Visually Engaging and Student-Friendly World History Survey CRAIG 4Tlc Sc 8/7/08 2:24 PM Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beta Samati: Discovery and Excavation of an Aksumite Town Michael J

Beta Samati: discovery and excavation of an Aksumite town Michael J. Harrower1,*, Ioana A. Dumitru1, Cinzia Perlingieri2, Smiti Nathan3,Kifle Zerue4, Jessica L. Lamont5, Alessandro Bausi6, Jennifer L. Swerida7, Jacob L. Bongers8, Helina S. Woldekiros9, Laurel A. Poolman1, Christie M. Pohl10, Steven A. Brandt11 & Elizabeth A. Peterson12 The Empire of Aksum was one of Africa’smost influential ancient civilisations. Traditionally, most archaeological fieldwork has focused on the capital city of Aksum, but recent research at the site of Beta Samati has investigated a contempor- aneous trade and religious centre located between AksumandtheRedSea.Theauthorsoutlinethe discovery of the site and present important finds from the initial excavations, including an early basilica, inscriptions and a gold intaglio ring. From daily life and ritual praxis to international trade, this work illuminates the role of Beta Samati as an administrative centre and its signifi- cance within the wider Aksumite world. Keywords: Africa, Ethiopia, Aksum, ancient trade, ancient states 1 Department of Near Eastern Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Gilman 113, 3400 North Charles Street, Balti- more, MD 21218, USA 2 Center for Digital Archaeology, 555 Northgate #270, San Rafael, CA 94903, USA 3 Life Design Lab, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 4 Archaeology and Heritage Management, P.O. Box 1010, Aksum University, Aksum, Ethiopia 5 Department of Classics, Yale University, 344 College Street, P.O. Box 208266, New Haven, CT 06520, -

Stevenson Memorial Tournament 2018 Edited by Jordan

Stevenson Memorial Tournament 2018 Edited by Jordan Brownstein, Ewan MacAulay, Kai Smith, and Anderson Wang Written by Olivia Lamberti, Young Fenimore Lee, Govind Prabhakar, JinAh Kim, Deepak Moparthi, Arjun Nageswaran, Ashwin Ramaswami, Charles Hang, Jacob O’Rourke, Ali Saeed, Melanie Wang, and Shamsheer Rana With many thanks to Brad Fischer, Ophir Lifshitz, Eric Mukherjee, and various playtesters Packet 2 Tossups: 1. An algorithm devised by this person uses Need, Allocated, and Available arrays to keep the system in a safe state when allocating resources. This scientist, Hoare, and Dahl authored the book Structured Programming, which promotes a paradigm that this man also discussed in a handwritten manuscript that popularized the phrase “considered harmful.” Like Prim’s algorithm, an algorithm by this person can achieve the optimal runtime of big-O of E plus V-log-V using a (*) Fibonacci heap. This man expanded on Dekker’s algorithm to propose a solution to the mutual exclusion problem using semaphores. The A-star algorithm uses heuristics to improve on an algorithm named for this person, which can fail with negative-weight edges. For 10 points, what computer scientist’s namesake algorithm is used to find the shortest path in a graph? ANSWER: Edsger Wybe Dijkstra [“DIKE-struh”] <DM Computer Science> 2. A design from this city consists of a window with a main panel and two narrow double-hung windows on both sides. The DeWitt-Chestnut Building in this city introduced the framed tube structure created by an architect best known for working in this city. Though not in Connecticut, a pair of apartment buildings in this city have façades with grids of steel and glass curtain walls and are called the “Glass House” buildings. -

Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa This simulation, while focused around the Ethiopia-Eritrea border conflict, is not an attempt to resolve that conflict: the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) already has a peace plan on the table to which the two parties in conflict have essentially agreed. Rather, participants are asked, in their roles as representatives of OAU member states, to devise a blueprint for preventing the Ethiopian-Eritrean conflict from spreading into neighboring countries and consuming the region in even greater violence. The conflict, a great concern particularly for Somalia and Sudan where civil wars have raged for years, has thrown regional alliances into confusion and is increasingly putting pressure on humanitarian NGOs and other regional parties to contain the conflict. The wars in the Horn of Africa have caused untold death and misery over the past few decades. Simulation participants are asked as well to deal with the many refugees and internally displaced persons in the Horn of Africa, a humanitarian crisis that strains the economies – and the political relations - of the countries in the region. In their roles as OAU representatives, participants in this intricate simulation witness first-hand the tremendous challenge of trying to obtain consensus among multiple actors with often competing agendas on the tools of conflict prevention. Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn -

Digest #: Title

#9052 TTHHEE LLIIVVIINNGG SSAANNDDSS AMBROSE VIDEO PUBLISHING 2000 Grade Levels: 9-13+ 52 minutes DESCRIPTION Focuses on animal life in four extremely inhospitable deserts: the Namib's adaptive elephant, a dromedary roundup in Australia's outback, fish in thermal lakes in Mexico's Chihuahua desert, and the Sahara's Ennedi crocodiles. Survival is an eternal challenge to any life in these places. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: Science: Life Sciences • Standard: Understands relationships among organisms and their physical environment Benchmark: Knows how the interrelationships and interdependencies among organisms generate stable ecosystems that fluctuate around a state of rough equilibrium for hundreds or thousands of years (e.g., growth of a population is held in check by environmental factors such as depletion of food or nesting sites, increased loss due to larger numbers of predators or parasites) • Standard: Understands biological evolution and the diversity of life Benchmark: Understands the concept of natural selection (e.g., when an environment changes, some inherited characteristics become more or less advantageous or neutral, and chance alone can result in characteristics having no survival or reproductive value; this process results in organisms that are well suited for survival in particular environments) INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. To list physical features and capabilities of the desert elephant, gemsbok, warthog, ostrich, dromedary, pupfish, and crocodile. 2. To research how these animals survive in their environment. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Evolutionary Adaptations Desert Elephant of the Namib Desert (Namibia): • “Snowshoe feet” provide a soft wide track on sand. • It survives days without water while the elephants of the savanna of East Africa drink 40 to 50 gallons a day. -

Identity in Ethiopia: the Oromo from the 16Th to the 19Th Century

IDENTITY IN ETHIOPIA: THE OROMO FROM THE 16 TH TO THE 19 TH CENTURY By Cherri Reni Wemlinger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Washington State University Department of History August 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of Cherri Reni Wemlinger find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Chair ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT It is a pleasure to thank the many people who made this thesis possible. I would like to acknowledge the patience and perseverance of Heather Streets and her commitment to excellence. As my thesis chair she provided guidance and encouragement, while giving critical advice. My gratitude for her assistance goes beyond words. Thanks are also due to Candice Goucher, who provided expertise in her knowledge of Africa and kind encouragement. She was able to guide my thoughts in new directions and to make herself available during the crunch time. I would like to thank David Pietz who also served on my committee and who gave of his time to provide critical input. There are several additional people without whose assistance this work would have been greatly lacking. Thanks are due to Robert Staab, for his encouragement, guidance during the entire process, and his willingness to read the final product. Thank you to Lydia Gerber, who took hours of her time to give me ideas for sources and fresh ways to look at my subject. Her input was invaluable to me. -

PERSIANS, PORTS, and PEPPER the Red Sea Trade in Late Antiquity

!"#$%&'$()!*#+$()&',)!"!!"# +-.)#./)$.0)+10/.)23)405.)&35267258 91803)40//: &)5-.:2:):7;<255./)5= )5-.)>0?7@58)=A)B10/705.)03/)!=:5/=?5=10@)$57/2.: )23)C01520@)A7@A2@@<.35)=A)5-.)1.6721.<.35:)A=1)5-. )D&)/.E1..)23)F@0::2?0@)$57/2.: ,.C015<.35)=A)F@0::2?:)03/)#.@2E2=7:)$57/2.: >0?7@58)=A)&15: G32H.1:258)=A)*550I0 J)91803)40//:()*550I0()F030/0()KLMN &;:510?5 !"#$#%"&'%(##)%&)%*)+$#&'#,%*)-#$#'-%*)%./0#1'%+/))#+-*/)'%2*-"%-"#%3&$%4&'-%/5#$%-"#%+/6$'#%/7% -"#%8&'-%9:%;#&$'<%!"*'%"&'%$#'68-#,%*)%-"#%=6(8*+&-*/)%/7%0&);%&$-*+8#'%&),%0/)/>$&="'%&(/6-%-"#% ./0&)%*)5/85#0#)-%*)%-"#%.#,%?#&%2"*+"%2&'%-"#%@#;%0&$*-*0#%$#>*/)%8*)@*)>%-"#%3&$%4&'-%2*-"%-"#% A#'-<%!"*'%-"#'*'%';)-"#'*B#'%-"#%$#+#)-%'+"/8&$'"*=%/)%-"#%.#,%?#&%-$&,#%*)%C&-#%D)-*E6*-;%(;%0#$>*)>% &88%/7%-"#%0/'-%6=%-/%,&-#%*)7/$0&-*/)%*)-/%&%+/)+*'#%)&$$&-*5#<%F)%/$,#$%-/%&++/0=8*'"%-"*'G%-"$##%0&H/$% '/6$+#'%/7%*)7/$0&-*/)%"&5#%(##)%&)&8;B#,<%3*$'-8;G%-"#%"*'-/$*+&8%-*0#%7$&0#%/7%&88%/7%-"#%0&H/$%$#>*/)'% /7%-"#%.#,%?#&%*)+86,*)>%4>;=-G%D@'60G%&),%I*0;&$%"&5#%(##)%8&*,%/6-%*)%&%'-$&*>"-%7/$2&$,%)&$$&-*5#<% !"*'%/77#$'%-"#%0/'-%=#$-*)#)-%(&+@>$/6),%*)7/$0&-*/)%7/$%-"#%,#5#8/=0#)-%/7%.#,%?#&%-$&,#<%?#+/),8;G% -"#%0/'-%6=%-/%,&-#%&$+"&#/8/>*+&8%#5*,#)+#%"&'%(##)%*)+/$=/$&-#,%*)-/%&%,#'+$*=-*/)%/7%-"#%&)+*#)-% 0&$*-*0#%-$&,#%*)7$&'-$6+-6$#%/7%-"#%.#,%?#&%&),%F),*&)%J+#&)<%!"#%&$+"&#/8/>*+&8%#5*,#)+#%($/&,#)'% /6$%@)/28#,>#%/7%-"#%$/&,'%-"$/6>"%-"#%4&'-#$)%K#'#$-%/7%4>;=-G%-"#%=/$-'%/7%-"#%.#,%?#&G%&),%-"#% ,#5#8/=0#)- % /7 % -"# % F),*&) % '6(+/)-*)#)- % 0/$# % >#)#$&88;<%!"*$,8;G% -"*' % -

Thekingdomofaksum Andeastafricantrade

199-202-0208s2 10/11/02 3:45 PM Page 199 TERMS & NAMES 2 • Aksum The Kingdom of Aksum • Adulis • Ezana and East African Trade MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW The kingdom of Aksum became an Ancient Aksum, which is now Ethiopia, international trading power and is still a center of Eastern Christianity. adopted Christianity. SETTING THE STAGE In the eighth century B.C., before the Nok were spreading their culture throughout West Africa, the kingdom of Kush in East Africa had become powerful enough to conquer Egypt. (See Chapter 4.) However, fierce Assyrians swept into Egypt during the next century and drove the Kushite pharaohs south. Kush nev- ertheless remained a powerful kingdom for over 1,000 years—until it was conquered by another even more powerful kingdom. The Rise of the Kingdom of Aksum The kingdom that arose was Aksum (AHK•soom). It was located south of Kush on a rugged plateau on the Red Sea, in what is now Eritrea and Ethiopia. A legend traces the founding of the kingdom of Aksum and the Ethiopian royal dynasty to the son of King Solomon of ancient Israel and the Queen of Sheba. That dynasty includes the 20th-century ruler Haile Selassie. In fact, the history of Aksum may have begun as early as 1000 b.c., when Arab peoples crossed the Red Sea into Africa. There they mingled with Kushite herders and farmers and passed along their written language, Ge’ez (GEE•ehz). They also Mediterranean Aksum, A.D. 300–700 shared their skills of working stone and Sea building dams and aqueducts. -

The Aksumites in South Arabia: an African Diaspora of Late Antiquity

Chapter 11 The Aksumites in South Arabia: An African Diaspora of Late Antiquity George Hatke 1 Introduction Much has been written over the years about foreign, specifically western, colo- nialism in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as about the foreign peoples, western and non-western alike, who have settled in sub-Saharan Africa during the modern period. However, although many large-scale states rose and fell in sub- Saharan Africa throughout pre-colonial times, the history of African imperial expansion into non-African lands is to a large degree the history of Egyptian invasions of Syria-Palestine during Pharaonic and Ptolemaic times, Carthagin- ian (effectively Phoenician) expansion into Sicily and Spain in the second half of the first millennium b.c.e, and the Almoravid and Almohad invasions of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. However, none of this history involved sub-Saharan Africans to any appreciable degree. Yet during Late Antiquity,1 Aksum, a sub-Saharan African kingdom based in the northern Ethi- opian highlands, invaded its neighbors across the Red Sea on several occasions. Aksum, named after its capital city, was during this time an active participant in the long-distance sea trade linking the Mediterranean with India via the Red Sea. It was a literate kingdom with a tradition of monumental art and ar- chitecture and already a long history of contact with South Arabia. The history of Aksumite expansion into, and settlement in, South Arabia can be divided into two main periods. The first lasts from the late 2nd to the late 3rd century 1 Although there is disagreement among scholars as to the chronological limits of “Late Antiq- uity”—itself a modern concept—the term is, for the purposes of the present study, used to refer to the period from ca. -

AKSUM Ancient East African Empire

7 AKSUM Ancient East African Empire 950L BY DAVID BAKER, ADAPTED BY NEWSELA The Aksum Empire was the result of two world hubs sharing their collective learning about agriculture. It rose to become a great power in the ancient world. The key to its rise was the crucial link it formed between East and West on the supercontinent of Afro-Eurasia. EAST AFRICA Copper and bronze were rare in the region, so they did not go through a bronze age. Instead, they transitioned directly to iron. Some people in the region still foraged with- East Africa was the cradle of our species. For millions of years, many of our hominine out domesticating anything. However, the knowledge transmitted from Southwest Asia ancestors roamed across the land. It is ultimately the homeland of every human being and Egypt created a mixture of the two lifeways of foraging and agriculture. To the spread across the planet. Additionally, East Africa was the region that birthed one of south, the rest of Africa would transition to agriculture much more slowly. But East the mightiest of African civilizations: the Aksum Empire. At its height in the third cen- Africa was jolted by two major hubs into the agrarian era. tury CE, some ancient writers considered it one of the four great powers of the world, alongside Rome, Persia, and China. Thanks to its position in the web of collective By 1000 BCE, hunting and gathering was on the decline. More and more people were learning in Afro-Eurasia, it rose to become one of the most complex agrarian civiliza- farming. -

A SELECTION of TEXTS by Adam Lowe & Charlotte Skene Catling

A SELECTION OF TEXTS by Adam Lowe & Charlotte Skene Catling AND A SELECTION OF RECENT PROJECTS The ‘techne’ shelves for Madame de Pompadour in the Frame at Waddesdon Manor, May to October 2019. These shelves contain fragments and samples from a range of projects using diverse materials and processes. factumfoundation.org factum-arte.com 18F0025 The physical reconstruction of the digital restoration of the vandalised sacred cave of Kamukuwaká. A project carried out with the Wauja people of the Upper Xingu, Brazil. © Vilson de Jesus Al-Idrisi’s world map (a recreation) with a test for the facsimile of the burial chamber of Tutankhamun, a facsimile of the Raphael from Lo Spasimo in Palermo remade as a panel painting for its original frame and a recreation of an altar by Piranesi made for The Arts of Piranesi at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini. In June 2019 Carlos Bayod, Guendalina Damone and Otto Lowe taught a five-days course for students from the Photography MA course at ISIA, Urbino. The practical workshop involved recording in Palazzo Grimani with Venetian Heritage and at the Abbazia di San Gregorio during Colnaghi and Charan’s Grand Tour exhibition. 6 7 CONTENTS 1 The Migration of the Aura, or how to explore the original through its facsimiles Bruno Latour & Adam Lowe 11 2 Digital Recording in a Time of Iconoclasm, Tourism and Anti-Ageing Adam Lowe 23 3 Changing attitudes to preservation and the role of non-contact recording technologies in the creation of digital archives for sharing cultural heritage in virtual forms and exact physical facsimiles Adam Lowe 31 4 Tomb recording: Epigraphy, Photography, Digital Imaging, 3D Surveys Adam Lowe 43 5 ‘Wrinkles, Scars, Blotches, Bruises, Fractures, Mutilations, Amputations, Dislocations and Restorations’. -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad. -

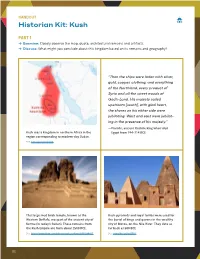

Historian Kit: Kush

HANDOUT Historian Kit: Kush PART 1 → Examine: Closely observe the map, quote, architectural remains and artifacts. → Discuss: What might you conclude about this kingdom based on its remains and geography? “Then the ships were laden with silver, gold, copper, clothing, and everything of the Northland, every product of Syria and all the sweet woods of God’s-Land. His majesty sailed upstream [south], with glad heart, the shores on his either side were jubilating. West and east were jubilat- ing in the presence of his majesty.” — Piankhi, ancient Kushite king who ruled Kush was a kingdom in northern Africa in the Egypt from 744–714 BCE region corresponding to modern-day Sudan. See: http://bit.ly/2KbAl8G This large mud brick temple, known as the Kush pyramids and royal tombs were used for Western Deffufa, was part of the ancient city of the burial of kings and queens in the wealthy Kerma (in today’s Sudan). These remains from city of Meroe, on the Nile River. They date as the Kush Empire are from about 2500 BCE. far back as 500 BCE. See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/waltercallens/3486244425 See: http://bit.ly/3qhZDBl 22 HANDOUT Historian Kit: Kush (continued) This stone carving (1st century BCE) is from the temple of Amun in the ancient city of Naqa. It depicts a kandake (female leader) This piece of gold jewelry was found in the from Meroe. Named Amanishakheto, she tomb of Nubian King Amaninatakilebte stands between a god and goddess. (538–519 BC). See: http://bit.ly/3oGqWFi See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/menesje/47758289472 IMAGE SOURCES Lommes and National Geographic.