WW July August.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Mind at 20 Years: a Personal Reflection GATE

March 2014 Vol.10 No. 1 in a one-room zendo in Jersey City. So I invited folks from a series of meditation sessions that Roshi had led at a church in Manhattan, as well as people I was seeing in my spiritual direction work who were interested in meditation. We called ourselves Greenwich Village Zen Community (GVZC) and Sensei Kennedy became our first teacher. We sat on chairs or, in some cases, on toss pillows that were strewn on the comfortable library sofa; there was no altar, no daisan, only two periods of sitting with kin-hin in between, along with some basic instruction. My major . enduring memory is that on most Tuesdays as we began Still sitting at 7 pm, the chapel organist would begin his weekly practice. The organ was on the other side of the library wall so our sitting space was usually filled with Bach & Co. Having come to Zen to “be in silence,” it drove me rather crazy. Still Mind at 20 Years: I didn’t have to worry too much, though, because after a few months the staff told us the library was no longer available. So we moved, literally down the street, to the A Personal Reflection (cont. on pg 2) by Sensei Janet Jiryu Abels Still Mind Zendo was founded on a selfish act. I needed a sangha to support my solo practice and, since none existed, I formed one. Now, 20 years later, how grateful I am that enough people wanted to come practice with each other back then, for this same sangha has proved to be the very rock of my continuing awakening. -

Primary Point, Vol 5 Num 3

I 'I Non Profit Org. �I 'I U.S. Postage /I J PAID 1 Address Correction Requested i Permit #278 ,:i Return Postage Guaranteed Providence, RI 'I Ii ARY OINT PUBLISHED BY THE KWAN UM ZENSCHOOL K.B.C. Hong Poep Won VOLUME FIVE, NUMBER THREE 528 POUND ROAD, CUMBERLAND, RI 02864 (401)658-1476 NOVEMBER 1988 PERCEIVE UNIVERSAL SOUND An Interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn. we are centered we can control our This interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn strongly and thus our condition and situation. appeared in "The American Theosophist" feelings, (AT) in May 1985. It is reprinted by permis AT: When you refer to a "center" do you sion of the Theosophical Society in America, mean any particular point in the body? Wheaton, Illinois. The interviewer is Gary DSSN: No, it is not just one point. To be Doore. Zen Master Sahn is now ,I Seung strongly centered is to be at one with the to his students as Dae Soen Sa referred by universal center, which means infinite time Nim. (See note on 3) page and infinite space. Doore: What is Zen Gary chanting? The first time one tries chanting medita Seung Sahn (Dae Soen Sa Nim): Chanting is tion there will be much confused thinking, very important in our practice. We call it many likes, dislikes and so on. This indicates "chanting meditation." Meditation means keep that the whole mind is outwardly-oriented. ing a not-moving mind. The important thing in Therefore, it is necessary first to return to chanting meditation is to perceive the sound of one's energy source, to return to a single point. -

Omori Sogen the Art of a Zen Master

Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Omori Roshi and the ogane (large temple bell) at Daihonzan Chozen-ji, Honolulu, 1982. Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Hosokawa Dogen First published in 1999 by Kegan Paul International This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © The Institute of Zen Studies 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0–7103–0588–5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978–0–7103–0588–6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. Dedicated to my parents Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I - The Life of Omori Sogen Chapter 1 Shugyo: 1904–1934 Chapter 2 Renma: 1934–1945 Chapter 3 Gogo no Shugyo: 1945–1994 Part II - The Three Ways Chapter 4 Zen and Budo Chapter 5 Practical Zen Chapter 6 Teisho: The World of the Absolute Present Chapter 7 Zen and the Fine Arts Appendices Books by Omori Sogen Endnotes Index Acknowledgments Many people helped me to write this book, and I would like to thank them all. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

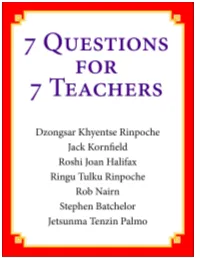

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

Zenshinkan-Student-Handbook.Pdf

Zenshinkan Center for Japanese Martial, Spiritual,and Cultural Arts Student Handbook ZENSHINKAN DOJO STUDENT HANDBOOK CONTENTS The Way of Transformation .............................................................................................................. 2 Welcome to Zenshinkan Dojo ........................................................................................................... 3 Rules During Practice, Composed by the Founder ........................................................................... 5 Shugyo Policy .................................................................................................................................... 6 Basic Dojo Etiquette .......................................................................................................................... 7 Helpful Words and Phrases .............................................................................................................. 12 A History of Aikido ............................................................................................................................ 15 Zen Training ...................................................................................................................................... 17 For more information On: Our Lineage Test Requirements, Information and Applications Programs, Class Schedules and Upcoming Events Weapons Forms Techniques Zen Training Our website is a rich resource for our dojo’s current activities as well as our history. We also welcome and encourage your -

Prajñatara: Bodhidharma's Master

Summer 2008 Volume 16, Number 2 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Women Acquiring the Essence Buddhist Women Ancestors: Hymn to the Perfection of Wisdom Female Founders of Tibetan Buddhist Practices Invocation to the Great Wise Women The Wonderful Benefits of a H. H. the 14th Dalai Lama and Speakers at the First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha Female Lineage Invocation WOMEN ACQUIRING THE ESSENCE An Ordinary and Sincere Amitbha Reciter: Ms. Jin-Mei Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao Chen-Lai On July 10, 1998, I invited the women of our Sangha to gather to explore the practice and lineage of women. Prajñatara: Bodhidharma’s Here are a few thoughts that helped get us started. Master Several years ago while I was visiting ZCLA [Zen Center of Los Angeles], Nyogen Sensei asked In Memory of Bhiksuni Tian Yi (1924-1980) of Taiwan me to give a talk about my experiences as a woman in practice. I had never talked about this before. During the talk, a young woman in the zendo began to cry. Every now and then I would glance her One Worldwide Nettwork: way and wonder what was happening: Had she lost a child? Ended a relationship? She cried and A Report cried. I wondered what was triggering these unstoppable tears? The following day Nyogen Sensei mentioned to me that she was still crying, and he had gently Newsline asked her if she could tell him why. “It just had not occurred to me,” she said, “that a woman could be a Buddha.” A few years later when I met her again, the emotions of that moment suddenly surfaced. -

Teaching Letters of Zen Master Seung Sahn • Page 1195 © 2008 Kwan Um School of Zen •

601 13 June, 1977 Dear Soen Sa Nim, Lincoln Rhodes sent me the color photo of the four of us before the altar of your center in Los Angeles. It brought back very pleasant memories of your hospitality and our happy time together. I will take the photo with me to Japan on a forthcoming trip as something very interesting to show to my teacher Yamada Koun Roshi and to Dharma friends. Our training schedule is well under way, and a five-day seshin is scheduled to begin the end of this week. I find that new students in their 30’s and 40’s are appearing more and more. May you continue to enjoy good health! Robert Aitken July 8, 1977 Dear Aitken Roshi, Thank you for your postcard. I am happy to hear you are busy and attracting older students. I will be traveling in Korea and Japan, and if my schedule permits, I will try to visit your teacher. I will be traveling with ten American students, so it may be difficult to rearrange our travel arrangements, but perhaps on my return trip, I can stop in Hawaii. Sometime, I would like to visit your Zen Center. Yours in the Dharma, S.S. Teaching Letters of Zen Master Seung Sahn • Page 1195 © 2008 Kwan Um School of Zen • www.kwanumzen.org 602 July 3, 1977 Dear Soen Sa Nim, How was your “vacation” out on the West coast? Sherry has just finished talking to the Providence Center and she tells me that your health is not good. -

Water Wheel Being One with All Buddhas, I Turn the Water Wheel of Compassion

Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. —Gate of Sweet Nectar Zen Center of Los Angeles MARCH / APRIL 2011 Great Dragon Mountain / Buddha Essence Temple 2553 Buddhist Era Vol. 12 No. 2 Continuous Practice/ Ceaseless Practice By Sensei Merle Kodo Boyd “On the great road of Buddha Ancestors there is always unsurpassable practice, continuous and sustained. It forms the circle of the way and is never cut off. Between aspiration, practice, enlightenment, and nirvana, there is not a moment’s gap; continuous practice is the circle of the way….” Continuous or ceaseless practice is always occurring and is always now. When we look for its source or its effort, its accomplishment or its achievement, we cannot locate them. Still, it continues without interruption. For all of us, there was a day when we first sat zazen, but that Jizo Bodhisattva, protector of wayfarers and travelers, was not the day on which our practice began. Instead, it manifests ceaseless practice through his Great Vow. seems that we sat down on the cushion in response to all of the life that preceded that day. Our continuous practice is the natural expression and the natural everything that enters. We may not succeed, but we are fulfillment of our life. capable of this. Such a vast and inclusive mind is already and continuously ours, and yet we must exert some kind An aspect of that practice requires effort, resolve, of effort in order to experience it. We must make an and action, and an aspect of that practice does not effort to sustain it. -

2018 WW Oct-Dec

Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. — Gate of Sweet Nectar 2019 Winds of Change by Wendy Egyoku Nakao We turn the calendar page and enter the year 2019. This is a time to pause and refresh, breath- ing in and breathing out breaths of renewal. When you turn the calendar page with intention, it is like revolving a sutra—allowing the old pages to breathe, circulat- ing love and wisdom everywhere. What are your vows—your deepest heart’s desire—for yourself in the new year? What is your heart’s desire for your loved ones, for your fellow beings with which you share this earth, and for the earth and universe itself? This past fall, intense fi re storms raged throughout California leaving death and destruction in their wake. In the midst of this, Roshi Bernie, ZCLA’s second abbot and Program cover for Abbot Installation, 1999. my beloved Dharma teacher, passed away in Montague, MA. In Zen speak, we say that “He went to another realm to teach,” but I hope he is resting, having a cigar, and Mountain in the years to come and that the sangha, and taking a hot bath somewhere. As if these unsettling move- all who take the seats that guide it, will remain true to its ments weren’t enough, I announced that I am descending purpose, lead from a heart of love and wisdom, and not the mountain after twenty years as Abbot and that Sensei regress in fulfi lling their vows. Faith-Mind will ascend the mountain in 2019. -

Water Wheel Being One with All Buddhas, I Turn the Water Wheel of Compassion

Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. —Gate of Sweet Nectar Zen Center of Los Angeles / Buddha Essence Temple Vol. 10 No. 4 2551 Buddhist Era JULY/AUGUST 2009 No Such Thing By Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao In his The Second Book of the Tao, author and translator Stephen Mitchell relays this account: Great Dragon Mountain founder As he was eating by the side of the road, Lieh-tzu saw an Maezumi Roshi old skull. He pulled it out of the weeds, contemplated it, and would often speak said, “Only you and I know that there is no such thing as of birth-and-death death and no such thing as life.” from three perspec- tives: 1) of being Mitchell’s commentary: born and dying, 2) of spiritual awaken- The philosopher Lieh-tzu has stopped for lunch on his ing, and 3) of the Garden Kanzeon’s “no fear” mudra. journey from here to there. He sits down by the side of the birth-and-death of road, opens his knapsack, takes out a few rice balls and a each moment. Each piece of dried fish. It’s a leisurely meal. He has nowhere in nen, a now-mind moment, brings into stark relief the real- particular to go. ity that is our life. You may tell yourself that you are living such-and-such a life, but can you see that you are being Suddenly he notices an old skull. He pulls it out of the lived—that this reality is you yourself? Birth and death are weeds for a tête-à-tête. -

Kata: the Heart of Egami Karate-Do Bodhidharma Is a Buddhist Monk Of

Kata: The Heart of Egami Karate-Do Bodhidharma is a Buddhist monk of the 5th century who introduced Zen Buddhism to China and is universally recognized as the founder of Eastern martial arts. He indicated to his followers, as a way to achieve the purification and pacification of the soul, also physical activity, being soul and body inseparable. Physical training consisted of learning combat techniques: 18 hand self-defense techniques. If Zazen meditation is a cure for the soul and mind, then body training is Dōzen (moving meditation). It is an apparently difficult method to explain, by a Buddhist monk, from whom we would have expected attention concentrated on the care of the spirit and the renunciation of any worldly desire, for the achievement of peace and happiness. Indeed, Bodhidharma could never have taught his disciples a mere art of war: we must therefore deduce that the study of combat techniques had a deeper meaning for him, the result of reflection, or an intuition on the limits that human beings often do not know and therefore cannot overcome. Perhaps, through this method, Bodhidharma intended to answer questions such as: Is it possible to manage the natural aggressiveness of the human being? Where does it come from? How can we govern and appease states of mind such as anger, resentment, hatred, fear? How can we sublimate these hostile feelings by transforming them into compassion and love? The anger, hatred and fear directed towards others immediately return against those who experience them: this becomes evident through the training of fighting techniques. Perhaps it is precisely to answer these questions that he decided to teach his followers fighting techniques that could expose the true nature of the human being and overcome internal conflicts to obtain true harmony and therefore experience peace of mind; at the same time this method instilled fear and repugnance in the face of the idea of being able to cause suffering or even death to others.