The Battle for the Battle of Adwa: Collective Identity and Nation- Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Beta Samati: Discovery and Excavation of an Aksumite Town Michael J

Beta Samati: discovery and excavation of an Aksumite town Michael J. Harrower1,*, Ioana A. Dumitru1, Cinzia Perlingieri2, Smiti Nathan3,Kifle Zerue4, Jessica L. Lamont5, Alessandro Bausi6, Jennifer L. Swerida7, Jacob L. Bongers8, Helina S. Woldekiros9, Laurel A. Poolman1, Christie M. Pohl10, Steven A. Brandt11 & Elizabeth A. Peterson12 The Empire of Aksum was one of Africa’smost influential ancient civilisations. Traditionally, most archaeological fieldwork has focused on the capital city of Aksum, but recent research at the site of Beta Samati has investigated a contempor- aneous trade and religious centre located between AksumandtheRedSea.Theauthorsoutlinethe discovery of the site and present important finds from the initial excavations, including an early basilica, inscriptions and a gold intaglio ring. From daily life and ritual praxis to international trade, this work illuminates the role of Beta Samati as an administrative centre and its signifi- cance within the wider Aksumite world. Keywords: Africa, Ethiopia, Aksum, ancient trade, ancient states 1 Department of Near Eastern Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Gilman 113, 3400 North Charles Street, Balti- more, MD 21218, USA 2 Center for Digital Archaeology, 555 Northgate #270, San Rafael, CA 94903, USA 3 Life Design Lab, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 4 Archaeology and Heritage Management, P.O. Box 1010, Aksum University, Aksum, Ethiopia 5 Department of Classics, Yale University, 344 College Street, P.O. Box 208266, New Haven, CT 06520, -

Download/Documents/AFR2537302021ENGLISH.PDF

“I DON’T KNOW IF THEY REALIZED I WAS A PERSON” RAPE AND OTHER SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE CONFLICT IN TIGRAY, ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustrator: Nala Haileselassie) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 25/4569/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 9 4. SEXUAL VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS IN TIGRAY 12 GANG RAPE, INCLUDING OF PREGNANT WOMEN 12 SEXUAL SLAVERY 14 SADISTIC BRUTALITY ACCOMPANYING RAPE 16 BEATINGS, INSULTS, THREATS, HUMILIATION 17 WOMEN SEXUALLY ASSAULTED WHILE TRYING TO FLEE THE COUNTRY 18 5. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

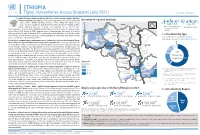

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

The 1991 Transitional Charter of Ethiopia: a New Application of the Self-Determination Principle, 28 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 28 | Issue 2 1996 The 1991 rT ansitional Charter of Ethiopia: A New Application of the Self-Determination Principle Aaron P. Micheau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Aaron P. Micheau, The 1991 Transitional Charter of Ethiopia: A New Application of the Self-Determination Principle, 28 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 367 (1996) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol28/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE 1991 TRANSITIONAL CHARTER OF ETHIOPIA: A NEW APPLICATION OF THE SELF-DETERMINATION PRINCIPLE? Aaron P. Micheau* INTRODUCTION EMERGENT AND RE-EMERGENT NATIONALISM seem to have taken center stage in a cast of new worldwide political trends. Nationalism has appeared in many forms across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America, and is considered the primary threat to peace in the current world order. [Tihe greatest risks of starting future wars will likely be those associated with ethnic disputes and the new nationalism that seems to be increasing in many areas .... The former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia are being tom by ethnic desires for self-government; ethnic-like religious demands are fueling new nationalism in Israel and the Islamic nations; ethnic pressures are reasserting themselves again in Canadian politics; and throughout the Pacific Basin .. -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published Online: 14 Apr 2013

This article was downloaded by: [US Naval Academy] On: 25 June 2013, At: 06:09 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of the Middle East and Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujme20 The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published online: 14 Apr 2013. To cite this article: Nikolaos Biziouras (2013): The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961), The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 4:1, 21-46 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2013.771419 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

History of Events and Internal Developement. the Example of The

Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies University of Addis Ababa, 1984 Edited by Dr Taddese Beyene Volume 1 isbn — Volume 1: 1 85450 000 7 Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa 1988 Table of Contents Preface Opening Address The New Ethiopia: Major Defining Characteristics. Research Trends in Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University over the last Twenty-Five Years. Prehistory and Archaeology Early Stone Age Cultures in Ethiopia. Alemseged Abbay Les Monuments Gondariens des XVIIe et XVIIIe Steeles. Une Vue d'ensemble. Francis Anfray Le Gisement Paleolithique de Melka-Kunture. Evolution et Culture. Jean Chavaillon A Review of the Archaeological Evidence for the Origins of Food Production in Ethiopia. John Desmond Clark Reflections on the Origins of the Ethiopian Civilization. Ephraim Isaac and Cain Felder Remarks on the Late Prehistory and Early History of Northern Ethiopia. Rodolfo Fattovich History to 1800 Is Näwa Bäg'u an Ethiopian Cross? Ewa Balicka-Witakowska The Ruins of Mertola-Maryam. Stephen Bell Who Wrote "The History of King Sarsa Dengel" - Was it the Monk Bahrey? S. B. Chernetsov Les Affluents de la Rive Droite du Nil dans la Geographie Antique. Jehan Desanges Ethiopian Attitudes towards Europeans until 1750. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski The Ta'ämra 'Iyasus: a study of textual and source-critical problems. S. Gem The Mediterranean Context for the Medieval Rock-Cut Churches of Ethiopia. Michael Gerven Introducing an Arabic Hagiography from Wällo Hussein Ahmed Some Hebrew Sources on the Beta-Israel (Falasha). Steven Kaplan The Problem of the Formation of the Peasant Class in Ethiopia. Yu. M. Kobischanov The Sor'ata Gabr - a Mirror View of Daily Life at the Ethiopian Royal Court in the Middle Ages. -

Ethiopia, the TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at WMU Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU International Conference on African Development Center for African Development Policy Research Archives 8-2001 Ethiopia, The TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Milkias, Paulos, "Ethiopia, The TPLF nda Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor" (2001). International Conference on African Development Archives. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/4 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for African Development Policy Research at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on African Development Archives by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETHIOPIA, TPLF AND ROOTS OF THE 2001 * POLITICAL TREMOR ** Paulos Milkias Ph.D. ©2001 Marianopolis College/Concordia University he TPLF has its roots in Marxist oriented Tigray University Students' movement organized at Haile Selassie University in 1974 under the name “Mahber Gesgesti Behere Tigray,” [generally T known by its acronym – MAGEBT, which stands for ‘Progressive Tigray Peoples' Movement’.] 1 The founders claim that even though the movement was tactically designed to be nationalistic it was, strategically, pan-Ethiopian. 2 The primary structural document the movement produced in the late 70’s, however, shows it to be Tigrayan nationalist and not Ethiopian oriented in its content. -

Productive and Reproductive Performance of Local Cows Under Farmer’S Management in Central Tigray, Ethiopia

Nigerian J. Anim. Sci. 2020 Vol 22 (3): 70-74 (ISSN:1119-4308) © 2020 Animal Science Association of Nigeria (https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjas) available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Productive and reproductive performance of local cows under farmer’s management in central Tigray, Ethiopia Abrha B. H., Niraj K.*, Berihu G., Kiros A. and Gebregiorgis A. G. College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Mob: +251.966675736) Target audience: Ministry of Agriculture, Researchers, Dairy Policy Makers Abstract The study was conducted on 408 indigenous cows maintained under farmer’s management in eight districts of central Tigray, Ethiopia. A total of 208 small-scale dairy farm owners were randomly selected and interviewed with structured questionnaire to obtain information on the productive and reproductive performance of indigenous cows. The results of the study showed that the mean age at first calving (AFC) was 43.3 ±2.7 months, number of services per conception (NSC) was 2.7±0.5, days open (DO) was 201.47±61.21 days, calving interval (CI) was 468.33±71.42 days, lactation length (LL) was 206.17±32.33 days, lactation milk yield (LMY) was 414.65±53.69 litres for indigenous cows. The estimated value for productive and reproductive traits had higher than normal range in indigenous cows. This calls for a planned technical and institutional intervention for improved support services for appropriate breeding programs, improved cows and adequate veterinary health services. Key words: Productive and Reproductive Performance, Local Cows. -

Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa This simulation, while focused around the Ethiopia-Eritrea border conflict, is not an attempt to resolve that conflict: the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) already has a peace plan on the table to which the two parties in conflict have essentially agreed. Rather, participants are asked, in their roles as representatives of OAU member states, to devise a blueprint for preventing the Ethiopian-Eritrean conflict from spreading into neighboring countries and consuming the region in even greater violence. The conflict, a great concern particularly for Somalia and Sudan where civil wars have raged for years, has thrown regional alliances into confusion and is increasingly putting pressure on humanitarian NGOs and other regional parties to contain the conflict. The wars in the Horn of Africa have caused untold death and misery over the past few decades. Simulation participants are asked as well to deal with the many refugees and internally displaced persons in the Horn of Africa, a humanitarian crisis that strains the economies – and the political relations - of the countries in the region. In their roles as OAU representatives, participants in this intricate simulation witness first-hand the tremendous challenge of trying to obtain consensus among multiple actors with often competing agendas on the tools of conflict prevention. Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn of Africa Simulation on Conflict Prevention in the Greater Horn