Ethnobotany, Diverse Food Uses, Claimed Health Benefits And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

The Case of Smallholder Farmers at Guba Lafto Woreda, Amhara National Region State, Ethiopia

VULNERABILITY AND ADAPTATION PRACTICES TO CLIMATE CHANGE: THE CASE OF SMALLHOLDER FARMERS AT GUBA LAFTO WOREDA, AMHARA NATIONAL REGION STATE, ETHIOPIA M.Sc. THESIS TSEGAYE TEMESGEN WONDO GENET COLLEGE OF FORESTRY AND NATURAL RESOURCES, HAWASSA UNIVERSITY, ETHIOPIA JUNE, 2018 VULNERABILITY AND ADAPTATION PRACTICES TO CLIMATE CHANGE: THE CASE OF SMALLHOLDER FARMERS AT GUBA LAFTO WOREDA, AMHARA NATIONAL REGION STATE, ETHIOPIA TSEGAYE TEMESGEN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE SMART AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE ASSESMENT, WONDO GENET COLLEGE OF FORESTRY AND NATURAL RESOURCES, SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES WONDO GENET COLLEGE OF FORESTRY AND NATURAL RESOURCES WONDO GENET, ETHIOPIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CLIMATE SMART AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE ASSESSMENT (SPECIALIZATION: CLIMATE SMART AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE ASSESMENT) JUNE, 2018 II Approval sheet1 This is to certify that the thesis entitled “vulnerability and adaptation practices to climate change: the case of smallholder farmers at Guba Lafto woreda, Amhara national region state, Ethiopia” is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Sciences with specialization in climate smart agricultural landscape assessment. It is a record of original research carried out by Tsegaye Temesgen Id. No Msc/CSAL/R0012/09, under my supervision; and no part of the thesis has been submitted for any other degree or diploma. The assistance and help received during the courses of this investigation have been duly acknowledged. -

Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho

Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2020; 9(4): 113-121 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/aff doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20200904.13 ISSN: 2328-563X (Print); ISSN: 2328-5648 (Online) Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho (Pennisetum pedicellatum ) Grass Under Irrigation, in Dehana District, Wag Hemra Zone, Ethiopia Awoke Kefyalew 1, Berhanu Alemu 2, Alemu Tsegaye 3 1Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Oda Bultum University, Chiro, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia 3Sekota Dry Land Agricultural Research Center, Sekota, Ethiopia Email address: To cite this article: Awoke Kefyalew, Berhanu Alemu, Alemu Tsegaye. Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho (Pennisetum pedicellatum ) Grass Under Irrigation, in Dehana District, Wag Hemra Zone, Ethiopia. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries . Vol. 9, No. 4, 2020, pp. 113-121. doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20200904.13 Received : June 5, 2020; Accepted : June 19, 2020; Published : July 28, 2020 Abstract: The experiment was conducted to evaluating the effects of fertilizer and harvesting age on agronomic performance, chemical composition and economic feasibility of Desho (Pennisetum Pedicellatum) grass under irrigation, in Ethiopia. A factorial arrangement with four fertilizer types (control, urea, compost and urea + compost), and three harvesting ages (90, 120 and 150) with three replications were used. Data on morphological characteristics of the grass were recorded. Based on the data collected, harvesting age was significantly affected the agronomic parameters of the grass. Plant height (PH), number of tillers per plant (NTPP), number of leaves per plant (NLPP), number of leaves per tiller (NLPT), dry matter yield (DMY), leaf length (LL) and leaf area (LA) were increased with increasing harvesting age, while leaf to stem ratio (LSR) showed a decreasing trend. -

Development of Community Based Ecotourism in Abune Yosef Massif, Northern Ethiopia: Potential, Challenges and Prospects

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT OF COMMUNITY BASED ECOTOURISM IN ABUNE YOSEF MASSIF, NORTHERN ETHIOPIA: POTENTIAL, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS A Final Draft Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts in Tourism Development and Management BY WUBSHET KASSA ADVISOR: FEYERA SENBETA (Ph.D) JUNE 2018 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT OF COMMUNITY BASED ECOTOURISM IN ABUNE YOSEF MASSIF, NORTHERN ETHIOPIA: POTENTIAL, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS BY WUBSHET KASSA Approval of Board of Examiners Name Signature Date Advisor _________________ _____________ ________________ Internal Examiner ______________ _____________ _________________ External Examiner ________________ _____________ _________________ ii DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this thesis entitled “Development of community based Ecotourism in Abune Yoseph massif, Northern Ethiopia: Potential, Challenges and Prospects” is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University, and all sources of material used for the thesis have been duly acknowledged. Name: Wubshet kassa Signature: _____________ Date : ______________ This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as University advisor. Name : Feyera Senbeta (PhD) Signature:________________________ Date : __________________________ iii Acknowledgement I would like to thank all my families, friends, collogues and lecturers who have helped and inspired me during my MA study. My first special gratitude goes to Dr. Feyera Senbeta, who was my thesis advisor and whose encouragement, guidance and support from the initial to the final stage enabled me to grasp some know-how on this particular theme. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

Economic Efficiency of Smallholder Farmers in Barley Production in Meket District, Ethiopia

Vol. 10(10), pp. 328-338, October 2018 DOI: 10.5897/JDAE2018.0960 Article Number: 12FCF3758529 ISSN: 2006-9774 Copyright ©2018 Journal of Development and Agricultural Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JDAE Economics Full Length Research Paper Economic efficiency of smallholder farmers in barley production in Meket district, Ethiopia Getachew Wollie1*, Lemma Zemedu2 and Bosena Tegegn2 1Department of Economics, College of Business and Economics, Samara University, Ethiopia. 2Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Haramaya University, Ethiopia. Received 10 May, 2018; Accepted 31 July, 2018 This study analyzed the economic efficiency of smallholder farmers in barley production in the case of Meket district, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. A cross sectional data collected from a sample of 123 barley producers during the 2015/2016 production season was used for the analysis. Two stages random sampling method was used to select sample respondents. The translog functional form was chosen to estimate both production and cost functions and OLS estimation method was applied to identify allocative and economic inefficiencies factors, while technical inefficiency factors were analyzed by using single stage estimation approach. The estimated stochastic production frontier model indicated input variables such as fertilizer, human labor and oxen power as significant variables that increase the quantity of barley output, while barley seed had a negative effect. The estimated mean levels of technical, allocative and economic efficiencies of the sample farmers were about 70.9, 68.6 and 48.8%, respectively which revealed the presence of a room to increase their technical, allocative and economic efficiencies level on average by 29.1, 31.4 and 51.2%, respectively with the existing resources. -

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook Update November 2011

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook Update November 2011 Good rains likely to stabilize food security in the south The October to December Deyr rains are performing well Figure 1. Most-likely food security outcomes (October in most parts of the southern and southeastern pastoral to December 2011) and agropastoral areas, easing the shortage of pastoral resources. This, coupled with ongoing humanitarian assistance, will continue to stabilize food security among poor and very poor households in these areas. Nonetheless, about 4 million people will continue to require humanitarian assistance through the end of 2011 across the country. Prices of staple foods have generally started declining following the fresh Meher harvest, although they remain higher than the five‐year average. This will continue to constrain access to food over the coming months among the rural and urban poor who heavily depend on purchase to fulfill their minimum food requirements. For more information on FEWS NET’s Food Insecurity Severity Scale, During the January to March 2012 period, Crisis level food please see: www.fews.net/FoodInsecurityScale insecurity will extend to the dominantly Belg producing Source: FEWS NET Ethiopia and WFP zones in the northeastern highlands as well as into some marginal Meher cropping areas due to the below normal Figure 2. Most‐likely food security outcomes (January to 2011 harvests. Similarly, as the long dry season March 2012) (December to March) progresses, deterioration in food security is likely in some southern pastoral and agropastoral woredas which were severely affected by the recent drought. Updated food security outlook through March 2012 Food security in most parts of the country has stabilized as a result of improved market supply and declining prices following the Meher harvest, ongoing humanitarian assistance, and the current good Deyr/Hageya rains in the southern and southeast pastoral and agropastoral. -

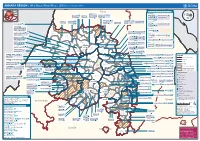

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

The Case of Dessie Zuria Woreda

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1700 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2855 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/JESD Vol.10, No.5, 2019 Determinants of Households Saving Capacity and Bank Account Holding Experience in Ethiopia: The Case of Dessie Zuria Woreda Bazezew Endalew College of Business and Economics, Department of Economics, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia Abstract This research has been an attempt to identify the major determinants that affect households saving capacity and their experience of adopting formal financial institutions (banks) in the case of Dessie Zuria Woreda. To do so, an individual base cross-sectional data analysis along with the two stage sampling technique of both purposive and random sampling technique was undertaken. To analyze the data, the study employed two sets of models (logistic and the method of principal component analysis). The econometric results of the study indicates that determinants like lack of credit access, lack of financial planning, complexity of banking system, monthly expenditure on stimulants, sex, significantly and negatively affects households saving capacity, but monthly income, age, bank account holding experience, marital status, and occupation positively and significantly affects saving capacity. In similar fashion, determinants include improper government policy, weak institutional set up, complexity of banking system, distance in Km away from their home to financial institutions, and religion significantly and negatively affect the probability of households to be banked, on the other hand, sex of households, credit access, income, marital status, education and age positively and significantly affects the probability of households to be banked. -

Census Data/Projections, 1999 & 2000

Census data/Projections, 1999 & 2000 Jan - June and July - December Relief Bens., Supplementary Feeding Bens. TIGRAY Zone 1994 census 1999 beneficiaries - May '99 2000 beneficiaries - Jan 2000 July - Dec 2000 Bens Zone ID/prior Wereda Total Pop. 1999 Pop. 1999 Bens. 1999 bens % 2000 Pop. 2000 Bens 2000 bens Bens. Sup. July - Dec Bens July - Dec Bens ity Estimate of Pop. Estimate % of Pop. Feeding % of pop 1 ASEGEDE TSIMBELA 96,115 111,424 114,766 1 KAFTA HUMERA 48,690 56,445 58,138 1 LAELAY ADIYABO 79,832 92,547 5,590 6% 95,324 7,800 8% 11,300 12% Western 1 MEDEBAY ZANA 97,237 112,724 116,106 2,100 2% 4,180 4% 1 TAHTAY ADIYABO 80,934 93,825 6,420 7% 96,639 18,300 19% 24,047 25% 1 TAHTAY KORARO 83,492 96,790 99,694 2,800 3% 2,800 3% 1 TSEGEDE 59,846 69,378 71,459 1 TSILEMTI 97,630 113,180 37,990 34% 116,575 43,000 37% 15,050 46,074 40% 1 WELKAIT 90,186 104,550 107,687 Sub Total 733,962 850,863 50,000 6% 876,389 74,000 8% 15,050 88,401 10% *2 ABERGELE 58,373 67,670 11,480 17% 69,700 52,200 75% 18,270 67,430 97% *2 ADWA 109,203 126,596 9,940 8% 130,394 39,600 30% 13,860 58,600 45% 2 DEGUA TEMBEN 89,037 103,218 7,360 7% 106,315 34,000 32% 11,900 44,000 41% Central 2 ENTICHO 131,168 152,060 22,850 15% 156,621 82,300 53% 28,805 92,300 59% 2 KOLA TEMBEN 113,712 131,823 12,040 9% 135,778 62,700 46% 21,945 67,700 50% 2 LAELAY MAYCHEW 90,123 104,477 3,840 4% 107,612 19,600 18% 6,860 22,941 21% 2 MEREB LEHE 78,094 90,532 14,900 16% 93,248 57,500 62% 20,125 75,158 81% *2 NAEDER ADET 84,942 98,471 15,000 15% 101,425 40,800 40% 14,280 62,803 62% 2