Bistorical Society Quarterly DIRECTOR JOHN TOWNLEY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perilous Last Leg of the Oregon Trail Down the Columbia River

Emigrant Lake County Park California National Historic Trail Hugo Neighborhood Association and Historical Society Jackson County Parks National Park Service The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon The perilous last leg of the Oregon Trail down the “Father and Uncle Jesse, seeing their children drowning, were seized with ‘ Columbia River rapids took lives, including the sons frenzy, and dropping their oars, sprang from their seats and were about to make a desperate attempt to swim to them. But Mother and Aunt Cynthia of Jesse and Lindsay Applegate in 1843. The Applegate cried out, ‘Men, don't quit your oars! If you do, we'll all be lost!’” brothers along with others vowed to look for an all- -Lindsay Applegate’s son Jesse land route into Oregon from Idaho for future settlers. “Our hearts are broken. As soon as our families are settled and time can be spared we must look for another way that avoids the river.” -Lindsay Applegate In 1846 Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and 13 others from near Dallas, Oregon, headed south following old trapper trails into a remote region of Oregon Country. An Umpqua Indian showed them a foot trail that crossed the Calapooya Mountains, then on to Umpqua Valley, Canyon Creek, and the Rogue Valley. They next turned east and went over the Cascade Mountains to the Klamath Basin. The party devised pathways through canyons and mountain passes, connecting the trail south from the Willamette Valley with the existing California Trail to Fort Hall, Idaho. In August 1846, the first emigrants to trek the new southern road left Fort Hall. -

Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the many citizens, staff, and community groups who provided extensive input for the development of this Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan. The project was a true community effort, anticipating that this plan will meet the needs and desires of all residents of our growing County. SHASTA COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Glenn Hawes, Chair David Kehoe Les Baugh Leonard Moty Linda Hartman PROJECT ADVISORY COMMITTEE Terry Hanson, City of Redding Jim Milestone, National Park Service Heidi Horvitz, California State Parks Kim Niemer, City of Redding Chantz Joyce, Stewardship Council Minnie Sagar, Shasta County Public Health Bill Kuntz, Bureau of Land Management Brian Sindt, McConnell Foundation Jessica Lugo, City of Shasta Lake John Stokes, City of Anderson Cindy Luzietti, U.S. Forest Service SHASTA COUNTY STAFF Larry Lees, County Administrator Russ Mull, Department of Resource Management Director Richard Simon, Department of Resource Management Assistant Director Shiloe Braxton, Community Education Specialist CONSULTANT TEAM MIG, Inc. 815 SW 2nd Avenue, Suite 200 Portland, Oregon 97204 503.297.1005 www.migcom.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Plan Purpose 1 Benefits of Parks and Recreation 2 Plan Process 4 Public Involvement 5 Plan Organization 6 2. Existing Conditions ................................................................................ 7 Planning Area 7 Community Profile 8 Existing Resources 14 3. -

El Mustang, January 14, 1955

VOLUME 15, NUMBER 10 SAN LUIS OBISPO, CALIFORNIA FRIDAY, JANUARY 14, 1955 Seven Men Join Faculty Pioneer Era Of 1890's Seven now Instructors have jolntid the Cal Poly faculty, ac Brings Vision of Poly cording to l’ roaldant Julian A, Mcl’hfu, by Bob Flood THU Is ths fleet In s ssrlM sf srtlrlsi os tho tsrlr hlilsrr if Csl Pslr whisk Assuming their new dutto* at Kl Millions will publloh dsrlng tho ossilnf wooko, . the beginning of the winter quar Moot sf tho In Ur SI tl Ion totherH br Mloo Msresrot Chsoo, who ossit Is Col ter were Jack L. Albright, dairy Pslr Is IMS ond woo omplorod hr tko oolloto fsr s»or IT posio. huibandryi Dr. LuVerno Bucjjr, At tne end of the 18th century, ahortlv before Cal Polv animal huibandryi Dr. Dali waa established by the state legislature, San Luis Obispo was littu, viterlnury iclincii Lisle R. a small town about 4,000, not much larger than Cal Poly’a Green, loll iclin ci; John Q. Palm- present enrollment. Automobiles were unknown and High quilt, agricultural engineering, Frit/. H. Olien, wilding, and MorrTi way 101 was little more than a layer of dust in summer and P, Taylor, phyilci. ‘ (mud In winter, Albright, formerly In charge of A• Poly atudent, facing tha thf Adohr Parmi show herd, grad* Campus Club* Sign transportation conditions of those uated from Cal Poly In 1068 and days would not have gotten far received hie maeter of science de on his wseksnd trip horn# to I.os gree from Waihlngton State col- Soon For El Rodeo Angelos, or ths Ran Francisco lege In June. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

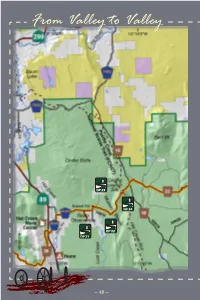

From Valley to Valley

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

1 Applegate Emigrants to Oregon in 1843

http://www.oregonpioneers.com/1843.htm 1 Applegate Emigrants to Oregon In 1843 Albert APPLEGATE was actually born in the Oregon Territory December 6, 1843 at the abandoned Willamette Mission where his parents, Charles Applegate and Melinda Miller, wintered. While not enumerated as an emigrant of that year he can certainly be considered a pioneer of that time period. Albert married January 17, 1869 at Drain, Douglas County, Oregon to Nancy Johnson. His adult years were spent in the Douglas Co area. It was here that he raised his family: Mercy D. (1870), Nellie M. (1871), Jesse Grant (1873), Fred (1875) and Lulu (1878). Albert died March 18, 1888. After his death his wife, Nancy Johnson Applegate, married James Shelley and was residing at Eugene, Lane County, Oregon in the 1900 census. Alexander McClelland APPLEGATE was born Mar 11, 1838 in St. Clair County, Missouri, the son of Jesse Applegate and Cynthia Parker. He was five years old at the time the Applegates crossed the plains to Oregon in 1843. With his family he settled in Polk County in 1844 and in 1850 was living in Benton County. By 1860 the family had moved to Yoncalla, Douglas County, OR. Shortly after arriving, Alex went to the Idaho gold fields with Henry Lane, son of the famous Joseph Lane, who lived in nearby Roseburg. He and Henry and Alex's cousin John Applegate enjoyed playing the fiddle together. They often played at dances as "The Fiddlers Three." Henry Lane had been a suitor of Alex’s cousin, Harriet. When the young men received the news in Idaho of the death of Harriet Applegate, Alex wrote home: "Your dream that some of us who parted last spring would no longer meet again in this life has been fulfilled. -

PETER LASSEN NEW EVIDENCE FOUND News from the President

Volume 35, Number 2 Red Bluff, California November/December 2015 PETER LASSEN News from the President NEW EVIDENCE FOUND The Society is very excited to let you know that Please join us on Thursday, November we have been able to obtain a complete listing of 12th, at 7 pm in the West Room of the Red all interred at both Oak Hill and St. Mary's Bluff Community Center for a new cemeteries on our web page. It lists names, presentation by historian Dave Freeman on the location of grave, birth, death and interment dates works of Peter Lassen as he developed his and will be a very valuable tool for those rancho on the banks of Deer Creek near the researchers attempting to find this information, present-day town of Vina. especially if they visit the cemetery on a weekend A self-proclaimed “amateur” or after hours. Go to our home page archaeologist, Freeman has a impressive body of www.tcghsoc.org and click on "Up Dated". If you work and is a columnist for the Colusi County need a map click on "Cemeteries" then on "Red Historical Society. This spring he was invited to Bluff Oak Hill". speak about his continuing research on Lassen at When you visit our web page check out and the California-Nevada Chapter OCTA (Oregon- download the Tehama County Museum Flyer. California Trails Assoc.) symposium. This is a helpful flyer that has a list of nine Dave is known for his uniting of records museums in Tehama County, their address and research with extensive boots-on-the-ground contact information. -

FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE a Master's Exhibition of Print Media

FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE A Master’s Exhibition of Print Media Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Art by © Jennifer Lee Tancreto 2015 Spring 2015 FROM HERE YOU CAN SEE A Master’s Exhibition by Jennifer Lee Tancreto Spring 2015 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: _________________________________ Eun K. Park, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE. _________________________________ _________________________________ Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A. Eileen M. Macdonald, M.F.A., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION To the women of my past and present who have shown me through example, friendship, and love, how to face life’s challenges with strength and grace. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people were instrumental in the process of my exhibition and thesis and I am grateful to each person who has made this journey possible. Thank you to the Department of Art and Art History for providing me with a rich community of artists and scholars. To my committee chair, Eileen Macdonald who has always given me support and encouragement. My success as a both a student and an instructor are because of her instruction and guidance. To Sheri Simons, who pushed me all they way to the end and whose temporary absence in these last weeks has been felt. -

Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Social Science Program Visitor Services Project Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study [Insert image here] OMB Control Number:1024-0224 Current Expiration Date: 8/31/2014 2 Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Lassen Volcanic National Park P.O. Box 100 Mineral, CA 96063 IN REPLY REFER TO: January/June 2012 Dear Visitor: Thank you for participating in this study. Our goal is to learn about the expectations, opinions, and interests of visitors to Lassen Volcanic National Park. This information will assist us in our efforts to better manage this park and to serve you. This questionnaire is only being given to a select number of visitors, so your participation is very important! It should only take about 20 minutes to complete. Please complete this questionnaire. Seal it in and return it to us in the postage paid envelope provided. If you have any questions, please contact Margaret Littlejohn, NPS VSP Director, Park Studies Unit, College of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 441139, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1139, phone: 208-885-7863, email: [email protected]. We appreciate your help. Sincerely, Darlene M. Koontz Superintendent Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study 3 DIRECTIONS At the end of your visit: 1. Please have the selected individual (at least 16 years old) complete this questionnaire. 2. Answer the questions carefully since each question is different. 3. For questions that use circles (O), please mark your answer by filling in the circle with black or blue ink. -

Grandma Rock Emigrants

Manzanita Rest Area California National Historic Trail Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians National Park Service Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Hugo Neighborhood Association Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians and Historical Society The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon The perilous last leg of the Oregon Trail down the ‘ Columbia River rapids took lives, including the sons of Jesse and Lindsay Applegate in 1843. The Applegate brothers and others vowed to look for an all-land route into Oregon from Fort Hall (in present-day Idaho) for future settlers. Additionally, It was important to have a way by such we could leave the country without running the gauntlet of the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s forts and falling prey to Indians which were under British influence. -Lindsay Applegate In 1846 Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and 13 others Father and Uncle Jesse, seeing their children from near Dallas, Oregon, headed south following old drowning, were seized with frenzy, and dropping their oars, sprang from their seats trapper trails into a remote region of Oregon Country. and were about to make a desperate attempt First they crossed the Calapooya Mountains, then the to swim to them. But Mother and Aunt Cynthia Umpqua Valley, Canyon Creek, and the Rogue Valley. cried out, ‘Men, don't quit your oars! If you do, we'll all be lost!’ They next turned east and went over the Cascade -Lindsay Applegate’s son Jesse Mountains to the lakes of the Klamath Basin. The party detoured around the lakes and located the Our hearts are broken. -

Peter Lassen Finally Vindicated?

Volume 33, Number 1 Red Bluff, California September/October 2013 …Although the distance is PETER LASSEN FINALLY much greater [on the Lassen Trail]…and VINDICATED? some of the emigrants were much longer in getting in, I cannot but think it a fortunate circumstance they did so [take the Lassen After reading many Trail] for the loss of property would have disparaging comments over the years about been much greater on the old trail [Carson or our not-so-venerated pioneer, Peter Lassen, Truckee], as the grass would have been and his “horrendous” Lassen Trail, we now eaten off long before they arrived. have a book that claims to set the record The author contrasts this statement straight and present a more balanced with one by Simon Doyle, one of the viewpoint on old “Uncle Peter.” The book is unhappy emigrants (exactly as written): entitled Legendary Truths, Peter Lassen and At the [Lassen’s] Ranch everything is His Gold Rush Trail in Fact and Fable, by a regular jam. Men going hither and yon, Ken Johnston, 2012. Mr. Johnston was a whiskey, some meals victuals, others to get park ranger naturalist/interpreter at Lassen the meal without buying for they have National Park in the 1970s and has been nothing to buy with, some to pore forth researching Lassen ever since, in his career curses and abuse upon Lassen for his as an educator. His bibliography includes rascally deceitfulness in making the 180 items! Northern road [Lassen Trail]. In this all The major puzzle regarding Lassen is hands join and the Old Dutchman is in that while he was respected and many eminent danger of losing his life and makes geographical locations have been named for himself as humble as possible. -

The End of the Line Changes to the Trail California National Historie

California National Historie Trail The California Nat ional Historie Trai l spans 2,000 miles across the United States. lt brought em igrants, gold-seekers, merchants, and others west to California in the l 800s. The Bu reau of Land Management in California manages four segments, nearly 140-miles of the trail, the Appl egate, the Lassen, the Nobles, and the Yreka . Set ee n 1841 and 1869, more than 250,000 emigrants traversed the Cal ifornia Trail. Lured by gold, farmland and a promise of paradise in California, mid l 9th century emigrants used the Ca lifornia a 1onal Historie Tra il for a migration route to the west. umerous routes emerged in attempts to create the best available course. Today, this t rail offer s auto ouring, educa ional programs and vi siter centers to present-day gold seekers arid explorers. ln 1992, Congress designated the Californ ia Trail system as a National Historie Trail. ln 2000, it also became part of the ln April of 1852, William H. Nobles Bureau of Land anagement's system of National Conservation Lands. This is a 36 million-acre collection of treasured landscapes conserved by the Bureau of La nd Management. Find out more at www bl gov/ programs/ national Z:6Z:E-LSZ: (OES) placed a notice in the Shasta Courier Changes to the Trail conservation-lands. Of: L96 V'J 'a ll!Auesns announcing a meeting in Shasta +aaJ+S Mopay+eaM S L L The original route runs from Black Roc Springs, wnasnl/\l 1e::> !JO+S! H uasse1 Ala!OOS 1eo!JOlS!H A}uno~ uasse1 City, where he would reveal his newly Nevada to Shasta City, California and as used mainly w+y ·xapu1/ 0Ael/Ao5·sdu-MMM discovered wagon route, which later from 1852 to 1869.