Minority and Indigenous Trends 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minority Rights

Fact Sheet No.18 (Rev.1), Minority Rights Contents: o Introduction o Provisions for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Persons belonging to Minorities o The Implementation of Special Rights and the Promotion of further Measures for the Protection of Minorities o Complaints Procedures o Early Warning Mechanisms o Role of Non-Governmental Organizations o The Way Ahead Annex I: Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (Adopted by General Assembly resolution 47/135 of 18 December 1992) Introduction "... The promotion and protection of the rights of persons belonging to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities contribute to the political and social stability of States in which they live" (Preamble of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities) (1) Almost all States have one or more minority groups within their national territories, characterized by their own ethnic, linguistic or religious identity which differs from that of the majority population. Harmonious relations among minorities and between minorities and majorities and respect for each group's identity is a great asset to the multi-ethnic and multi-cultural diversity of our global society. Meeting the aspirations of national, ethnic, religious and linguistic groups and ensuring the rights of persons belonging to minorities acknowledges the dignity and equality of all individuals, furthers participatory development, and thus contributes to the lessening of tensions among groups and individuals. These factors are a major determinant etc. of stability and peace. The protection of minorities has not, until recently, attracted the same level of attention as that accorded other rights which the United Nations considered as having a greater urgency. -

Stevenson Memorial Tournament 2018 Edited by Jordan

Stevenson Memorial Tournament 2018 Edited by Jordan Brownstein, Ewan MacAulay, Kai Smith, and Anderson Wang Written by Olivia Lamberti, Young Fenimore Lee, Govind Prabhakar, JinAh Kim, Deepak Moparthi, Arjun Nageswaran, Ashwin Ramaswami, Charles Hang, Jacob O’Rourke, Ali Saeed, Melanie Wang, and Shamsheer Rana With many thanks to Brad Fischer, Ophir Lifshitz, Eric Mukherjee, and various playtesters Packet 2 Tossups: 1. An algorithm devised by this person uses Need, Allocated, and Available arrays to keep the system in a safe state when allocating resources. This scientist, Hoare, and Dahl authored the book Structured Programming, which promotes a paradigm that this man also discussed in a handwritten manuscript that popularized the phrase “considered harmful.” Like Prim’s algorithm, an algorithm by this person can achieve the optimal runtime of big-O of E plus V-log-V using a (*) Fibonacci heap. This man expanded on Dekker’s algorithm to propose a solution to the mutual exclusion problem using semaphores. The A-star algorithm uses heuristics to improve on an algorithm named for this person, which can fail with negative-weight edges. For 10 points, what computer scientist’s namesake algorithm is used to find the shortest path in a graph? ANSWER: Edsger Wybe Dijkstra [“DIKE-struh”] <DM Computer Science> 2. A design from this city consists of a window with a main panel and two narrow double-hung windows on both sides. The DeWitt-Chestnut Building in this city introduced the framed tube structure created by an architect best known for working in this city. Though not in Connecticut, a pair of apartment buildings in this city have façades with grids of steel and glass curtain walls and are called the “Glass House” buildings. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Approved in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic June 14, 2016 During the Forty-sixth Ordinary Period of Sessions of the OAS General Assembly AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES Organization of American States General Secretariat Secretariat of Access to Rights and Equity Department of Social Inclusion 1889 F Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 | USA 1 (202) 370 5000 www.oas.org ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 More rights for more people OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Organization of American States. General Assembly. Regular Session. (46th : 2016 : Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) : (Adopted at the thirds plenary session, held on June 15, 2016). p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.P) ; (OAS. Official records ; OEA/ Ser.D) ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 1. American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2016). 2. Indigenous peoples--Civil rights--America. 3. Indigenous peoples--Legal status, laws, etc.--America. I. Organization of American States. Secretariat for Access to Rights and Equity. Department of Social Inclusion. II. Title. III. Series. OEA/Ser.P AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) OEA/Ser.D/XXVI.19 AG/RES. 2888 (XLVI-O/16) AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES (Adopted at the third plenary session, held on June 15, 2016) THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, RECALLING the contents of resolution AG/RES. 2867 (XLIV-O/14), “Draft American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” as well as all previous resolutions on this issue; RECALLING ALSO the declaration “Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas” [AG/DEC. -

Concept Note and Agenda REGIONAL MEETING on ETHNICITY and HEALTH in the AMERICAS 7-8 December 2015 Introduction Available Data

Concept note and agenda REGIONAL MEETING ON ETHNICITY AND HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS 7-8 December 2015 Introduction Available data indicates that indigenous and afrodescent peoples are amongst the most marginalized populations of the region, encountering considerable challenges with regards to social and health conditions and with higher levels of rurality or urban marginality, unemployment, poverty, and illiteracy. They have less access to, and lower utilization of, health services, particularly quality health services, as compared to the rest of the population. Therefore, their health outcomes are poorer, presenting greater morbidity and mortality both from communicable and chronic diseases as well as external causes. Since 1993, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) approved significant Resolutions to address these challenges and to advance the work on ethnicity and health in the region. In 1993, Member States reached consensus in recognizing the deficits in both living conditions and health among the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Resolution 1 aimed to implement the SAPIA initiative (Health of the Indigenous Peoples Initiative of the Americas) and was reinforced by other two Resolutions on indigenous peoples approved in 1997 and 2006 2. The Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage, approved in 2014, specifically refers to indigenous and afro-descendant as some of the most affected groups facing problems of exclusion and lack of access to appropriate quality services. In addition, at global levels, there has been increasing attention to indigenous and afrodescent issues: the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) was held at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2014. -

Marine-Oriented Sama-Bajao People and Their Search for Human Rights

Marine-Oriented Sama-Bajao People and Their Search for Human Rights AURORA ROXAS-LIM* Abstract This research focuses on the ongoing socioeconomic transformation of the sea-oriented Sama-Bajao whose sad plight caught the attention of the government authorities due to the outbreak of violent hostilities between the armed Bangsa Moro rebels and the Armed Forces of the Philippines in the 1970s. Among hundreds of refugees who were resettled on land, the Sama- Bajao, who avoid conflicts and do not engage in battles, were displaced and driven further out to sea. Many sought refuge in neighboring islands mainly to Sabah, Borneo, where they have relatives, trading partners, and allies. Massive displacements of the civilian populations in Mindanao, Sulu, and Tawi- Tawi that spilled over to outlying Malaysia and Indonesia forced the central government to take action. This research is an offshoot of my findings as a volunteer field researcher of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and the National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP) to monitor the implementation of the Indigenous People’s Rights to their Ancestral Domain (IPRA Law RA 8371 of 1997). Keywords: inter-ethnic relations, Sama-Bajao, Taosug, nomadism, demarcation of national boundaries, identity and citizenship, human rights of indigenous peoples * Email: [email protected] V olum e 18 (2017) Roxas-Lim Introduction 1 The Sama-Bajao people are among the sea-oriented populations in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Sama-Bajao are mentioned together and are often indistinguishable from each other since they speak the same Samal language, live in close proximity with each other, and intermarry. -

The Bank's Policy on Indigenous Peoples

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK THE BANK’S POLICY ON INDIGENOUS PEOPLES April 1998 2 ABBREVIATIONS COSS Country Operational Strategy Study DMC Developing Member Country IDB Inter-American Development Bank ILO International Labour Organisation ISA Initial Social Assessment OESD Office of Environment and Social Development PPTA Project Preparatory Technical Assistance RRP Report and Recommendation of the President UNICED United Nation Conference on Environment Programme UNDP United Nations Development Programme TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. DEFINITION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 2 III. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND DEVELOPMENT 3 A. Indigenous Peoples and Development 4 B. Goals and Objectives of Development 4 C. Culture and Development 4 IV. LAWS AND CONVENTIONS AFFECTING INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 4 A. National Laws and Practices 4 B. International Conventions and Declarations 5 C. Practices of Other International Institutions 6 V. POLICY OBJECTIVES, PROCESSES, AND APPROACHES 7 A. Policy Objectives 7 B. Operational Processes 8 C. Operational Approaches 9 VI. ORGANIZATIONAL IMPLICATIONS AND RESOURCE REQUIREMENTS 10 A. Organizational Implications 10 B. Resource Requirements. 11 VII. POLICY ON INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 12 A. A Policy on Indigenous Peoples in Bank Operations 12 B. Policy Elements 12 1 I. INTRODUCTION 1. Indigenous peoples1 can be regarded as one of the largest vulnerable segments of society. While differing significantly in terms of culture, identity, economic systems, and social institutions, indigenous peoples as a whole most often reflect specific disadvantage in terms of social indicators, economic status, and quality of life. Indigenous peoples often are not able to participate equally in development processes and share in the benefits of development, and often are not adequately represented in national social, economic, and political processes that direct development. -

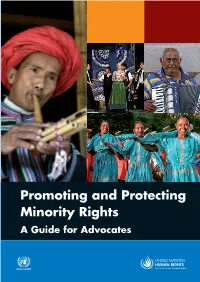

Promoting and Protecting Minority Rights a Guide for Advocates

Promoting and Protecting Minority Rights A Guide for Advocates Designed and printed by the Publishing Service, United Nations publications United Nations, Geneva — GE.13-40538 Sales No. E.13.XIV.1 July 2013 — 3,452 — HR/PUB/12/7 ISBN 978-92-1-154197-7 Promoting and Protecting Minority Rights A Guide for Advocates Geneva and New York, 2012 ii PROMOTING AND PROTECTING MINORITY RIGHTS Note The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a figure indicates a reference to a United Nations document. HR/PUB/12/7 Sales No. E.13.XIV.1 ISBN 978-92-1-154197-7 eISBN 978-92-1-056280-5 © 2012 United Nations All worldwide rights reserved Minority rights focus in the United Nations iii Foreword I am delighted that this publication, Promoting and Protecting Minority Rights: A Guide for Minority Rights Advocates, comes before you as we celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities. This anniversary gives us the opportunity to look back on the 20 years of promoting the Declaration and use that experience to plan and strategize for the future, to decide how best to bring this Declaration further to the fore of human rights discussions taking place all over the world and discuss its implementation. -

Editor's Note: Indigenous Communities and COVID-19

Volume 4, Issue 1 (October 2015) Volume 9, Issue 3 (2020) http://w w w.hawaii.edu/sswork/jisd https://ucalgary.ca/journals/jisd http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/ E-ISSN 2164-9170 handle/10125/37602 pp. 1-3 E-ISSN 2164-9170 pp. 1-15 Editor’s Note: Indigenous Communities and COVID-19: Impact and Implications R eaching Harmony Across Indigenous and Mainstream Peter Mataira ReHawaiisear cPacifich Co nUniversitytexts: A Collegen Em eofr gHealthent N andar rSocietyative CaPaulatherin eMorelli E. Burn ette TuUniversitylane U niver sofity Hawai‘i at Mānoa Michael S. Spencer ShUniversityanondora B ioflli oWashingtont Wa shington University i n St. Louis As the editors we honor those who have contributed to this special issue, Indigenous CommunitiesKey Words and COVID-19: Impact and Implications. In this time of great uncertainty and unrest Indigenous r esearch • power • decolonizing research • critical theory we felt compelled to seek a call for papers that would examine aspects of our traditional cultures focusedAbstra specificallyct on COVID-19 and its disruptions to the dimensions of our wellbeing and the Research with indigenous communities is one of the few areas of research restoration of wellness. This virus has impacted every individual and family on this planet, and, has encompassing profound controversies, complexities, ethical responsibilities, and helpedhistor iccoalesceal contex tthe of pervasiveexploitat ion intersectional and harm. O fstrugglesten this c oofm pIndigenouslexity becom ePeopless . overwhTheelmi narticlesgly appa rselectedent to th eare ea rcompellingly career resea inrch theirer wh oability endeav toors castto m lightake over the shadows of discord meaningful contributions to decolonizing research. Decolonizing research has the andca pairaci tofy t oconspiracy be a cat alyst fsurroundingor the improve dthis wel lpandemic.being and po sTheyitive so acknowledgecial change amon thatg the grief and anguish buried beneathindigen otheus csoilomm ofun intergenerationalities and beyond. -

Late Glacial and Holocene Avulsions of the Rio Pastaza Megafan (Ecuador- Peru): Frequency and Controlling Factors

Late Glacial and Holocene avulsions of the Rio Pastaza Megafan (Ecuador- Peru): frequency and controlling factors Carolina Bernal, Frédéric Christophoul, José Darrozes, Jean-Claude Soula, Patrice Baby, José Burgos To cite this version: Carolina Bernal, Frédéric Christophoul, José Darrozes, Jean-Claude Soula, Patrice Baby, et al.. Late Glacial and Holocene avulsions of the Rio Pastaza Megafan (Ecuador- Peru): frequency and con- trolling factors. International Journal of Earth Sciences, Springer Verlag, 2011, 100 (1759-1782), pp.10.1007/s00531-010-0555-9. 10.1007/s00531-010-0555-9. hal-00536576v3 HAL Id: hal-00536576 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00536576v3 Submitted on 16 Nov 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Late Glacial and Holocene avulsions of the Rio Pastaza Megafan (Ecuador-Peru): Frequency and controlling factors Carolina Bernal, Frédéric Christophoul, José Darrozes, jean-Claude Soula, Patrice Baby, José Burgos. International Journal of Earth Sciences (2011), 100, 1759-1782 DOI 10.1007/s00531-010-0555-9 hal-00536576 factors, post-LGM, tectonics C. Bernal, F. Christophoul, J-C. Soula, J. Darrozes and P. Baby, UMR 5563 GET, Université de Toulouse-CNRS-IRD-OMP- Introduction CNES,14 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France. -

Mining Conflicts and Indigenous Peoples in Guatemala

Mining Conflicts and Indigenous Peoples in Guatemala 1 Introduction I Mining Conflicts and Indigenous Indigenous and Conflicts Mining in Guatemala Peoples Author: Joris van de Sandt September 2009 This report has been commissioned by the Amsterdam University Law Faculty and financed by Cordaid, The Hague. Academic supervision by Prof. André J. Hoekema ([email protected]) Guatemala Country Report prepared for the study: Environmental degradation, natural resources and violent conflict in indigenous habitats in Kalimantan-Indonesia, Bayaka-Central African Republic and San Marcos-Guatemala Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to all those who gave me the possibility to complete this study. Most of all, I am indebted to the people and communities of the Altiplano Occidental, especially those of Sipacapa and San Miguel Ixtahuacán, for their courtesy and trusting me with their experiences. In particular I should mention: Manuel Ambrocio; Francisco Bámaca; Margarita Bamaca; Crisanta Fernández; Rubén Feliciano; Andrés García (Alcaldía Indígena de Totonicapán); Padre Erik Gruloos; Ciriaco Juárez; Javier de León; Aníbal López; Aniceto López; Rolando López; Santiago López; Susana López; Gustavo Mérida; Isabel Mérida; Lázaro Pérez; Marcos Pérez; Antonio Tema; Delfino Tema; Juan Tema; Mario Tema; and Timoteo Velásquez. Also, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to the team of COPAE and the Pastoral Social of the Diocese of San Marcos for introducing me to the theme and their work. I especially thank: Marco Vinicio López; Roberto Marani; Udiel Miranda; Fausto Valiente; Sander Otten; Johanna van Strien; and Ruth Tánchez, for their help and friendship. I am also thankful to Msg. Álvaro Ramazzini. -

Digest #: Title

#9052 TTHHEE LLIIVVIINNGG SSAANNDDSS AMBROSE VIDEO PUBLISHING 2000 Grade Levels: 9-13+ 52 minutes DESCRIPTION Focuses on animal life in four extremely inhospitable deserts: the Namib's adaptive elephant, a dromedary roundup in Australia's outback, fish in thermal lakes in Mexico's Chihuahua desert, and the Sahara's Ennedi crocodiles. Survival is an eternal challenge to any life in these places. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: Science: Life Sciences • Standard: Understands relationships among organisms and their physical environment Benchmark: Knows how the interrelationships and interdependencies among organisms generate stable ecosystems that fluctuate around a state of rough equilibrium for hundreds or thousands of years (e.g., growth of a population is held in check by environmental factors such as depletion of food or nesting sites, increased loss due to larger numbers of predators or parasites) • Standard: Understands biological evolution and the diversity of life Benchmark: Understands the concept of natural selection (e.g., when an environment changes, some inherited characteristics become more or less advantageous or neutral, and chance alone can result in characteristics having no survival or reproductive value; this process results in organisms that are well suited for survival in particular environments) INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. To list physical features and capabilities of the desert elephant, gemsbok, warthog, ostrich, dromedary, pupfish, and crocodile. 2. To research how these animals survive in their environment. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Evolutionary Adaptations Desert Elephant of the Namib Desert (Namibia): • “Snowshoe feet” provide a soft wide track on sand. • It survives days without water while the elephants of the savanna of East Africa drink 40 to 50 gallons a day.