Starving Tigray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 59 - 18 January 2021

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 59 - 18 January 2021 Europe External Programme with Africa is a Belgium-based Centre of Expertise with in-depth knowledge, publications, and networks, specialised in issues of peace building, refugee protection and resilience in the Horn of Africa. EEPA has published extensively on issues related to movement and/or human trafficking of refugees in the Horn of Africa and on the Central Mediterranean Route. It cooperates with a wide network of Universities, research organisations, civil society and experts from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and across Africa. Reported war situation (as confirmed per 17 January) - According to Sudan Tribune, the head of the Sudanese Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, disclosed that Sudanese troops were deployed on the border as per an agreement with the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, arranged prior to the beginning of the war. - Al-Burhan told a gathering about the arrangements that were made in the planning of the military actions: “I visited Ethiopia shortly before the events, and we agreed with the Prime Minister of Ethiopia that the Sudanese armed forces would close the Sudanese borders to prevent border infiltration to and from Sudan by an armed party.” - Al-Burhan stated: "Actually, this is what the (Sudanese) armed forces have done to secure the international borders and have stopped there." His statement suggests that Abiy Ahmed spoke with him about the military plans before launching the military operation in Tigray. - Ethiopia has called the operation a “domestic law and order” action to respond to domestic provocations, but the planning with neighbours in the region on the actions paint a different picture. -

Download/Documents/AFR2537302021ENGLISH.PDF

“I DON’T KNOW IF THEY REALIZED I WAS A PERSON” RAPE AND OTHER SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE CONFLICT IN TIGRAY, ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustrator: Nala Haileselassie) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 25/4569/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 9 4. SEXUAL VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS IN TIGRAY 12 GANG RAPE, INCLUDING OF PREGNANT WOMEN 12 SEXUAL SLAVERY 14 SADISTIC BRUTALITY ACCOMPANYING RAPE 16 BEATINGS, INSULTS, THREATS, HUMILIATION 17 WOMEN SEXUALLY ASSAULTED WHILE TRYING TO FLEE THE COUNTRY 18 5. -

On Farm Performance Evaluation of Three Local Chicken Ecotypes in Western Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) Vol.5, No.7, 2015 On Farm Performance Evaluation of Three Local Chicken Ecotypes in Western Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia Shishay Markos 1* Berhanu Belay 2 Tadelle Dessie 3 1.Humera Agricultural Research Center of Tigray Agricultural Research Institute, P.O.BOX 492, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia 2.Jimma University College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, P.O.Box 307, Jimma, Ethiopia 3.International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), P.O.BOX, 5689, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract The study aimed to assess performances of three local chicken ecotypes under free scavenging production system in western Tigray. Multi stage sampling procedure was applied for the study, hence three rural weredas, nine kebeles and 385 respondents were selected by purposive, stratified purposive and purposive random sampli ng techniques, respectively. Pretested questionnaire was employed to generate data. Household characteristics w ere analyzed using descriptive statistics and Kruskal Wall’s of SPSS 16 was employed to test qualitative variable proportion difference across agroecologies. Performance traits were analyzed by GLM Procedures of SAS 9.2. Tukey test was used to compare means for significant traits. Significant differences were observed among chicken ecotypes in almost all studied performance traits. Lowland chicken ecotypes earlier to mature sexually, slaughter and onset egg laying in comparison to the other two ecotypes but yielded lower hatchability and egg yield. The overall mean age of sexual maturity of local chicken was 7.19±0.04 and 5.71±0.03 month for female and male respectively. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

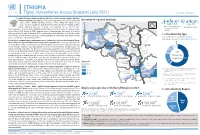

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Household Level Rainwater Harvesting in the Drylands of Northern Ethiopia

AgriFoSe2030 Report 11, 2018 An AgriFoSe2030 Final Report from Theme 2 - Multifunctional landscapes for increased food security Household level rainwater harvesting in the drylands Today more than 800 million people around the of northern Ethiopia: world suffer from chronic hunger and about 2 its role for food and billion from under-nutrition. This failure by humanity is challenged in UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2: “End nutrition security hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture”. The AgriFoSe2030 program directly targets SDG Kassa Teka 2 in low-income countries by translating state- of-the-art science into clear, relevant insights that can be used to inform better practices and Land Resource Management and Environmental Protection, policies for smallholders. College of Dryland Agriculture and Natural Resources, The AgriFoSe2030 program is implemented Mekelle University, Ethiopia by a consortium of scientists from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Lund University, Gothenburg University and Stockholm Environment Institute and is hosted by the platform SLU Global. AgriFoSe2030 The program is funded by the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) with Agriculture for Food Security 2030 a budget of 60 MSEK over a four-year period - Translating science into policy and practice starting in November 2015. News, events and more information are available at www.slu.se/agrifose ISBN: 978-91-576-9598-7 1 Contents Summary 3 Acknowledgements 3 1. Introduction 3 2. Area Description 4 3. Implemented rainwater harvesting technologies (RWHTs) in Tigray 5 3.1. Overview 5 3.2. Description of RWHTs 6 3.2.1. Household ponds 6 3.2.2. -

The Case of Alamata and Atsbi-Wonberta Woredas of Tigray Region

MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF POULTRY: THE CASE OF ALAMATA AND ATSBI-WONBERTA WOREDAS OF TIGRAY REGION M.Sc. Thesis Dawit Gebregziabher January 2010 Haramaya University MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF POULTRY: THE CASE OF ALAMATA AND ATSBI-WONBERTA WOREDAS OF TIGRAY REGION A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics, School of Graduate Studies HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURE (AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS) BY Dawit Gebregziabher January 2010 Haramaya University APPROVAL SHEET SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY As thesis research advisors, we here by certify that we have read and evaluated this thesis prepared, under our guidance, by Dawit Gebregziabher entitled “Market Chain Analysis of Poultry: the case of Alamata and Atsbi Wonberta Woredas of Tigray Region.” We recommend that it be submitted as fulfilling the thesis requirement. Berhanu Gebremedhin (PhD) __________________ ______________ Major Advisor Signature Date Dirk Hoekstra (Mr) __________________ _____________ Co-Advisor Signature Date As member of the Board of Examiners of the M.Sc Thesis Open Defense, we certify that we have read, evaluated the Thesis prepared by Dawit Gebregziabher Mekonen and examine the candidate. We recommend that the Thesis be accepted as fulfilling the Thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Science in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics). DegnetAbebaw (PhD) __________________ _____________ Chair Person Signature Date Adem Kedir (Mr) __________________ _____________ Internal Examiner Signature Date Admasu Shbiru (PhD) __________________ _____________ External Examiner Signature Date ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis manuscript to my family for their moral and encouragement in the study period in particular and throughout my life in general. -

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

20Th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ፳ኛ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ

20th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ኛ ፳ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ Regional and Global Ethiopia – Interconnections and Identities 30 Sep. – 5 Oct. 2018 Mekelle University, Ethiopia Message by Prof. Dr. Fetien Abay, VPRCS, Mekelle University Mekelle University is proud to host the International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (ICES20), the most prestigious conference in social sciences and humanities related to the region. It is the first time that one of the younger universities of Ethiopia has got the opportunity to organize the conference by itself – following the great example set by the French team of the French Centre of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Abeba organizing the ICES in cooperation with Dire Dawa University in 2012, already then with great participation by Mekelle University academics and other younger universities of Ethiopia. We are grateful that we could accept the challenge, based on the set standards, in the new framework of very dynamic academic developments in Ethiopia. The international scene is also diversifying, not only the Ethiopian one, and this conference is a sign for it: As its theme says, Ethiopia is seen in its plural regional and global interconnections. In this sense it becomes even more international than before, as we see now the first time a strong participation from almost all neighboring countries, and other non-Western states, which will certainly contribute to new insights, add new perspectives and enrich the dialogue in international academia. The conference is also international in a new sense, as many academics working in one country are increasingly often nationals of other countries, as more and more academic life and progress anywhere lives from interconnections. -

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region The situation of child marriage in Qewet and Bahir Dar Zurida: a focus on gender roles, parenting and young people’s future perspectives Abeje Berhanu Dereje Tesama Beleyne Worku Almaz Mekonnen Lisa Juanola Anke van der Kwaak University of Addis Ababa & Royal Tropical Institute January 2019 1 Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background of the Yes I Do programme .............................................................................................. 4 1.2 Process of identifying themes for this study ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 Social and gender norms related to child marrige .............................................................................. 5 1.4 Objective of the study ......................................................................................................................... 7 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Description of the study areas ............................................................................................................. 9 2.1.1 Qewet woreda, North Shewa zone.............................................................................................. -

Productive and Reproductive Performance of Local Cows Under Farmer’S Management in Central Tigray, Ethiopia

Nigerian J. Anim. Sci. 2020 Vol 22 (3): 70-74 (ISSN:1119-4308) © 2020 Animal Science Association of Nigeria (https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjas) available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Productive and reproductive performance of local cows under farmer’s management in central Tigray, Ethiopia Abrha B. H., Niraj K.*, Berihu G., Kiros A. and Gebregiorgis A. G. College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Mob: +251.966675736) Target audience: Ministry of Agriculture, Researchers, Dairy Policy Makers Abstract The study was conducted on 408 indigenous cows maintained under farmer’s management in eight districts of central Tigray, Ethiopia. A total of 208 small-scale dairy farm owners were randomly selected and interviewed with structured questionnaire to obtain information on the productive and reproductive performance of indigenous cows. The results of the study showed that the mean age at first calving (AFC) was 43.3 ±2.7 months, number of services per conception (NSC) was 2.7±0.5, days open (DO) was 201.47±61.21 days, calving interval (CI) was 468.33±71.42 days, lactation length (LL) was 206.17±32.33 days, lactation milk yield (LMY) was 414.65±53.69 litres for indigenous cows. The estimated value for productive and reproductive traits had higher than normal range in indigenous cows. This calls for a planned technical and institutional intervention for improved support services for appropriate breeding programs, improved cows and adequate veterinary health services. Key words: Productive and Reproductive Performance, Local Cows. -

Regreening of the Northern Ethiopian Mountains: Effects on Flooding and on Water Balance

PATRICK VAN DAMME THE ROLE OF TREE DOMESTICATION IN GREEN MARKET PRODUCT VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 129-147 REGREENING OF THE NORTHERN ETHIOPIAN MOUNTAINS: EFFECTS ON FLOODING AND ON WATER BALANCE Tesfaalem G. Asfaha (1,2), Michiel De Meyere (2), Amaury Frankl (2), Mitiku Haile (3), Jan Nyssen (2) (1) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia (2) Department of Geography, Ghent University, Belgium (3) Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, Ethiopia The hydro-geomorphology of mountain catchments is mainly determined by vegetation cover. This study was carried out to analyse the impact of vegetation cover dynamics on flooding and water balance in 11 steep (0.27-0.65 m m-1) catchments of the western Rift Valley escarpment of Northern Ethiopia, an area that experienced severe deforestation and degradation until the first half of the 1980s and considerable reforestation thereafter. Land cover change analysis was carried out using aerial photos (1936,1965 and 1986) and Google Earth imaging (2005 and 2014). Peak discharge heights of 332 events and the median diameter of the 10 coarsest bedload particles (Max10) moved in each event in three rainy seasons (2012-2014) were monitored. The result indicates a strong re- duction in flooding (R2 = 0.85, P<0.01) and bedload sediment supply (R2 = 0.58, P<0.05) with increas- ing vegetation cover. Overall, this study demonstrates that in reforesting steep tropical mountain catchments, magnitude of flooding, water balance and bedload movement is strongly determined by vegetation cover dynamics.