National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY for FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type All Entries - Complete Applicable Sections) Rti^T Fl 1SP6

STATE: .Form Igd?6 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Uct. IV/^J NATIONAL PARK SERVICE California COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Shasta and Lassen INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) rti^T fl 1SP6 COMMON: Nobles' Emigrant Trail HS-1 AND/OR HISTORIC: Nobles' Trail (Fort Kearney, South Pass and Honey Lake Wagon Road) STREET AND NUMBER: M --"'' ^ * -X'"' '' J-- - ;/* ( ,: - "; ^ ;." ; r ^-v, % /'• - O1- - >,- ,•<•-,- , =••'"' CITY OR TOWN: / '-' j- ,. " ,-, ,, , CONG RESSIONAL DISTRICT: Lassen Volcanic National Park S econd STATE: CODE COUN TY: CODE California 06 Shaj3ta and Lassen 089/035 :. : ; STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check?ATE,G SOne)R \ OWNERSHIP SIAIU3 T0 THE p UBL|c gf] District Q Building [ig Public Public Acquisition: [ | Occupied Yes: : : -Z Q Site | | Structure | | Private Q In Process PT"1 Unoccupied | | Restricted 0 [~~| Object Qj Both f~| Being Consider)sd Q Preservation work [X] Unrestricted in progress [~~] No u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) | | Agricultural jj£] Government [X] Park | | Transportation | | Comments h- I | Commercial Q2 Industrial [~~| Private Residence | | Other (SpeciM »/> Q Educational Q Military [~1 Religious ;; /. z [^Entertainment Q Museum f"| Scientific UJ STATE: »/> National Park Service REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) SIr REET AND NUMBER: Western Region l^50 Golden Gate Avenue Cl TY OR TOWN: SIPATE: CODE San Francisco California Ub V BliBsi^iiiiBHIiiMMIiBlilBl^isMiM^Ml Illlllillliil^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: SIPATE: CODE Lassen Volcanic National Park California Ob toM^ TITLE OF SURVEY: The National Survey of Historic '&&& s^n^lt^J^aglix "Overland Migrations West of the Mississippi" TI AsX -X^ ENT^Y*"NUMBER o DATE OF SURVEY: 1959 [X] Federal Q State / ^yl County | _ | LocoilP' ^k X3 Z DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: t) •j? in C OAHP, WASO c/> rj V?\ m STREET AND NUMBER: 'l - i H~*~! ^|T"-, r £;. -

Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the many citizens, staff, and community groups who provided extensive input for the development of this Parks, Trails, and Open Space Plan. The project was a true community effort, anticipating that this plan will meet the needs and desires of all residents of our growing County. SHASTA COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Glenn Hawes, Chair David Kehoe Les Baugh Leonard Moty Linda Hartman PROJECT ADVISORY COMMITTEE Terry Hanson, City of Redding Jim Milestone, National Park Service Heidi Horvitz, California State Parks Kim Niemer, City of Redding Chantz Joyce, Stewardship Council Minnie Sagar, Shasta County Public Health Bill Kuntz, Bureau of Land Management Brian Sindt, McConnell Foundation Jessica Lugo, City of Shasta Lake John Stokes, City of Anderson Cindy Luzietti, U.S. Forest Service SHASTA COUNTY STAFF Larry Lees, County Administrator Russ Mull, Department of Resource Management Director Richard Simon, Department of Resource Management Assistant Director Shiloe Braxton, Community Education Specialist CONSULTANT TEAM MIG, Inc. 815 SW 2nd Avenue, Suite 200 Portland, Oregon 97204 503.297.1005 www.migcom.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Plan Purpose 1 Benefits of Parks and Recreation 2 Plan Process 4 Public Involvement 5 Plan Organization 6 2. Existing Conditions ................................................................................ 7 Planning Area 7 Community Profile 8 Existing Resources 14 3. -

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest Welcome The following list of recreation activities are avail- able in the Hat Creek Recreation Area. For more detailed information please stop by the Old Station Visitor Information Center, open April - December, or our District Office located in Fall River Mills. Give Hat Creek Rim Overlook - Nearly 1 million years us a call year-around Mon.- Fri. at (530) 336-5521. ago, active faulting gradually dropped a block of Enjoy your visit to this very interesting country. the Earth’s crust (now Hat Creek Valley) 1,000 feet below the top of the Hat Creek Rim, leaving behind Subway Cave - See an underground cave formed this large fault scarp. This fault system is still “alive by flowing lava. Located just off Highway 89, 1/4 and cracking”. mile north of Old Station junction with Highway 44. The lava tube tour is self guided and the walk is A heritage of the Hat Creek area’s past, it offers mag- 1/3 mile long. Bring a lantern or strong flashlight nificent views of Hat Creek Valley, Lassen Peak, as the cave is not lighted. Sturdy Shoes and a light Burney Mountain, and, further away, Mt. Shasta. jacket are advisable. Subway Cave is closed during the winter months. Fault Hat Creek Rim Fault Scarp Vertical movement Hat Creek V Cross Section of a Lava Tube along this fault system alley dropped this block of earth into its present position Spattercone Trail - Walk a nature trail where volca- nic spattercones and other interesting geologic fea- tures may be seen. -

Geologic Gems of California's State Parks

STATE OF CALIFORNIA – EDMUND G. BROWN JR., GOVERNOR NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY – JOHN LAIRD, SECRETARY CALIFORNIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION – LISA MANGAT, DIRECTOR JOHN D. PARRISH, Ph.D., STATE GEOLOGIST DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION – DAVID BUNN, DIRECTOR PLATE 1 The rugged cliffs of Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park are composed of some of California’s Bio-regions the most tortured, twisted, and mobile rocks of the North American continent. The California’s Geomorphic Provinces rocks are mostly buried beneath soils and covered by vigorous redwood forests, which thrive in a climate famous for summer fog and powerful winter storms. The rocks only reveal themselves in steep stream banks, along road and trail cut banks, along the precipitous coastal cliffs and offshore in the form of towering rock monuments or sea stacks. (Photograph by CalTrans staff.) Few of California’s State parks display impressive monoliths adorned like a Patrick’s Point State Park displays a snapshot of geologic processes that have castle with towering spires and few permit rock climbing. Castle Crags State shaped the face of western North America, and that continue today. The rocks Park is an exception. The scenic beauty is best enjoyed from a distant exposed in the seacliffs and offshore represent dynamic interplay between the vantage point where one can see the range of surrounding landforms. The The Klamath Mountains consist of several rugged ranges and deep canyons. Klamath/North Coast Bioregion San Joaquin Valley Colorado Desert subducting oceanic tectonic plate (Gorda Plate) and the continental North American monolith and its surroundings are a microcosm of the Klamath Mountains The mountains reach elevations of 6,000 to 8,000 feet. -

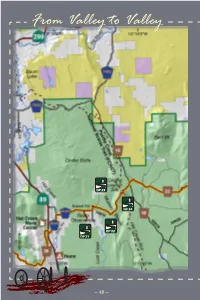

From Valley to Valley

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Cal Fire

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND FIRE PROTECTION CAL FIRE SHASTA – TRINITY UNIT FIRE PLAN Community Wildfire Protection Plan Mike Chuchel Unit Chief Scott McDonald Division Chief – Special Operations Mike Birondo Battalion Chief - Prevention Bureau Kimberly DeSena Fire Captain – Pre Fire Engineering 2008 Shasta – Trinity Unit Fire Plan 1 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................... 4 Unit Fire Plan Assessments and Data Layers................................................ 5 Fire Plan Applications...................................................................................... 6 Community Wildfire Protection Plan............................................................. 6 Unit Fire Plan Responsibilities........................................................................ 6 Key Issues .......................................................................................................... 7 2. STAKEHOLDERS................................................................................. 8 Fire Safe Organizations.................................................................................... 8 Resource Conservation Districts..................................................................... 9 Watershed Contact List ................................................................................... 9 Government Agencies..................................................................................... 13 3. UNIT OVERVIEW ............................................................................. -

PETER LASSEN NEW EVIDENCE FOUND News from the President

Volume 35, Number 2 Red Bluff, California November/December 2015 PETER LASSEN News from the President NEW EVIDENCE FOUND The Society is very excited to let you know that Please join us on Thursday, November we have been able to obtain a complete listing of 12th, at 7 pm in the West Room of the Red all interred at both Oak Hill and St. Mary's Bluff Community Center for a new cemeteries on our web page. It lists names, presentation by historian Dave Freeman on the location of grave, birth, death and interment dates works of Peter Lassen as he developed his and will be a very valuable tool for those rancho on the banks of Deer Creek near the researchers attempting to find this information, present-day town of Vina. especially if they visit the cemetery on a weekend A self-proclaimed “amateur” or after hours. Go to our home page archaeologist, Freeman has a impressive body of www.tcghsoc.org and click on "Up Dated". If you work and is a columnist for the Colusi County need a map click on "Cemeteries" then on "Red Historical Society. This spring he was invited to Bluff Oak Hill". speak about his continuing research on Lassen at When you visit our web page check out and the California-Nevada Chapter OCTA (Oregon- download the Tehama County Museum Flyer. California Trails Assoc.) symposium. This is a helpful flyer that has a list of nine Dave is known for his uniting of records museums in Tehama County, their address and research with extensive boots-on-the-ground contact information. -

Loomis Visitor Center Loomis Museum Manzanita Lake Visitor

Form 10-306 STATE: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE California COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Shasta INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Loomis Visitor Center Manzanita Lake Visitor Center Loomis Museum Manzanita Lake Museum AND/OR HISTORIC: Mae Loomis Memorial Museum STREET AND NUMBER: Building 43 CITY OR TOWN: Manzanita Lake, CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Lassen Volcanic National Park STATE: COUNTY: California 06 Shasta 089 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS CChec/c One) TO THE PUBLIC District Building |5T| Public Public Acquisition: fX] Occupied Yes: z Site Structure | | Private ||In Process | | Unoccupied |~~] Restricted o d] Object Q] Both |~~| Being Considered | | Preservation work [~] Unrestricted in progress SN.O H u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) | | Agricultural (jg Government C] Park | | Transportation | | Comments | | Commercial [""I Industrial Q Private Residence Q Other (Specify.) ^CJ3 Educational Q Military | | Religious | | Entertainment useum [ | Scientific Ul 111 Lassen Volcanic National Park, U.S. National Park Service REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: Western Region_____________ 450 Golden Gate Avenue Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE: H San Francisco California 06 > COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Shasta County Courthouse co 2 STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Redding California 06 TITLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: Federal State Catfnty •-,/ ••—— DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: er-, €£» STREET AND NUMBER: W Cl TY OR TOWN: (Check One) llent Good |~| Deteriorated [~1 Ruins [~~| Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One,) Altered [jg Unaltered Moved jg[] Original Site Exterior The Loomis Museum is a building of rustic appearance constructed of a gray, native volcanic rock with cut face random ashlar masonry. -

Apinos, Open-File Report 83-400 This Report Is Preliminary and Has Not

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The Volcano Hazards Program: Objectives and Long-Range P 1ans R. A. Bailey, P. R, Beauchemln, F, P. ~apinos, and D. W. Klick. Open-File Report 83-400 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. - - Reston 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 1 General Assessment of the Potential for Future Eruptions A. Mount St. Helens B. Other Cascade Volcanoes C, Other Western Conterminous U.S. Volcanoes D. Hawaii an Volcanoes E. Alaskan Volcanoes 111. Program bals, Objectives, and Components A. Volcanic Hazards Assessment B. Volcano Monitoring C. Fundamental Research 0. Emergency-Response Planning and Public Education IV. A Long-Range Volcano Hazards Program A. Funding his tor.^ B. General Objectives C. Specific Objectives D. Plans for Studies E. Resources F. International Cooperat ion V. The Federal Role 3 1. A. Public Need for Information about Impending 31 Volcanic Hazards B. Interstate Implications of Volcanic Disasters 32 C. Disruption of Regional and National Economies 32 0. Implication for Federal Lands 33 E. Mitigation of Subsequent Federal Disaster Assistance Costs 33 F. Need for an Integrated Research Program 33 Figure 1, Location of Potentially Hazardous Volcanoes in the U.S. 4 e Figure 2, History of Cascades Volcanism, 1800-1980 6 THE VOLCANO HAZARDS PROGRAM: OBJECTIVES AN0 LONG-RANGE PLANS I. INTRODUCTION Volcanoes and the products of volcanoes have a much greater impact on people and society than is generally perceived. Although commonly destructive, volcanic eruptions can be spectacularly beautiful and, more importantly, they have produced the very air we breathe, the water we drink, and our most fertile soils. -

Lassen Domefield Telephoto View from Parhams Point on Hat Creek Rim (Old Station Quadrangle)

May 19–20, 1915 flow upper Devastated Area Crescent Lassen dacite of Crater Peak Hill 8283 tuff cone of Raker Peak rhyodacite of Chaos Crags Krummholz Chaos Crags Mount Diller Chaos Crags dome E dome B dome F Domes of Sunflower Flat andesite of Raker Peak Hat Creek Hat Creek andesites of Badger Mountain Lassen domefield Telephoto view from Parhams Point on Hat Creek Rim (Old Station quadrangle). Remnants of the northeast lobe of the dacite flow of May 19–20, 1915 (unit d9) are exposed in the notch at the top of Lassen Peak, above the Devastated Area. The original blocky carapace of Lassen Peak (unit dl, 27±1 ka) has been removed by glaciation, whereas a blocky carapace is preserved on the unglaciated domes of Chaos Crags (units rcb, rce and rcf, 1,103±13 yr B.P.). Forested slopes in front of the domes of Chaos Crags are the rhyodacite domes of Sunflower Flat (unit rsf, 41±1 ka). Mount Diller is a remnant of the Brokeoff Volcano (590–390 ka). The slopes in front of Mount Diller, between Chaos Crags and Lassen Peak, are underlain primarily by the rhyodac- ite dome and flow of Krummholz (unit rkr, 43±2 ka, part of the Eagle Peak sequence) and the dacite of hill 8283 (unit d82, 261±5 ka, part of the Bumpass sequence) and are mantled by tephra of the Chaos Crags eruptions (unit pc, 1,103±13 yr B.P.). Crescent Crater (unit dc, 236±1 ka) is also part of the Bumpass sequence. Raker Peak is the vent for the andesite of Raker Peak (unit arp, 270±18 ka), part of the older Twin Lakes sequence. -

Lassen Volcanic National Park

LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK • CALIFORNIA • UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HAROLD L. ICKES, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ARNO B. CAMMERER, Director LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK CALIFORNIA SEASON FROM JUNE 1 TO SEPTEMBER IS UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1934 RULES AND REGULATIONS The park regulations are designed for the protection of the natural beauties as well as for the comfort and convenience of visitors. The com plete regulations may be seen at the office of the superintendent of the park. The following synopsis is for the general guidance of visitors, who are requested to assist in the administration of the park by observing CONTENTS the rules. PAGE Automobiles.—Many sharp unexpected curves exist on the Lassen Peak Loop Highway, and fast driving—over 25 miles per hour in most places—is GEOLOGIC HISTORY 2 dangerous. Drive slowly, keeping always well to the right, and enjoy the THE ANCIENT BROKEOFF CRATER 5 scenery. Specimens and souvenirs.—In order that future visitors may enjoy the SOLFATARAS 6 park unimpaired and unmolested, it is strictly prohibited to break any THE CINDER CONE 8 formation; to take any minerals, lava, pumace, sulphur, or other rock MOUNTAINS 9 specimens; to injure or molest or disturb any animal, bird, tree, flower, or shrub in the park. Driving nails in trees or cutting the bark of trees in OTHER INTERESTING FEATURES I0 camp grounds is likewise prohibited and strictly enforced. Dead wood WILD ANIMALS :: may be gathered for camp fires. Trash.—Scraps of paper, lunch refuse, orange peelings, kodak cartons, FISHING :4 chewing-gum wrappers, and similar trash scattered along the roads and CAMPING r5 trails and camp grounds and parking areas are most objectionable and unsightly. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections.