Soldiers (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Identity and the British Common Soldier Steven Schwamenfeld

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 "The Foundation of British Strength": National Identity and the British Common Soldier Steven Schwamenfeld Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE ARTS AND SCIENCES “The Foundation of British Strength:” National Identity and the British Common Soldier By Steven Schwamenfeld A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Steven Schwamenfeld defended on Dec. 5, 2006. ___________________ Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Dissertation _____________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _________________ Michael Cresswell Committee Member ________________ Edward Wynot Committee Member Approved: ___________________ Neil Jumonville, Chair History Department The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables iv Abstract v Introduction 1 I. “Thou likes the Smell of Poother” 13 II. “Our Poor Fellows” 42 III. “Hardened to my Lot” 63 IV. “…to Conciliate the Inhabitants” 92 V. Redcoats and Hessians 112 VI. The Jewel in the Crown of Thorns 135 VII. Soldiers, Settlers, Slaves and Savages 156 VIII. Conclusion 185 Appendix 193 Bibliography 199 Biographical Sketch 209 iii LIST OF -

Exposition « 10 Ans De Parrainage Des Fusiliers Marins De Lorient »

Communiqué de presse - Invitation presse - Exposition en plein-air - Exposition « 10 ans de parrainage des Fusiliers marins de Lorient » Présentée du 4 juin au 30 septembre 2018 Le long des plages de Ouistreham Riva-Bella et de Colleville-Montgomery Cérémonie des Fusiliers marins de Lorient à Ouistreham Riva-Bella en 2017 © Ville de Ouistreham Riva-Bella - L. Rodriguez 28 845 soldats alliés débarquèrent le Jour-J à Sword Beach, entre Ouistreham Riva-Bella et Langrune. Le n°4 Commando, sous les ordres du Colonel Dawson, comptait six troupes anglaises et deux troupes menées par le Commandant Philippe Kieffer : les 177 Bérets verts français formant le 1er bataillon de fusiliers marins. L’exposition « 10 ans de parrainage des Fusiliers marins de Lorient » sera présentée pendant toute la saison estivale, du 4 juin au 30 septembre 2018, le long des plages de Ouistreham Riva-Bella et de Colleville-Montgomery. Elle retracera les 10 années passées depuis la date de signature de la charte de parrainage entre Ouistreham Riva-Bella et l’école des Fusiliers Marins de Lorient. L’historique Le 6 juin 2008, une charte de parrainage a été signée entre la Ville de Ouistreham Riva-Bella et l’école des Fusiliers Marins de Lorient afin de consolider le lien historique existant entre cette commune et cette école mais également pour renforcer le lien armée-nation. Forte de ce lien, l’école des Fusiliers marins de Lorient organisait, chaque année, une cérémonie de tradition sur la plage de Ouistreham Riva-Bella. Romain Bail, Maire de Ouistreham Riva-Bella, avait souhaité que ce partenariat s’étende vers la commune de Colleville-Montgomery pour des raisons historiques. -

E57jm-Cols Bleus.Pdf

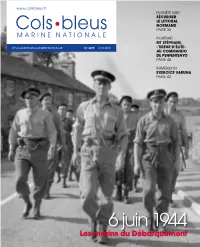

www.colsbleus.fr PLANÈTE MER SÉCURISER LE LITTORAL NORMAND PAGE 30 PORTRAIT MT STÉPHANE, LE MAGAZINE DE LA MARINE NATIONALE N° 3079 — JUIN 2019 « TIREUR D’ÉLITE » AU COMMANDO DE PENFENTENYO PAGE 40 IMMERSION EXERCICE VARUNA PAGE 42 6 juin 1944 Les marins du Débarquement Publicité Éditorial Des pionniers aux héritiers a mort au combat, très récente, Léon Gautier (96 ans) et Jean Morel (96 ans). de deux de nos frères Vous retrouverez leurs témoignages dans le « Passion d’armes, les premiers maîtres Marine » de ce mois-ci. Ce qu’ils nous enseignent, Cédric de Pierrepont et Alain l’héritage qu’ils nous lèguent, nous le portons Bertoncello, est un rappel éloquent tous, nous, marins, dans notre ADN. de l’engagement et du don de soi Soixante-quinze ans après cette date du « D-Day », auxquels nous devons tous être prêts. la Marine nationale porte encore haut aujourd’hui Ce don de soi, cet engagement pour les valeurs que ces « Français du Jour J » © F. LUCAS/MN© F. la Patrie jusqu’au sacrifice suprême, les marins ont su incarner : issus de milieux et d’origines Contre-Amiral Christophe Lucas, Lde 1944 y étaient prêts. C’était le cas, bien sûr, pour variées, d’âges différents, ils ont su s’unir malgré commandant les hommes du 1er Bataillon de Fusiliers Marins toutes leurs différences, pour défendre une seule de la Force maritime er des fusiliers marins Commandos (1 BFMC), qui, sous les ordres du et même cause : la libération de la France. et commandos capitaine de corvette Philippe Kieffer, débarquèrent Ainsi, cette devise des commandos britanniques, et commandant de la Marine, à Lorient. -

Philippe Kieffer Est Né Le 24 Octobre 1899 À Port-Au-Prince

COMMANDO KIEFFER Philippe Kieffer est né le 24 octobre 1899 à Port-au-Prince. Sa famille est originaire d'Alsace et c'est à la suite de l'annexion de l'Alsace- Moselle en 1870 qu'elle s'installe en Haïti. Il se porte volontaire après la déclaration de la guerre et entre dans la Marine le 10 septembre 1939. Il participe à la bataille de Dunkerque sur le cuirassé Courbet. Philippe Kieffer entend l'appel du général de Gaulle le 18 juin 1940 : dès le lendemain, l'enseigne de vaisseau part pour Londres. Il est l'un des premiers volontaires à rejoindre les Forces navales françaises libres. Philippe Kieffer se voit confier 16 volontaires en avril 1942, qui s'entraînent alors au camp de Camberley en Grande-Bretagne en compagnie du lieutenant Jean Pinelli. Début mai 1942, la petite troupe (23 hommes) est brevetée au camp d'Achnacarry (Ecosse) et reçoit officiellement le titre de "1ère Compagnie, Fusilier Marin Commando". Alors que ces hommes s'entraînent au dépôt d'Eastney, ils sont renforcés un peu plus tard par le Lieutenant Charles Trepel, nommé commandant en second du Commandant Kieffer. L'entraînement de commando est extrêmement difficile, les épreuves sont sélectives : les hommes doivent manœuvrer par tous les temps, sur tous les types d'obstacles : marches, entraînements à balles réelles, close- combat, etc. Le 14 juillet 1942, la petite compagnie composée d'une trentaine d'unités défile dans les rues de Londres à l'occasion de la fête nationale française. Le 10 août, la 1ère Compagnie est rattachée au n°10 Commando Inter Allied, basée au pays de Galles, dans laquelle des troupes de toutes les nations (Belgique, Hollande, Norvège, Pologne, Tchécoslovaquie, mais aussi des anti-nazis d'Allemagne et d'Autriche). -

D-Day Museum

ENGLISH D-DAY MUSEUM Normandie - France World War II As soon as he become German Chancellor in 1933, Hitler set about imposing a totalitarian dictatorship in Germany. He lost no time in remilitarizing the Rhineland and then proceeded to enter an alliance with Japan and Fascist Italy. By 1938, his ambition to invade the rest of Europe had become clear for all to see, with the annexation of Austria, followed by Czechoslovakia, Sudetenland, Bohemia and Moravia. France and Great Britain declared war on Germany on September 3rd 1939, two days after Hitler’s troops had inva- ded Poland. However, the relentless advance of the German forces, which swept through the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg in May 1940, proved to be unstoppable, and French and British troops were forced to flee to En- gland via Dunkirk. Paris fell on June 14th 1940 and Reynaud’s government resigned, leaving Marshal Pétain to sign the armistice and impose the Vichy regime. It was on June 18th that General de Gaulle, speaking from London, called on the French to resist. Light soon ap- peared at the end of the tunnel, however, for in the spring of 1942, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin started having regular meetings to plan a common strategy, while Allied forces won resounding victories in the Pacific, North Africa and, of course, at Stalingrad. An Eastern front finally became established, and in January 1943, the decision was taken in Casablanca to open up a new front in Western Europe. Troops would be landed on Normandy’s beaches. Preparations for Operation Overlord were underway. -

The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815

Men-at-Arms The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815 1FUFS)PGTDISÕFSr*MMVTUSBUFECZ(FSSZ&NCMFUPO © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Men-at-Arms . 496 The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815 Peter Hofschröer . Illustrated by Gerry Embleton Series editor Martin Windrow © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com THE PRUSSIAN ARMY OF THE LOWER RHINE 1815 INTRODUCTION n the aftermath of Napoleon’s first abdication in April 1814, the European nations that sent delegations to the Congress of Vienna in INovember were exhausted after a generation of almost incessant warfare, but still determined to pursue their own interests. The unity they had achieved to depose their common enemy now threatened to dissolve amid old rivalries as they argued stubbornly over the division of the territorial spoils of victory. Britain, the paymaster of so many alliances against France, saw to it that the Low Countries were united, albeit uncomfortably (and fairly briefly), into a single Kingdom of the Netherlands, but otherwise remained largely aloof from this bickering. Having defeated its main rival for a colonial empire, it could now rule A suitably classical portrait the waves unhindered; its only interest in mainland Europe was to ensure drawing of Napoleon’s nemesis: a stable balance of power, and peace in the markets that it supplied with General Field Marshal Gebhard, Prince Blücher von Wahlstatt both the fruits of global trading and its manufactured goods. (1742–1819), the nominal C-in-C At Vienna a new fault-line opened up between other former allies. of the Army of the Lower Rhine. The German War of Liberation in 1813, led by Prussia, had been made Infantry Gen Friedrich, Count possible by Prussia’s persuading of Russia to continue its advance into Kleist von Nollendorf was the Central Europe after driving the wreckage of Napoleon’s Grande Armée original commander, but was replaced with the 72-year-old back into Poland. -

Février Août 2019

À PARAÎTRE EN NORMANDIE Toutes les nouveautés éditoriales en Normandie FÉVRIER » AOÛT 2019 PDF interactif Sommaire Index Page - Page + Clic Mail Site internet À PARAÎTRE EN NORMANDIE Toutes les nouveautés éditoriales en Normandie FÉVRIER » AOÛT 2019 NL&L fédère l’ensemble des acteurs Art, cinéma & photographie …… du livre et de la lecture en une plateforme 1 interprofessionnelle qui s’articule autour de l’information, la coopération Histoire & patrimoine …… 2 et l’expertise. En concertation avec la DRAC de Normandie et la Région Bande dessinée & Jeunesse …… Normandie, NL&L accompagne 6 la professionnalisation et le développement des maisons Littérature ……10 d’édition et des librairies ; elle soutient l’animation et la création littéraire ; Sciences humaines & vie pratique …… elle contribue au développement 17 des publics et des pratiques de lecture, à la structuration du réseau de lecture Index des éditeurs …… 19 publique et participe à la valorisation du patrimoine écrit dans une logique de conservation partagée et de coopération régionales. les titres accompagnés de cette icône ont bénéficié d’un soutien de la Drac de Normandie et de la Région NL&L organise le festival «Les Boréales, Normandie au titre du FADEL Normandie plateforme de création nordique». ART CINÉ MA& 1 PHO LES COLLECTIONS DU MUSÉE TO DU CHÂTEAU DE FLERS LES PEINTRES AQUOSITÉS À HONFLEUR Collectif - En coédition avec la ville de Flers Kevin Louviot (photographies) Anne-Marie Bergeret Préface de Belinda Cannone GRA Les collections du musée du château de Flers présentent un panorama très varié de la peinture Depuis le début du XIXe siècle, Honfleur accueille Caen vue à travers ses territoires aquatiques, occidentale du XVIe au XXe siècle. -

75E Anniversaire Du Débarquement Et De La Bataille De Normandie À Ouistreham Riva-Bella – 2019

75e anniversaire du Débarquement et de la Bataille de Normandie à Ouistreham Riva-Bella – 2019 1/28 Repères historiques Le Débarquement allié du 6 juin 1944, à Sword Beach - page 3 Quelques figures emblématiques du Débarquement à Sword Beach Léon Gautier, vétéran du Commando Kieffer ayant débarqué le 6 juin 1944 – page 5 Philippe Kieffer, Commandant – page 8 Alexandra Lofi, membre du n°4 Commando, il en a pris le commandement le 6 juin 1944 au soir en remplacement du commandant Kieffer blessé au combat. – page 9 L’histoire des commémorations L’histoire des commémorations du Débarquement à Ouistreham Riva-Bella – page 10 Ouistreham Riva-Bella, ville de la cérémonie internationale du 70e anniversaire du Débarquement – page 14 Le choix du logo pour le 75e – page 16 Les lieux de visite mémorielle à Ouistreham Riva-Bella La Promenade de la Paix – page 17 Le musée du Mur de l’Atlantique – Le Grand Bunker – page 17 Le musée n°4 Commando – page 17 Programme des commémorations et festivités pour le 75e anniversaire du Débarquement à Ouistreham Les commémorations et cérémonies officielles – page 19 Les festivités pour célébrer la Libération – page 20 Nouveauté 2019 : Parcours sonore au cœur de l’histoire des territoires et du vécu des habitants pendant l’Occupation et à la Libération. Réalité augmentée auditive proposée par Caen la mer. – page 23 La ville aux couleurs du 75e : Pavoisement, expositions dans la ville, plantation d’arbres – page 24 Le stationnement gratuit dans la ville le 6 juin – page 25 Les restrictions de circulation établies par la Préfecture du Calvados, le 6 juin 2019 Transports scolaires suspendus la journée du 6 juin 2019 – page 26 La Zone de Circulation Régulée et l’obtention du sticker si nécessaire – page 26 2/28 Ouistreham Riva-Bella a été occupée par les Allemands dès le 19 juin 1940 et du fait de sa position géographique a été fortifiée dès 1941. -

Annex 9: Forces Present on October 29Th, 1812 Combined Russian

Annex 9: Forces present on October 29th, 1812 Combined Russian Army Wittgenstein Vanguard Prince Jachwill (6,760 infantry + 2,050 cavalry + 28 guns) Cavalry Alexseiev Br. ? Rodianov II Cossacks Regiment 260 men Platov # 4 Don Cossack Regiment 270 men Br. ? Grodno Hussar Regiment (8 sq.) 840 men Converged Hussars Regiment (4 Sq.) 450 men Converged Dragoons (3 Sq. from Pskof, Moscou, Kargopol) 230 men Infanterie Harpe Br ? 2nd Jager Regiment (2 Bns.) 950 men 3rd Jager Regiment (2 Bns.) 550 men 1/23rd Jager Regiment 450 men 25th Jager Regiment (2 Bns.) & 2/Kexholm Infantry Regiment 1,050 men Br. ? Mohilev Infantry Regiment (2 Bns.) 820 men (with 6th St. Petersburg Opolochenie) 610 men Navajinsk Infantry Regiment (2 Bns.) 630 men (with 7th St. Petersburg Opolochenie: 600 men) 600 men Podolia Infantry Regiment (2 Bns) 1,100 men Artillery Half Position Battery #14 4-12pdrs & 2 Licornes Light Battery #26 8-6pdrs & 4 Licornes Horse Battery #1 7-6pdrs & 3 Licornes Right Wing under Steinheil (7,795 infantry + 870 cavalry + 28 guns) First Line Sazonov Br. ? 26th Jager Regiment (2 Bns.) 760 men Mittau Dragoons Regiment (4 Sq.) 460 men Br. ? Toula Infantry Regiment (2 Bns.) 620 men (with 3rd St. Petersburg Opolochenie: 470 men) 470 men Tenguinsk Infantry Regiment (2 Bns.) 620 men (with 2nd St. Petersburg Opolochenie: 470 men) 470 men Br. Helfreich Estonia Infantry Regiment (2 Bns.) 630 men (with 8th St. Petersburg Opolochenie: 600 men) 600 men Voronej Infantry Regiment (2 Bns.) 960 men Artillery Position Battery #6) 8-12pdrs & 4 Licornes from Position Battery #28 3-12pdrs & 1 Licorne Second Line Adadourov Br. -

All for the King's Shilling

ALL FOR THE KING’S SHILLING AN ANALYSIS OF THE CAMPAIGN AND COMBAT EXPERIENCES OF THE BRITISH SOLDIER IN THE PENINSULAR WAR, 1808-1814 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Edward James Coss, M.A. The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor John Guilmartin, Adviser _______________________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Adviser Professor John Lynn Graduate Program in History Copyright by Edward J. Coss 2005 ABSTRACT The British soldier of the Peninsular War, 1808-1814, has in the last two centuries acquired a reputation as being a thief, scoundrel, criminal, and undesirable social outcast. Labeled “the scum of the earth” by their commander, the Duke of Wellington, these men were supposedly swept from the streets and jails into the army. Their unmatched success on the battlefield has been attributed to their savage and criminal natures and Wellington’s tactical ability. A detailed investigation, combining heretofore unmined demographic data, primary source accounts, and nutritional analysis, reveals a picture of the British soldier that presents his campaign and combat behaviors in a different light. Most likely an unemployed laborer or textile worker, the soldier enlisted because of economic need. A growing population, the impact of the war, and the transition from hand-made goods to machined products displaced large numbers of workers. Men joined the army in hopes of receiving regular wages and meals. In this they would be sorely disappointed. Enlisted for life, the soldier’s new primary social group became his surrogate family. -

The Austrian Imperial-Royal Army

Enrico Acerbi The Austrian Imperial-Royal Army 1805-1809 Placed on the Napoleon Series: February-September 2010 Oberoesterreicher Regimente: IR 3 - IR 4 - IR 14 - IR 45 - IR 49 - IR 59 - Garnison - Inner Oesterreicher Regiment IR 43 Inner Oersterreicher Regiment IR 13 - IR 16 - IR 26 - IR 27 - IR 43 Mahren un Schlesische Regiment IR 1 - IR 7 - IR 8 - IR 10 Mahren und Schlesischge Regiment IR 12 - IR 15 - IR 20 - IR 22 Mahren und Schlesische Regiment IR 29 - IR 40 - IR 56 - IR 57 Galician Regiments IR 9 - IR 23 - IR 24 - IR 30 Galician Regiments IR 38 - IR 41 - IR 44 - IR 46 Galician Regiments IR 50 - IR 55 - IR 58 - IR 63 Bohmisches IR 11 - IR 54 - IR 21 - IR 28 Bohmisches IR 17 - IR 18 - IR 36 - IR 42 Bohmisches IR 35 - IR 25 - IR 47 Austrian Cavalry - Cuirassiers in 1809 Dragoner - Chevauxlégers 1809 K.K. Stabs-Dragoner abteilungen, 1-5 DR, 1-6 Chevauxlégers Vienna Buergerkorps The Austrian Imperial-Royal Army (Kaiserliche-Königliche Heer) 1805 – 1809: Introduction By Enrico Acerbi The following table explains why the year 1809 (Anno Neun in Austria) was chosen in order to present one of the most powerful armies of the Napoleonic Era. In that disgraceful year (for Austria) the Habsburg Empire launched a campaign with the greatest military contingent, of about 630.000 men. This powerful army, however, was stopped by one of the more brilliant and hazardous campaign of Napoléon, was battered and weakened till the following years. Year Emperor Event Contingent (men) 1650 Thirty Years War 150000 1673 60000 Leopold I 1690 97000 1706 Joseph -

Dossier De Presse

© Michel Dehaye – A vue d’oiseau - Dossier de presse - Novembre 2018 Ville de Ouistreham Riva-Bella - Dossier de presse – Novembre 2018 – Page 1/33 ituée sur le littoral normand, à 2 h de Paris par l’autoroute et à moins de 10 minutes de Caen par S la voie express, Ouistreham Riva-Bella jouit d’une position géographique avantageuse. Son port multi-fonctions fait d’elle une ville incontournable du Calvados : elle offre à Caen et à toute sa région l’ouverture sur la mer qui dope ses échanges commerciaux. Sommaire Pages 3 à 12 : Le caractère maritime de la ville a déterminé son histoire, son nom Page 3 : Fiche d’identité de la ville - A l’origine même, un village de pêcheurs Page 4 : Histoire de la redoute – Page 5 : Histoire du canal de Caen à Ouistreham Riva-Bella Pages 6 et 7 : Ouistreham Riva-Bella, au temps des bains de mer Pages 8 à 10 : Sword Beach – Débarquement Allié du 6 juin 1944 Pages 11 et 12 : Ouistreham Riva-Bella, ville de la cérémonie internationale du 70e anniversaire du Débarquement Page 13 : Un projet de musée franco-britannique Page 13 : Un appel aux dons pour une promenade de la paix Pages 14 à 20 : Le port de Caen-Ouistreham, 10e port de France Pages 14 et 15 : Un port de commerce et un port de tourisme transmanche avec le ferry Pages 15 et 16 : Le développement du tourisme de croisières et la création du club « Caen- Ouistreham Normandy Cruise » Pages 17 et 18 : Le port de plaisance et la halle aux poissons Pages 19et 20 : Bientôt une 5e fonction pour le port, l’éolien – dans l’attente, le réaménagement de l’avant-port