeking the best possible routes. The trail is being constructed with the highest possible mountain biking trail standards. Parts of it are being built by volunteers and others by professional trail builders. We set several principles for the planning phase: • Rider services - Each day begins and ends at a place where riders can sleep, eat and, if necessary, have their bikes repaired. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath.