Zenshinkan-Student-Handbook.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Mind at 20 Years: a Personal Reflection GATE

March 2014 Vol.10 No. 1 in a one-room zendo in Jersey City. So I invited folks from a series of meditation sessions that Roshi had led at a church in Manhattan, as well as people I was seeing in my spiritual direction work who were interested in meditation. We called ourselves Greenwich Village Zen Community (GVZC) and Sensei Kennedy became our first teacher. We sat on chairs or, in some cases, on toss pillows that were strewn on the comfortable library sofa; there was no altar, no daisan, only two periods of sitting with kin-hin in between, along with some basic instruction. My major . enduring memory is that on most Tuesdays as we began Still sitting at 7 pm, the chapel organist would begin his weekly practice. The organ was on the other side of the library wall so our sitting space was usually filled with Bach & Co. Having come to Zen to “be in silence,” it drove me rather crazy. Still Mind at 20 Years: I didn’t have to worry too much, though, because after a few months the staff told us the library was no longer available. So we moved, literally down the street, to the A Personal Reflection (cont. on pg 2) by Sensei Janet Jiryu Abels Still Mind Zendo was founded on a selfish act. I needed a sangha to support my solo practice and, since none existed, I formed one. Now, 20 years later, how grateful I am that enough people wanted to come practice with each other back then, for this same sangha has proved to be the very rock of my continuing awakening. -

Primary Point, Vol 5 Num 3

I 'I Non Profit Org. �I 'I U.S. Postage /I J PAID 1 Address Correction Requested i Permit #278 ,:i Return Postage Guaranteed Providence, RI 'I Ii ARY OINT PUBLISHED BY THE KWAN UM ZENSCHOOL K.B.C. Hong Poep Won VOLUME FIVE, NUMBER THREE 528 POUND ROAD, CUMBERLAND, RI 02864 (401)658-1476 NOVEMBER 1988 PERCEIVE UNIVERSAL SOUND An Interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn. we are centered we can control our This interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn strongly and thus our condition and situation. appeared in "The American Theosophist" feelings, (AT) in May 1985. It is reprinted by permis AT: When you refer to a "center" do you sion of the Theosophical Society in America, mean any particular point in the body? Wheaton, Illinois. The interviewer is Gary DSSN: No, it is not just one point. To be Doore. Zen Master Sahn is now ,I Seung strongly centered is to be at one with the to his students as Dae Soen Sa referred by universal center, which means infinite time Nim. (See note on 3) page and infinite space. Doore: What is Zen Gary chanting? The first time one tries chanting medita Seung Sahn (Dae Soen Sa Nim): Chanting is tion there will be much confused thinking, very important in our practice. We call it many likes, dislikes and so on. This indicates "chanting meditation." Meditation means keep that the whole mind is outwardly-oriented. ing a not-moving mind. The important thing in Therefore, it is necessary first to return to chanting meditation is to perceive the sound of one's energy source, to return to a single point. -

Omori Sogen the Art of a Zen Master

Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Omori Roshi and the ogane (large temple bell) at Daihonzan Chozen-ji, Honolulu, 1982. Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Hosokawa Dogen First published in 1999 by Kegan Paul International This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © The Institute of Zen Studies 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0–7103–0588–5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978–0–7103–0588–6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. Dedicated to my parents Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I - The Life of Omori Sogen Chapter 1 Shugyo: 1904–1934 Chapter 2 Renma: 1934–1945 Chapter 3 Gogo no Shugyo: 1945–1994 Part II - The Three Ways Chapter 4 Zen and Budo Chapter 5 Practical Zen Chapter 6 Teisho: The World of the Absolute Present Chapter 7 Zen and the Fine Arts Appendices Books by Omori Sogen Endnotes Index Acknowledgments Many people helped me to write this book, and I would like to thank them all. -

One Circle Hold Harmless Agreement

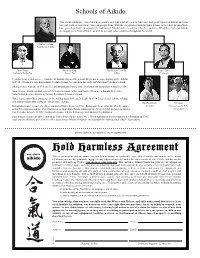

Schools of Aikido This is not a definitive list of Aikido schools/sensei, but a list of teachers who have had great impact on Aikido and who you will want to read about. You can google them. With the exception of Koichi Tohei Sensei, all teachers pictured here have passed on, but their school/style/tradition of Aikido has been continued by their students. All of these styles of Aikido are taught in the United States, as well as in many other countries throughout the world. Morihei Ueshiba Founder of Aikido Gozo Shioda Morihiro Saito Kisshomaru Ueshiba Koichi Tohei Yoshinkai/Yoshinkan Iwama Ryu Aikikai Ki Society Ueshiba Sensei (Ô-Sensei) … Founder of Aikido. Opened the school which has become known as the Aikikai in 1932. Ô-Sensei’s son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei, became kancho of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Shioda Sensei was one of Ô-Sensei’s earliest students. Founded the Yoshinkai (or Yoshinkan) school in 1954. Saito Sensei was Head Instructor of Ô-Sensei’s school in the rural town of Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture. Saito Sensei became kancho of Iwama Ryu upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Tohei Sensei was Chief Instructor of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. In 1974 Tohei Sensei left the Aikikai Shin-Shin Toitsu “Ki Society” and founded or Aikido. Rod Kobayashi Bill Sosa Kobayashi Sensei became the direct student of Tohei Sensei in 1961. Kobayashi Sensei was the Chief Lecturer Seidokan International Aikido of Ki Development and the Chief Instructor of Shin-Shin Toitsu Aikido for the Western USA Ki Society (under Association Koichi Tohei Sensei). -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

WW July August.Pub

Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. —Gate of Sweet Nectar Zen Center of Los Angeles JULY / AUGUST 2011 Great Dragon Mountain / Buddha Essence Temple 2553 Buddhist Era Vol. 12 No. 4 Abiding Nowhere By Sensei Merle Kodo Boyd Book of Serenity, Case 75 Zuigan’s Permanent Principle Preface Even though you try to call it thus, it quickly changes. At the place where knowledge fails to reach, it should not be talked about. Here: is there something to penetrate? Main Case Attention! Zuigan asked Ganto, “What is the fundamental constant “Before we can say anything true about principle?” ourselves, we have changed. “ Ganto replied, “Moving.” Zuigan asked, “When moving, what then?” Ganto said, “You don’t see the fundamental constant The preface of this koan is clear. With wisdom and principle.” compassion, it points us in the direction of things as they Zuigan stood there thinking. are. Even as we perceive a thing, it changes. As we create Ganto remarked, “If you agree, you are not free of sense a name for what is, it is changing. As we use one word, and matter; if you don’t agree, you’ll be forever sunk in another is needed. This preface describes our human con- birth and death.” dition. An effort to settle in certainty will meet frustration and disappointment. Before we can say anything true Appreciatory Verse about ourselves, we have changed. What we say is only The round pearl has no hollows, partially true at best. The great raw gem isn’t polished. -

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

Women Living Zen: Japanese Soto Buddhist Nuns

Women Living Zen This page intentionally left blank Women Living Zen JAPANESE SOTO BUDDHIST NUNS Paula Kane Robinson Arai New York Oxford Oxford University Press 1999 Oxford University Press Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1999 by Paula Kane Robinson Arai Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arai, Paula Kane Robinson. Women living Zen : Japanese Soto Buddhist nuns Paula Kane Robinson Arai. p. em. ISBN 0-19-512393-X 1. Monastic and religious life for women—Japan. 2. Monastic and religious life (Zen Buddhism) —Japan. 3. Religious life —Sotoshu. 4. Buddhist nuns—Japan. I. Title, BQ9444.2.A73 1998 294.3'657-dc21 98-17675 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For mv parents, Masuko Arai Robinson Lucian Ford Robinson and my bodhisattva, Kito Shunko This page intentionally left blank FOREWORD Reflections on Women Encountering Buddhism across Cultures and Time Abbess Aoyama Shundo Aichi Zen Monastery for Women in Nagoya, Japan "We must all, male and female alike, profoundly respect Buddhist teachings and practice. -

Aikido Framingham Aikikai, Inc

Aikido Framingham Aikikai, Inc. 61 Fountain Street Framingham, MA 01701 (508) 626-3660 www.aikidoframingham.com Framingham Aikikai Information on Aikido Practice and Etiquette Welcome to Framingham Aikikai History Instructors and Certification Consistency of Technique Testing & Promotions Attendance Status & Fees Dojo Cleanliness Personal Cleanliness Logistical Information Etiquette Important Points About Aikido Practice (on the mat) Things to Keep in Mind As You Begin Aikido Practice Basic Concepts Iaido Japanese Terms Used in Aikido: USAF Test Requirements 1 Welcome to Framingham Aikikai! This document is intended to provide background and basic information and to address questions a new student of Aikido may to have. Aikido practice is fascinating but challenging. As a beginner, your main objective should be to get yourself onto the mat with some regularity. Beyond that, just relax, enjoy practicing and learning, and let Aikido unfold at its own pace. The instructors and your fellow students are resources that will provide you with continuing support. Don’t hesitate to ask questions or let them know if you need help or information. Feel free at any time to talk to the Chief Instructor at the dojo, on the phone or via email at [email protected]. History, Lineage & Affiliations Framingham Aikikai (FA) was founded in January 2000 by David Halprin, who studied for over twentyfive years as a student of Kanai Sensei at New England Aikikai in Cambridge. FA is a member dojo of the United States Aikido Federation (USAF). The USAF was founded in the 1960's by Yoshimitsu Yamada, 8th Dan, of New York Aikikai, and Mitsunari Kanai, 8th Dan, of New England Aikikai. -

Prajñatara: Bodhidharma's Master

Summer 2008 Volume 16, Number 2 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Women Acquiring the Essence Buddhist Women Ancestors: Hymn to the Perfection of Wisdom Female Founders of Tibetan Buddhist Practices Invocation to the Great Wise Women The Wonderful Benefits of a H. H. the 14th Dalai Lama and Speakers at the First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha Female Lineage Invocation WOMEN ACQUIRING THE ESSENCE An Ordinary and Sincere Amitbha Reciter: Ms. Jin-Mei Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao Chen-Lai On July 10, 1998, I invited the women of our Sangha to gather to explore the practice and lineage of women. Prajñatara: Bodhidharma’s Here are a few thoughts that helped get us started. Master Several years ago while I was visiting ZCLA [Zen Center of Los Angeles], Nyogen Sensei asked In Memory of Bhiksuni Tian Yi (1924-1980) of Taiwan me to give a talk about my experiences as a woman in practice. I had never talked about this before. During the talk, a young woman in the zendo began to cry. Every now and then I would glance her One Worldwide Nettwork: way and wonder what was happening: Had she lost a child? Ended a relationship? She cried and A Report cried. I wondered what was triggering these unstoppable tears? The following day Nyogen Sensei mentioned to me that she was still crying, and he had gently Newsline asked her if she could tell him why. “It just had not occurred to me,” she said, “that a woman could be a Buddha.” A few years later when I met her again, the emotions of that moment suddenly surfaced. -

Aikido and Spirituality: Japanese Religious Influences in a Martial Art

Durham E-Theses Aikid©oand spirituality: Japanese religious inuences in a martial art Greenhalgh, Margaret How to cite: Greenhalgh, Margaret (2003) Aikid©oand spirituality: Japanese religious inuences in a martial art, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk AIK3DO AND SPIRITUALITY: JAPANESE RELIGIOUS INFLUENCES IN A MARTIAL _ ART A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Department of East Asian Studies University of Durham Margaret Greenhalgh December 2003 AUG 2004 COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it may be published without her prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Zen and the Ways

...a book of profound importance.” — THE EASTERN BUDDHIST BOO*'1 ZENr and e warn TREVOR U LEGGETT Expression of Zen inspiration in everyday activities such as writing or serving tea. and in knightly arts such as fencing, came to be highly regarded in Japanese tradition. In the end. some of them were practiced as spiritual training in themselves; they were then called “Ways.” This book includes translations of some rare texts on Zen and the Ways. One is a sixteenth- century Zen text compiled from Kamakura temple records of the previous three centuries, giving accounts of the very first Zen interviews in Japan. It gives the actual koan “test questions” which disciples had to answer. In the koan called “Sermon,” for instance, among the tests are: How would you give a sermon to a one-month-old child? To someone screaming with pain in hell? To a foreign pirate who cannot speak your language? To Maitreya in the Tushita heaven? Extracts are translated from the “secret scrolls” of fencing, archery, judo, and so on. These scrolls were given in feudal days to pupils when they graduated from the academy, and some of them contain profound psychological and spiritual hints, but in deliberately cryptic form. They cannot be understood without long experience as a student of a Way, and the author drav years’ experience as a student teacher of the Way called jud( The text is accompanied b; drawings and plates. Zen and the Ways * # # # # # # # # #/) /fora 1778 <8> PHILLIPS ACADEMY # » «• OLIVER WENDELL-HOLMES $ I LIBRARY I CgJ rg) ^jper- amphora ; a£ altiora .