V. Water Quality 5.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the many citizens, staff, and community groups who provided extensive input for the development of this Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan. The project was a true community effort, anticipating that this plan will meet the needs and desires of all residents of our growing County. SHASTA COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Glenn Hawes, Chair David Kehoe Les Baugh Leonard Moty Linda Hartman PROJECT ADVISORY COMMITTEE Terry Hanson, City of Redding Jim Milestone, National Park Service Heidi Horvitz, California State Parks Kim Niemer, City of Redding Chantz Joyce, Stewardship Council Minnie Sagar, Shasta County Public Health Bill Kuntz, Bureau of Land Management Brian Sindt, McConnell Foundation Jessica Lugo, City of Shasta Lake John Stokes, City of Anderson Cindy Luzietti, U.S. Forest Service SHASTA COUNTY STAFF Larry Lees, County Administrator Russ Mull, Department of Resource Management Director Richard Simon, Department of Resource Management Assistant Director Shiloe Braxton, Community Education Specialist CONSULTANT TEAM MIG, Inc. 815 SW 2nd Avenue, Suite 200 Portland, Oregon 97204 503.297.1005 www.migcom.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Plan Purpose 1 Benefits of Parks and Recreation 2 Plan Process 4 Public Involvement 5 Plan Organization 6 2. Existing Conditions ................................................................................ 7 Planning Area 7 Community Profile 8 Existing Resources 14 3. -

Aspects of Pit River Phonology

ASPECTS OF PIT RIVER PHONOLOGY Bruce E. Nevin A DISSERTATION in Linguistics Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1998 _____________________________ Supervisor of Dissertation _____________________________ Graduate Group Chairperson iii iv To the Pit River people In memory of Yámá·litwí·daá Dísdí sí·sá·dumá má céá suwí tús dit·é·wi, amxágam táxábáà tól·ím dáx cú wíc stíjéuwí?à Qa ßís ßú wóá dis·i ßuwá·géá ß tyánuwí,á toljana winá·ji·wíní. iii iv Abstract Aspects of Pit River Phonology Bruce Nevin Eugene Buckley Until recently, it has seemed that the Pit River language (“Achumawi”) was reasonably well documented by de Angulo & Freeland (1930), Uldall (1933), and Olmsted (1956, 1957, 1959, 1964, 1966). My own fieldwork in 1970-74 disclosed fundamental inadequacies of these publications, as reported in Nevin (1991). We substantiate this finding, investigate its probable bases, and establish why my own data are not subject to the same difficulties. After this cautionary tale about the perils of restating a published grammar, we define a phonemic representation for utterances in the language and introduce Optimality Theory (OT). We then apply OT to a series of problems in the phonological patterning of the language: features of syllable codas, restrictions and alternations involving voiceless release and aspiration, and reduplicative morphology. Appendix A describes the physiology and phonetics of laryngeal phenomena in Pit River, especially epiglottal articulation that has in the past been improperly described as pharyngeal or involving the tongue radix (the feature RTR). -

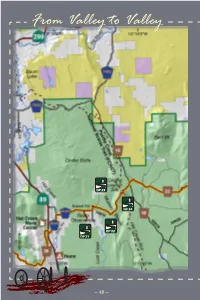

From Valley to Valley

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

Lessons in Bronze

LESSONS IN BRONZE Why Good History Matters Patricia Lord July 10, 2018 Thank you to the many local historians, activists, and leaders, who freely shared their knowledge, gave support, and made this paper possible. 2 In mid-March 2018, a plaque honoring the heroics of a man during one of the deadliest periods of Shasta County’s history was proposed. The plaque, containing only a few sentences, is one of the best examples of the need for the careful study of history. Titled “Pioneer Courage,” the plaque memorializes “... the rescue and protection from vigilante revenge on this ground of twelve innocent Yana First Nation people following the Allen-Jones pioneer family murders of 1864.” The bronze plaque attributes the salvation of the individuals to a man who owned a farm near the Sacramento River. Even though the text is presented as a straightforward account of an important but less known event from local history, conversations with community members and research reveals much more (Benda, 2018). The plaque has become an important example that can help clarify what ideals we should uphold, who we acknowledge, and what a vibrant community that values its history looks like. Most histories of the Allen-Jones massacres start from the same place, the murder of two women, though the murders are closer to the middle of the story than the start. On September 8, 1864, a woman by the name of Catherine Allen (née Boyes) (Janice, 2007) who lived just east of Millville was attacked and killed reportedly by two Native American men. Her four children were also attacked, though they all recovered. -

FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE a Master's Exhibition of Print Media

FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE A Master’s Exhibition of Print Media Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Art by © Jennifer Lee Tancreto 2015 Spring 2015 FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE A Master’s Exhibition by Jennifer Lee Tancreto Spring 2015 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: _________________________________ Eun K. Park, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE. _________________________________ _________________________________ Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A. Eileen M. Macdonald, M.F.A., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION To the women of my past and present who have shown me through example, friendship, and love, how to face life’s challenges with strength and grace. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people were instrumental in the process of my exhibition and thesis and I am grateful to each person who has made this journey possible. Thank you to the Department of Art and Art History for providing me with a rich community of artists and scholars. To my committee chair, Eileen Macdonald who has always given me support and encouragement. My success as a both a student and an instructor are because of her instruction and guidance. To Sheri Simons, who pushed me all they way to the end and whose temporary absence in these last weeks has been felt. -

Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Social Science Program Visitor Services Project Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study [Insert image here] OMB Control Number:1024-0224 Current Expiration Date: 8/31/2014 2 Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Lassen Volcanic National Park P.O. Box 100 Mineral, CA 96063 IN REPLY REFER TO: January/June 2012 Dear Visitor: Thank you for participating in this study. Our goal is to learn about the expectations, opinions, and interests of visitors to Lassen Volcanic National Park. This information will assist us in our efforts to better manage this park and to serve you. This questionnaire is only being given to a select number of visitors, so your participation is very important! It should only take about 20 minutes to complete. Please complete this questionnaire. Seal it in and return it to us in the postage paid envelope provided. If you have any questions, please contact Margaret Littlejohn, NPS VSP Director, Park Studies Unit, College of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 441139, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1139, phone: 208-885-7863, email: [email protected]. We appreciate your help. Sincerely, Darlene M. Koontz Superintendent Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study 3 DIRECTIONS At the end of your visit: 1. Please have the selected individual (at least 16 years old) complete this questionnaire. 2. Answer the questions carefully since each question is different. 3. For questions that use circles (O), please mark your answer by filling in the circle with black or blue ink. -

Ishi, the Last Wild Indian, 2001 Peabody Essex Museum David P

Ishi, the Last Wild Indian, 2001 Peabody Essex Museum David P. Bradley, White Earth Ojibwe (1954 - ) Salem in History, 2006 Ishi, the Last Wild Indian, 2001 David P. Bradley, White Earth Ojibwe (1954 - ) Santa Fe, N.M. Mixed Media on Board Gift of Mr. & Mrs. James N. Krebs, 2001 E301825 H I S T O R I C A L C O N T E X T Ishi (c.1860-1916) was the last living member of the Yahi tribe, the southernmost tribe of the Yana people who inhabited northern California and the Sacramento Valley.The California gold rush and influx of foreign- ers contributed to the quick demise of the Yana tribes through conflict and disease. Apparently the last surviving Yahi, Ishi journeyed into white society, and was brought to the Museum of Anthropology in San Francisco by anthropologist Alfred Lewis Kroeber. He worked as both a janitor and as a “living exhibit,” making arrowheads in front of paying museum visitors and helping researchers record the Yana language.This survivor did not divulge information about his deceased family, however, and he did not even reveal his own name. “Ishi” means “man” in Yana. The mysterious person known as Ishi did in 1916, a victim of tuberculosis, which was foreign to the Yahi. Rumors spread that Ishi’s brain had been preserved after his death, but it wasn’t until 1999 that his pickled brain was found in a Smithsonian museum warehouse.This prompted much controversy and political debate.The Smithsonian agreed to return Ishi’s brain to surviving Native American tribes closely related to the Yahi, and it was buried with Ishi’s body in 2000. -

Bureau of Indian Affairs

New Land Old Tribe Region Tribal Area Description Code Code Code Eastern 001 001 001 CHEROKEE (EASTERN BAND QUALLA BOUNDARY) - NC 002 002 CATAWBA NATION - SC X003 003 003 CORNPLANTER 004 004 004 SENECA NATION (ALLEGHENY) - NY 005 005 005 CATTARAUGUS 006 006 006 ONONDAGA NATION - NY 007 007 007 MOHAWK (ST. REGIS BAND) - NY 008 008 008 SENECA (TONAWANDA BAND) - NY 009 009 009 TUSCARORA NATION - NY X010 010 010 OIL SPRINGS 011 011 011 ONEIDA NATION - NY 012 012 SENECA NATION - NY 012 BIG CYPRESS SCHOOL-SEMINOLE 013 013 013 CAYUGA NATION - NY 014 014 014 PASSAMAQUODDY - ME 015 IROQUOIS A014 016 016 PASSAMAQUODDY TRIBE INDIAN TOWNSHIP B014 017 017 PASSAMAQUODDY TRIBE PLEASANT POINT 018 018 018 PENOBSCOT - ME 019 019 019 MALISEET (HOULTON BAND) -- ME 020 020 020 MASHANTUCKET PEQUOT - CT SEMINOLE (DANIA, BIG CYPRESS, BRIGHTON, HOLLYWOOD, 021 021 021 TAMPA) - FL A021 022 022 SEMINOLE (BRIGHTON) B021 023 023 SEMINOLE (DANIA) 024 024 TAMIANI TRAIL GROUP (INGRAHAM BILLIE) 025 CODE NOT YET ASSIGNED 026 026 026 MICCOSUKEE - FL 027 027 027 NARRAGANSETT - RI 028 028 043 CREEK (POARCH BAND) - AL 029 029 CODE NOT YET ASSIGNED 030 030 030 WAMPANOAG (GAY HEAD - AQUINNAH) - MA 031 031 MICMAC (AROOSTOOK BAND) - ME 032 032 CATAWBA NATION - SC 033 033 MOHEGAN - CT 034 034 CHOCTAW (JENA BAND) - LA 035 039 035 THROUGH 039 CODES NOT YET ASSIGNED 040 040 040 MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW 041 099 041 THROUGH 099 CODES NOT YET ASSIGNED X100 100 MISCELLANEOUS - WA 101 101 CONFEDERATED TRIBES (COLVILLE) - WA 102 102 SPOKANE - WA 103 103 KALISPEL COMMUNITY - WA 104 104 CODE NOT -

California-Nevada Region

Research Guides for both historic and modern Native Communities relating to records held at the National Archives California Nevada Introduction Page Introduction Page Historic Native Communities Historic Native Communities Modern Native Communities Modern Native Communities Sample Document Beginning of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the U.S. Government and the Kahwea, San Luis Rey, and Cocomcahra Indians. Signed at the Village of Temecula, California, 1/5/1852. National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/55030733 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities California Native Communities To perform a search of more general records of California’s Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog, use Advanced Search. Enter California in the search box and 75 in the Record Group box (Bureau of Indian Affairs). There are several great resources available for general information and material for kids about the Native People of California, such as the Native Languages and National Museum of the American Indian websites. Type California into the main search box for both. Related state agencies and universities may also hold records or information about these communities. Examples might include the California State Archives, the Online Archive of California, and the University of California Santa Barbara Native American Collections. Historic California Native Communities Federally Recognized Native Communities in California (2018) Sample Document Map of Selected Site for Indian Reservation in Mendocino County, California, 7/30/1856. National Archives: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/50926106 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities Historic California Native Communities For a map of historic language areas in California, see Native Languages. -

BO-01-2006-0022 In-State Residency for Aboriginal Residents

Blue Mountain Community College Administrative Procedure Procedure Title: In-State Residency Status for Aboriginal Residents Procedure Number: 01-2006-0022 Board Policy Reference: I.B. Accountable Administrator: Vice President Student Affairs Position responsible for updating: Vice President Student Affairs Original Date: August 10, 2005 Date Approved by Cabinet: 08-29-06 Authorizing Signature: Signed original on file Dated: 08-31-06 Date Posted on Web: 09-06-06 Revised: Reviewed: ______________________________________________________________________ Purpose/Principle/Definitions: Blue Mountain Community College, in a process to enhance student support while providing a premier learning environment, sets forth the following procedure to allow the waiver of out-of-state tuition fees to aboriginal residents as defined below. Guidelines:Students who are enrolled members of federally recognized tribes of Oregon or who are enrolled members of a Native American tribe which had traditional and customary tribal boundaries that included parts of the state of Oregon or which had ceded or reserved lands within the state of Oregon shall be assessed resident tuition regardless of their state of residence. For purposes of this rule, the federally recognized tribes of Oregon are: (a) Burns Paiute Tribe; (b) Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw; (c) Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon; (d) Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians of Oregon; (e) Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation; (f) Confederated Tribes -

GOVERNING BODIES of Federally RECOGNIZED INDIAN GROUPS

Goverrllng Bcxliesof Federallyc R~l IndianGroups (ExchKlingAlaska) GOVERNING BODIES OF FEDERAllY RECOGNIZED INDIAN GROUPS (Inquiries about Alaska Natives should be directed to the Bureau's Juneau Area Office, Box 3-8000, Juneau, Alaska 99802) GOVERNING BODY AND TITLE OF PRESIDING OFF!CER ADDRESS Absentee-Shawnee Business Box 1747 Committee, Shawnee, Oklahoma 74801 Chairman Acoma Pueblo Council, Box 309 Governor Acomita, New Mexico 87049 Agua Caliente Tribal Council, P.O. Box 2245 Chairman Palm Springs, California 92262 Ak-Chin Indian Community Council, Route 1, Box 12 Chairman Maricopa, Arizona 85239 Alabama-Quassarte Creek Tribal Town, Route 2, Box 142 Chief Wetumka, Oklahoma 74883 Alturas General Council, c/o Central California Agency Spokesman Bureau of Indian Affairs Box 15740 Sacramento, California 95813 Apache Business Committee, Box 1220 Chairman Anadarko, Oklahoma 73005 Arapahoe Business Council Arapahoe, Wyoming 82510 (Wind River), Chairman Augustine Band of Mission Indians, c/o Southern California Agency Representative Bureau of Indian Affairs 5750 Division St. Riverside, California 92506 Bad River Tribal Council, Route 2 Chairman Ashland, Wisconsin 54806 Barona General Council, 1095 Barona Rd. Chairman Lakeside, California 92040 Bay Mills Executive Council, Route 1 President Brimley, Michigan 49715 Benton (See Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute) 1 GOVERNING BODY AND TITLE OF PRESIDING OFFICER ADDRESS Berry Creek Rancheria C/O Central California Agency Bureau of Indian Affairs Box 15740 Sacramento, California 95813 Big Bend Rancheria, c/o -

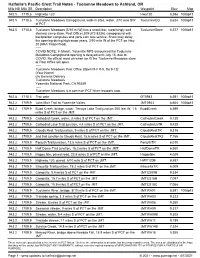

Halfmile's Pacific Crest Trail Notes

Halfmile's Pacific Crest Trail Notes - Tuolumne Meadows to Ashland, OR Mile NB Mile SB Description Waypoint Elev Map 942.5 1710.6 Highway 120 Hwy120 8,596 1008p15 942.5 1710.6 Tuolumne Meadows Campground, walk-in sites, water, 3/10 mile SW TuolumneCG 8,624 1008p15 of PCT. 942.5 1710.6 Tuolumne Meadows [3/10 mi W] has a snack bar, surprisingly well TuolumneStore 8,577 1008p15 stocked camp store, Post Office [209-372-8236], campground with backpacker campsites and yarts.com bus service. Snow may delay the opening during high snow years. 3/10 mile W of the PCT on Hwy 20 [AKA Tioga Road]. ----- COVID NOTE: In March, Yosemite NPS announced the Tuolumne Meadows Campground opening is delayed until July 15, due to COVID. No official word on when (or if) the Tuolumne Meadows store or Post Office will open. ----- Tuolumne Meadows Post Office [Open M-F 9-5, Sa 9-12]: (Your Name) c/o General Delivery Tuolumne Meadows Yosemite National Park, CA 95389 ----- Tuolumne Meadows is a common PCT hiker resupply stop. 942.8 1710.3 Trail gate GT0943 8,591 1008p15 943.2 1709.9 John Muir Trail to Yosemite Valley. JMT0943 8,604 1008p15 943.2 1709.9 Budd Creek, bridge, water, Tenaya Lake Trail junction 200 feet W, 1.5 BuddCreek 8,599 miles S of PCT on the JMT. 943.2 1709.9 Cathedral Creek, water, 3 miles S of PCT on the JMT. CathedralCreek 9,135 943.2 1709.9 Cathedral Lake Trail junction, 4.4 miles S of PCT on the JMT.