Imitation in Aksumite Coinage and Indian Imitations of Aksumite Coins’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beta Samati: Discovery and Excavation of an Aksumite Town Michael J

Beta Samati: discovery and excavation of an Aksumite town Michael J. Harrower1,*, Ioana A. Dumitru1, Cinzia Perlingieri2, Smiti Nathan3,Kifle Zerue4, Jessica L. Lamont5, Alessandro Bausi6, Jennifer L. Swerida7, Jacob L. Bongers8, Helina S. Woldekiros9, Laurel A. Poolman1, Christie M. Pohl10, Steven A. Brandt11 & Elizabeth A. Peterson12 The Empire of Aksum was one of Africa’smost influential ancient civilisations. Traditionally, most archaeological fieldwork has focused on the capital city of Aksum, but recent research at the site of Beta Samati has investigated a contempor- aneous trade and religious centre located between AksumandtheRedSea.Theauthorsoutlinethe discovery of the site and present important finds from the initial excavations, including an early basilica, inscriptions and a gold intaglio ring. From daily life and ritual praxis to international trade, this work illuminates the role of Beta Samati as an administrative centre and its signifi- cance within the wider Aksumite world. Keywords: Africa, Ethiopia, Aksum, ancient trade, ancient states 1 Department of Near Eastern Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Gilman 113, 3400 North Charles Street, Balti- more, MD 21218, USA 2 Center for Digital Archaeology, 555 Northgate #270, San Rafael, CA 94903, USA 3 Life Design Lab, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 4 Archaeology and Heritage Management, P.O. Box 1010, Aksum University, Aksum, Ethiopia 5 Department of Classics, Yale University, 344 College Street, P.O. Box 208266, New Haven, CT 06520, -

Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa This simulation, while focused around the Ethiopia-Eritrea border conflict, is not an attempt to resolve that conflict: the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) already has a peace plan on the table to which the two parties in conflict have essentially agreed. Rather, participants are asked, in their roles as representatives of OAU member states, to devise a blueprint for preventing the Ethiopian-Eritrean conflict from spreading into neighboring countries and consuming the region in even greater violence. The conflict, a great concern particularly for Somalia and Sudan where civil wars have raged for years, has thrown regional alliances into confusion and is increasingly putting pressure on humanitarian NGOs and other regional parties to contain the conflict. The wars in the Horn of Africa have caused untold death and misery over the past few decades. Simulation participants are asked as well to deal with the many refugees and internally displaced persons in the Horn of Africa, a humanitarian crisis that strains the economies – and the political relations - of the countries in the region. In their roles as OAU representatives, participants in this intricate simulation witness first-hand the tremendous challenge of trying to obtain consensus among multiple actors with often competing agendas on the tools of conflict prevention. Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn -

Visually Engaging and Student-Friendly World History Survey CRAIG 4Tlc Sc 8/7/08 2:24 PM Page 2

CRAIG_4tlc_sc 8/7/08 2:24 PM Page 1 Preview Chapter 5 Inside! A visually engaging and student-friendly world history survey CRAIG_4tlc_sc 8/7/08 2:24 PM Page 2 Acclaimed by instructors and students for its new approach to understanding the past, the new Fourth Edition of the Teaching and Learning Classroom Edition of THE HERITAGE OF WORLD CIVILIZATIONS provides even more pathways for learning world history. Albert M. Craig This updated edition includes: Harvard University ■ New “Global Perspective” essays that William A. Graham help students place material into a wider Harvard University framework and see connections and parallels in world history Donald M. Kagan Yale University ■ Expanded coverage of prehistory, Africa, Steven Ozment East Asia, and the Middle East Harvard University Frank M. Turner ■ An all-new design, an expanded map program, Yale University and critical thinking questions that enable students to visualize important information as they read CRAIG_4tlc_sc 8/7/08 2:24 PM Page 3 Part I—The History of Civilization 19. East Asia in the Late Traditional Era Brief Contents 20. State-Building and Society in Early 1. Birth of Civilization Modern Europe 2. The Four Great Revolutions in Thought 21. The Last Great Islamic Empires, and Religion 1500–1800 Part II—Empires and Cultures Part V—Enlightenment and Revolution of the Ancient World in the West 3. Greek and Hellenistic Civilization 22. The Age of European Enlightenment 4. Iran, India, and Inner Asia to 200 c.e. 23. Revolutions in the Transatlantic World 5. Africa: Early History to 1000 c. e. 24. Political Consolidation in Nineteenth- 6. -

Identity in Ethiopia: the Oromo from the 16Th to the 19Th Century

IDENTITY IN ETHIOPIA: THE OROMO FROM THE 16 TH TO THE 19 TH CENTURY By Cherri Reni Wemlinger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Washington State University Department of History August 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of Cherri Reni Wemlinger find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Chair ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT It is a pleasure to thank the many people who made this thesis possible. I would like to acknowledge the patience and perseverance of Heather Streets and her commitment to excellence. As my thesis chair she provided guidance and encouragement, while giving critical advice. My gratitude for her assistance goes beyond words. Thanks are also due to Candice Goucher, who provided expertise in her knowledge of Africa and kind encouragement. She was able to guide my thoughts in new directions and to make herself available during the crunch time. I would like to thank David Pietz who also served on my committee and who gave of his time to provide critical input. There are several additional people without whose assistance this work would have been greatly lacking. Thanks are due to Robert Staab, for his encouragement, guidance during the entire process, and his willingness to read the final product. Thank you to Lydia Gerber, who took hours of her time to give me ideas for sources and fresh ways to look at my subject. Her input was invaluable to me. -

PERSIANS, PORTS, and PEPPER the Red Sea Trade in Late Antiquity

!"#$%&'$()!*#+$()&',)!"!!"# +-.)#./)$.0)+10/.)23)405.)&35267258 91803)40//: &)5-.:2:):7;<255./)5= )5-.)>0?7@58)=A)B10/705.)03/)!=:5/=?5=10@)$57/2.: )23)C01520@)A7@A2@@<.35)=A)5-.)1.6721.<.35:)A=1)5-. )D&)/.E1..)23)F@0::2?0@)$57/2.: ,.C015<.35)=A)F@0::2?:)03/)#.@2E2=7:)$57/2.: >0?7@58)=A)&15: G32H.1:258)=A)*550I0 J)91803)40//:()*550I0()F030/0()KLMN &;:510?5 !"#$#%"&'%(##)%&)%*)+$#&'#,%*)-#$#'-%*)%./0#1'%+/))#+-*/)'%2*-"%-"#%3&$%4&'-%/5#$%-"#%+/6$'#%/7% -"#%8&'-%9:%;#&$'<%!"*'%"&'%$#'68-#,%*)%-"#%=6(8*+&-*/)%/7%0&);%&$-*+8#'%&),%0/)/>$&="'%&(/6-%-"#% ./0&)%*)5/85#0#)-%*)%-"#%.#,%?#&%2"*+"%2&'%-"#%@#;%0&$*-*0#%$#>*/)%8*)@*)>%-"#%3&$%4&'-%2*-"%-"#% A#'-<%!"*'%-"#'*'%';)-"#'*B#'%-"#%$#+#)-%'+"/8&$'"*=%/)%-"#%.#,%?#&%-$&,#%*)%C&-#%D)-*E6*-;%(;%0#$>*)>% &88%/7%-"#%0/'-%6=%-/%,&-#%*)7/$0&-*/)%*)-/%&%+/)+*'#%)&$$&-*5#<%F)%/$,#$%-/%&++/0=8*'"%-"*'G%-"$##%0&H/$% '/6$+#'%/7%*)7/$0&-*/)%"&5#%(##)%&)&8;B#,<%3*$'-8;G%-"#%"*'-/$*+&8%-*0#%7$&0#%/7%&88%/7%-"#%0&H/$%$#>*/)'% /7%-"#%.#,%?#&%*)+86,*)>%4>;=-G%D@'60G%&),%I*0;&$%"&5#%(##)%8&*,%/6-%*)%&%'-$&*>"-%7/$2&$,%)&$$&-*5#<% !"*'%/77#$'%-"#%0/'-%=#$-*)#)-%(&+@>$/6),%*)7/$0&-*/)%7/$%-"#%,#5#8/=0#)-%/7%.#,%?#&%-$&,#<%?#+/),8;G% -"#%0/'-%6=%-/%,&-#%&$+"&#/8/>*+&8%#5*,#)+#%"&'%(##)%*)+/$=/$&-#,%*)-/%&%,#'+$*=-*/)%/7%-"#%&)+*#)-% 0&$*-*0#%-$&,#%*)7$&'-$6+-6$#%/7%-"#%.#,%?#&%&),%F),*&)%J+#&)<%!"#%&$+"&#/8/>*+&8%#5*,#)+#%($/&,#)'% /6$%@)/28#,>#%/7%-"#%$/&,'%-"$/6>"%-"#%4&'-#$)%K#'#$-%/7%4>;=-G%-"#%=/$-'%/7%-"#%.#,%?#&G%&),%-"#% ,#5#8/=0#)- % /7 % -"# % F),*&) % '6(+/)-*)#)- % 0/$# % >#)#$&88;<%!"*$,8;G% -"*' % -

Thekingdomofaksum Andeastafricantrade

199-202-0208s2 10/11/02 3:45 PM Page 199 TERMS & NAMES 2 • Aksum The Kingdom of Aksum • Adulis • Ezana and East African Trade MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW The kingdom of Aksum became an Ancient Aksum, which is now Ethiopia, international trading power and is still a center of Eastern Christianity. adopted Christianity. SETTING THE STAGE In the eighth century B.C., before the Nok were spreading their culture throughout West Africa, the kingdom of Kush in East Africa had become powerful enough to conquer Egypt. (See Chapter 4.) However, fierce Assyrians swept into Egypt during the next century and drove the Kushite pharaohs south. Kush nev- ertheless remained a powerful kingdom for over 1,000 years—until it was conquered by another even more powerful kingdom. The Rise of the Kingdom of Aksum The kingdom that arose was Aksum (AHK•soom). It was located south of Kush on a rugged plateau on the Red Sea, in what is now Eritrea and Ethiopia. A legend traces the founding of the kingdom of Aksum and the Ethiopian royal dynasty to the son of King Solomon of ancient Israel and the Queen of Sheba. That dynasty includes the 20th-century ruler Haile Selassie. In fact, the history of Aksum may have begun as early as 1000 b.c., when Arab peoples crossed the Red Sea into Africa. There they mingled with Kushite herders and farmers and passed along their written language, Ge’ez (GEE•ehz). They also Mediterranean Aksum, A.D. 300–700 shared their skills of working stone and Sea building dams and aqueducts. -

The Aksumites in South Arabia: an African Diaspora of Late Antiquity

Chapter 11 The Aksumites in South Arabia: An African Diaspora of Late Antiquity George Hatke 1 Introduction Much has been written over the years about foreign, specifically western, colo- nialism in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as about the foreign peoples, western and non-western alike, who have settled in sub-Saharan Africa during the modern period. However, although many large-scale states rose and fell in sub- Saharan Africa throughout pre-colonial times, the history of African imperial expansion into non-African lands is to a large degree the history of Egyptian invasions of Syria-Palestine during Pharaonic and Ptolemaic times, Carthagin- ian (effectively Phoenician) expansion into Sicily and Spain in the second half of the first millennium b.c.e, and the Almoravid and Almohad invasions of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. However, none of this history involved sub-Saharan Africans to any appreciable degree. Yet during Late Antiquity,1 Aksum, a sub-Saharan African kingdom based in the northern Ethi- opian highlands, invaded its neighbors across the Red Sea on several occasions. Aksum, named after its capital city, was during this time an active participant in the long-distance sea trade linking the Mediterranean with India via the Red Sea. It was a literate kingdom with a tradition of monumental art and ar- chitecture and already a long history of contact with South Arabia. The history of Aksumite expansion into, and settlement in, South Arabia can be divided into two main periods. The first lasts from the late 2nd to the late 3rd century 1 Although there is disagreement among scholars as to the chronological limits of “Late Antiq- uity”—itself a modern concept—the term is, for the purposes of the present study, used to refer to the period from ca. -

AKSUM Ancient East African Empire

7 AKSUM Ancient East African Empire 950L BY DAVID BAKER, ADAPTED BY NEWSELA The Aksum Empire was the result of two world hubs sharing their collective learning about agriculture. It rose to become a great power in the ancient world. The key to its rise was the crucial link it formed between East and West on the supercontinent of Afro-Eurasia. EAST AFRICA Copper and bronze were rare in the region, so they did not go through a bronze age. Instead, they transitioned directly to iron. Some people in the region still foraged with- East Africa was the cradle of our species. For millions of years, many of our hominine out domesticating anything. However, the knowledge transmitted from Southwest Asia ancestors roamed across the land. It is ultimately the homeland of every human being and Egypt created a mixture of the two lifeways of foraging and agriculture. To the spread across the planet. Additionally, East Africa was the region that birthed one of south, the rest of Africa would transition to agriculture much more slowly. But East the mightiest of African civilizations: the Aksum Empire. At its height in the third cen- Africa was jolted by two major hubs into the agrarian era. tury CE, some ancient writers considered it one of the four great powers of the world, alongside Rome, Persia, and China. Thanks to its position in the web of collective By 1000 BCE, hunting and gathering was on the decline. More and more people were learning in Afro-Eurasia, it rose to become one of the most complex agrarian civiliza- farming. -

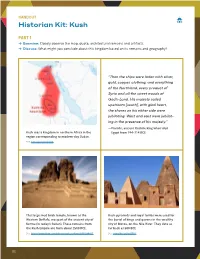

Historian Kit: Kush

HANDOUT Historian Kit: Kush PART 1 → Examine: Closely observe the map, quote, architectural remains and artifacts. → Discuss: What might you conclude about this kingdom based on its remains and geography? “Then the ships were laden with silver, gold, copper, clothing, and everything of the Northland, every product of Syria and all the sweet woods of God’s-Land. His majesty sailed upstream [south], with glad heart, the shores on his either side were jubilating. West and east were jubilat- ing in the presence of his majesty.” — Piankhi, ancient Kushite king who ruled Kush was a kingdom in northern Africa in the Egypt from 744–714 BCE region corresponding to modern-day Sudan. See: http://bit.ly/2KbAl8G This large mud brick temple, known as the Kush pyramids and royal tombs were used for Western Deffufa, was part of the ancient city of the burial of kings and queens in the wealthy Kerma (in today’s Sudan). These remains from city of Meroe, on the Nile River. They date as the Kush Empire are from about 2500 BCE. far back as 500 BCE. See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/waltercallens/3486244425 See: http://bit.ly/3qhZDBl 22 HANDOUT Historian Kit: Kush (continued) This stone carving (1st century BCE) is from the temple of Amun in the ancient city of Naqa. It depicts a kandake (female leader) This piece of gold jewelry was found in the from Meroe. Named Amanishakheto, she tomb of Nubian King Amaninatakilebte stands between a god and goddess. (538–519 BC). See: http://bit.ly/3oGqWFi See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/menesje/47758289472 IMAGE SOURCES Lommes and National Geographic. -

Ethiopia: Muslims in a “Christian Nation”

CHAPTER 8 Ethiopia: Muslims in a “Christian Nation” Another area of Africa with an old regional identity is Ethiopia. Not so much the Ethiopia of the twentieth century, which comprised most of the horn of Africa, but the mountainous zones of the north and west, which have high rainfall and form the main watersheds of the Nile River. This smaller zone is sometimes called Abyssinia (“Habash” for Arabic speakers living in the Middle East). In this instance the associated religious identity is Christian, not Muslim. For centuries Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, and European people have ascribed a Christian identity to the area. Ethiopia was of- ten associated with the Prester John of medieval legend, the Christian kingdom that lived “behind” the lands of Islam and would join with Eu- ropean Christians in a world crusade, as discussed in Chapter 6. This ascription was not completely erroneous, for since the fourth century some Ethiopians have been Christian, in the form of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and have been writing chronicles and letters to communicate that identity. More recently the army of Ethiopia won a signal victory against European invaders and thereby guarded their independence, whereas the rest of Africa was coming under colonial rule. Emperor Meni- lik’s triumph over the Italians at Adwa in 1896 won him undying fame in Africa and the African diaspora and helped to diffuse the association of Ethiopia and Christianity throughout the world. So we find “Ethiopian” Christian churches, usually constituted by Africans and African Americans, all over the globe today. They are rarely Ethiopian Orthodox churches, in terms of ritual or obedience, but Copyright © 2004. -

The Battle for the Battle of Adwa: Collective Identity and Nation- Building

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2020 The Battle For The Battle of Adwa: Collective Identity and Nation- Building Joseph A. Steward CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/836 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Battle for The Battle of Adwa: Collective Identity and Nation-Building Joseph Steward May 2020 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York COLIN POWELL SCHOOL FOR CIVIC AND GLOBAL LEADERSHIP Thesis Advisor: Professor Nicolas Rush Smith Second Reader: Professor Jean Krasno “I beg your majesty to defend me against everyone as I don’t know what European kings will say about this. Let others know that this region is ours.” - Emperor Menelik II Abstract On March 1st, 1896, an Ethiopian army lead by Emperor Menelik II dealt a shocking defeat to the invading Italian forces in the Battle of Adwa. In victory, Menelik was able to exert his authority over a vast territory which included both the historical, ancient kingdoms of the northern and central parts of Ethiopia, and also the vast, resource-rich territories in the west and south which he had earlier conquered. The egalitarian nature of the victory united the various peoples of Ethiopia against a common enemy, giving Menelik the opportunity to create a new Ethiopian nation. -

The Kingdom of Aksum

3 The Kingdom of Aksum MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES POWER AND AUTHORITY The Ancient Aksum, which is now • Aksum •Ezana kingdom of Aksum became an Ethiopia, is still a center of the • Adulis •terraces international trading power and Ethiopian Orthodox Christian adopted Christianity. Church. SETTING THE STAGE While migrations were taking place in the southern half of Africa, they were also taking place along the east coast. Arab peoples crossed the Red Sea into Africa perhaps as early as 1000 B.C. There they intermarried with Kushite herders and farmers and passed along their written language, Ge’ez (GEE•ehz). The Arabs also shared their skills of working stone and building dams and aqueducts. This blended group of Africans and Arabs would form the basis of a new and powerful trading kingdom. The Rise of the Kingdom of Aksum TAKING NOTES Summarizing List the You learned in Chapter 4 that the East African kingdom of Kush became power- achievements of Aksum. ful enough to push north and conquer Egypt. During the next century, fierce Assyrians swept into Egypt and drove the Kushite pharaohs south. However, Kush remained a powerful kingdom for over 1,000 years. Finally, a more powerful kingdom arose and conquered Kush. That kingdom was Aksum Aksum's (AHK•soom). It was located south of Kush on a rugged plateau on the Red Sea, Achievements in what are now the countries of Eritrea and Ethiopia. (See map on page 226.) In this area of Africa, sometimes called the Horn of Africa, Arab traders from across the Red Sea established trading settlements.