FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE a Master's Exhibition of Print Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the many citizens, staff, and community groups who provided extensive input for the development of this Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan. The project was a true community effort, anticipating that this plan will meet the needs and desires of all residents of our growing County. SHASTA COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Glenn Hawes, Chair David Kehoe Les Baugh Leonard Moty Linda Hartman PROJECT ADVISORY COMMITTEE Terry Hanson, City of Redding Jim Milestone, National Park Service Heidi Horvitz, California State Parks Kim Niemer, City of Redding Chantz Joyce, Stewardship Council Minnie Sagar, Shasta County Public Health Bill Kuntz, Bureau of Land Management Brian Sindt, McConnell Foundation Jessica Lugo, City of Shasta Lake John Stokes, City of Anderson Cindy Luzietti, U.S. Forest Service SHASTA COUNTY STAFF Larry Lees, County Administrator Russ Mull, Department of Resource Management Director Richard Simon, Department of Resource Management Assistant Director Shiloe Braxton, Community Education Specialist CONSULTANT TEAM MIG, Inc. 815 SW 2nd Avenue, Suite 200 Portland, Oregon 97204 503.297.1005 www.migcom.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Plan Purpose 1 Benefits of Parks and Recreation 2 Plan Process 4 Public Involvement 5 Plan Organization 6 2. Existing Conditions ................................................................................ 7 Planning Area 7 Community Profile 8 Existing Resources 14 3. -

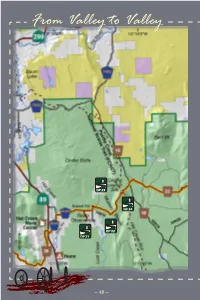

From Valley to Valley

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Social Science Program Visitor Services Project Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study [Insert image here] OMB Control Number:1024-0224 Current Expiration Date: 8/31/2014 2 Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Lassen Volcanic National Park P.O. Box 100 Mineral, CA 96063 IN REPLY REFER TO: January/June 2012 Dear Visitor: Thank you for participating in this study. Our goal is to learn about the expectations, opinions, and interests of visitors to Lassen Volcanic National Park. This information will assist us in our efforts to better manage this park and to serve you. This questionnaire is only being given to a select number of visitors, so your participation is very important! It should only take about 20 minutes to complete. Please complete this questionnaire. Seal it in and return it to us in the postage paid envelope provided. If you have any questions, please contact Margaret Littlejohn, NPS VSP Director, Park Studies Unit, College of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 441139, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1139, phone: 208-885-7863, email: [email protected]. We appreciate your help. Sincerely, Darlene M. Koontz Superintendent Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study 3 DIRECTIONS At the end of your visit: 1. Please have the selected individual (at least 16 years old) complete this questionnaire. 2. Answer the questions carefully since each question is different. 3. For questions that use circles (O), please mark your answer by filling in the circle with black or blue ink. -

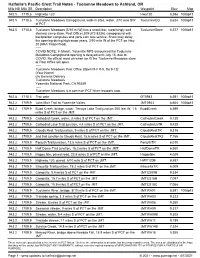

Halfmile's Pacific Crest Trail Notes

Halfmile's Pacific Crest Trail Notes - Tuolumne Meadows to Ashland, OR Mile NB Mile SB Description Waypoint Elev Map 942.5 1710.6 Highway 120 Hwy120 8,596 1008p15 942.5 1710.6 Tuolumne Meadows Campground, walk-in sites, water, 3/10 mile SW TuolumneCG 8,624 1008p15 of PCT. 942.5 1710.6 Tuolumne Meadows [3/10 mi W] has a snack bar, surprisingly well TuolumneStore 8,577 1008p15 stocked camp store, Post Office [209-372-8236], campground with backpacker campsites and yarts.com bus service. Snow may delay the opening during high snow years. 3/10 mile W of the PCT on Hwy 20 [AKA Tioga Road]. ----- COVID NOTE: In March, Yosemite NPS announced the Tuolumne Meadows Campground opening is delayed until July 15, due to COVID. No official word on when (or if) the Tuolumne Meadows store or Post Office will open. ----- Tuolumne Meadows Post Office [Open M-F 9-5, Sa 9-12]: (Your Name) c/o General Delivery Tuolumne Meadows Yosemite National Park, CA 95389 ----- Tuolumne Meadows is a common PCT hiker resupply stop. 942.8 1710.3 Trail gate GT0943 8,591 1008p15 943.2 1709.9 John Muir Trail to Yosemite Valley. JMT0943 8,604 1008p15 943.2 1709.9 Budd Creek, bridge, water, Tenaya Lake Trail junction 200 feet W, 1.5 BuddCreek 8,599 miles S of PCT on the JMT. 943.2 1709.9 Cathedral Creek, water, 3 miles S of PCT on the JMT. CathedralCreek 9,135 943.2 1709.9 Cathedral Lake Trail junction, 4.4 miles S of PCT on the JMT. -

Bistorical Society Quarterly DIRECTOR JOHN TOWNLEY

NEVADA Bistorical Society Quarterly DIRECTOR JOHN TOWNLEY BOARD OF TRUSTEES The Nevada Historical Society was founded in 1904 for the purpose of investigating topics JOHN WRIGHT pertaining to the early history of Nevada and Chairman of collecting relics for a museum at its Reno facility where historical materials of many EDNA PATTERSON kinds are on display to the public and are av- Vice Chairman ailable to students and scholars. ELBERT EDWARDS Membership dues are: annual, S7.50; student, S3; sustaining, $25; life, $100; and patron, RUSSELL ELLIOTT $250. Membership applications and dues should be sent to the director. RUS-SELL McDONALD MARY ELLEN SADOVICH The Nevada Historical Society Quarterly pub- lishes articles, interpretive essays , and docu- WILBU R SHIPPERSON ments which deal with the history of Nevada . and of the Great Basin area. Particularly wef- come are manuscripts which examne the polit- ical, economic, cultural, and constitutional aspects of the history of this region. Material submitted for publication should be sent to the N. H .5. Quarterly, 4582 Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, Nevada 89109. Footnotes should be placed at the end of the manuscript, \vhich should be typed double spaced. The evalua- tion process will take approximately six to ten weeks. lassaere - Lakes "',,' , /\...y' ////f/, : //T;V; :.r// " . /, , . , f''''" . " ''///: ':/ /' / ,: / / , /" ,/,/ //'/ . ' -' . " . /r,///, '//. /// /", This portrayal of the 1850 Massacre was drawn by Paul Nyland as one of a series of historically oriented newspaper advertisements for Harold's Club of Reno, Massacre! What Massacre? An Inquiry into the Massacre of 1850 by Thomas N. Layton MASSACRE LAKE (Washoe County, Nevada) Some small lakes, or dry sinks, also called Massacre Lakes, east of Vya in the northern portion of the county... -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 1942

QL AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL. 19, NO. 4 JOURNAL APRIL, 1942 wm,' "-c* Naval cadets are earning their wings in Free literature on request for 50 to 175 h.p. hori¬ Spartan trainers powered by Lycoming . zontally opposed or 220 to 300 h.p. radial engines. Write Dept. J42. Specify which literature desired. the aircraft engine whose dependable, eco¬ nomical operation and low maintenance and upkeep costs have been proved through years of use in both the pilot training divi¬ ¥ sions of the Armed Forces and the CPTP. Contractors to the U. S. Army and Navy THE TRAINING PLANE ENGINE OF TODAY .. \ THE PRIVATE PLANE / LYCOMING DIVISION, THE AVIATION CORPORATION \ ENGINE OF TOMORROW / WILLIAMSPORT, PA. l>5 p. CONTENTS * * APRIL, 1942 Cover Picture: Demonstration of Monster Tank Culled (See page 236) Australia: Pacific Base to the Colors! By David W. Bailey 185 Excerpt from a Speech by Congressman Rabaut Before the House of Representatives 189 Correction in Foreign Service Examination Ques¬ AMERICA’S three greatest liners, the tions in March issue 189 . Washington, Manhattan and America, From the Caribbean to Cape Horn by the Pan are now serving their country as Navy American Highway—Photos 190 auxiliaries. New Zealand's Role in World Affairs By Robert B. Stewart 194 Before being called to the Colors, these Convoy three American flag liners were the largest, By James N. Wright 196 fastest and most luxurious passenger ships Selected Questions from the Third and Fourth ever built in this country. Special Foreign Service Examinations of 1941 199 Athens—Photos 201 When our Government called its nationals Editors’ Column home from danger zones in Europe and Radio Bulletin 202 the Orient, thousands of Americans re¬ turned to the United States aboard these News from the Department By Jane Wilson 203 ships. -

Looking for Ishi: Insurgent Movements Through the Yahi Landscape Christopher August University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

Informing Science InSITE - “Where Parallels Intersect” June 2003 Looking for Ishi: Insurgent Movements through the Yahi Landscape Christopher August University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA In memory of Christopher August who recently passed away. He was excited about meeting all of you and so, with great appreciation for his work, we include his last contribution to research. Abstract In 1911 a Yahi man wandered out of the Northern California landscape and into the twentieth century. He was immediately collected and installed at the just opened Anthropology Museum by Alfred Kroeber at the University of California's Parnassus Heights campus. Dedication invitations came from the U.C. Regents led by Phoebe Apperson Hearst. Maintaining the discretion of his indigenous culture this man would not divulge his name. Kroeber named him Ishi, the Yahi word for man. These assembled facts introduce narrative streams that continue to unfold around us. To examine these contingent individuals, events and institutions collectively labeled Ishi myth is to examine our own posi- tion, our horizon. Looking for Ishi is a series of interventions and appropriations of Ishi myth involving video installation, looping DVD, encrypted motion images, web work, streaming video, print objects, written and spoken word, and documentation of the author's own insurgent movements through the Yahi landscape. [The following is a summary of an art, writing, and media project in progress.] Keywords : Ishi, canon, insurgent, media, institutions Ishi In 1911 a Yahi man wandered out of the Northern California landscape and into the twentieth century. He was immediately collected and installed at the just opened Anthropology Museum by Alfred Kroeber at the University of California's Parnassus Heights campus. -

Lassen National Forest Backcountry Discovery Trail! Know Before You Go

Get Ready to Explore! Drive 187 miles of unparalleled beauty. Discover a geological playground. Hike to alpine snowfields. Relax at quiet lakes while raptors soar overhead. Trace the footsteps of Gold Rush emigrants. Discover the heritage of northern California. Welcome to the Lassen National Forest Backcountry Discovery Trail! Know Before You Go The Lassen Backcountry Discovery Trail was established to invite exploration of the remote areas of the Lassen backcountry. The Trail generally follows gravel and dirt roads and is intended for high clearance street- legal vehicles. Expect rough road conditions and slow travel through remote country. Be prepared for downed trees or rocks on the road. Much of the route is under snow in the winter Volcanic views and early spring. There are no restaurants, grocery stores, or gas stations along the main route and cell phone coverage is intermittent. Introduction ~ ~ Stay Current Off-road motor vehicle travel is prohibited in the Lassen National Forest; please stay on designated routes. Call any forest office for updated road condition and project work information that may affect your travel plans. Periodic updates to the Trail maps in this Guide may occur to reflect changes in vehicle use or other revisions. Map updates and other Lassen Backcountry Discovery Trail information may be found at: www.fs.fed.us/r5/lassen/ Your Planning Checklist Lassen National Forest Visitor Map Adequate food, water, and fuel Friends to share the fun, and assist in an emergency Insect repellant and first-aid kit Know how to identify poison oak Toilet paper and shovel to bury human waste GPS unit, binoculars, and camera Campfire permit if you plan to use a fire, barbecue, or camp stove (available for free at most Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, California Department of Forestry/Fire Protection offices or fire stations). -

Corridor 15-104 Section 368 Energy Corridor Regional Reviews - Region 5 May 2019 Corridor 15-104 Honey Lake Corridor

Corridor 15-104 Section 368 Energy Corridor Regional Reviews - Region 5 May 2019 Corridor 15-104 Honey Lake Corridor Corridor Purpose and Rationale The corridor runs north-south along Highway 395. The corridor connects multiple Section 368 energy corridors, creating a continuous corridor network across BLM- and USFS-administered lands between Reno, Nevada, and California. The corridor provides a link to the Reno area where renewable energy is in demand. Input regarding alignment from the Western Utility Group during the WWEC PEIS suggested following this route. There is an application for a gen-tie transmission line to connect the proposed Fish Springs Solar Project (a PV solar project that would be constructed on private lands) to the existing transmission line within the corridor. The proposed Bordertown to California 120kV Transmission Line would be located at the substation at MP 5 and would utilize approximately 0.4 miles of the corridor. Future development within the corridor could be limited between MP 107 and MP 114 because of the reduced corridor width. Corridor location: Corridor history: California (Lassen and Sierra Co.); Nevada - Locally designated prior to 2009 (N) (Washoe Co.) - Existing infrastructure (Y) BLM: Applegate, Eagle Lake, and Sierra • A 345-kV transmission line is within Front Field Offices or adjacent to the entire length of USFS: Humboldt-Toiyabe NF the corridor. Two 345-kV Regional Review Region: Region 5 transmission lines follow a portion of the corridor. Corridor width, length: • A natural gas pipeline is within and Width 500 ft in Applegate FO; 3,500 ft in adjacent to a portion of the corridor. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMBNo. 1024-0018 (June 1991) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission __Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Lassen Volcanic National Park Multiple Property Listing___________________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts______________________________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Overland Emigration, Lassen Region (ca. 1849-ca. 1869) Extractive Industry and Permanent Settlement, Lassen region (ca. 1850-1916) Geologic Studies (Volcanology), Mount Lassen (1863-1953) Tourism and Recreation, Lassen region (ca. 1860-1916) National Park Service Administration, Lassen Volcanic National Park (1916-1953) C. Form Prepared by___________________________________________________ name/title Ann Emmons, Historian; Ted Catton, Historian organization date Historical Research Associates, Inc. February 2004 street & number telephone P.O. Box 7086 (406)721-1958 -

Richard T. Arndt

THE FIRST RESORT OF KINGS ................. 11169$ $$FM 06-09-06 09:46:22 PS PAGE i RELATED TITLES FROM POTOMAC BOOKS Envoy to the Terror: Gouverneur Morris and the French Revolution by Melanie R. Miller Napoleon’s Troublesome Americans: Franco-American Relations, 1804–1815 by Peter P. Hill The Open Society Paradox: Why the Twenty-First Century Calls for More Openness—Not Less by Dennis Bailey ................. 11169$ $$FM 06-09-06 09:46:23 PS PAGE ii ● ● THE FIRST RESORT OF KINGS A MERICAN C ULTURAL D IPLOMACY IN THE T WENTIETH C ENTURY ● ● RICHARD T. ARNDT Potomac Books, Inc. Washington, D.C. ................. 11169$ $$FM 06-09-06 09:46:24 PS PAGE iii First paperback edition published 2006 Copyright ᭧ 2005 by Potomac Books, Inc. Published in the United States by Potomac Books, Inc. (formerly Brassey’s, Inc.). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arndt, Richard T., 1928– The first resort of kings : American cultural diplomacy in the twentieth century / Richard T. Arndt. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57488-587-1 (alk. paper) 1. United States—Relations. 2. Cultural relations—History—20th century. 3. Diplomats—United States—History—20th century. 4. United States. Dept. of State—History—20th century. 5. United States Information Agency— History—20th century. 6. Educational exchanges—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. E744.5.A82 2005 327.73Ј009Ј04—dc22 2004060190 ISBN 1-57488-587-1 (hardcover) ISBN 1-57488-004-2 (paperback) Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute Z39-48 Standard. -

The Wilderness Society

February 3, 2020 Washoe County Commission 1001 E. Ninth Street Reno, NV 89512 Dear Commissioners: On behalf of The Wilderness Society and our more than one million members and supporters, we write to offer our comments on the proposed Truckee Meadows Public Lands Management Act. We appreciate your efforts to develop this legislation. CONSERVATION AREAS AND WILDERNESS The Truckee Meadows Public Lands Management Act presents an opportunity to preserve public lands with exceptionally high wildland conservation value. CONSERVATION AREAS The Wilderness Society conducted a comprehensive scientific analysis of the wildland conservation value of public lands in Washoe County. Our analysis found that public lands in the county contain exceptionally high wildland conservation value, including several areas that are within the top five percent of wildlands conservation value nationally. A copy of the proposal is attached. Based on that analysis, we recommend the establishment of three new national conservation areas, and the expansion of the existing Black Rock Desert-High Rock Canyon Emigrant Trails National Conservation Area. Our proposals, which are attached, include: • North Hays Range National Conservation Area - 237,000 acres • Boulder Mountain National Conservation Area - 525,400 acres • Smoke Creek National Conservation Area - 121,300 acres • Black Rock Desert-High Rock Canyon Emigrant Trails NCA addition - 229,900 acres Recommendation: In order to preserve the exceptional conservation values of certain public lands in the county, include the above national conservation areas in the Truckee Meadows Public Lands Management Act. WILDERNESS In September 2018, The Wilderness Society requested that Washoe County consider protections for over 1.4 million acres of eligible wilderness within the county.