RESEARCHES in the SOUTHERN ARABAH 1959–1990 Summary Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAU Archaeology the Jacob M

TAU Archaeology The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities | Tel Aviv University Number 4 | Summer 2018 Golden Jubilee Edition 1968–2018 TAU Archaeology Newsletter of The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities Number 4 | Summer 2018 Editor: Alexandra Wrathall Graphics: Noa Evron Board: Oded Lipschits Ran Barkai Ido Koch Nirit Kedem Contact the editors and editorial board: [email protected] Discover more: Institute: archaeology.tau.ac.il Department: archaeo.tau.ac.il Cover Image: Professor Yohanan Aharoni teaching Tel Aviv University students in the field, during the 1969 season of the Tel Beer-sheba Expedition. (Courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University). Photo retouched by Sasha Flit and Yonatan Kedem. ISSN: 2521-0971 | EISSN: 252-098X Contents Message from the Chair of the Department and the Director of the Institute 2 Fieldwork 3 Tel Shimron, 2017 | Megan Sauter, Daniel M. Master, and Mario A.S. Martin 4 Excavation on the Western Slopes of the City of David (‘Giv’ati’), 2018 | Yuval Gadot and Yiftah Shalev 5 Exploring the Medieval Landscape of Khirbet Beit Mamzil, Jerusalem, 2018 | Omer Ze'evi, Yelena Elgart-Sharon, and Yuval Gadot 6 Central Timna Valley Excavations, 2018 | Erez Ben-Yosef and Benjamin -

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

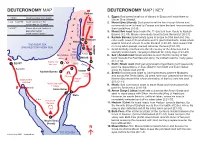

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

Israel- Language and Culture.Pdf

Study Guide Israel: Country and Culture Introduction Israel is a republic on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea that borders Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. A Jewish nation among Arab and Christian neighbors, Israel is a cultural melting pot that reflects the many immigrants who founded it. Population: 8,002,300 people Capital: Jerusalem Languages: Hebrew and Arabic Flag of Israel Currency: Israeli New Sheckel History Long considered a homeland by various names—Canaan, Judea, Palestine, and Israel—for Jews, Arabs, and Christians, Great Britain was given control of the territory in 1922 to establish a national home for the Jewish people. Thousands of Jews immigrated there between 1920 and 1930 and laid the foundation for communities of cooperative villages known as “kibbutzim.” A kibbutz is a cooperative village or community, where all property is collectively owned and all members contribute labor to the group. Members work according to their capacity and receive food, clothing, housing, medical services, and other domestic services in exchange. Dining rooms, kitchens, and stores are central, and schools and children’s dormitories are communal. Assemblies elected by a vote of the membership govern each village, and the communal wealth of each village is earned through agricultural, entrepreneurial, or industrial means. The first kibbutz was founded on the bank of the Jordan River in 1909. This type of community was necessary for the early Jewish immigrants to Palestine. By living and working collectively, they were able to build homes and establish systems to irrigate and farm the barren desert land. At the beginning of the 1930s a large influx of Jewish immigrants came to Palestine from Germany because of the onset of World War II. -

Wild God in the Wilderness: Why Does Yahweh Choose to Appear in the Wilderness in the Book of Exodus?

WILD GOD IN THE WILDERNESS: WHY DOES YAHWEH CHOOSE TO APPEAR IN THE WILDERNESS IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS? by NARELLE JANE COETZEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT: The wilderness is an unlikely place for Yahweh to appear; yet some of the most profound encounters between Yahweh and ancient Israel occur in this isolated, barren, arid and marginal landscape. Thus, via John A. Beck’s narrative-geography method, which prioritises the role of the geographical setting of the biblical narrative, the question of ‘why does Yahweh choose to appear in the wilderness?’ is examined in reference to four Exodus theophanic passages (Exodus 3:1-4:17, 19:1-20:21, 24:9-18 and 33:18-34). First, a biblical working definition of the wilderness is developed, and the specific geographic elements in each passage discussed. Subsequently, the characterisation of Yahweh’s appearances is investigated, via the signs Yahweh used to appear, the words Yahweh speaks and the human experience of Yahweh in the wilderness space. -

403 Ancient Water Management in The

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 403-421 U. AVNER 403 ANCIENT WATER MANAGEMENT IN THE SOUTHERN NEGEV UZI AVNER INTRODUCTION The southern Negev is an extremely arid area, with summer temperatures above 400C, an average annual precipitation of 28 mm, and an annual potential evaporation rate of 4000 mm. This negative water balance causes the area to be poor in water sources and limits the Saharo-Arabian vegetation almost to- tally to wadi beds. Certainly, the desert presents several obstacles to the devel- opment of human communities, the foremost of which is the scarcity of water, for drinking, for everyday uses, for animals and for agriculture. Considering the environmental conditions, one would expect the Southern Negev to be al- most devoid of ancient remains of human presence and activity. However, the harshest part of this area, from ‘Uvda Valley and southward (see Map 1), is surprisingly rich in archaeological sites. A complete sequence of settlement is found during the last 10,000 years, with a wide range of activi- ties such as hunting, grazing, agriculture, trade, copper production, some gold production and others (Avner et al 1994). In this article I will describe several methods of water exploitation in the region. The first will concern the early agricultural settlement in ‘Uvda Valley, 6th to 3rd millennia B.C., the others relate to the Nabatean and the Early Islamic period. AGRICULTURAL SETTLEMENT IN ‘UVDA VALLEY ‘Uvda Valley (Wadi ‘Uqfi in Arabic), 40 km north of the Gulf of Aqaba (Fig. 1), was first briefly described by A. Musil (1907:180-182, 1926:85). -

BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN the Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University

BIBLICAL RESEARCH BULLETIN The Academic Journal of Trinity Southwest University ISSN 1938-694X Volume VII Number 8 The Jordan River Valley, the Jordan River and the Jungle of the Jordan Gary A. Byers Abstract: This brief popular article provides a description of the southern Jordan Valley as a background for the excavation at Tall el-Hammam on the eastern Jordan Disk. It has previously appeared in several publications, and is republished here with permission from the author. © Copyright 2007, Trinity Southwest University Special copyright, publication, and/or citation information: Biblical Research Bulletin is copyrighted by Trinity Southwest University. All rights reserved. Article content remains the intellectual property of the author. This article may be reproduced, copied, and distributed, as long as the following conditions are met: 1. If transmitted electronically, this article must be in its original, complete PDF file form. The PDF file may not be edited in any way, including the file name. 2. If printed copies of all or a portion of this article are made for distribution, the copies must include complete and unmodified copies of the article’s cover page (i.e., this page). 3. Copies of this article may not be charged for, except for nominal reproduction costs. 4. Copies of this article may not be combined or consolidated into a larger work in any format on any media, without the written permission of Trinity Southwest University. Brief quotations appearing in reviews and other works may be made, so long as appropriate credit is given and/or source citation is made. For submission requirements visit www.BiblicalResearchBulletin.com. -

The Levantine War-Records of Ramesses Iii: Changing Attitudes, Past, Present and Future*

03 James Levantine_Antiguo Oriente 08/06/2018 04:37 p.m. Página 57 THE LEVANTINE WAR-RECORDS OF RAMESSES III: CHANGING ATTITUDES, PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE* PETER JAMES [email protected] Independent researcher London, United Kingdom Summary: The Levantine War-Records of Ramesses III: Changing Attitudes, Past, Present and Future This paper begins with a historiographic survey of the treatment of Ramesses III’s claimed war campaigns in the Levant. Inevitably this involves questions regarding the so-called “Sea Peoples.”1 There have been extraordinary fluctuations in attitudes towards Ramesses III’s war records over the last century or more—briefly reviewed and assessed here. His lists of Levantine toponyms also pose considerable problems of interpretation. A more systematic approach to their analysis is offered, concentrat- ing on the “Great Asiatic List” from the Medinet Habu temple and its parallels with a list from Ramesses II. A middle way between “minimalist” and “maximalist” views of the extent of Ramesses III’s campaigns is explored. This results in some new iden- tifications which throw light not only on the geography of Ramesses III’s campaigns but also his date. Keywords: Ancient Egypt – Canaan – Late Bronze Age – War Records – Toponymy Resumen: Los registros de la guerra levantina de Ramsés III: Actitudes cam- biantes, pasado, presente y futuro Este artículo comienza con un recorrido historiográfico del tratamiento de las supues- tas campañas bélicas de Ramsés III en el Levante. Inevitablemente esto implica pre- * I would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of the late David Lorton for all his help on Egyptological matters. -

Proto-Alphabetic Inscriptions from the Wadi Arabah

Colless, Brian E. Proto-alphabetic inscriptions from the Wadi Arabah Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 8, 2010 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “Proto-alphabetic inscriptions from the Wadi Arabah”[en línea]. Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 8 (2010). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/proto-alphabetic-inscriptions-wadi-arabah.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). PROTO-ALPHABETIC INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE WADI ARABAH* BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: Proto-alphabetic Inscriptions from the Wadi Arabah Three early West Semitic inscriptions from the Arabah valley are studied here, all of them apparently connected with the Egyptian copper-mining activity in the region, notably at Timna, in the period of the Ramessides. The most striking detail in these texts is a sign corresponding to an Egyptian hieroglyph (N6B ) which depicts two serpents guarding the sun-disc, and another with one serpent (N6 ,); these never appear on conventional tables of early alphabetic letters; this leads to a critical reappraisal of current identifications of the original picture-signs, and elaboration of a new system of interpreting early Canaanite inscriptions, involving recognition that the signs could sometimes stand for whole words and could also be used as rebuses. -

Rothenberg, B., Segal, I. and Khalaily, H., 2004. Late Neolithic And

B. Rothenberg et al. iams 24, 2004, 17-28 Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic copper smelting at the Yotvata oasis (south-west Arabah) Beno Rothenberg, Irina Segal and Hamoudi Khalaily Site 44 at Yotvata, its discovery and excavation the only major source of water and fuel for the often large- Yotvata is the modern name of an oasis located in the Arabah scale mining and smelting activities in the region, especial- rift valley (G.R.155.923), about 40 km north of the Gulf of ly in the Timna Valley, the Wadi Amram and on numerous Eilat/Aqabah (Fig. 1). At the time of the first visit at the site hillsites along the mineralized mountain range of the south- western Arabah, one of which, Site 44, was located at Yot- vata itself (Rothenberg 1999). Site 44 (G.R.15529234), located on top of a hill next to the Kibbutz settlement, was first recorded by Rothenberg in 1956 (Fig. 2) and again investigated by Rothenberg’s ‘Ara- bah Expedition’ in 19602 and in 20013. The architecture of this site (Fig. 3), and its location on a steep, high cliff over- looking the oasis, indicated that it was a stronghold to guard this rich source of water and wood. Related to the architec- Fig. 2. Hill site 44 at Yotvata Fig. 1. Map of the Arabah and adjacent regions by Beno Rothenberg in the early 1950s, the oasis was still called ‘Ein Ghadyan1, a name presumably derived from the nearby Roman station ad-Dianam (Tabula Iteneraria Peutin- geriana, Segm.IX, Miller 1962). The oasis consisted of sev- eral shallow wells, a grove of date palms and an extensive area of tamarisks.