The Prusso-Saxon Army and the Battles of Jena and Auerst&Dt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourismuskonzept Für Das Weimarer Land Pdf, 2139 Kb

Konzept Weimarer Land Tourismus 2017-2025 Weimarer Land Tourismus Begleitende Tourismus-Agenturen: Bahnhofstraße 28 99510 Apolda NeumannConsult [email protected] Büro Münster www.weimarer-land-tourismus.de Alter Steinweg 22-24 48143 Münster [email protected] Kontakt: Katy Kasten-Wutzler Büro Erfurt [email protected] Juri-Gagarin-Ring 152 Tel: 03644 519975 99084 Erfurt [email protected] Landratsamt Weimarer Land Amt für Wirtschaftsförderung und Kulturpflege Kontakt: Bahnhofstraße 28 Prof. Dr. Peter Neumann 99510 Apolda Tel. 02 51 / 48 286 - 33 Fax 02 51 / 48 286 - 34 Kontakt: E-Mail [email protected] Matthias Ameis www.neumann-consult.com [email protected] Tel: 03644 540221 Project M GmbH Tempelhofer Ufer 23/24 10963 Berlin Tel. 030.21 45 87 0 Fax 030.21 45 87 11 [email protected] Kontakt: Dipl.-Volksw. Andreas Lorenz Büro Berlin gekürzte Version [email protected] Stand: 06.01.2017 www.projectm.de Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Vorbemerkung – Weimarer Land mitten in Thüringen ............................................................................. 2 2. Die SWOT-Analyse ................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Bestandsanalyse – Stärken und Schwächen ............................................................................................ -

Mitteilungsblatt

AMTLICHES MITTEILUNGSBLATT Amtsblatt der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Bad Tennstedt bestehend aus den Mitgliedsgemeinden: Bad Tennstedt, Ballhausen, Blankenburg, Bruchstedt, Haussömmern, Hornsömmern, Kirchheilingen, Klettstedt, Kutzleben, Mittelsömmern, Sundhausen, Tottleben und Urleben mit öffentlichen Bekanntmachungen der Mitgliedsgemeinden Jahrgang 28 | Nr. 8/2018 Freitag, den 27. April 2018 nächster Redaktionsschluss: Montag, den 30.04.2018 nächster Erscheinungstermin: Freitag, den 11.05.2018 Aus dem Inhalt Amtliche Bekanntmachungen - VG Bad Tennstedt - Bad Tennstedt - Sundhausen Veranstaltungen in der Ver- waltungsgemeinschaft - Maifeuer in Haussömmern - Maifeuer in Tottleben - 7. Crosslauf für Kinder in Sundhausen - „Anwassern“ im Kurpark Bad Tennstedt - Vogelstimmenwanderung in Mittelsömmern - Frühlingskonzert des Stad- torchesters Bad Tennstedt - Bücherzwerge in der Bib- liothek - Kurkonzerte in Bad Tennstedt - Release Party im Kosmo- laut Gemeindenachrichten - Frühjahrsputz in Bad Tennstedt - Danksagung an Jagdgenos- senschaft Haussömmern - Kita Kirchheilingen- Ein spannendes letztes Kinder- gartenjahr - Geburtstage im Mai Schulnachrichten - 1. Elternversammlung für die zukünftigen 1. Klassen der Sebastian- Kneipp-Grundschule Bad Tennstedt - Der Geografie-Wettbewer- bes Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Gymnasiums - Die Pressekonferenz der Novalis-Regelschule - Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn- Gymnasium hat hinter die Kulissen des KiKA geschaut - Ferienrückblick der THEPRA Grundschule Kirchheilingen Redaktionsschluss - Vorlesewettbewerb am für das nächste -

A Genealogical Handbook of German Research

Family History Library • 35 North West Temple Street • Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3400 USA A GENEALOGICAL HANDBOOK OF GERMAN RESEARCH REVISED EDITION 1980 By Larry O. Jensen P.O. Box 441 PLEASANT GROVE, UTAH 84062 Copyright © 1996, by Larry O. Jensen All rights reserved. No part of this work may be translated or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the author. Printed in the U.S.A. INTRODUCTION There are many different aspects of German research that could and maybe should be covered; but it is not the intention of this book even to try to cover the majority of these. Too often when genealogical texts are written on German research, the tendency has been to generalize. Because of the historical, political, and environmental background of this country, that is one thing that should not be done. In Germany the records vary as far as types, time period, contents, and use from one kingdom to the next and even between areas within the same kingdom. In addition to the variation in record types there are also research problems concerning the use of different calendars and naming practices that also vary from area to area. Before one can successfully begin doing research in Germany there are certain things that he must know. There are certain references, problems and procedures that will affect how one does research regardless of the area in Germany where he intends to do research. The purpose of this book is to set forth those things that a person must know and do to succeed in his Germanic research, whether he is just beginning or whether he is advanced. -

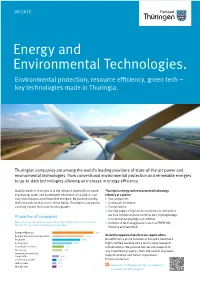

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets the Tower Was the Seat of Royal

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets The Tower was the seat of Royal power, in addition to being the Sovereign’s oldest palace, it was the holding prison for competitors and threats, and the custodian of the Sovereign’s monopoly of armed force until the consolidation of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in 1805. As such, the Tower Hamlets’ traditional provision of its citizens as a loyal garrison to the Tower was strategically significant, as its possession and protection influenced national history. Possession of the Tower conserved a foothold in the capital, even for a sovereign who had lost control of the City or Westminster. As such, the loyalty of the Constable and his garrison throughout the medieval, Tudor and Stuart eras was critical to a sovereign’s (and from 1642 to 1660, Parliament’s) power-base. The ancient Ossulstone Hundred of the County of Middlesex was that bordering the City to the north and east. With the expansion of the City in the later Medieval period, Ossulstone was divided into four divisions; the Tower Division, also known as Tower Hamlets. The Tower Hamlets were the military jurisdiction of the Constable of the Tower, separate from the lieutenancy powers of the remainder of Middlesex. Accordingly, the Tower Hamlets were sometimes referred to as a county-within-a-county. The Constable, with the ex- officio appointment of Lord Lieutenant of Tower Hamlets, held the right to call upon citizens of the Tower Hamlets to fulfil garrison guard duty at the Tower. Early references of the unique responsibility of the Tower Hamlets during the reign of Bloody Mary show that in 1554 the Privy Council ordered Sir Richard Southwell and Sir Arthur Darcye to muster the men of the Tower Hamlets "whiche owe their service to the Towre, and to give commaundement that they may be in aredynes for the defence of the same”1. -

Bad Mergentheim Deutschordensmuseum Aub

| 2 Aub Fränkisches Spitalmuseum 97239 Aub, Von den mittelalterlichen Hauptstraße 29-33 Wurzeln bis zum aktuellen 09335/ 997426 od. 97100 Hospizgedanken prä sentiert þ www.spitalmuseum.de das ehemalige Pfründner- Apr. - Okt., spital auf 500 m2 Leben, Fr., Sa., So. 13–17 Uhr Arbeiten und Wohnen im und nach Vereinbarung Schutz gebauter Caritas mit Wohn- und Krankenstuben, Spitalarchiv, Wirtschaftshof und vollständigem neugoti- schen Kirchenraum. Bad Mergentheim Deutschordensmuseum 97980 Bad Mergentheim, Neue Abteilung ab Mai 2015: Schloß 16 Jungsteinzeit im Taubertal. 07931/52212; Fax 52669 Das Schloss von Mergentheim þ www.deutschordens war 1525-1809 Residenz der museum.de Hoch- und Deutschmeister @ info@ des Deutschen Ordens. Auf deutschordensmuseum.de rund 3000 m2 wird neben der -------------------------------- großen Abteilung „Geschichte Apr. - Okt.: Di.-So. u. Feier- des Deutschen Ordens“ mit tage 10.30-17 Uhr; den fürstlichen Wohnräumen Nov. - März: Di.- Sa. 14-17 die Geschichte Mergentheims Uhr, Sonn- und Feiertage mit Engel-Apotheke und 10.30-17 Uhr. Adelsheim-Sammlung präsentiert. Das Mörike- Öffentl. Führungen: Kabinett erinnert an den Aufenthalt des Dich- Sa., So.,+ Feiert. 15 Uhr. ters in der Stadt (1844-51). 40 Puppenküchen, Führungen f. Kurgäste -stuben und -häuser und Kaufläden (19./20. Do., 15.30 Uhr (Apr.-Okt.) Jhd.) berichten vom Leben vergangener Zeiten. Führungen für Gruppen Es finden Sonderausstellungen, Vorträge, Lesun- und Schulklassen nach gen, Konzerte und museumspädagogische Akti- Vereinbarung. vitäten statt. Bad Mergentheim Führungskultur rund um den Trillberg - einst und jetzt 97980 Bad Mergentheim Unter dem The- Drillberg ma „Führungs- 07931/91-0 kultur rund um Fax 07931-91-4022 dem Trillberg – þ www.wuerth-industrie. einst und jetzt“ com folgen Sie einem @ museum@wuerth- Gang durch die industrie.com 800-jährige Ge- Auf Anfrage schichte unserer Region in ihrer Einbindung in den Zusammenhang der europäischen Geschich- Museen Schlösser Sehenswürdigkeiten 3 te. -

Stadtverwaltung Blankenhain, Marktstraße 4, 99444 Blankenhain Sachgebiet Bauamt / Liegenschaften

Stadtverwaltung Blankenhain, Marktstraße 4, 99444 Blankenhain Sachgebiet Bauamt / Liegenschaften Ansprechpartner: Frau Herr Annett Weise Christian Kerner Telefon Telefon 036459/440-25 036459/440-19 E-Mail E-Mail [email protected] [email protected] Mobil 0162/530 18 57 Fax 036459/440-17 Gliederung Seite Lage des Schlosses, Anfahrt 3 Räume im Erdgeschoss Küche 4 Vereinszimmer 5 Saal 6 Freizeittreff 7 Räume im Obergeschoss Trauzimmer 8 Saal 9 Raum Setup 10 Außenanlagen Innenhof 11 Schlossvorplatz 12 Hochzeit / Standesamt / Führung 13 Lagepläne – Erdgeschoss 14 Lagepläne – Obergeschoss 15 Lagepläne – Außenanlage 16 Benutzungsordnung / Entgeltordnung / Antrag Raumnutzung / Jahreskalender 17 Impressum Lage des Schlosses, Anfahrt Die Lindenstadt Blankenhain liegt in etwa 350 Meter Höhe in der Talsenke der Schwarza, die die Stadt von Ost nach West durchfließt. Nördlich liegt der 497 Meter hohe Kaitsch und westlich erheben sich ebenfalls bewaldete Berge, die zur geologischen Formation der Ilm- Saale-Platte (Muschelkalk) gehören. Nach Süden und Osten erstreckt sich eine wellige Hochfläche, auf der die meisten Ortsteile Blankenhains liegen. Das um 1150 erbaute Schloss Blankenhain/Thür. geht auf eine romanische Ringhausburg zurück. Die Form eines geschlossenen, unregelmäßigen Ovals verleiht dem Schloss architektonischen Seltenheitswert. In den vergangenen Jahren wurde das Schloss umfangreich saniert und es präsentiert sich in einem neuen ansprechenden Ambiente. Die neu geschaffenen sowie die rustikalen Räume eigenen sich für Familienfeiern, Tagungen und Events. Unsere Adresse: Am Markt 2, 99444 Blankenhain/Thür Schloss Blankenhain Anfahrt über die Autobahn A4 Aus Richtung Erfurt kommend, fahren Sie an der Abfahrt Nohra / Bad Berka / Weimar West von der Autobahn ab, um dann auf der B85 über Bad Berka nach Blankenhain zu gelangen. -

Übersicht Der Philharmonischen Sommerkonzerte an Besonderen Orten

Übersicht der Philharmonischen Sommerkonzerte an besonderen Orten 25.06.2021 , 18 Uhr EISENACH in der Georgenkirche Eröffnungskonzert der Telemann-Tage „Zart gezupft und frisch gestrichen“ von Telemann zum jungen Mozart, mit der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach, Solovioline/Leitung Alexej Barchevitch, Solistin Natalia Alencova, Mandoline (Tickets 20,-, erm. 15 Euro, www.telemann-eisenach.de) 27.06., 04.07. und 11.07.2021 jeweils 16 Uhr BAD SALZUNGEN im Garten der Musikschule Bratschenseptett „Ars nova“ der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach Blechbläserquartett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach Bläserquintett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (Eintritt frei, wir freuen uns über Spenden) 02.07.2021 19:30 Uhr EISENACH Landestheater Eisenach Eröffnungskonzert des Sommerfestivals des Landestheaters Eisenach mit dem Bläseroktett, Kontrabass und Schlagwerk der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (www.landestheater-eisenach.de, Touristinfo Eisenach, www.eventim.de) 03.07. und 17.07.2021, 17 Uhr BAD LIEBENSTEIN / SCHLOSSPARK ALTENSTEIN "Hofmusik zur Zeit Georgs I. von Sachsen-Meiningen" mit der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach, Solovioline/Leitung Alexej Barchevitch "Auf die Harmonie gesetzt" - Liebensteiner Bademusik mit dem Bläseroktett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (Tickets über www.ticketshop-thueringen.de) 03.07. – 29.08.2021 SCHLOSSHOF OPEN AIR auf Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha mit verschiedenen Konzertprogrammen u.a. mit den Stargästen Ragna Schirmer und Martin Stadtfeld und vielen weiteren prominenten -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, I MARCH, 1945

Il82 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, i MARCH, 1945 No..' 6100031 (Lance-Sergeant Eric Francis Aubrey No. 6977405 Private Thomas Dawson, The King's Upperton, The Green Howards (Alexandra, Own Scottish Borderers (Kells, Co. Meath). Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment) No. 14244985 Private (acting Corporal) Mathew (High Wycombe). Lawrence Morgan, The Cameromans (Scottish No. 14655457 Lance-Corporal John Wilks, The Green Rifles). Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own No. 5182405 Corporal (acting Sergeant) Albert Victor Yorkshire Regiment) (Scunthorpe). Walker, The Gloucestershire Regiment (Water- No. 58189820 Private Harold Gmntham Birch, The moore, Glos). Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's No. 5258245 Sergeant John Isaac Gue'st, The Own Yorkshire Regiment). Worcestershire Regiment (Worcester). No. 144274180 Private James Alfred Reddington, No. 4982401 Sergeant William Francis Jennings, The The Green Howards (Alexandra, 'Princess of Worcestershire Regiment (London, £.14). Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment) (Deal). No. 5257827 Lance-Corporal Alfred Henry Palmer, No. 5388512 Private Frederick James Riddle, The The Worcestershire Regiment (Redditch). Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's No. 5257681 Private George Bromwich, The ' Own "Yorkshire Regiment) (ChaMont-St.-Giles). Worcestershire Regiment (Rugby). No. 3772811 Sergeant George Bannerman, The Royal No. 5436899 Private Reginald Lugg, The Worcester- Scots Fusiliers (Nottingham). shire Regiment (Reading). No. 3125986 Sergeant Albert Shires, The Royal No. 14419045 Private Arthur Edwin Stacey, The Scots Fusiliers (iHartlepool). Worcestershire Regiment (Shaftesbury). No. 3775276 Corporal (acting Sergeant) William No. 3380*595 Warrant Officer Class I Ernest William Beagan, The Royal Scots Fusiliers (Liverpool 4). Churchill, The East Lancashire Regiment No. 3134048 Corporal (acting Sergeant) William John (tAlnwick). -

La Bataille De Jena 1806© (4 Maps)

La Bataille pour la Prusse 1806 Rev. 1 b 1 /2018 La Bataille de Jena 1806© (4 maps) Battle Two Largely Historical This is the historic battle for Jena, a decisive victory for the French. Therefore, the French player must be equally decisive and keep to an aggressive time table. The Prussians may be out- numbered but their mission is to delay the French for a time, and then withdraw to the next defensive line. Start 8:00 and finish at the end of the 15:40 turn Boundary – All four Jena maps Movement suggestions – with 4 players: 10 minutes for the French and 8 minutes for the Coalition No units may start or enter in Road March. French units rout in the direction toward their entry points. Prussian units rout in the direction of Weimar. Fog Between 8:00 and the end of the 9:20 turn in the morning, conditions include fog. During this time frame: Artillery is limited to medium or short range only Infantry may form Carre in their movement phase, only. Infantry movement is reduced by 2 movement points Artillery movement is reduced by 2 movement points, except on roads in Road March Cavalry and horse artillery movement is reduced by 5 movement points except in Road March Cavalry may not Charge, Reaction Charge, or Opportunity Charge All fire attacks are modified to reflect 2/3 of their normal value Units may always move one if restriction of terrain and fog would not allow them to do so. Jena 1806 Page 1 of 6 Marshal Enterprises La Bataille pour la Prusse 1806 Rev. -

French Army & Mobilized Forces of Client States Dispositions By

French Army & Mobilized Forces of Client States Dispositions By Regiment, Battalion, Squadron, & Company May l8ll Line Infantry Military Division Regt Bn Emplacement or Army Assignment lst l en route Rome 30th Military Division 2 en route Rome 30th Military Division 3 en route Rome 30th Military Division 4 In Toulon 8th Military Division 5 Marseille 8th Military Division 2nd l Delfzyl 3lst Military Division 2 Onderdendam 3lst Military Division 3 Leuwarden 3lst Military Division 4 Upper Catalonia 3rd Div/Army of Catalonia 5 Besancon 6th Military Division 6 forming 3rd l St. Malo l3th Military Division 2 Brest l3th Military Division 3 Brest l3th Military Division 4 Strasbourg 5th Military Division 5 Strasbourg 5th Military Division 4th l Havre l5th Military Division 2 Havre l5th Military Division 3 Dieppe 4th Military Division 4 Nancy 4th Military Division 5 Nancy 4th Military Division 5th l Toulon 8th Miltiary Division 2 Toulon 8th Miltiary Division 3 Barcelona Div/Army of Catalonia 4 Grenoble 7th Military Division 5 Grenoble 7th Military Division 6th l Corfu/Fano Division des 7 Isles 2 Corfu/Fano Division des 7 Isles 3 Rome 30th Miltiary Division 4 Civita-Vecchia 30th Miltiary Division 5 Rome 30th Military Division 6 Corfu/Fano Division des 7 Isles 7 Corfu/Fano Division des 7 Isles 7th l lst Div/Army of Catalonia 2 lst Div/Army of Catalonia 3 lst Div/Army of Catalonia 4 lst Div/Army of Catalonia 5 Turin 27th Military Division 8th l 2nd Div/lst Corps/Army of Spain 2 2nd Div/lst Corps/Army of Spain 3 2nd Div/9th Corps/Army of Spain 4 2nd