Averymosesrosencranz2009.Pdf (12.98Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV-Decuble.Pdf

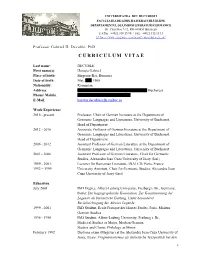

UNIVERSITATEA DIN BUCUREŞTI FACULTATEA DE LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE DEPARTAMENTUL DE LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI GERMANICE Str. Pitar Moş 7-13, RO-010451 Bucureşti Telefon: +4021.318.15.80 / Fax: +4021.312.13.13 http://www.unibuc.ro/prof/decuble_h_g/ Professor Gabriel H. Decuble, PhD CURRICULUM VITAE Last name: DECUBLE First name(s): Horaţiu Gabriel Place of birth: Sîngeorz-Băi, Romania Date of birth: Mai, 29th, 1968 Nationality: Romanian Address: Calea Moşilor 308, Nr. 48 bis, Apt. 39, 020902 Bucharest Phone/ Mobile: +40 31 106 24 25/ +40 737 214 742 E-Mail: [email protected] Work Experience 2016 - present Professor, Chair of German literature at the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Bucharest, Head of Department 2012 - 2016 Associate Professor of German literature at the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Bucharest, Head of Department 2006 - 2012 Assistant Professor of German Literature at the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Bucharest 2001 - 2006 Assistant Professor of German Literature, Chair for Germanic Studies, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Jassy (Iasi) 1999 - 2001: Lecturer for Romanian Literature, INALCO, Paris, France 1992 – 1999 University Assistant, Chair for Germanic Studies, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Jassy (Iasi) Education July 2001 PhD Degree, Albert-Ludwig University, Freiburg i. Br., Germany; thesis: Die hagiographische Konvention. Zur Konstituierung der Legende als literarische Gattung. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung -

Caiete ISSN 1220*6350 FNSA

4(318)7 2014 caiete ISSN 1220*6350 FNSA Revistä editatä de Fundatia Nationalä pentru Stiintä si Artä / / r r r f Director: Eugen SIMION Dimitrie Cantemir - un „ homo europaeus " diu Räsärit de Eugen Simion Etre un hon europeen de Dan Hältlicä Identitate europeanä si integrare europeanä Germanistul * v George Gutu - la aniversare de Gabriela Dantis Eveniment iaDÄDa ©ÄKpf5ft Germanistul George Gutu - la aniversare Articolul este prilejuit de aniversarea a 70 de ani de viatä ai germanistului George Gutu, profesor la Universitatea din Bucure§ti, personalitate marcantä a germanisticii din Romänia, excelent orga- nizator indeosebi in perioada de dupä 1990, atät prin activitatea didacticä, cät §i prin initiativa revigorärii disciplinei la nivel national (fondarea „Societätii Germani§tilor din Romänia, infiintarea unor publicatii de profil, precum „Zeitschrift der Germanisten Rumäniens", „«tran- scarpathica». germanistisches jahrbuch rumänien", bilingvul „Rumänisches Goethe- Jahrbuch! Anuarul romänesc Goethe", infiintarea Centrului de Cercetare §i Excelentä „Paul Celan" al Universitätii din Bucure§ti, initierea reluärii traditiei congreselor de germanisticä din tarä, cu participare internationalä, §i prin coordonarea seriei editoriale de studii „GGR - Beiträge zur Germanistik"). Succintul bilant este intregit de activitatea sa exegeticä, dedicatä cu precädere literaturii de expresie germanä din Romänia, precum §i lui Paul Celan. De asemenea, de activitatea editorialä (de mentionat §i noua serie a operei goetheene) §i de traducere in romäne§te a unor impor- tante texte din literaturile germane. Toate acestea ilustreazä vocatia sa constructivä, de mediator nitre cele douä culturi. Cuvinte-cheie: germanistul George Gutu, germanistica romäneascä actualä, literatura de expresie germanä din Romänia, studii despre Paul Celan, traduceri din germanä in romäne§te. -

CV Ion Lihaciu

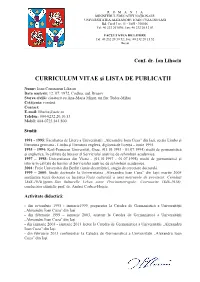

R O M A N I A MINISTERUL EDUCATIEI NAŢIONALE UNIVERSITATEA ALEXANDRU IOAN CUZA DIN IASI Bd. Carol I nr. 11 - IASI - 700506 Tel: 40 232 201010; Fax: 40 232 20 12 01 FACULTATEA DE LITERE Tel: 40 232 20 10 52; Fax: 40 232 20 11 52 Decan Conf. dr. Ion Lihaciu CURRICULUM VITAE şi LISTA DE PUBLICAŢII Nume: Ioan-Constantin Lihaciu Data naşterii: 12. 07. 1972, Codlea, jud. Braşov Starea civilă: căsătorit cu Ana-Maria Minuţ, un fiu: Tudor-Mihai Cetăţenia: română Contact: E-mail: [email protected] Telefon: 004-0232.20.10.53 Mobil: 004-0723.841.800 Studii: 1991 - 1995: Facultatea de Litere a Universităţii „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi, secţia Limba şi literatura germană - Limba şi literatura engleză, diplomă de licenţă – iunie 1995. 1993 – 1994: Karl-Franzens Universität, Graz, (01.10.1993 - 01.07.1994) studii de germanistică şi anglistică, în calitate de bursier al Serviciului austriac de schimburi academice. 1997 – 1998: Universitatea din Viena - (01.10.1997 - 01.07.1998) studii de germanistică şi istorie în calitate de bursier al Serviciului austriac de schimburi academice. 2004: Freie Universität din Berlin (iunie-decembrie), stagiu de cercetare doctorală. 1999 – 2005: Studii doctorale la Universitatea „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi; martie 2005 susţinerea tezei doctorat cu lucrarea Viaţa culturală a unei metropole de provincie: Cernăuţi 1848-1918 (germ. Das kulturelle Leben einer Provinzmetropole: Czernowitz 1848-1918); conducător ştiinţific prof. dr. Andrei Corbea-Hoişie. Activitate didactică: - din octombrie 1995 - ianuarie1999, preparator la Catedra de Germanistică a Universităţii „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi - din februarie 1999 – ianuarie 2003, asistent la Catedra de Germanistică a Universităţii „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi - din ianuarie 2003 - ianuarie 2013 lector la Catedra de Germanistică a Universităţii „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi. -

Cheie Laura Naţionalitate Data Naşterii

Curriculum vitae Europass Informaţii personale Nume / Prenume Cheie Laura Naţionalitate Data naşterii Ocupația și locul de muncă Conf. univ. dr. actual Facultatea de Litere, Istorie și Teologie, Departamentul de limbi și literaturi moderne, Colectivul de limba și literatura germană, Universitatea de Vest din Timișoara Experienţa profesională Perioada Octombrie 1999 – iunie 2015 Funcţia sau postul ocupat Lector universitar doctor în Colectivul de limba şi literatura germană al Departamentului de limbi și literaturi moderne din Facultatea de Litere, Istorie și Teologie a Universităţii de Vest din Timişoara Activităţi şi responsabilităţi Discipline predate: Literatură germană, Cultură și civilizație germană, Retorică principale generală și aplicată, Analiza discursului literar, media și politic, Teoria comunicării și comunicare interculturală, Inter- și multiculturalitate în Bucovina, Teoria și practica traducerii literare. Activitate de cercetare: publicare de cărți, studii și articole în reviste științifice și culturale (cf. lista cu publicații), participare la congrese, conferințe și colocvii, redactor al revistei de specialitate „Temeswarer Beiträge zur Germanistik” (TBG) și al revistei „Analele Universității de Vest din Timișoara. Seria Științe Filologice” (AUT). Activitate administrativă în cadrul colectivului de germană și al Departamentului de limbi și literaturi moderne: organizare de sesiuni științifice, conducere de lucrări de licență și masterat. Numele şi adresa angajatorului Facultatea de Litere, Istorie și Teologie, Departamentul -

%Beitraege Ultima Corectura.Pmd

Ein Beitrag zur Wort- und Namengeschichte 175 Bücher und Publikationen in deutscher Sprache Aus der rumänischen Verlagsproduktion 1989-1999 Horst Schuller Die folgende Übersicht versucht an der Bruchstelle der politischen Wende in Rumänien anzusetzen und die Produktion von Büchern in deutscher Sprache (und einigen in rumänischer Sprache zur deutschen Literatur und Sprache) im Jahrzehnt von 1989 bis 1999 zu erfassen. Damit möchten wir einen Teil der neuen Unübersichtlichkeit abbauen, die sich durch Veränderungen im Verlagswesen, im Buchvertrieb und in der bibliographischen Evidenz von Neuerscheinungen ergeben hat. Aufgenommen wurden auch Deutsch-Lehrbücher und Wörterbücher mit mehreren Auflagen, um die Dichte und zeitliche Streuung der jeweiligen Produktion zu zeigen. Nicht verzeichnet wurden periodisch unregelmäßig herausgebrachte Schülerzeitschriften oder Informationsblätter von Forumsorganisationen und Kirchengemeinden. Durch die Privatisierung von Vorwende-Verlagen, aber vor allem durch die Gründung neuer Unternehmen kann nicht mehr, oder nur in sehr begrenzten Fällen von einer Kontinuität der Verlagsnamen und Profile gesprochen werden. Wenn vor der Wende vor allem in den Verlagen Kriterion, Dacia, Ion Creangã, Albatros, Facla, Meridiane oder im Lehrbuchverlag und im Politischen Verlag Bücher in deutscher Sprache verlegt wurden, verlagerte sich nach 1990 das Schwergewicht aus der Hauptstadt in die Region, von wenigen Verlagshäusern zu einer Fülle von Institutionen, die nun Publikationen und Bücher in deutscher Sprache von Autoren schöngeistiger, -

The Vilenica Almanac 2011

vilkenica-zbornik_za_tisk-TISK4.pdf 1 30.8.2011 21:36:02 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K vilkenica-zbornik_za_tisk-TISK4.pdf 1 30.8.2011 21:36:02 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 26. Mednarodni literarni festival Vilenica / 26th Vilenica International Literary Festival Vilenica 2011 © Nosilci avtorskih pravic so avtorji sami, če ni navedeno drugače. © The authors are the copyright holders of the text unless otherwise stated. Uredila / Edited by Tanja Petrič, Gašper Troha Založilo in izdalo Društvo slovenskih pisateljev, Tomšičeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana Zanj Milan Jesih, predsednik Issued and published by the Slovene Writers’ Association, Tomšičeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana Milan Jesih, President Jezikovni pregled / Language editor Jožica Narat, Alan McConnell-Duff Grafično oblikovanje / Design Goran Ivašić Prelom / Layout Klemen Ulčakar Tehnična ureditev in tisk / Technical editing and print Ulčakar&JK Naklada / Print run 700 izvodov / 700 copies Ljubljana, avgust 2011 / August 2011 Zbornik je izšel s finančno podporo Javne agencije za knjigo RS in Ministrstva za kulturo RS. The almanac was published with financial support of the Slovenian Book Agency and Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 821(4)-82 7.079:82(497.4Vilenica)”2011” MEDNARODNI literarni festival (26 ; 2011 ; Vilenica) Vilenica / 26. Mednarodni literarni festival = International Literary Festival ; [uredila Tanja Petrič, Gašper Troha]. - Ljubljana : Društvo slovenskih pisateljev = Slovene Writers’ Association, 2011 ISBN 978-961-6547-59-8 1. Petrič, Tanja, 1981- 257388544 Kazalo / Contents Nagrajenec Vilenice 2011 / Vilenica 2011 Prize Winner Mircea Cărtărescu . 6 Literarna branja Vilenice 2011 / Vilenica 2011 Literary Readings Pavel Brycz . -

Sorin Gadeanu

CURRICULUM VITAE Informa ţii personale Nume / Prenume SORIN GADEANU Adresa Str. Vasile Goldi ş 2 / C / 12 (fost ă Buftea) RO - 1900 TIMI ŞOARA Telefon Tel.: +40-256-490-276 Mobil: 0729-195545 E-mail [email protected] Cetăţenia român ă Data naşterii 03. 10. 1965 Sex MASCULIN Experien ţa profesional ă Perioada 22 .02. 2016 - prezent Funcţia sau postul ocupat PROFESOR UNIVERSITAR TITULAR Numire: Decizia Rectorului Nr. 1426 / 15. 02. 2016, cf. validare Senat din 11. 02. 2016 Numele ş i adresa angajatorului Departamentul de Limbi Str ăine şi Comunicare UNIVERSITATEA TEHNICĂ DE CONSTRUCŢII BUCUREŞTI Tipul activităţii sau sectorul de activitate înv ăţă mânt superior Perioada 01. 01. 2011 – 21. 02. 2016: Funcţia sau postul ocupat PROFESOR UNIVERSITAR TITULAR Numire: Ordin Ministru 5896 / 20. 12. 2010, Anexa Nr. 14 Numele şi adresa angajatorului Facultatea de Limbi şi Literaturi Str ăine UNIVERSITATEA SPIRU HARET Bucureşti, Str. Ion Ghica 13 Tipul activităţii sau sectorul de activ itate înv ăţă mânt superior Perioada 21. 02. 2000 – 31. 12. 2010 Funcţia sau postul ocupat CONFEREN ŢIAR UNIVERSITAR TITULAR Numire: Ordin Ministru 3336 / 8. 03. 2000, Anexa Nr. 1 Numele şi adresa angajatorului Facultatea de Limbi şi Literaturi Str ăine UNIVERSITATEA SPIRU HARET Bucureşti, Str. Ion Ghica 13 Tipul activităţii sau sectorul de activitate înv ăţă mânt superior Pag 1 / 44 - Curriculum vitae SORIN GADEANU Perioada 01. 10. 1999 – 20. 02. 2000 Funcţia sau post ul ocupat Suplinirea unui post de SUPLINIREA UNUI POST DE CONFEREN ŢIAR UNIVERSITAR Numele şi adresa angajatorului Facultatea de Limbi şi Literaturi Str ăine UNIVERSITATEA SPIRU HARET Bucure şti, Str. -

Ioan–Constantin Lihaciu Data Naşterii: 12

CURRICULUM VITAE şi LISTA DE PUBLICAŢII Nume: Ioan–Constantin Lihaciu Data naşterii: 12. 07. 1972, Codlea, jud. Braşov Starea civilă: căsătorit cu Ana–Maria Minuţ, un fiu: Tudor–Mihai Cetăţenia: română Contact: E–mail: [email protected] Mobil: 004–0723.841.800 Cuprins: I. Studii II. Activitate didactică; III. Activitate administrativă; IV. Burse de studiu şi stagii de cercetare şi predare în străinătate: – 18 V. Membru în proiecte: – 14 VI. Membru în colectivul unor centre de cercetare: – 3 VII. Participări la congrese, simpozioane şi conferinţe: – 56 a) organizate în străinătate: – 32 b) organizate în ţară: – 24 VIII. Volume: (autor, coautor, coeditor) – 11 IX. Studii, articole şi recenzii publicate în reviste de specialitate şi volume colective: – 61 a) publicate în străinătate: – 33 b) publicate în ţară: – 28 I. – Studii: 1991 – 1995: Facultatea de Litere a Universităţii „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi, secţia Limba şi literatura germană – Limba şi literatura engleză, diplomă de licenţă – iunie 1995. 1993 – 1994: Karl–Franzens Universität, Graz, (01.10.1993 – 01.07.1994) studii de germanistică şi anglistică, în calitate de bursier al Serviciului austriac de schimburi academice. 1997 – 1998: Universitatea din Viena – (01.10.1997 – 01.07.1998) studii de germanistică şi istorie în calitate de bursier al Serviciului austriac de schimburi academice. 1999 – 2000: Universitatea din Viena – (01.03.1999 – 01.03.2000) studii de germanistică în calitate de bursier al Serviciului austriac de schimburi academice. 2004: Freie Universität din Berlin (iunie–decembrie), stagiu de studiu şi cercetare doctorală. 1999 – 2005: Studii doctorale la Universitatea „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iaşi; martie 2005 susţinerea tezei doctorat cu lucrarea Viaţa culturală a unei metropole de provincie: Cernăuţi 1848–1918 (germ. -

Zbornik Vilenica 2017

32. Mednarodni literarni festival 32nd International Literary Festival LITERATURA, KI SPREMINJA SVET, KI SPREMINJA LITERATURO LITERATURE THAT CHANGES THE WORLD THAT CHANGES LITERATURE Vilenica 2017 32. Mednarodni literarni festival Vilenica / 32nd Vilenica International Literary Festival Vilenica 2017 © Nosilci avtorskih pravic so avtorji sami, če ni navedeno drugače. © The authors are the copyright holders of the text unless otherwise stated. Uredili / Edited by Kristina Sluga, Maja Kavzar Hudej Založilo in izdalo Društvo slovenskih pisateljev, Tomšičeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana Zanj Ivo Svetina, predsednik Issued and published by the Slovene Writers’ Association, Tomšičeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana Ivo Svetina, President Jezikovni pregled / Proofreading Jožica Narat, Jason Blake Življenjepisi v slovenščini / English Translation Kristina Sluga, Petra Meterc Grafično oblikovanje naslovnice / Cover design Barbara Bogataj Kokalj Prelom / Layout Klemen Ulčakar Tehnična ureditev in tisk / Technical editing and print Ulčakar grafika Naklada / Print run 300 izvodov / 300 copies Ljubljana, avgust 2017 / August 2017 Zbornik je izšel s finančno podporo Javne agencije za knjigo Republike Slovenije. The almanac was published with the financial support of the Slovenian Book Agency. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 7.079:82(497.4Vilenica)”2017”(082) MEDNARODNI literarni festival (32 ; 2017 ; Vilenica) Vilenica : literatura, ki spreminja svet, ki spreminja literaturo = literature that changes the world that changes -

Teaching the Holocaust

w W»W f)^ Volume LII No. 1 January 1997 £3 (to non-members) Unhealthy An ongoing debate among Jewish, and other, pedagogues appetite ifty years after the Fuehrer's Teaching the Holocaust Fdeath the German public's appetite for hough the Holocaust now figures as a topic in 1914 was such a calamity that it could be de Hitleriana remains the National Curriculum, and the Imperial scribed as the collective mental breakdown of dismayingly keen. War Museum will soon have a permanent humanity. In its wake came horrors - especially in Right now whole T exhibit, disagreements about the value of 'teaching Russia and Germany - which only ended with the forests are being cut the Holocaust' remain. deaths of Hitler and Stalin. Since then there has down for the been, at least in the West, resumption of moral-cum- Austrian historian Critics divide into two groups: those who oppose material progress - hand in hand with ever wider Brigitte Hamann's such teaching on pragmatic grounds, and 'philo tome entitled sophical' opponents. availability of education. Of course, the picture is far Hitler's Vienna The 'pragmatists' point to the psychological bur from uniformly white, but on looking into the pock (Piper Verlag). den acquaintance with the facts of genocide might ets of darkness one finds that the likes of Le Pen, The book acquaints impose on growing children (not least Jewish ones). Haider or Zhirinovsky are borne along the resent readers with a The 'philosophers', on the other hand, reject the ment of the under-educated. It is in the selfsame philosemitic young assumption that education can inculcate morality as 'constituency of the ignorant' that Holocaust de Adolf, who only fanciful pie-in-the-sky, and quote the number of nial flourishes. -

Buch Mitteilungen 2017.Indb

„Gerne denke ich an Euch im winterlichen Tirol der starken Farben …“ Stella Rotenbergs Beziehung zu Tirol: Der Briefwechsel mit Hermann Kuprian und die Kontakte in Innsbruck1 von Chiara Conterno (Bologna) Einführung Stella Rotenberg (geb. Siegmann) wurde am 27. März 1915 in Wien in eine jüdische assimilierte Familie hineingeboren. Ihr Bruder, Erwin, kam 1914 auf die Welt. Sie verbrachten ihre Kindheit und Jugend in der Hannoverstraße 17 in der Brigittenau, dem 20. Wiener Gemeindebezirk. Der Vater, Bernhard Siegmann, war Textilhänd ler. Stella und Erwin Siegmann wuchsen in bescheidenen, jedoch für Bildung offenen Verhältnissen auf, denn die Familie war aufgeschlossen und ließ den Kindern einen großen Spielraum. Schon in der Schule wurde die Dichterin mit antisemitischen Äußerungen konfrontiert.2 Nach der Volksschule besuchte sie das Realg ym nasium; mit 15 nahm sie an einer Schüler kolonie teil und lernte in dieser Zeit Jura Soyfer kennen. Die Jahre 1926–1930 sollten die friedlichsten in ihrer Jugend gewesen sein, obwohl sie die Ereignisse des Jahres 1927 – insbesondere den Brand des Justizpalastes am 15. Juli 1927 – miterleben musste. Auch die österreichischen Februarkämpfe im Jahr 1934 prägten sich in ihrer Erinnerung ein.3 Nach der Matura, im Sommer 1934, unter- nahm sie mit ihrem Bruder und einem Freund eine Tour durch Europa, wobei sie Italien, Frankreich, Belgien und Holland bereiste. Während dieser Reise wurde Stella Siegmann des sich verbreiten- den Antisemitismus stärker bewusst, da sie in Mailand Flüchtlinge aus Deutschland traf. Zurück in Wien begann sie im Herbst 1934 das Studium der Medizin, was für jüdische Frauen jener Zeit keine Selbstverständlichkeit war. Der Anschluss, am 12. -

WP992.Pdf (36.46Kb Application/Pdf)

The “Lesser Traumatized”: Exile Narratives of Austrian Jews Adi Wimmer Department of English University of Klagenfurt November 1999 Working Paper 99-2 ©1999 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce CAS Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624- 9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] Throughout 1988—Austria’s “Year of Recollection,” or Gedenkjahr as it was called—many historians, politicians, organizations, and media took a hard look at Austria’s merger with Hitler’s Germany in March of 1938. So did university professors, and with good reason. Prior to 1938, Austrian universities had been hotbeds of German nationalism. There were numerous vicious attacks against Jewish students, but the professors looked the other way. By their silence, they encouraged the attacks. As 1988 approached, there was a consensus amongst Austrian professors, particularly by those working in the humanities, that we must never again fail to speak out against the dangers of intolerance or racism.