Development of Community Based Ecotourism in Abune Yosef Massif, Northern Ethiopia: Potential, Challenges and Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Ethnobotany, Diverse Food Uses, Claimed Health Benefits And

Shewayrga and Sopade Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2011, 7:19 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/7/1/19 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Ethnobotany, diverse food uses, claimed health benefits and implications on conservation of barley landraces in North Eastern Ethiopia highlands Hailemichael Shewayrga1* and Peter A Sopade2,3 Abstract Background: Barley is the number one food crop in the highland parts of North Eastern Ethiopia produced by subsistence farmers grown as landraces. Information on the ethnobotany, food utilization and maintenance of barley landraces is valuable to design and plan germplasm conservation strategies as well as to improve food utilization of barley. Methods: A study, involving field visits and household interviews, was conducted in three administrative zones. Eleven districts from the three zones, five kebeles in each district and five households from each kebele were visited to gather information on the ethnobotany, the utilization of barley and how barley end-uses influence the maintenance of landrace diversity. Results: According to farmers, barley is the “king of crops” and it is put for diverse uses with more than 20 types of barley dishes and beverages reportedly prepared in the study area. The products are prepared from either boiled/roasted whole grain, raw- and roasted-milled grain, or cracked grain as main, side, ceremonial, and recuperating dishes. The various barley traditional foods have perceived qualities and health benefits by the farmers. Fifteen diverse barley landraces were reported by farmers, and the ethnobotany of the landraces reflects key quantitative and qualitative traits. Some landraces that are preferred for their culinary qualities are being marginalized due to moisture shortage and soil degradation. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

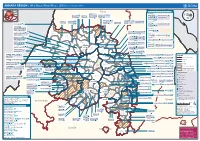

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Census Data/Projections, 1999 & 2000

Census data/Projections, 1999 & 2000 Jan - June and July - December Relief Bens., Supplementary Feeding Bens. TIGRAY Zone 1994 census 1999 beneficiaries - May '99 2000 beneficiaries - Jan 2000 July - Dec 2000 Bens Zone ID/prior Wereda Total Pop. 1999 Pop. 1999 Bens. 1999 bens % 2000 Pop. 2000 Bens 2000 bens Bens. Sup. July - Dec Bens July - Dec Bens ity Estimate of Pop. Estimate % of Pop. Feeding % of pop 1 ASEGEDE TSIMBELA 96,115 111,424 114,766 1 KAFTA HUMERA 48,690 56,445 58,138 1 LAELAY ADIYABO 79,832 92,547 5,590 6% 95,324 7,800 8% 11,300 12% Western 1 MEDEBAY ZANA 97,237 112,724 116,106 2,100 2% 4,180 4% 1 TAHTAY ADIYABO 80,934 93,825 6,420 7% 96,639 18,300 19% 24,047 25% 1 TAHTAY KORARO 83,492 96,790 99,694 2,800 3% 2,800 3% 1 TSEGEDE 59,846 69,378 71,459 1 TSILEMTI 97,630 113,180 37,990 34% 116,575 43,000 37% 15,050 46,074 40% 1 WELKAIT 90,186 104,550 107,687 Sub Total 733,962 850,863 50,000 6% 876,389 74,000 8% 15,050 88,401 10% *2 ABERGELE 58,373 67,670 11,480 17% 69,700 52,200 75% 18,270 67,430 97% *2 ADWA 109,203 126,596 9,940 8% 130,394 39,600 30% 13,860 58,600 45% 2 DEGUA TEMBEN 89,037 103,218 7,360 7% 106,315 34,000 32% 11,900 44,000 41% Central 2 ENTICHO 131,168 152,060 22,850 15% 156,621 82,300 53% 28,805 92,300 59% 2 KOLA TEMBEN 113,712 131,823 12,040 9% 135,778 62,700 46% 21,945 67,700 50% 2 LAELAY MAYCHEW 90,123 104,477 3,840 4% 107,612 19,600 18% 6,860 22,941 21% 2 MEREB LEHE 78,094 90,532 14,900 16% 93,248 57,500 62% 20,125 75,158 81% *2 NAEDER ADET 84,942 98,471 15,000 15% 101,425 40,800 40% 14,280 62,803 62% 2 -

F-3: Livelihood Improvement Component

F-3: Livelihood Improvement Component F-4: Activity Sheet of the Verification Project Appendix F: Verification Projects F-4: Activity Sheet of the Verification Projects Table of Contents Page Agricultral Promotion Component ....................................................................................................... F-4-1 Natural Resource Management Component ........................................................................................ F-4-23 Livelihood Improvement Component .................................................................................................. F-4-31 F-4-i Appendix F: Verification Projects F-4: Activity Sheet of the Verification Projects Activity Sheet for JALIMPS Verification Project Agricultural Promotion Component 1: 1. Activity Demonstration/Verification Plot: Primary Crops (15 activities in total) Name 2. Site Ebinate, Simada, Bugena, Gidan, Kobo, Mekedela, Legambo, Aregoba - 2009 meher season: Ebinate, Simada, Bugena, Gidan, Mekedela, Kobo - 2009/10 belg season: Gidan, Mekedela, Legambo - 2010 meher season: Ebinate, Simada, Bugena, Gidan, Kobo 3. Objectives Demonstration/verification of integrated approaches for the improvement of productivity of primary crops & farm land conservation in the watershed. 4. Implementer CRGs under the guidance & supervision of DAs & WAO 5. Beneficiaries CRGs: 34 CRGs formed 34 CRGs x 5 members = 170 members (beneficiaries) 6. Activity Establishment of demonstration/verification plot(s) for the integrated approaches Description for the productivity improvement -

Heading with Word in Woodblock

Amhara Region, Area brief Regional Overview The Amhara Region is located in the northwestern part of Ethiopia; its land area is estimated at about 170,000 square kilometers. Amhara borders Tigray Region in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumuz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan in the west. Based on the 2007 figures from the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia, Amhara has an estimated total population of 20,136,000. 88% of the population is estimated to be rural inhabitants, while 12% are urban dwellers. Bahir-Dar is the capital city of the Amhara Regional State. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 167 woredas (districts). There are about 3,429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units). Decision-making power has been decentralized to woredas and thus the woredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas. The historic Amhara region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1,500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, as well as millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. Located in this region are the world-renowned Blue Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder palace, and the Lalibela rock-hewn churches. The land in Amhara has been cultivated for millennia with no variations or improvement in the farming techniques. The resulting environmental damage has contributed to the trend of deteriorating climate with frequent droughts, loss of crops and the resulting food shortage. Of the 167 woredas in the region, fifty-eight (35%) are drought-prone and chronically food- insecure. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

Market Assessment Report – Ethiopia

Multi-Country Assessment of Employment and Entrepreneurship Opportunities for Youth in High Growth Potential Value Chains within the Agriculture Sector Ethiopia 2013 kjk Conducted in partnership with Dalberg Global Development Advisors Market Assessment Report – Ethiopia Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................4 Acronyms……………… ...........................................................................................................................5 List of Figures …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 List of Tables………… ...........................................................................................................................7 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................8 1. Background ........................................................................................................................... 13 1.1. Youth unemployment in Ethiopia.................................................................................................... 13 1.2. Why Agriculture? ............................................................................................................................. 14 1.3. Why this age group? ........................................................................................................................ 15 1.4. About this study .............................................................................................................................. -

FEWS NET/WFP Joint Trip Report

FEWS NET/WFP Joint Trip Report Activity Name: WFP- FEWS NET Joint mid-Belg season assessment Reported by: Zerihun Mekuria (FEWS NET) and Alemu Berhe (WFP) Dates of travel: 22 to 30 April, 2015 Area Visited: North Wollo, South Wollo and North Shewa zones of Amhara Region Reporting date: 02 May, 2015 Highlights of the findings: The onset of the February to May Belg 2015 has been delayed by more than six weeks in North and South Wollo zones and the rain started towards the end of March (20 – 25 March) except for the North Shewa zone where the current Belg started around mid-January and resumed in mid-March for about three to four days. The amount of the rainfall is ranges from low to heavy but distribution is uneven. In all Belg benefiting areas of northeastern Amhara, it has been unusually warmer and drier since mid-March. Except for the timely planting in mid-January in some areas in North Shewa zone, Belg planting as well delayed by about six to eight weeks in most highlands of northeastern Amhara. Delay on the onset of Belg rains and prolonged drier periods in the season has resulted in a much below average planting coverage where the current planting is about 42%, 51% and 26% of the normal area is planted in North Wollo, South Wollo and North Shewa zones respectively. Except for few crops planted in January in North Shewa zone which are currently at fruit setting stage, most of the crops planted are at early vegetative stage and some seeds remained aborted. -

Woreta-Woldiya Road Project

RP1 36 Volume 8 THE FEDERAL DEMUCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA Ethiopian Roads Authority Public Disclosure Authorized Preparation of Resettlement Action Plan for Woreta-WoWdiya road ..' Public Disclosure Authorized ~r $ L _ _ _ _ Public Disclosure Authorized *rt f '6b2i :f 4 8USv:2376?I 1. A hb Public Disclosure Authorized RAP; Woreta - Woldiya Final Report Table of Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................... 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................... 3 2. DESCRIPTIONS OF PROJECT ROAD . ....................................................11 2.1 Background ....................................................... 11 2.2 Socio-economic Benefit ...................................................... 12 3. LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT PROCEDURES ................... 12 3.1 Scope of Land Acquisition and Resettlement .................................................. 12 Properties to be affected ...................................................... 14 4. SOCIO ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS . ..................................................... 20 4.1 Demography ...................................................... 20 4.2 Human and Natural Resources of the Project Areas ........................ ................ 20 4.3 Economic Activity ...................................................... 21 4.4 Implications for the project ................. ...................................... 21 5. POLICY, LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK .. 22 5.1 Policy Framework ...................................................... -

World Bank Document

SFG3021 O Public Disclosure Authorized O Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Transmission Upgrading & Reinforcement Project Coordination Office, Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia August 2016 (Revised Report) Table of Contents List34T of Figures ..............................................................34T .......................................................................... 6 List34T of Abbreviations ..............................................................34T ............................................................... 6 Eexecutive34T Summary 34T ................................................................................................................................... 8 I.34T General Background and Introduction 34T ................................................................................................ 17 1.1.34T General Background34T ..................................................................................................................... 17 1.2.34T Introduction ..............................................................34T .................................................................... 18 1.3.34T Objectives of the RAP ..............................................................34T .................................................... 18 1.4.34T Scope of Work (SOW) ..............................................................34T ................................................... 19 1.5.34T Approach and Methodology