Satires, Epistles and Ars Poetica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17Th-First Half of the 18Th Century

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Siedina, Giovanna. 2014. The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13065007 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2014 Giovanna Siedina All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Author: Professor George G. Grabowicz Giovanna Siedina The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century Abstract For the first time, the reception of the poetic legacy of the Latin poet Horace (65 B.C.-8 B.C.) in the poetics courses taught at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy (17th-first half of the 18th century) has become the subject of a wide-ranging research project presented in this dissertation. Quotations from Horace and references to his oeuvre have been divided according to the function they perform in the poetics manuals, the aim of which was to teach pupils how to compose Latin poetry. Three main aspects have been identified: the first consists of theoretical recommendations useful to the would-be poets, which are taken mainly from Horace’s Ars poetica. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace’s Satires Horace’s protestations against adultery in the Satires are usually interpreted as superficial, based not on the morality of the act but on the effort that must be exerted to commit adultery. For instance, in Satire I.2, scholars either argue that he is recommending whatever is easiest in a given situation (Lefèvre 1975), or that he is recommending a “golden mean” between the married Roman woman and the prostitute, which would be a freedwoman and/or a courtesan (Fraenkel 1957). It should be noted that in recent years, however, the latter interpretation has been dismissed as a “red herring” in the poem (Gowers 2012). The aim of this paper is threefold: to link the portrayals of adultery in I.2 and II.7, to show that they are based on a deeper reason than easy access to sex, and to discuss the political implications of this portrayal. Horace argues in Satire I.2 against adultery not only because it is difficult, but also because the pursuit of a married woman emasculates the Roman man, both metaphorically, and, in some cases, literally. Through this emasculation, the poet also calls into question the adulterer’s identity as a Roman. Satire II.7 develops this idea further, focusing especially on the adulterer’s Roman identity. Finally, an analysis of Epode 9 reveals the political uses and implications of the poet’s ideas of adultery and situates them within the larger political moment. Important to this argument is Ronald Syme’s claim that Augustus used his poets to subtly spread his ideology (Syme 1960). -

Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Classical Studies Faculty Publications Classical Studies 2016 Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/classicalstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Damer, Erika Zimmermann. "Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12." Helios 43, no. 1 (2016): 55-85. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 ERIKA ZIMMERMANN DAMER When in Book 1 of his Epistles Horace reflects back upon the beginning of his career in lyric poetry, he celebrates his adaptation of Archilochean iambos to the Latin language. He further states that while he followed the meter and spirit of Archilochus, his own iambi did not follow the matter and attacking words that drove the daughters of Lycambes to commit suicide (Epist. 1.19.23–5, 31).1 The paired erotic invectives, Epodes 8 and 12, however, thematize the poet’s sexual impotence and his disgust dur- ing encounters with a repulsive sexual partner. The tone of these Epodes is unmistakably that of harsh invective, and the virulent targeting of the mulieres’ revolting bodies is precisely in line with an Archilochean poetics that uses sexually-explicit, graphic obscenities as well as animal compari- sons for the sake of a poetic attack. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

The Cult of Glykon of Abonuteichos from Lucian of Samosata to Cognitive Science

Cultural and Religious Studies, June 2020, Vol. 8, No. 6, 357-365 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.06.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Building the Supernatural: The Cult of Glykon of Abonuteichos From Lucian of Samosata to Cognitive Science Guido Migliorati Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Brescia, Italy We can argue that the making and the spread of the cult of Glykon of Abonuteichos can be explained through a cognitivist template. Lucian of Samosata’s Pseudomantis booklet and the material evidence, which testifies to the building and the spread of Glykon’s cult by Alexander of Abonuteichos, belong to a historical context characterized by instability, deadly epidemics and military pressure. It is a historical context, therefore, in which people feel reality with anxiety; one of the reactions is the growing up of the belief in prophylactic and prophetic cults, capable to protecting and forecasting. Since Lucian had pointed out that fear and hope were the forces that dominated the lives of men, just as the same had denounced that Alexander of Abonuteichos was ready to exploit those forces to his advantage, the cult of Glykon could be labeled as a trick. However, cognitive science and specifically the hard-wired brain circuit research may offer an alternative explanation: the interaction between potential risk of low probability, but high impact events (unstoppable irruptions of the Germans, or generalized impotence against the spread of disease) can impact on the hard-wired brain circuit activity capable of keeping social and individual anxiety, implicitly conditioning mentality and behavior of a religious “entrepreneur” and consumers, both concerned about protection and forecasting, fear and hope. -

Snakes on Ancient Coins by Peter E

Snakes on Ancient Coins by Peter E. Lewis An albino reticulated python (Wikimedia Commons). NAKES have always had an aura of In Judaism and Christianity there was needed healing travelled to Epidaurus Smystery and danger about them, and a tendency to see snakes as evil. This from all over the Greek and Roman world. in ancient times people were fascinated was because in the book of Genesis a In his temple Asclepius was shown with by them. It is therefore not surprising snake represents Satan and tempts Eve his hand on the head of a snake, indi - that snakes feature in Greco-Roman to disobey God. But the ancient Greeks cating that it was his agent. ( Figure 4 ) religion and that they appear commonly and Romans had a positive view of On a coin of Epidaurus he is also shown on ancient coins. snakes. They knew that if someone was with his hand on a snake. ( Figure 5 ) The bitten by a snake they could die, but this ruins of the temple can still be seen. meant that snakes had power over life Near the temple there was a building in and death. Moreover they observed that a which the sick slept with snakes. ( Figure snake could shed its skin and in a way be 6) Presumably the snakes were tame reborn. So they had power over renewal and non-poisonous, but the psychological and resurrection. All this meant that effect of sleeping with them must have snakes were not like ordinary creatures: been enormous. No wonder many people they belonged to the supernatural realm. -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires Thesis Advisor: Dr. William Wycislo Spring 2004 Acknowledgments My sincerest thanks go to Dr. Wycislo, without whose time and effort this project would have never have happened. Abstract Juvenal was a satirist who has made his mark on our literature and vernacular ever since his works first gained prominence (Kimball 6). His use of allusion and epic references gave his satires a timeless quality. His satires were more than just social commentary; they were passionate pleas to better his society. Juvenal claimed to give the uncensored truth about the evils that surrounded him (Highet 157). He argued that virtue and vice were replacing one another in the Roman Empire. In order to gain better understanding of his claim, in the following paper, I looked into his moral origins as well as his arguments on virtue and vice before drawing conclusions based on Juvenal, his outlook on society, and his solutions. Before we can understand how Juvenal chose to praise or condemn individuals and circumstances, we need to understand his moral origins. Much of Juvenal's beliefs come from writings on early Rome and long held Roman traditions. I focused on the writings of Livy, Cicero, and Polybius as well as the importance of concepts such as pietas andjides. I also examined the different philosophies that influenced Juvenal. The bulk of the paper deals with virtue and vice replacing one another. This trend is present in three areas: interpersonal relationships, Roman cultural trends, and religious issues. First, Juvenal insisted that a focus on wealth, extravagance, and luxury dissolved the common bonds between citizens (Courtney 231). -

Roman Literature from Its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age

The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I by John Dunlop This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I Author: John Dunlop Release Date: April 1, 2011 [Ebook 35750] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. VOLUME I*** HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE, FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. IN TWO VOLUMES. BY John Dunlop, AUTHOR OF THE HISTORY OF FICTION. ivHistory of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I FROM THE LAST LONDON EDITION. VOL. I. PUBLISHED BY E. LITTELL, CHESTNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA. G. & C. CARVILL, BROADWAY, NEW YORK. 1827 James Kay, Jun. Printer, S. E. Corner of Race & Sixth Streets, Philadelphia. Contents. Preface . ix Etruria . 11 Livius Andronicus . 49 Cneius Nævius . 55 Ennius . 63 Plautus . 108 Cæcilius . 202 Afranius . 204 Luscius Lavinius . 206 Trabea . 209 Terence . 211 Pacuvius . 256 Attius . 262 Satire . 286 Lucilius . 294 Titus Lucretius Carus . 311 Caius Valerius Catullus . 340 Valerius Ædituus . 411 Laberius . 418 Publius Syrus . 423 Index . 453 Transcriber's note . 457 [iii] PREFACE. There are few subjects on which a greater number of laborious volumes have been compiled, than the History and Antiquities of ROME. -

Coriolanus and Fortuna Muliebris Roger D. Woodard

Coriolanus and Fortuna Muliebris Roger D. Woodard Know, Rome, that all alone Marcius did fight Within Corioli gates: where he hath won, With fame, a name to Caius Marcius; these In honour follows Coriolanus. William Shakespeare, Coriolanus Act 2 1. Introduction In recent work, I have argued for a primitive Indo-European mythic tradition of what I have called the dysfunctional warrior – a warrior who, subsequent to combat, is rendered unable to function in the role of protector within his own society.1 The warrior’s dysfunctionality takes two forms: either he is unable after combat to relinquish his warrior rage and turns that rage against his own people; or the warrior isolates himself from society, removing himself to some distant place. In some descendent instantiations of the tradition the warrior shows both responses. The myth is characterized by a structural matrix which consists of the following six elements: (1) initial presentation of the crisis of the warrior; (2) movement across space to a distant locale; (3) confrontation between the warrior and an erotic feminine, typically a body of women who display themselves lewdly or offer themselves sexually to the warrior (figures of fecundity); (4) clairvoyant feminine who facilitates or mediates in this confrontation; (5) application of waters to the warrior; and (6) consequent establishment of societal order coupled often with an inaugural event. These structural features survive intact in most of the attested forms of the tradition, across the Indo-European cultures that provide us with the evidence, though with some structural adjustment at times. I have proposed that the surviving myths reflect a ritual structure of Proto-Indo-European date and that descendent ritual practices can also be identified. -

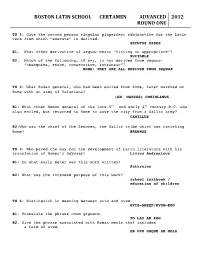

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods.