Lassen Volcanic National Park in 1916

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plate Tectonics, Volcanoes, and Earthquakes / Edited by John P

ISBN 978-1-61530-106-5 Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor J. E. Luebering: Senior Manager Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition John P. Rafferty: Associate Editor, Earth Sciences Rosen Educational Services Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager Nicole Russo: Designer Matthew Cauli: Cover Design Introduction by Therese Shea Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plate tectonics, volcanoes, and earthquakes / edited by John P. Rafferty. p. cm.—(Dynamic Earth) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-187-4 ( eBook) 1. Plate tectonics. -

The Climate of Death Valley, California

THE CLIMATE OF DEATH VALLEY, CALIFORNIA BY STEVEN ROOF AND CHARLIE CALLAGAN The notoriously extreme climate of Death Valley records shows significant variability in the long-term, including a 35% increase in precipitation in the last 40 years. eath Valley National Park, California, is widely known for its extreme hot and Ddry climate. High summer temperatures, low humidity, high evaporation, and low pre- cipitation characterize the valley, of which over 1300 km2 (500 mi2) are below sea level (Fig. 1). The extreme summer climate attracts great interest: July and August visitation in Death Valley National Park has doubled in the last 10 years. From June through August, the average temperature at Furnace Creek, Death Valley [54 m (177 ft) below sea level] is 98°F (37°C).1 Daytime high temperatures typically exceed 90°F (32°C) more than half of the year, and temperatures above 120°F (49°C) occur 1 Weather data are reported here in their original units in to order retain the original level of precision re- corded by the observers. FIG. I. Location map of the Death Valley region. Death Valley National Park is outlined in blue, main roads shown in red, and the portion of the park below sea level is highlighted in white. AFFILIATIONS: ROOF—School of Natural Science, Hampshire E-mail: [email protected] College, Amherst, Massachusetts; CALLAGAN—National Park Service, DOI: 10.1 175/BAMS-84-12-1725 Death Valley National Park, Death Valley, California. In final form 17 January 2003 CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Steve Roof, School of Natural © 2003 American Meteorological Society Science, Hampshire College, Amherst, MA 01002 AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY DECEMBER 2003 BAfft I 1725 Unauthenticated | Downloaded 10/09/21 10:14 PM UTC 5-20 times each year. -

Tectonic Influences on the Spatial and Temporal Evolution of the Walker Lane: an Incipient Transform Fault Along the Evolving Pacific – North American Plate Boundary

Arizona Geological Society Digest 22 2008 Tectonic influences on the spatial and temporal evolution of the Walker Lane: An incipient transform fault along the evolving Pacific – North American plate boundary James E. Faulds and Christopher D. Henry Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, 89557, USA ABSTRACT Since ~30 Ma, western North America has been evolving from an Andean type mar- gin to a dextral transform boundary. Transform growth has been marked by retreat of magmatic arcs, gravitational collapse of orogenic highlands, and periodic inland steps of the San Andreas fault system. In the western Great Basin, a system of dextral faults, known as the Walker Lane (WL) in the north and eastern California shear zone (ECSZ) in the south, currently accommodates ~20% of the Pacific – North America dextral motion. In contrast to the continuous 1100-km-long San Andreas system, discontinuous dextral faults with relatively short lengths (<10-250 km) characterize the WL-ECSZ. Cumulative dextral displacement across the WL-ECSZ generally decreases northward from ≥60 km in southern and east-central California, to ~25 km in northwest Nevada, to negligible in northeast California. GPS geodetic strain rates average ~10 mm/yr across the WL-ECSZ in the western Great Basin but are much less in the eastern WL near Las Vegas (<2 mm/ yr) and along the northwest terminus in northeast California (~2.5 mm/yr). The spatial and temporal evolution of the WL-ECSZ is closely linked to major plate boundary events along the San Andreas fault system. For example, the early Miocene elimination of microplates along the southern California coast, southward steps in the Rivera triple junction at 19-16 Ma and 13 Ma, and an increase in relative plate motions ~12 Ma collectively induced the first major episode of deformation in the WL-ECSZ, which began ~13 Ma along the N60°W-trending Las Vegas Valley shear zone. -

Alluvial Fans in the Death Valley Region California and Nevada

Alluvial Fans in the Death Valley Region California and Nevada GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 466 Alluvial Fans in the Death Valley Region California and Nevada By CHARLES S. DENNY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 466 A survey and interpretation of some aspects of desert geomorphology UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1965 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publications as follows: Denny, Charles Storrow, 1911- Alluvial fans in the Death Valley region, California and Nevada. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1964. iv, 61 p. illus., maps (5 fold. col. in pocket) diagrs., profiles, tables. 30 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional Paper 466) Bibliography: p. 59. 1. Physical geography California Death Valley region. 2. Physi cal geography Nevada Death Valley region. 3. Sedimentation and deposition. 4. Alluvium. I. Title. II. Title: Death Valley region. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C., 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.. _ ________________ 1 Shadow Mountain fan Continued Introduction. ______________ 2 Origin of the Shadow Mountain fan. 21 Method of study________ 2 Fan east of Alkali Flat- ___-__---.__-_- 25 Definitions and symbols. 6 Fans surrounding hills near Devils Hole_ 25 Geography _________________ 6 Bat Mountain fan___-____-___--___-__ 25 Shadow Mountain fan..______ 7 Fans east of Greenwater Range___ ______ 30 Geology.______________ 9 Fans in Greenwater Valley..-----_____. 32 Death Valley fans.__________--___-__- 32 Geomorpholo gy ______ 9 Characteristics of fans.._______-___-__- 38 Modern washes____. -

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY for FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type All Entries - Complete Applicable Sections) Rti^T Fl 1SP6

STATE: .Form Igd?6 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Uct. IV/^J NATIONAL PARK SERVICE California COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Shasta and Lassen INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) rti^T fl 1SP6 COMMON: Nobles' Emigrant Trail HS-1 AND/OR HISTORIC: Nobles' Trail (Fort Kearney, South Pass and Honey Lake Wagon Road) STREET AND NUMBER: M --"'' ^ * -X'"' '' J-- - ;/* ( ,: - "; ^ ;." ; r ^-v, % /'• - O1- - >,- ,•<•-,- , =••'"' CITY OR TOWN: / '-' j- ,. " ,-, ,, , CONG RESSIONAL DISTRICT: Lassen Volcanic National Park S econd STATE: CODE COUN TY: CODE California 06 Shaj3ta and Lassen 089/035 :. : ; STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check?ATE,G SOne)R \ OWNERSHIP SIAIU3 T0 THE p UBL|c gf] District Q Building [ig Public Public Acquisition: [ | Occupied Yes: : : -Z Q Site | | Structure | | Private Q In Process PT"1 Unoccupied | | Restricted 0 [~~| Object Qj Both f~| Being Consider)sd Q Preservation work [X] Unrestricted in progress [~~] No u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) | | Agricultural jj£] Government [X] Park | | Transportation | | Comments h- I | Commercial Q2 Industrial [~~| Private Residence | | Other (SpeciM »/> Q Educational Q Military [~1 Religious ;; /. z [^Entertainment Q Museum f"| Scientific UJ STATE: »/> National Park Service REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) SIr REET AND NUMBER: Western Region l^50 Golden Gate Avenue Cl TY OR TOWN: SIPATE: CODE San Francisco California Ub V BliBsi^iiiiBHIiiMMIiBlilBl^isMiM^Ml Illlllillliil^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: SIPATE: CODE Lassen Volcanic National Park California Ob toM^ TITLE OF SURVEY: The National Survey of Historic '&&& s^n^lt^J^aglix "Overland Migrations West of the Mississippi" TI AsX -X^ ENT^Y*"NUMBER o DATE OF SURVEY: 1959 [X] Federal Q State / ^yl County | _ | LocoilP' ^k X3 Z DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: t) •j? in C OAHP, WASO c/> rj V?\ m STREET AND NUMBER: 'l - i H~*~! ^|T"-, r £;. -

Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the many citizens, staff, and community groups who provided extensive input for the development of this Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan. The project was a true community effort, anticipating that this plan will meet the needs and desires of all residents of our growing County. SHASTA COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Glenn Hawes, Chair David Kehoe Les Baugh Leonard Moty Linda Hartman PROJECT ADVISORY COMMITTEE Terry Hanson, City of Redding Jim Milestone, National Park Service Heidi Horvitz, California State Parks Kim Niemer, City of Redding Chantz Joyce, Stewardship Council Minnie Sagar, Shasta County Public Health Bill Kuntz, Bureau of Land Management Brian Sindt, McConnell Foundation Jessica Lugo, City of Shasta Lake John Stokes, City of Anderson Cindy Luzietti, U.S. Forest Service SHASTA COUNTY STAFF Larry Lees, County Administrator Russ Mull, Department of Resource Management Director Richard Simon, Department of Resource Management Assistant Director Shiloe Braxton, Community Education Specialist CONSULTANT TEAM MIG, Inc. 815 SW 2nd Avenue, Suite 200 Portland, Oregon 97204 503.297.1005 www.migcom.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Plan Purpose 1 Benefits of Parks and Recreation 2 Plan Process 4 Public Involvement 5 Plan Organization 6 2. Existing Conditions ................................................................................ 7 Planning Area 7 Community Profile 8 Existing Resources 14 3. -

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest Welcome The following list of recreation activities are avail- able in the Hat Creek Recreation Area. For more detailed information please stop by the Old Station Visitor Information Center, open April - December, or our District Office located in Fall River Mills. Give Hat Creek Rim Overlook - Nearly 1 million years us a call year-around Mon.- Fri. at (530) 336-5521. ago, active faulting gradually dropped a block of Enjoy your visit to this very interesting country. the Earth’s crust (now Hat Creek Valley) 1,000 feet below the top of the Hat Creek Rim, leaving behind Subway Cave - See an underground cave formed this large fault scarp. This fault system is still “alive by flowing lava. Located just off Highway 89, 1/4 and cracking”. mile north of Old Station junction with Highway 44. The lava tube tour is self guided and the walk is A heritage of the Hat Creek area’s past, it offers mag- 1/3 mile long. Bring a lantern or strong flashlight nificent views of Hat Creek Valley, Lassen Peak, as the cave is not lighted. Sturdy Shoes and a light Burney Mountain, and, further away, Mt. Shasta. jacket are advisable. Subway Cave is closed during the winter months. Fault Hat Creek Rim Fault Scarp Vertical movement Hat Creek V Cross Section of a Lava Tube along this fault system alley dropped this block of earth into its present position Spattercone Trail - Walk a nature trail where volca- nic spattercones and other interesting geologic fea- tures may be seen. -

Geologic Gems of California's State Parks

STATE OF CALIFORNIA – EDMUND G. BROWN JR., GOVERNOR NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY – JOHN LAIRD, SECRETARY CALIFORNIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION – LISA MANGAT, DIRECTOR JOHN D. PARRISH, Ph.D., STATE GEOLOGIST DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION – DAVID BUNN, DIRECTOR PLATE 1 The rugged cliffs of Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park are composed of some of California’s Bio-regions the most tortured, twisted, and mobile rocks of the North American continent. The California’s Geomorphic Provinces rocks are mostly buried beneath soils and covered by vigorous redwood forests, which thrive in a climate famous for summer fog and powerful winter storms. The rocks only reveal themselves in steep stream banks, along road and trail cut banks, along the precipitous coastal cliffs and offshore in the form of towering rock monuments or sea stacks. (Photograph by CalTrans staff.) Few of California’s State parks display impressive monoliths adorned like a Patrick’s Point State Park displays a snapshot of geologic processes that have castle with towering spires and few permit rock climbing. Castle Crags State shaped the face of western North America, and that continue today. The rocks Park is an exception. The scenic beauty is best enjoyed from a distant exposed in the seacliffs and offshore represent dynamic interplay between the vantage point where one can see the range of surrounding landforms. The The Klamath Mountains consist of several rugged ranges and deep canyons. Klamath/North Coast Bioregion San Joaquin Valley Colorado Desert subducting oceanic tectonic plate (Gorda Plate) and the continental North American monolith and its surroundings are a microcosm of the Klamath Mountains The mountains reach elevations of 6,000 to 8,000 feet. -

Federal Register/Vol. 68, No. 65/Friday, April 4, 2003/Notices

16548 Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 65 / Friday, April 4, 2003 / Notices The segregative effect associated with Statement, but was included and the National Park Service (NPS) the application terminated March 19, analyzed, along with 4 additional acquiring the land on which the lake 2000, in accordance with the notice alternatives, in the Final Supplemental sits. The lake was built by Sifford to published as FR Doc. 00–3267 in the Environmental Impact Statement. The provide scenic benefits and recreational Federal Register (65 FR 7057–8) dated full range of foreseeable environmental opportunities to guests at the nearby February 11, 2000. consequences was assessed, and Drakesbad Guest Ranch, which Sifford Dated: January 21, 2003. appropriate mitigating measures were owned. Drakesbad Guest Ranch is over Howard A. Lemm, identified. 100 years old and is still in operation to The Record of Decision includes a this day. It is owned by the National Acting Deputy State Director, Division of statement of the decision made, Resources. Park Service and is located within the synopses of other alternatives boundaries of Lassen Volcanic National [FR Doc. 03–8170 Filed 4–3–03; 8:45 am] considered, the basis for the decision, a Park. Drakesbad is operated by the BILLING CODE 4310–$$–P description of the environmentally Park’s concessioner, California Guest preferable alternative, a finding Services. Drakesbad, with nearby Dream DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR regarding impairment of park resources Lake, is a popular destination and has and values, a listing of measures to been visited by many generations of National Park Service minimize environmental harm, an families. -

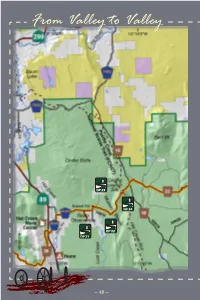

From Valley to Valley

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

Sulphur Works Is Believed to Have Been the Main Vent for Mount Tehama, a Stratovolcano That Started Erupting About 600,000 Years Ago

Junior Park Explorer Lassen Volcanic National Park Mystery of Mount Tehama Imagine you are standing almost a mile deep inside a stratovolcano. Well, 400,000 years ago you would have been! The area around Sulphur Works is believed to have been the main vent for Mount Tehama, a stratovolcano that started erupting about 600,000 years ago. By 400,000 years ago, it had reached its full height of 11,500 feet. Look around you in a full circle. Can you spot the mountains pictured below? They are all remnants (left over bits) of Mount Tehama. Remnant 1 – Brokeoff Mountain Remnant 2 – Mount Diller Remnant 3 – Pilot Pinnacle Remnant – Mount Conard Activity 1 - See if you can find these remnants on your park map. Trace a circle from one mountain to the next to outline the footprint of Mount Tehama. Be sure to include Little Hot Springs Valley inside the footprint. Activity 2 - Use the diagram on the next page to reconstruct Mount Tehama. Connect point A to point B, A to C, A to D, A to E, & A to F, individually. Can you see Mount Tehama in your imagination? Color in the mountain if you wish. Activity 3 - Another way to reconstruct Mount Tehama is as a view from down in the Sacramento Valley. On the next page, check out how the skyline of Lassen Volcanic National Park looks today, looking east from near Redding. Can you draw what the skyline might have looked like when Mount Tehama was at its full height of 11,500 feet, 400,000 years ago? Use the graph on the next page. -

Drakesbad Guest Ranch Plumas CA Property Name County State

NFS Form 10-900a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section Page SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 03001062 Date Listed: 10/22/2003 Drakesbad Guest Ranch Plumas CA Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. / Signatur the Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Functions: The Historic Functions should be amended to include the following categories: Domestic/Hotel; Domestic/Camp; Recreation/Outdoor Recreation; Agriculture/Agricultural Fields; and Landscape/Natural feature. These revisions were confirmed with the NFS FPO office. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 1 0-900 OMB No. 1 024-001 8 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior , National Park Service \(} v> NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Drakesbad Guest Ranch other name/site number: Drake's Baths; Drakesbad Resort; Hot Springs Valley 2. Location street & number: N/A not for publication: n/a vicinity: Head of Warner Creek Valley, Lassen Volcanic National Park city /town: Chester state: California code: CA county: Plumas code: 063 zip code: 96020 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professionjiiemiirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.